Metaphysical pathways through the walking dream

Notes after experiencing Laurent Grasso’s exhibition Anima at the Collège des Bernardins in Paris

A well-known quote of the Greek philosopher Heraclitus is “Nature loves to hide”. This can be interpreted literally: for example, mushrooms that only appear above the soil for a very short time and then disappear until the following autumn, or the very brief blooming of St John’s wort (and the only time that it is suitable for picking for herbal tea) before it blends in with the rest of the meadow ecosystem. But this saying can also be interpreted in another way, i.e. we only see that part of reality that we have so far been able to observe/notice/understand with the tools at our disposal. In other words, just because we cannot see something doesn’t mean that is does not exist.

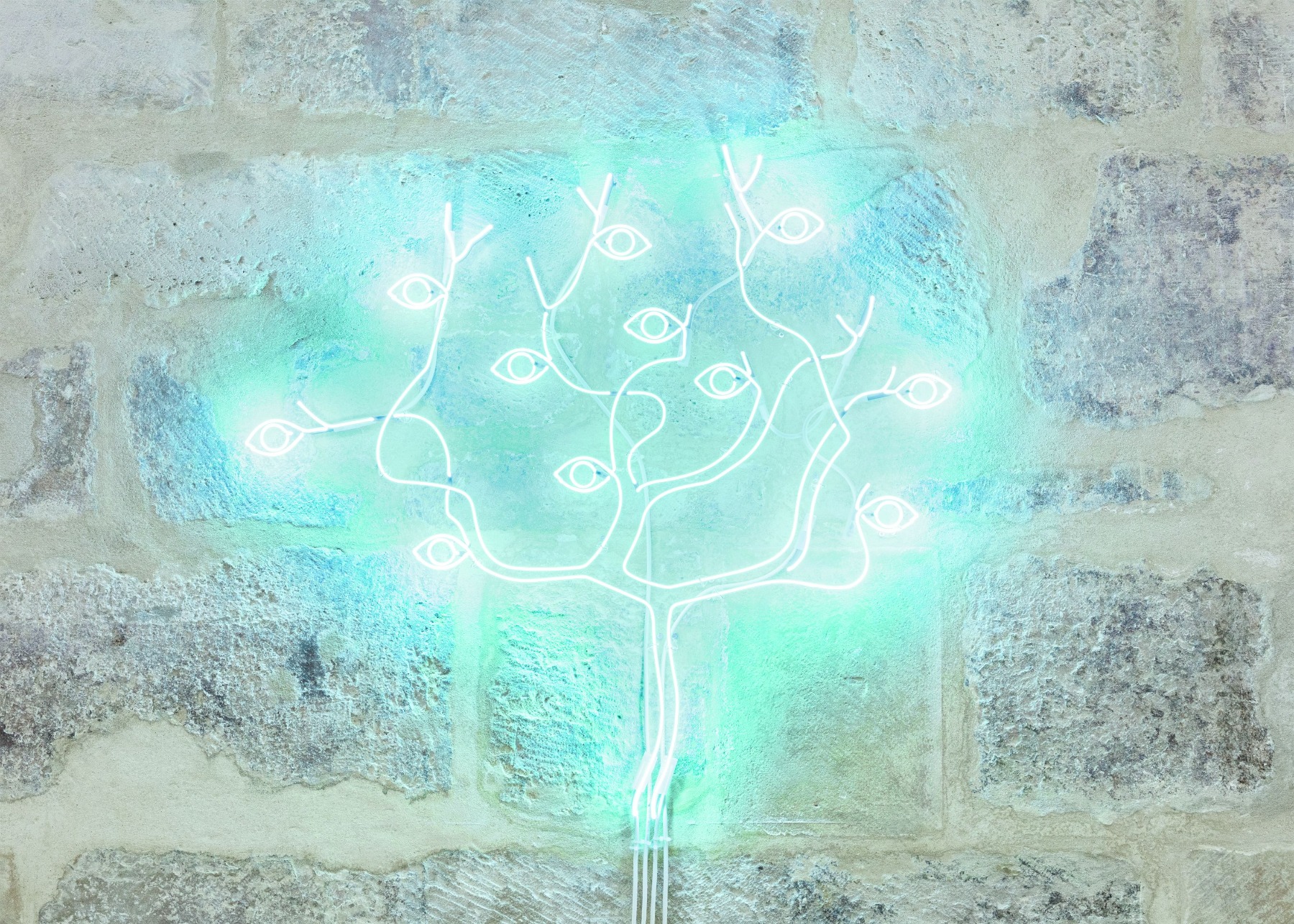

Exhibition view of Anima, Collège des Bernardins, Paris, 2022-2023 / © Laurent Grasso / ADAGP, Paris, 2022 / Photo: Tanguy Beurdeley /

Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin

Nature and the universe as a whole have their own mysteries, and this is the territory in which French artist Laurent Grasso works – without judgement and with the distance of an observer. Without pretending to reveal new truths that might later turn out to be mere conjecture but rather by allowing us to experience being present, he opens the veil to ever new layers of reality by offering an expanded and varied point of view from which to look at things, processes and phenomena – the preconceived notions of which have been shaped by our habitual assumptions, fragmentary private experiences, and, sometimes, inaccurate or even deliberately distorted information. His works, as well as the paths of consciousness that their experiences lead to, are implicitly reminiscent of Socrates’ legendary saying: “I know that I know nothing”.

Exhibition view of Anima, Collège des Bernardins, Paris, 2022-2023 / © Laurent Grasso / ADAGP, Paris, 2022 / Photo: Tanguy Beurdeley /

Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin

Grasso is interested in physics, philosophy, alchemy, anthropology, science fiction and paranormal phenomena as well as various conspiracy theories and their shared margins with reality. Through his work, he constantly pushes himself and the viewer outside the frame of one’s usual experience. And this is also what Anima is – a visually sensory journey between the visible and the invisible, on show through February 18 at Paris’s Collège des Bernardins, a 13th-century Cistercian monastic college that was transformed into a cultural space in 2008.

Exhibition view of Anima, Collège des Bernardins, Paris, 2022-2023 / © Laurent Grasso / ADAGP, Paris, 2022 / Photo: Tanguy Beurdeley /

Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin

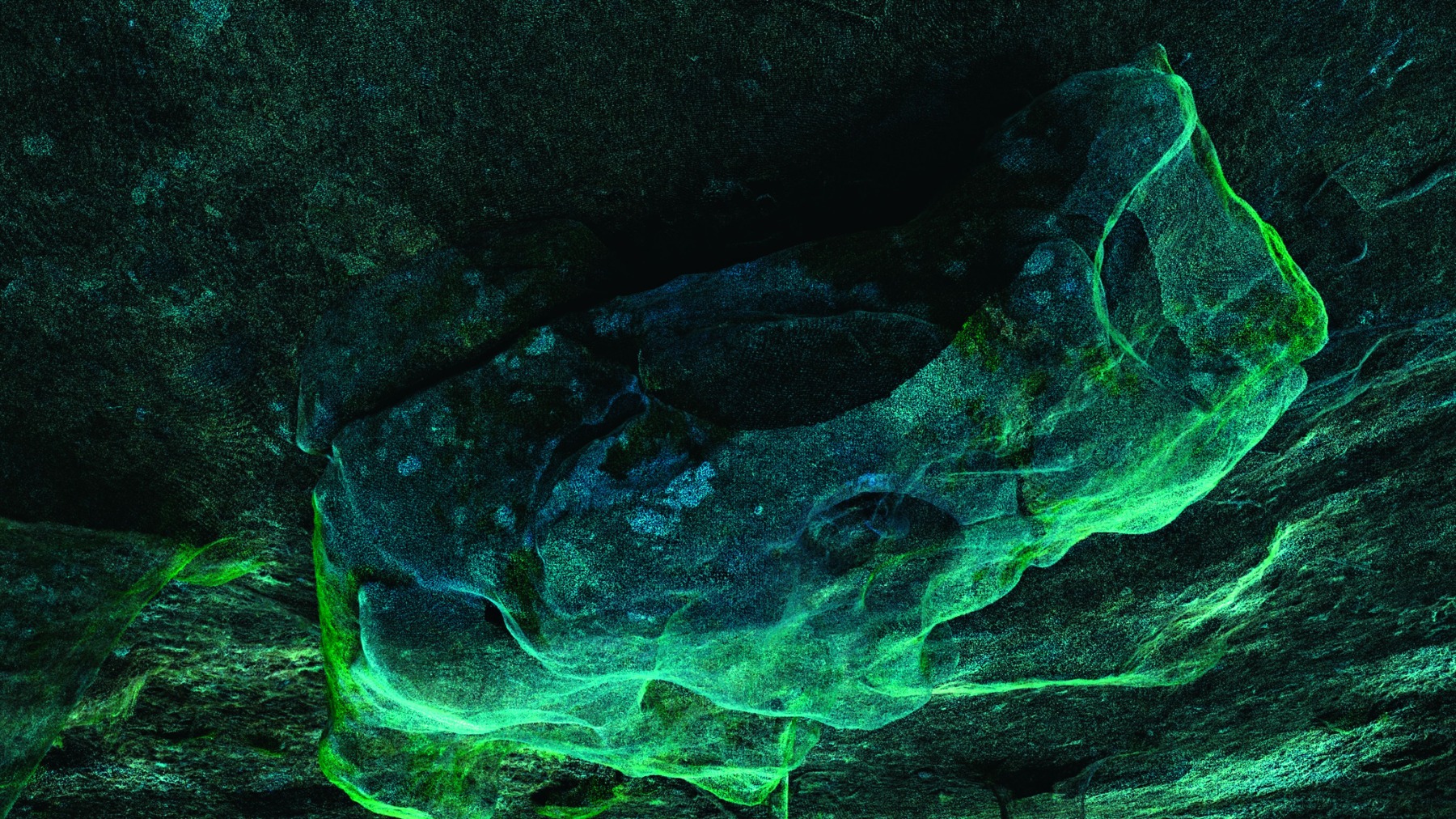

Using as a metaphor/portal an ancient construction shrouded in mystery, the Pagan Wall in the forests of Alsace, Anima takes the viewer into a territory of expanded consciousness in which the line between the physical and the metaphysical is blurred. Encircling Mont Sainte Odile and made of around 300 000 stone blocks, the almost 10-kilometres-long and in some places three-metres-high and two-metres wide wall is thought to have been built by the Celts. At that time, the mountain was known as Altitona (“the high mountain”), and was already considered a sacred place. The Celts built a fortress there, the historic wall of which is now known as the Pagan Wall. In the 7th century, the area was ruled by Etichon, the Duke of Alsace, who, according to legend, abandoned his newborn daughter (who would later be known as Saint Odile) because she was born blind. At the age of twelve, the girl miraculously regained her sight; eventually a convent was built on the site and it became a place of pilgrimage – especially for people with eye diseases.

Exhibition view of Anima, Collège des Bernardins, Paris, 2022-2023 / © Laurent Grasso / ADAGP, Paris, 2022 / Photo: Tanguy Beurdeley /

Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin

The Pagan Wall is surrounded by various mythical stories. This sense of mystery was strengthened by relatively recent events – on January 20, 1992, an Air Inter passenger plane crashed in this area during a local flight from Lyon to Strasbourg. The flight took place at night, in bad weather, and the plane crashed into a dense forest slope, killing 87 people. The nine survivors huddled together in the cold darkness trying to keep each other alive until rescuers arrived.

