«This festival was born out of impossibility»

A conversation with the curator of the 11th edition of the Survival Kit festival Katia Krupennikova

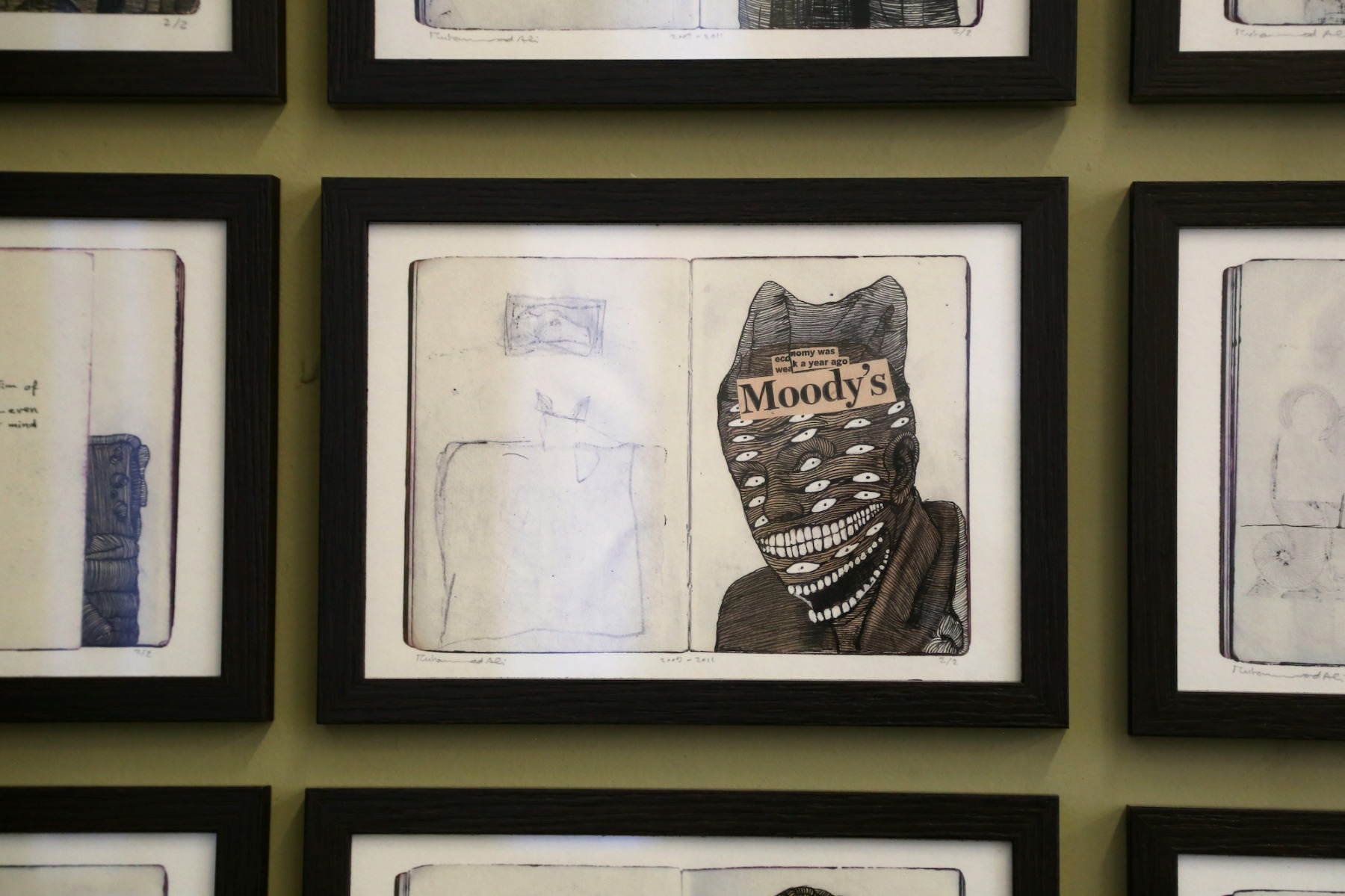

I enter a building on Tērbatas Street, not far from Matīsa Market and what once was the Palace of Sports and has for the last 12 years been a fenced site with a growth of young trees. You can see it quite well from the top floor of the building that used to house the Museum of Literature and Music. Today, this is the epicentre of busy work on the 11th edition of the Survival Kit festival of contemporary art, the creation of the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art. On the second floor of the building, I find myself in a room where a tall young woman in jeans, sneakers and a white t-shirt that says Sorrow Conquers Happiness is trying to figure out the best way of hanging the works of Muhammad Ali, a Syrian refugee artist based in Sweden. It is a series of drawings on newspaper cuttings.

The woman’s name is Katia Krupennikova, and it seems that she has to tear herself away from the organising to start our interview. ‘What? Is it really already five p.m.? Really?’ But then she surrenders herself to the conversation genuinely and unconditionally with the same intensity ‒ just like she had been focusing on the installation of the exhibition before.

Katia Krupennikova at the Sigrid Viir exposition. Photo: Sergejs Timofejevs

Katia Krupennikova is the curator of the 11th Survival Kit festival, for which she has chosen the theme Being Safe Is Scary. And I think that she is also a maximalist in her effort of being here and now as much as possible ‒ losing herself in whatever she happens to be doing at the moment. It is worth noting that Katia graduated from the Moscow Institute of Steel and Alloys with a degree in Applied Information Technology in 2004; in 2008, while working as a project manager for the huge Western company that is Shell, she decided to start studying for a second degree ‒ in Art History ‒ at the Russian State University for Humanities ‒ to cross over to a completely different very soon.

