Modern Love

An interview with curator Katerina Gregos

Currently at the Museum für Neue Kunst in Freiburg (Germany) there’s an exhibition focusing on an unusual and seemingly inappropriate phenomenon in the field of contemporary art. As the name suggests, MODERN LOVE (or Love in the Age of Cold Intimacies) focuses on love. A concept which, in the words of the curator of the exhibition, Katerina Gregos, ‘in contemporary times is usually sidelined from the ranks of higher intellectual pursuit and serious discourse as unworthy subject matter, something deemed superficial, cheesy or nostalgic. Today, love issues mostly reside in the domain of commercial culture, in soap operas and romantic novellas, rather than in high art’.

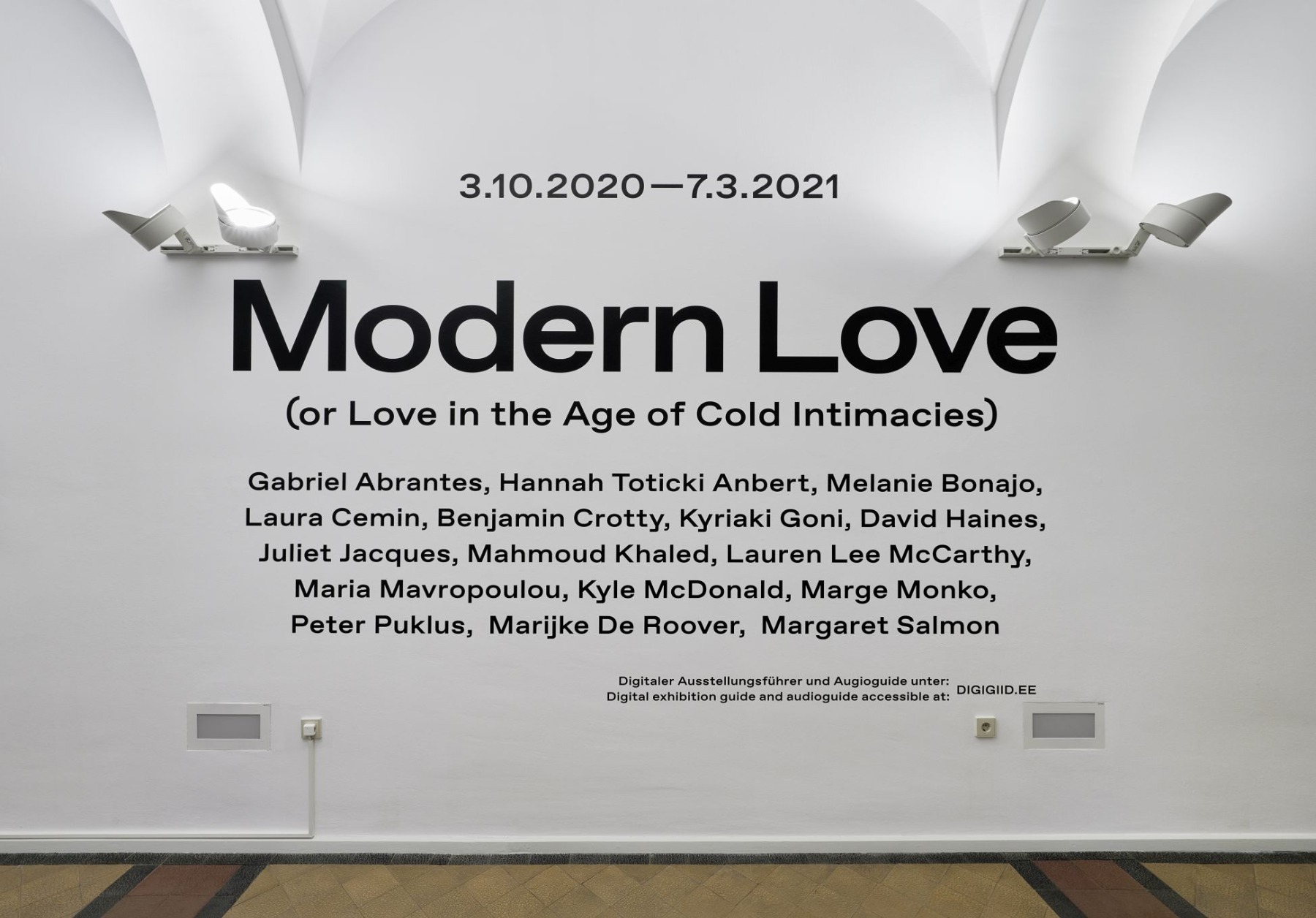

The story of MODERN LOVE (or Love in the Age of Cold Intimacies) is told through the works of 16 artists. It will be on view at the Museum für Neue Kunst, Freiburg, through the coming spring – until 7 March 2021. Thereafter it will travel to Tallinn Art Hall, Estonia (12 June – 5 September 2021), and IMPAKT in Utrecht, the Netherlands (27 October – 12 December 2021); the exhibition is a co-production between these three institutions.