Exhibition view of Anima, Collège des Bernardins, Paris, 2022-2023 / © Laurent Grasso / ADAGP, Paris, 2022 / Photo: Tanguy Beurdeley /

Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin

Exhibition view of Anima, Collège des Bernardins, Paris, 2022-2023 / © Laurent Grasso / ADAGP, Paris, 2022 / Photo: Tanguy Beurdeley /

Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin

Grasso’s work is also very personal, for the artist spent his childhood in this area. In a sense, he provokes us to enter his enchanted territory with openness and a curiosity that is capable of noticing the smallest of details – a characteristic of young children who are just beginning to explore the world around them. The first thing that the viewer who enters the exhibition at Collège des Bernardins encounters is a series of oil paintings attached to the Gothic columns of the college. Entitled Studies into the Past, the series was inspired by the historical interiors of 17th-century Holland as well as the funerary hatchments placed on the pillars of churches. A stark difference in Grasso’s paintings, however, is that in the seemingly realistic interiors, at about the height of a human, there’s either a silver-gray cloud floating in place or small surreal flames “hang” in the air as if they were light bulbs hung from the domed ceiling; associations can be drawn with both computer simulations and transcendental experience. Inevitably, the Netflix series The Witcher comes to mind – one can imagine the cloud becoming a screen on which appear scenes from ancient legends and the present but invisible world around us.