‘I am doing this because I cannot not do this. I used to work in IT as a business analyst and project manager. And I left the job without any regret, simply because I needed to work in art. Curator is not just someone who is mounting exhibitions. It is someone who is bringing ideas to the public, helping artists, making sure that the artists work in a comfortable environment. An artist is focusing deeply on a particular area. A curator is assembling it all together, correlating the separate subjects so they become a concept.’

Muhammad Ali. Fears Fresh. Photo: Margarita Ogoļceva

Katia’s first curatorial projects were realised at the Que Vive Moscow International Biennale for Young Art. After that, she started working for the Vostochnaya Gallery and, alongside her main duties, with the artist MAKE also mounted a series of eight independent projects, exhibitions in a freight container. After obtaining her degree at the RSUH, she applied for the de Appel Curatorial Programme; founded in 1975 in the Netherlands, it is known as an influential educational platform in this field. A couple of years ago, following some time spent in Holland and a number of large exhibition projects realised in the country, Katia started her collaboration as a curator with the V-A-C Foundation, a key Russian art institution that is about to launch an ambitious cultural centre of its own, based in Moscow. And yet Katia’s country of residence is still the Netherlands, where she curates shows and teaches artists to do just that ‒ make exhibitions.

Sabian Baumann. Diving with Isabell (aus der Reliefserie). Photo: Margarita Ogoļceva

‘I try and make sure that I don’t tell any lies,’ says Katia. ‘Being an artist means constantly making choices. Even the smallest details can influence this choice and present the work in a completely different light. Curator in this situation is a guide, a mediator and a therapist. I take a work of art from its author, and I am responsible for the context I am placing it into. That is why I always ask the artist if they feel comfortable being shown next to this work or another. I always send them photos of who and what they are sharing the space with, so the artist would understand that I am taking their work seriously.’