Arterritory sat down with curator Katerina Gregos to find out more about the exhibition.

The exhibition "Modern Love (or Love in the Age of Cold Intimacies)" at the Museum für Neue Kunst in Freiburg.

Marge Monko, I Don't Know You So I Can't Love You, 2018. Courtesy of the artist

How was the concept of MODERN LOVE born? What was the trigger that turned your attention to a topic that sounds so unfashionable in the context of today's art scene?

Like other fields and disciplines, prejudice and biases are also present within the field of art, no matter how ‘open’ or ‘progressive’ we might like to think it is. There is still a consensus about what constitute the ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ kinds of exhibitions or the ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ kinds of subject matter. Love indeed happens to be, as you say, one of those ‘unfashionable’ subjects, precisely because it is mistakenly thought of as being a superficial or ‘corny’ line of enquiry, something which is cheesy or nostalgic; though it’s hard to understand why, as love is not only a highly complex emotion but a cardinal, ecumenical one at that. One could also argue that love in the modern age has been degraded as either a volatile, unhinged, untrustworthy emotion, or as a saccharine, sentimental, flawed passion that is thought to be lacking in comparison to the more noble pursuits of reason and restraint. As a consequence, it is nothing other than this kind of prejudice and a rather dogmatic or clichéd form of thinking that has sidelined love from the ranks of higher artistic pursuit and serious discourse as unworthy subject matter. It is therefore not surprising that love issues mostly reside in the domain of commercial culture, in soap operas and romantic novellas, rather than in high art. In the field of contemporary art, there is still a strange skepticism surrounding this fundamental human emotion. But love can move mountains and radically transforms human beings in ways unlike any other force. As such it would serve us well to study it more closely, especially today in the climate of arch-individualism and egotism. I have always been interested in the different parameters and expressions of love as a personal, political and social force; I was very much inspired by Alain Badiou’s book “In Praise of Love” and also Srećko Horvat’s “The Radicality of Love”, two philosophers who have not shied away from the subject; and in 2017 I curated an exhibition for the Schwarz Foundation called Summer of Love, which was inspired by Michael Hardt’s ideas on political love. This exhibition is again, not about love in general, but rather about love and intimate relationships in the age of the Internet, social media, neo-liberal capitalism, and globalisation. Modern Love (or Love in the Age of Cold Intimacies) thus probes the societal patterns and challenges as well as possibilities that the Internet and social media present to our most intimate relationships.

The exhibition "Modern Love (or Love in the Age of Cold Intimacies)" at the Museum für Neue Kunst in Freiburg. Photo: Bernhard Strauss

How does this exhibition fit into the context of the ongoing pandemic, which is creating an eerie background for everything and everyone nowadays?

Well, the exhibition has been two years in the making and it began in 2018, long before Covid-19; but unfortunately, it fits perfectly into the context of the pandemic since the virus has obliged us to change the ways we physically interact with other people, resulting in yet another form of ‘cold intimacy’ – to borrow that phrase from Eva Illouz’s book Cold Intimacies: The Making of Emotional Capitalism – that of physical and social distance. During this time, our ever-increasing technological and digital dependency has been amplified, and close, physical social contacts and exchanges – in my opinion, the ‘glue’ that keeps societies together, have been diminished. We don't know for how long, nor what the repercussions of physical and social distancing will be in the long-term. It is quite possible that we will come out changed in this respect, and those common, basic codes of body language and physical behavior between humans will be transformed. I hate to think that even after the virus subsides or disappears, that we still will be thinking twice about whether to hug, kiss, or shakes someone’s hand.

The exhibition "Modern Love (or Love in the Age of Cold Intimacies)" at the Museum für Neue Kunst in Freiburg.

When explaining the concept, you wrote: ‘The exhibition looks into how the digital sphere, the technology giants and neo-liberalism have transformed love and social relations, while at the same time dissolving the barrier between public and private’. The past few months have made our lives even more digital than ever and, at the same time, have awakened existential thoughts and feelings. We start to appreciate more physical contact and have understood that screens create a wall that doesn't allow for intimacy. Maybe this is a starting point for a revaluation of values?

There is no doubt that digital technology and social media have significantly transformed social relationships, more so now due to the pandemic. The experience of the virtual has increasingly dissolved the boundary between private and public. This influences how we communicate and interact with one another, especially with those closest to us. The Internet and digital media, in themselves, are not ‘good’ things or ‘bad’ things; what matters is the way they are deployed and used. On the upside, they have facilitated communication and exchange or democratisation of information, particularly now in the time of Covid-19; they have also played a role in promoting social movements, activist practices, connecting people in difficult circumstances, or allowed for the expression of non-heteronormative identities, forms of desire, and alternative ways of being. On the downside, they have played a problematic role in cultivating pathologies – such as workaholism, narcissism, obsessive self-performativity, and digital dependency within relationships – and the commodification of emotion. So yes, I do agree with you, these are apparatuses that have also fostered alienation, a false sense of belonging and friendship, and existences lived in bubbles; and digital isolation also leads to loneliness and isolation, which, as a result, can lead to extreme ideological positions. It’s worth reading an article that was published in the Financial Times weekend edition recently, entitled ‘The Lonely Crowd’. As a second wave of Covid-19 prompts the return of limitations on social interaction, the author examines how loneliness has become a defining emotion of the twenty-first century. To me, there is no doubt that, no matter how useful the digital media are, they will never be able to replace real physical human interaction. It’s not only the intimacy, as you say, that is lacking, but also the inter-communicational nuances which cannot be discerned, the spontaneity, the improvisation, the surprise reactions and the interactive relationality that all disappear behind the screen. With rising levels of atomisation and loneliness particularly in more developed urban centres, clearly we need to reconsider our values and priorities. For me, nothing can beat the rewarding sense of joy, reciprocity or even disagreement or debate, that is the result of real physical interactions between humans, which are – lest we forget – social animals.

The exhibition "Modern Love (or Love in the Age of Cold Intimacies)" at the Museum für Neue Kunst in Freiburg. Laura Cemin, The Warmth, 2017/2020. Photo: Bernhard Strauss

The loss of love, the loss of empathy, has left marks on our lives. Psychological diseases are one of the most visible among them. In some way, Xanax and other antidepressants rule the world. How could we come back to life without all of that? Perhaps we have to return to nature to find out how to live in harmony with ourselves and the world around us?

It’s all a question of priorities and of striking a balance in one’s life between life, love and work. It’s not rocket science. Clearly the human relationships that matter to us most must be the ones we valorize, cherish and prioritise. Nurturing these relationships, restoring a sense of community around us, caring for our nearest and dearest are, to me, basic human values that somehow got lost in the whirlwind of industrial modernity, capitalism, competition, consumerism and the accumulation of practically everything. Returning to nature, as lockdown also showed, is very therapeutic and also can equilibrate our demanding lives. But it is not enough to partake of its riches; we must actively help to protect it because with the gravity and scale of the environmental crisis at hand, soon we will have nothing to fall back on.

The exhibition "Modern Love (or Love in the Age of Cold Intimacies)" at the Museum für Neue Kunst in Freiburg. Hannah Toticki Anbert, Framing Presence, 2020; Background: Marijke de Roover, Niche Content for Frustrated Queers, 2019-2020. Photo: Bernhard Strauss

Artificial intelligence is already here. What does that mean for us? Could it make our mental space even more complicated?

I don't think we can even imagine the long-term repercussions of this kind of technological progress. We are in the stone age of these developments. I am not a scientist, but if things are pretty complicated already, I can imagine they are about to become even more so. The problem is not only the ethical implications in this respect, but the fact that these changes are coming at an ever faster pace, are being normalised without being properly evaluated or digested, and that the time for adaptation is shrinking. Human beings are better equipped than all other species to deal with change; but in the past, change has been slow and humans have had the time to adapt. Since the advent of the industrial revolution, and now more so with the digital and technological revolution, there is no longer ample time to process change. I think the most threatening aspect of AI is that it can do things that we cannot foresee and might finally might escape our control. According to Nick Bostrom (director of the Future of Humanity Institute in Oxford), rapidly advancing research into artificial intelligence could lead to a so-called ‘superintelligence’ that could threaten our survival (the subject of his book of the same name). And Stephen Hawking (whose speech facility was itself based on AI) stated that ‘the development of full artificial intelligence could spell the end of the human race’, as it could become self-aware and supersede humanity. This would normally be the subject of sci-fi movies, but it is no longer a far-fetched possibility. So one might say that AI has the same kind of characteristics as any other great invention; it can be used for good and for evil purposes. Less scrupulous researchers, rushing to develop High-Level Machine Intelligence, might ignore sensible safety mechanisms, for example. In relation to love, one may think of developing smarter matching programs for internet dating, and developing ‘love robots’ for the lonely. This is already happening, with elderly people being assigned care-robots. Personally, I find the latter excruciating, no matter how ‘useful’ it might be.

The exhibition "Modern Love (or Love in the Age of Cold Intimacies)" at the Museum für Neue Kunst in Freiburg. Maria Mavropoulou,

Anniversary Dinner from the Family Portraits series, 2018. Courtesy of the artist

There are 16 artists participating in this project. What do they all have in common?

Social relations and questions of identity and self-performativity are at the heart of many of the works, but beyond that there are also the issues of how to grapple with the problematics of the internet, social media, and dating site use; how to make sense of the conflation of reality and fantasy which is the result of the virtual, digital sphere which has created complex psychological, mental and relational entanglements; how to negotiate the boundary between private and public and, of course, how to strike a work-life-love balance.

Photo: Bernhard Strauss