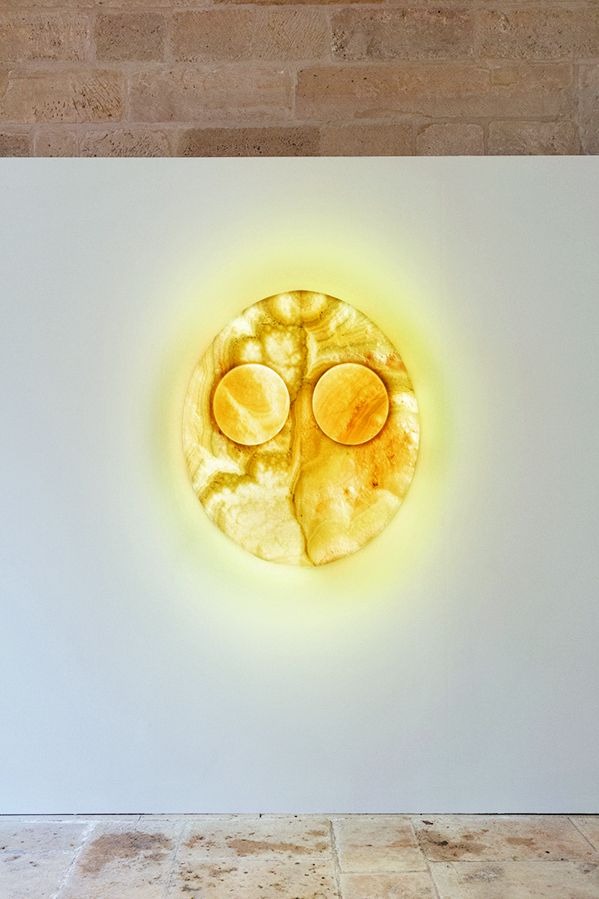

Laurent Grasso, The Schumann Spheres, 2018

Glass, gold and brass spheres, frequency generator, enameled copper wire / Exhibition view of Anima, Collège des Bernardins, Paris, 2022-2023 / © Laurent Grasso / ADAGP, Paris, 2022 / Photo: Tanguy Beurdeley /

Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin

Opposite some of the paintings hang meteorite-like artificial stones in which – like futuristic minerals – small red lights swirl. Consequently, the paintings and the objects connected to them become portals of sorts – between the past and the future, between ancient knowledge that has disappeared and modern technology that seeks to access it or at least record its existence. This is also symbolically evoked by the glass, brass and gold spheres shaped like generators of “Schumann resonances” – ultra-low frequencies circulating between the surface of the Earth and the ionosphere, and which could coincide with those of the human brain.

Every detail/object in the exhibition has a meaning. It is like a metaphysical cognitive puzzle that hypnotically draws the viewer into a story that, by using Grasso’s clues, the viewer puts together themself. The viewer’s steps gradually adapt to the rhythm of the story, becoming silent and slow, eager to notice, to feel, to experience, unconsciously trying not to disturb with any involuntary rapid movement or noise the web of sensations and information swirling in the space. Lingering in the atmosphere conjured by paintings, objects and the ancient college’s patina, a calm gradually settles upon the viewer; the viewer opens up to the mystical forest, ready to enter it.