Festival's venue - the former Museum of Literature and music, which is located on Terbatas street 75. Photo: Margarita Ogoļceva

Recalling the time that completely changed her life, Katia says: ‘I am like Alice in Wonderland. You make a single step, and then you just keep flying through the rabbit hole and looking at all the wonders taking place around you.’ Obviously, wonders do not just happen to take place by themselves. You must know how to work to make them happen, and work is the one thing that Katia Krupennikova is clearly not afraid of. Although the subject of fear as such is very important for her ‒ and it seems to be the key theme of the whole of 2020, the year that sees the latest edition of Survival Kit choose Being Safe Is Scary as its motto. The curatorial concept interprets it the following way: ‘Safety and security are central to today’s political imagination. They are used to provide rationales for wars, nationalist agendas, racism, inequality, and other reactionary attitudes and policies. [..] The politics of fear feeds upon precarity. Whole systems of domination are built upon the fierce illusion of protection, encouraging brutal competition and enforcing both financial and moral indebtedness.’ And it was with a discussion of a variety of meanings of this juxtaposition (and interdependence) of scary/safe that we started our conversation in one of the second-floor rooms housing a display of works by the Estonian artist Sigrid Viir.

I know that you arrived in Riga from Amsterdam in mid-August and, in keeping with the official regulations, had to spend 14 days in self-isolation. How safe did it feel for you and how scary?

To tell you the truth, it was wonderful. The first ten days I spent in Jūrmala, and it was exactly what I wanted ‒ to spend some time away from people. Compared with the rest of the world, Latvia on the whole seems like a strange little island of calm, almost as if it was existing outside of the Covid situation. We are opening an exhibition in the Netherlands in a month, and the rules are completely different over there. It is much more difficult to plan things there.

The subject of safety and fears ‒ how long ago was it that it came to you? And why did the phrase ‘Being safe is scary’ that first appeared in the public domain back during the 14th DOCUMENTA exhibition in Kassel become the key theme for the 11th edition of Survival Kit?

I started thinking about it in 2011 when I was still only my way to become a curator. At the time, I saw the Diktatur der Sicherheit graffiti campaign in Berlin; it was held in opposition to the omnipresence of public surveillance cameras. For some reason, it made a huge impact on me. I took a picture of the graffiti. It stayed in my archive, resurfacing from time to time. Between 2015 and 2017, I worked on an exhibition entitled Post-Peace about the boundaries of war, about the ways in which war ir present in our everyday life and the fact that the word ‘peace’ actually carries a somewhat aggressive meaning.

And the Being Safe Is Scary exhibition is probably a continuation of this interest. In 2017, when I saw Banu Cennetoğlu’s work, it also touched a chord with me and I found it very striking. I know Banu personally; we met in Istanbul when I was making Post-Peace. Afterwards we worked together at the Bergen Assembly. And I know that she takes very seriously everything that she does. For her art is not just an object but also an opportunity to spread information that does not appear in the media. She used some of the letters on the façade of the Kassel Fridericianum and made some additional ones, and that is how this sign ‒ Being Safe Is Scary ‒ appeared on the museum building.

And it occurred to me that it would be excellent if this statement would get a new lease of life. At the time when I was developing this idea and trying to find the right title, this work kept turning round and round I my mind. So I emailed Banu un asked her if I could use it. And she agreed. It matters to me that works like Banu’s stay in circulation, their life goes on and there is a continuation ‒ that the work lives on through other media, in other formats.

What I’m doing here is attempting to analyse the general ways in which a society operates and in which safety is ensured inside it ‒ not just in terms of war and borders but also everyday life, relationships and our own internal world.

Although, of course, I bring a new context to the whole thing. Now it’s not only about the things Banu meant ‒ that one person’s safety means violence against others. What I’m doing here is attempting to analyse the general ways in which a society operates and in which safety is ensured inside it ‒ not just in terms of war and borders but also everyday life, relationships and our own internal world.

Considering the fact that the theme has been maturing for such a long time in your mind, the list of participating artists must also have emerged some time ago. To what extent has it changed due to this year’s events? For instance, the recently-opened Riga Biennial makes a point of emphasising the ‘empty places’ that have appeared because some works could not be transported or even produced.