Exhibition view of Anima, Collège des Bernardins, Paris, 2022-2023 / © Laurent Grasso / ADAGP, Paris, 2022 / Photo: Tanguy Beurdeley /

Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin

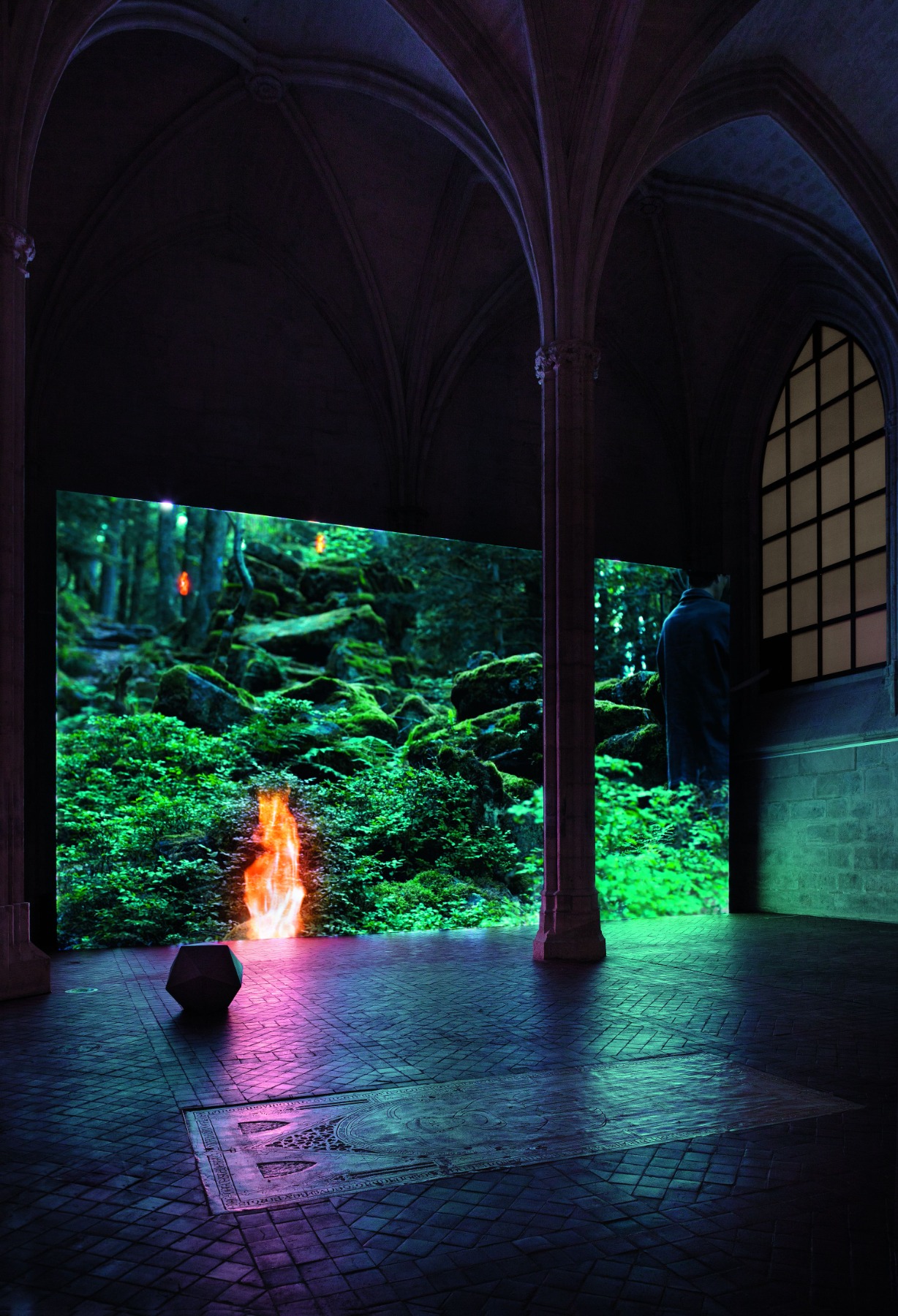

The central axis of the exhibition is the film Anima (18 min, 14 sec), a metaphysical experience in the “forest” of expanded consciousness – something like a conscious dream that transcends time and space and the limits of self-knowledge. Anima simultaneously embodies physical as well as dreamed reality, a territory in which both are present in synchronous unity. In a slowly gliding procession, here the spirit world coexists with artificial intelligence; moss-covered stones and centuries-old trees coexist with the verdant brightness characteristic of the visionary (and also digital) world; and physical beings coexist with artefacts belonging to the 21st century. Glass tubes from a futuristic scientific laboratory seemingly allow the breath of the earth to escape into the atmosphere; a brass divining rod spins in an unknown hand; every once in a while an incredibly beautiful fox runs across the screen; tongues of flame flicker in the air; the same silvery cloud that appears in the paintings floats low among the trees while a mythical wizard/shaman/man walks between these worlds. As the exhibition description says: “Anima generates an ecosystem in which limits – between the living and the inanimate, the visible and the invisible, the human and the non-human – are blurred.”

Exhibition view of Anima, Collège des Bernardins, Paris, 2022-2023 / © Laurent Grasso / ADAGP, Paris, 2022 / Photo: Tanguy Beurdeley /

Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin

The film is projected onto the far wall of the college’s historic sacristy; there are no pews, and the viewer can stand freely or lean against one of the stone columns. In a way, this is also the ideal way to view the work – by allowing oneself to be drawn into the mystical forest; the viewer becomes part of a procession in constant motion – the viewer both experiences and observes at the same time. Although the viewer is physically standing on the stone floor of the college and not in the spongy moss of a forest – and one is fully aware of this – there is a sense that one is at some strange intersection of realities and is moving along in short bursts and taking in the same breath as the fox as it leaps over a moss-covered boulder and then the trunk of a centuries-old fallen tree. Flashes of thoughts and visions beguilingly blur the boundaries between the viewer and the work, bringing the two together to the point of feeling as if one is entering the landscape. In synchrony with the flow of the film’s narrative, the viewer travels deeper and deeper into the forest, and as long as they are in motion, they have the opportunity to observe, experience and learn.

As British anthropologist Tim Ingold writes in his essay Footprints through the weather-world: walking, breathing, knowing: “[…] the mind is not bounded by the body but extends along the multiple sensory pathways that bind every living being into the texture of the world. These pathways, as we have seen, are both traced on the ground as tangible tracks and threaded through the air as trails of scent. Walking along, then, is not the behavioural output of a mind encased within a pedestrian body. It is rather, in itself, a way of thinking and knowing – ‘an activity that takes place through the heart and mind as much as through the feet’ (Rendell). Like the dancer, the walker is thinking in movement.”

Although the mind – which has a nasty habit of trying to explain, conceptualise and direct everything – whispers in the ear that, even though it theoretically takes place in and was filmed in the area around Mont Sainte-Odile, everything on the screen is fiction, a masterpiece of digital technology. Anima allows the mind to go silent for a moment and transcend rationality...to experience a moment of being outside of both a framework and time. Yet, to each his own, because we each experience this world in a completely different way. As does Laurent Grasso. Arterritory presents the following short conversation with the artist.

What did you learn about yourself while working on Anima? Did the time you spent in the Vosges Mountains bring out any previously unconscious or unnoticed aspects of yourself?

The idea of the film was to work on a new way of seeing the world, one in which the human, the non-human, the living, the non-living, the animal and the vegetable are put on the same level and go beyond the usual categories. It is becoming more and more accepted and customary to attribute an “interiority” to them. This “New World”, or rather this new point of view of the world, is made possible both by a sensitive experience and by new theories that deconstruct our old relationship to the world, such as those being developed today by Eduardo Kohn, Philippe Descola and Bruno Latour.

As far as I am concerned, I have always built my projects starting from a sensitive experience and my own questioning, even if I discover later that certain theories were in line with what I was experiencing. For example, when I film sacred aboriginal sites, I realise that their environment, the land and the relief are as much a part of their community as human beings, which is in line with research being carried out by certain anthropologists, yet this is something I discover by experimenting.

For Anima, it was while moving around the forest of Mont Sainte-Odile that I felt like doing the project because I found that the light, the smells, and the presence of trees and certain rocks formed a very interesting ecosystem that produced a certain effect. It is a place that is entwined with various stories that are all very interesting and very heterogeneous: the story of St. Odilia who regained her vision, the plane crash that took place, the supposed presence of cosmo-telluric energies, and the many geobiologists who come to experience the place with measuring instruments...and even certain rites that are still practiced in these places. The presence of the Pagan Wall reinforced these impressions as well as all the beliefs and mythologies around its construction. The shooting was very intense – it rained a lot, the access points to the places I had chosen were quite far away, and we had to carry all the equipment by foot. When the light was soft, the forest was a very peaceful place, but in the rain it became a hostile environment. The monastery where we slept also gave off very unpleasant feelings for me.