We do not have empty places of this kind. And in a way it seems improbable. The exhibition was, of course, ‘defined’ during the pandemic. But you see that the very subject ‒ Being Safe Is Scary ‒ is more topical than ever today. I haven’t changed a thing in the exhibition, apart from a few details of some works. A part of an installation could not be brought over from Beirut ‒ not because of the pandemic but because of the explosion on 4 August. We have some new works and perhaps they do allude to the pandemic, each in their own way. Because a few works, mostly be Latvian artists, were made exactly at the time. But we do not refer to it directly; there is no need to, because the pandemic only intensified the subjects we had previously considered focusing on. That is why nothing was really changed in the exhibition. It is very topical, and I find it almost shocking ‒ in a negative sense. So I am making an exhibition that, sadly, seems even more topical than it was at the time of its conception.

Katrīna Neiburga. Transformations. Witches’ broom. Thunderbesom. Photo: Margarita Ogoļceva

Could you tell a bit more about the works of the Latvian artists you mentioned, made this year, during the pandemic.

It is, for instance, a work by Katrīna Neiburga, made this spring and summer while she was self-isolating ‘in the woods’ with her family. It is, to an extent, a reflection of their thoughts and feelings at the time, although it is still a very fairytale-like and mythological installation in its own way. We discussed Evita Vasiļjeva’s site specific composition here in Riga in early March; we both left the country on 12 March. Then the borders started closing, lockdown was announced and it was not very clear if she would manage to make it or not, because the artist’s presence was necessary. Evita was in France, under a very strict lockdown; later, quite recently, she opened an exhibition as part of the satellite programme of Manifesta. As recently as a couple of weeks ago it still remained unknown whether she would manage to come back in time. For this reason, the pandemic is also present in her work, although the reference is not a direct one: instead, her work alludes to a permanent sense of fear and tension.

Or let’s take Evita Goze. Her piece is also a new one; we made plans regarding it back in the pre-pandemic times. But there were lots of reports of increased levels of domestic violence, of the dangers of spending so much time together in isolation. Evita was considering doing a piece on self-defence, and we chose the subject of self-defence in private life, in a space where you normally don’t expect to encounter violence ‒ at home. So that’s the third work of this kind; the fourth one is a project by Līga Spunde. She was working with the story of David Vetter, the so-called Bubbleboy who was born in the early 1970s completely without immunity of any kind and lived in a specially built bubble for 12 years. Sadly, he still caught an illness, and medics did not manage to save him. So now Līga is working with this story, intertwining it with her own history. It is a story of viruses, bacteria, of a search for protection ‒ and of the thin line between love, care and violence, hate and destruction. Overprotection ‒ because too much care can also suffocate, crush you to death. And there is also a reference to the pandemic in this.

Evita Goze. Fingerlocks. Photo: Margarita Ogoļceva

Yes, lots of coincidences. And we still have not wrapped our heads around the recent powerful experience when even a mundane trip to the supermarket was ever so scary… The line between danger and safety has been completely blurred.

Indeed, the boundaries of danger have been blurred. But what I found really scary during the pandemic was, in fact, the economic situation at a time when so many people lost their income, their jobs and ability to function normally – or were unable to receive timely medical help because health services, apart from the fight with the pandemic, was under lockdown. Or when elderly people were unable to see their families or even leave their house. All of that is very scary indeed. Not just the actual virus but also the whole context.

But is there a model that could and should be followed within this scary/safe dichotomy? Or can we just say that everything is getting worse and worse, the number of various of fears and restrictions is growing for the public, therefore there is no positive perspective in this situation?

I am not an economist or a politician ‒ as yet, at least. (Smiles.) But I think that we should re-examine our models of relationships, the economical one first of all. The pandemic showed how easy it was to transition from a familiar comfortable state of existence to a most unpleasant and vulnerable situation. I think we should start building communities on a micro-level. Because that much is clear that the state, operating on its level, cannot always help or help as much as we would like, or not the people who need help most of all ‒ namely, those it considers ‘unprofitable’. So we need to rethink the relationship between neighbours.

I think that we should re-examine our models of relationships, the economical one first of all.

Although I confess that I do not have a straight answer to that. Just the questions. I just know that the students I teach back in the Netherlands lost their ability to earn some money for their studies and subsistence. For me, the problem starts with the fact they have to pay for their studies at all. I believe that education should be free of charge. They worked so hard to cope with the insanely high housing as it was ‒ and now they have lost their ability to do even that. So first the government tells the universities to solve their problems on their own. And then the universities say that they will deal with their students on a case-by-case basis. That is how the neoliberal system works. ‘We are going to deal with it on a case-by-case basis.’ That is how people are precluded from grouping around any serious points of concern. The whole thing ended with the students forming a support group of their own. I am coming up with these examples because that is what I see happening with my own eyes.

I believe that education should be free of charge.

We must, of course, make significant changes, but we should not be hasty. We should start re-examining these things, trying to make sense of this new situation. Because we do tend to jump the gun, we do try to adapt to it. Whereas I think that we should search for new solutions. What could they be like, I cannot say as yet. In this sense, I can only transmit my sensations and premonitions through the exhibition.

Sigrid Viir, Office Sweet Home. Photo: Margarita Ogoļceva

Sigrid Viir, Office Sweet Home. Photo: Margarita Ogoļceva

But would you say that the scary aura dominates the exhibition on the whole? Or is is the other way round? We have settled down for the conversation in the area featuring works by Sigrid Viir. And it seems so colourful, quite positive. You can even have a lie-down here…

The exhibition is very diverse. There are both playful and more serious bits to it. And we are currently located in the more playful area. Sigrid’s work, however, deals with quite a serious thing ‒ regulation of our working hours. We have transformed into a society of entrepreneurs; everybody is independent, everybody is responsible for themselves. And that is a huge problem. Because the result is…

We have transformed into a society of entrepreneurs; everybody is independent, everybody is responsible for themselves. And that is a huge problem.

That we never rest?

We cannot afford to have some rest. We do not have this luxury. Because we are afraid that we would disappear from the map if we did not answer our mail for two weeks and took a break from communication – no-one would ever write to us anymore.

And that is probably how it will stay. We have grown used to the rat race. But the work is not just about the rat race and impossibility of getting some rest but also about the problem of the ratio between life and work and capitalism per se. We live in a competitive milieu where everybody is responsible for their own fate. No trade unions, no contracts. No guarantees, nothing. It is only the now that some understanding of the necessity for these things is beginning to emerge. As well as for letting each other take a breather now and then.

Sigrid’s installation resonates with The Stroker, a work by the Finnish artist Pilvi Takala. It deals with the story of her pretending to provide a special service at a coworking space of a London office full of all sorts of entrepreneurs: allegedly to make people feel more comfortable at work, she touches them and inquires: ‘How are you?’ Which actually generated a lot of pressure and hostility from the people who worked there. And that is the sound of another ‘pandemic’ alarm bell ringing: after all, a touch can be so desirable or undesirable under various circumstances.

Photo: Margarita Ogoļceva

What is your vision of the mission of Survival Kit? Do the previous editions form a sort of logical chain for you?

I only saw the previous edition at the Riga Circus as a ‘live’ show; the rest of the exhibitions I have caught up with online. But on the whole, at the time when we were having discussions on whether Survival Kit should be postponed, we spoke about the fact the festival was actually born out of a crisis, the 2008 economic and social crisis. And that is why we decided to not change a thing and open the exhibition at the scheduled date.

I was not sure if I would be able to come for the installation of the show for quite some time. Almost no-one of the non-Baltic-residing artists have been able to come. But the very festival was born out of a crisis, of empty spaces, of impossibility. And so we decided that we can very well make this ‘impossibility’ work today. On the whole, the works I have seen featured at previous editions of Survival Kit are ones that I would happily show myself, pieces that resonate with me. There is this section of art that I find interesting and that fits the Survival Kit tradition quite well ‒ the tradition of interaction with social and political contexts, with a range of topical issues. And that is why I think that Survival Kit and I operate in the same area of art.

Katia Krupennikova at the Sigrid Viir exposition. Photo: Sergejs Timofejevs

There are parallels.

Yes, there are parallels and intersections.

Title image: Līga Spunde. There’s No Harm In Any Blessings. Photo: Margarita Ogoļceva