What is the mystical experience, and why is it important for us to have it? And why through art, specifically?

Personally, I would say that my work is more related to the immaterial, the invisible, and to metaphysical research. The word mystical is a bit too strong and too connotative for me. Today, beliefs and ideologies have been replaced by scientific theories that allow us to see the world differently and nourish our imagination and our hope. The fictional and narrative potential of certain theories is much stronger than certain stories linked to religious beliefs. Scientific research, such as string theory, quantum physics, and the discovery of solar winds, are producing new imaginations. In addition, there are other less scientific areas that I like to explore because they are pre-scientific in the sense that they are more intuitive but possibly in the process of being rationalised. The use of the 7.83 Hz frequency, discovered by Winfried Otto Schumann, as well as some applications of geobiology in agriculture, are interesting to observe.

Exhibition view of Anima, Collège des Bernardins, Paris, 2022-2023 / © Laurent Grasso / ADAGP, Paris, 2022 / Photo: Tanguy Beurdeley /

Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin

Exhibition view of Anima, Collège des Bernardins, Paris, 2022-2023 / © Laurent Grasso / ADAGP, Paris, 2022 / Photo: Tanguy Beurdeley /

Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin

The devices in my exhibitions (without going towards a mystical experience) produce a certain effect on the spectator. A questioning that nourishes them and extracts them from their temporality, that plunges them into a form of modification of the consciousness, into a kind of waking dream (as can happen to us all in front of a film or in front of a spectacle)...this constitutes the type of experience that I try to create. It is up to each person to describe this experience in the way that best suits them. My installations are open systems that are not clear but rather complex, and in which I try to produce an effect by using all available parameters: the lighting, the architecture, the sound, the frequencies generated by certain works that I install. For example, the Schumann Spheres are spheres with a circuit board that broadcasts a frequency of 7.83 Hz into the exhibition space of Anima.

Laurent Grasso, The Schumann Spheres, 2018

Glass, gold and brass spheres, frequency generator, enameled copper wire / Exhibition view of Anima, Collège des Bernardins, Paris, 2022-2023 / © Laurent Grasso / ADAGP, Paris, 2022 / Photo: Tanguy Beurdeley /

Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin

When a visitor enters the exhibition, they first encounter your oil paintings on wood. They are attached to Gothic columns as if they were portals. Why did you choose wood as the background surface, and what is the role of painting as a medium in this elusive universal dance between the visible and the invisible?

When you enter the Collège des Bernardins, the first thing you see is a forest of columns. These columns go down deep into the earth. They are themselves like transmitters of an earthly force. When I was doing research, I found some Flemish paintings of imaginary church architecture and interiors. What I thought to be paintings were in fact heraldic inscriptions that signify the presence of graves at the foot of the columns. I then decided to develop a custom-made hanging system on the columns of the nave of the College.

Even though these paintings look like they come from the past, the project is more about time travel. There is something futuristic, like a time machine, in this corridor formed by these columns. It’s a time corridor with this forest of columns that prolongs itself with the trees of the forest that we see in the film at the end of this perspective.

The Studies into the Past series is a form of time travel in itself that uses information from my films. The elements we see in the films are projected into other realities, into other times. I like to create lines between the future and history. These lines are expressed in a physical way in this exhibition by starting from the past and ending in the future with the film and this new way of looking at the world. The very historical setting of the College’s nave, as well as the Pagan Wall of Mont Sainte-Odile, are part of a relationship that crosses science fiction and archaeology. My vision of the object and the architecture is part of an approach that projects a memory, an interiority, and a possible influence beyond the object.

Exhibition view of Anima, Collège des Bernardins, Paris, 2022-2023 / © Laurent Grasso / ADAGP, Paris, 2022 / Photo: Tanguy Beurdeley /

Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin