About Women Who Take Care

A conversation with the Artistic Director of the National Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens (EMΣT), Katerina Gregos, on what might change if women ruled the world and how to make a contemporary art museum a magnet for the new generation

On the opening day of seven exhibitions from the final, fourth part of the year-long project WHAT IF WOMEN RULED THE WORLD?, I catch the director of the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Athens (EMΣT), Katerina Gregos, as she leaves the museum building for a walk with her dog, Éclair. "After my mother passed away, our two dogs were left without care – and that was, honestly, one of the reasons I moved back to Greece, in addition to the museum." Even on a day full of meetings, conversations, and events, Katerina finds time for a walk with Éclair. "Our museum is pet-friendly. You can easily visit with your pet, also inside the exhibition spaces. And in the couple of years since we made this decision, there have been no “accidents” or problems." Caring for others, caring for loved ones, caring for her work and the team she works with – this seems to be one of the most significant traits of Katerina as a person and a professional.

Katerina Gregos and Éclair

We first met in Riga in 2017, when she came as the curator of the upcoming first Riga Biennale (RIBOCA). Before that, she led Argos – Centre for Art and Media in Brussels, worked for four years as Artistic Director of Art Brussels, curated the pavilions of different countries at the Venice Biennale twice, and organized quite a few internationally significant expositions. After the Riga Biennale, Katerina curated the impressive project MODERN LOVE (or Love in the Age of Cold Intimacies), a traveling exhibition that was seen in Estonia (at the Tallinn Art Hall), as well as in Germany and the Netherlands. In May 2021, it was announced that she accepted the offer to head the EMΣT. By then, the museum had spent 15 years (since 2000) as a nomadic platform, acquired its building – a former industrial structure (FIX brewery) in central Athens – in 2015, but its collection mainly consisted of gifts from patrons and was 96% composed of works by Greek artists. Gregos fundamentally rethought the museum's mission (there is even a special document titled just that, which can be read here). "Part of our core mission will be to look at the culture and histories of the Mediterranean, the Balkans, the Middle East, and North Africa," she told Frieze in June 2021. In 2022, under her leadership, the museum relaunched, published its program, and from December 2023 to November 2024, the EMΣT presents a cycle of exhibitions, in four parts, exclusively dedicated to the work of women artists or artists who identify as female, under the broader umbrella title, WHAT IF WOMEN RULED THE WORLD? Over the course of 2024, this cycle has presented a total of 18 solo exhibitions, installations and projects, highlighting the work of 40 women artists. The fourth and final part of the cycle, consisting of seven solo exhibitions, started in mid-June. At the same time, part of the exhibitions from the previous rounds can still be seen in the museum.

This is not the first major exhibition project featuring women artists, but perhaps the first of its kind in a major public museum. Why was this conceptual choice made, what could a world moving away from the patriarchal model look like, why has the museum's regional coverage expanded so much, and what is the youth (as Gregos herself says, "this Greek young generation that has grown up with crisis") looking for in the exhibitions happening there – this is what we discussed after a walk with Éclair, right in the museum café, a couple of hours before the opening and a big party on the museum's rectangular roof, where electronic music played until midnight, and the Acropolis, like a very older brother of EMΣT – a brother in discussions and reflections – towered to the left on the top of a rocky hill.

Yael Bartana, "What if Women Ruled the World", 2016. Neon light installation on the North and South façades of the EMΣT building. Photo by Panos Kokkinias

There’s this sentence if the Mission of EMΣT which I think is a very significant for the model of museum you and your team are creating: “At a time of institutional crisis and the proliferation of the globalist, one-size-fits-all franchise museum model, EMΣT carves out its own position, true to the hybrid identity of Greece, a country shaped both by Eastern or Levantine as well as European and Western influences”.

Yes, there are wonderful narratives, our “own” narratives. Our problem, especially in the 90s, was our desire to become part of the international mainstream. We largely imitated what was happening outside instead of looking at our own culture and modern history. I'm not even talking about antiquity, but the last 200 years of our history – a massive refugee crisis in 1922, with 2 million people displaced due to the Greco-Turkish war; the newly founded Greek state, the influence of the great powers, two world wars, two civil wars – it's a history filled with trauma, suppression, and marginalization. It's a classic case of "if you don't know where you came from, you don't know where you're going." We were thrust into this European narrative – Europe, Europe, Europe, which of course was a boon for the country. But Greece has a hybrid history, with one foot in Europe and one foot in the East. Here, cultures, diasporic currents and religions merge and confront each other, yielding rich and often unknown, forgotten or marginalised narratives. Acknowledging that it is impossible to include all contemporary art from all over the globe in the collection, the museum looks into the multiple narratives of its own regional historical, political and cultural inheritance, in addition to specific global issues that concern us all. Our temporary exhibitions programme is, on the other hand, global – focusing on practices that cast a critical eye on society at large and its political urgencies, examining key issues of our times such as democracy, governance, equity, economics, the environment, the effects of globalisation and the dominance of technology, while highlighting the importance of public life and dialogue.

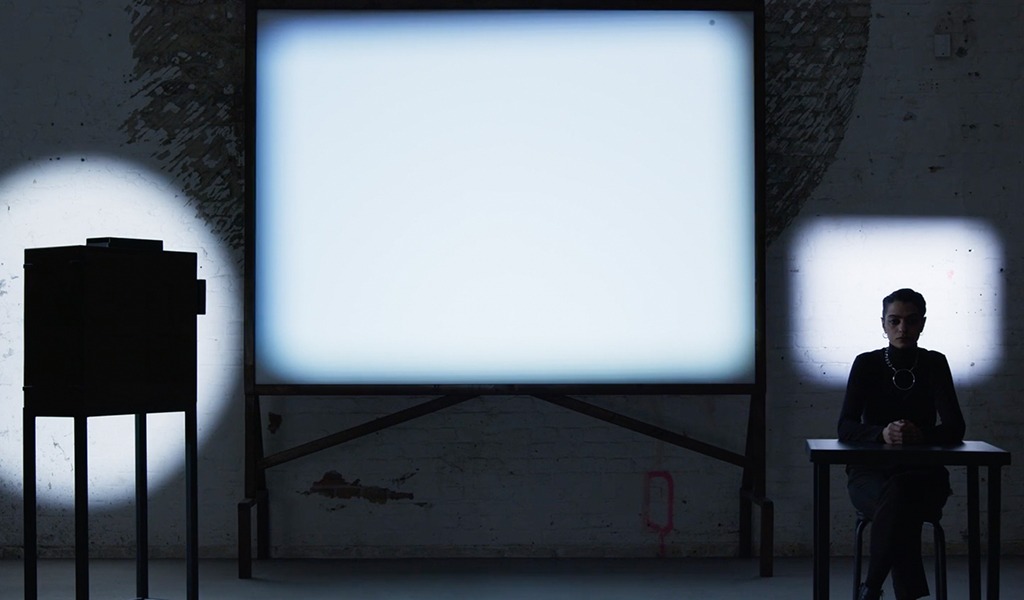

Yael Bartana, "Two Minutes to Midnight", 2021. Video still. Courtesy of Capitain Petzel Gallery, Berlin; Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam; Sommer Contemporary Art, Tel Aviv; Galleria Rafaella Cortese, Milan and Petzel Gallery, New York

Talking about global issues... From December 2023 to November 2024, EMΣT presents a cycle of exhibitions in four parts, exclusively dedicated to the work of women artists or artists who identify as female, under the broader umbrella title, 'What if Women Ruled the World?' Do you see any visions of how things should change, or models for the future in the works presented at the just opened complex of exhibitions, which is the fourth part of this project?

The artists here are not necessarily discussing how women would ‘rule’ the world. However, they are addressing global issues, some of which pertain to gender equality. A notable example is the video in the mezzanine by Yael Bartana, entitled ‘Two Minutes to Midnight’. It originated from a performance where she created a crisis situation involving a significant global conflict on the brink of nuclear war. She envisions a scenario where all global leaders are female. Specialists, in fields like defence, peaceful activism, philanthropy and politics, and actresses, investigate ways to de-escalate international crises, contemplate whether it is better to die for an act of peace than survive a pre-emptive killing, and analyse the macho aspects of war. In this deeply anti-war work, Bartana treats serious issues with humour but also highlights practical ways of dealing with global threats in an alternative way. There’s a “bad” guy – you can imagine someone like Putin or Trump – who is a man, obviously, and he wants to lead the world into war. The video shows how women actually react to this crisis.

Another answer is women who contribute long-term to creating change within their respective communities, regardless of their vocation. For example, one of the artists with a solo project, Swiss artist Claudia Comte, moved her studio to the countryside in Switzerland, into a former chalet. She is creating an incredible space where her studio coexists with exhibition spaces, gardening, a bar forming an oasis and exceptional working conditions for the extended community of people who work with her. I visited last week when I was in Basel, and it’s simply a small piece of Paradise. Comte has created a microcosm where everyone is treated well. This addresses broader questions about problematic labor practices and precarity, which are prevalent in the art world, where many are underpaid and interns and assistants often face poor conditions. Claudia is highlighting these issues through her day-to-day practice, not just through her artworks. And that’s where politics starts, by practicing what you preach, not just by talking about it.

Bouchra Khalili. The Magic Lantern, 2020-2022. Video installation (film and objects). Video still. Courtesy of the artist and Mor Charpentier, Paris/Bogota

And then, obviously, in a work by Moroccan-French visual artist Bouchra Khalili called ‘The Magic Lantern,’ there is a reference to Swiss feminist video pioneer Carole Roussopoulos, who extensively used video to highlight the struggles of feminist activists in the women’s liberation movements. Khalili’s installation takes as a starting point ‘The Nero of Amman’, the lost first video work Roussopoulos. The film disappeared due to the numerous projections that erased it, as at the time, a master tape would have served for both filming and broadcasting. Similarly, American Magnum documentary photographer Susan Meiselas's project ‘A Room of Their Own’ is a multi-layered, visual story that explores the lives of women who are survivors of domestic abuse in the Black Country, a post-industrial region in the UK. It focuses on women who are received by other women in a safe space after escaping domestic violence.

There are also other works in the series of exhibitions, such as those by Lola Flash, a black queer photographer who has been working on the ongoing project SALT since 2011. It is a series of portraits celebrating iconic women over seventy who have quietly made their mark on the world and remain passionately engaged in their life’s work. In a society that often equates beauty with youth, these women stand out not only for their beauty but also for their significant accomplishments and contributions. This intimate series captures their wisdom, charm, and strength – qualities frequently overlooked due to ageism. But it’s really not just the artists themselves but the series overall that asks the question: 'What if Women Ruled the World?'. It’s a hypothetical one that requires a leap of the imagination.

And there is the re-hang of the collection, with women only, entitled WOMEN, together, which is a very symbolic phrase. This infers that though the patriarchy is largely responsible for treating women unfairly over centuries, there is often a lack of solidarity among women themselves, especially those who have adopted patriarchal patterns of behaviour to survive in male-dominated workplaces. In that sense, let’s be honest: there is not only toxic masculinity; there can also be toxic femininity. So the idea is, how can women support and help each other? First of all, by being in solidarity with one another. One of the reason the ‘old boys club’ dominated for so long is that they stuck together. Women must build coalitions of solidarity to counteract that. There are historical paradigms but we need more.

Lola Flash, "Ilona", 2012. New York, NY, USA. Coloured photograph. Courtesy of the artist

Actually, quite a few art institutions today are led by women. Is this sphere a good example of how women can collaborate, creating something with the spirit of solidarity that you mentioned?

I think it depends. Being a woman doesn't necessarily make you a good director or leader, especially if you have been schooled in patriarchal paradigms, as I said before. While, women can be excellent leaders, as they are multi-taskers, the problem arises with women who try to act like men in order to exercise governance or power. The difference should be in leading as a woman, not in leading like a man.

Just because a woman is at the head of an institution doesn't mean that the governance is necessarily good. If this person is dictatorial, toxic, or behaves in a very authoritarian, hierarchical manner, then that’s not the example of leadership we want. My understanding of female leadership is that it is definitely more caring, involves more compromise, and emphasizes listening. Female leadership that is not authoritarian but engages in discussion, even in disagreement, to reach a consensus. It also involves using humor and play, not taking oneself too seriously, and staying humble. This is how I understand female leadership: being approachable to everyone around you, including your staff and peers, and being open, while sticking to your vision, values and goals.

You might ask, 'What's the difference between men and women?' There are differences. I think men are often more ready to jump into conflict, ready to go into a fistfight. The kind of women that I look to are those who take care of other women but do not discriminate against men on the basis of their gender. In trying to address the age-old discrimination against women, the pendulum sometimes swings too far the other way, with the sentiment that all men are bad, and a ‘kill the patriarchy’ attitude. Of course, there has been a patriarchy, there still is a patriarchy, but let’s also not put all the male gender into one basket. We must remember that there are men who are feminists, too, and we need to eventually strike an equal balance in our societies, of race, gender, everything.

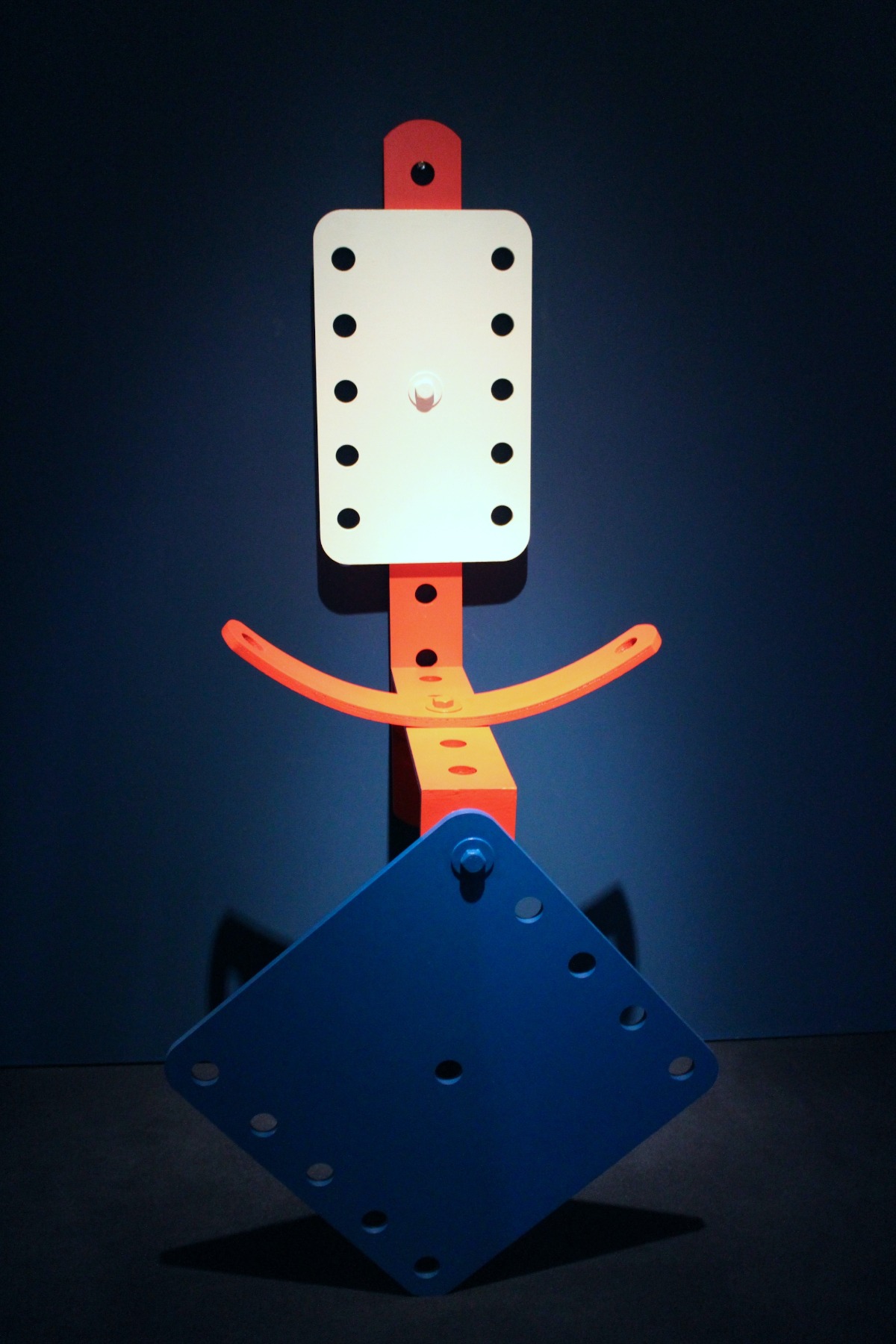

Claudia Comte, "How to Grow and Still Stay the Same Shape",

Performance at ΕΜΣΤ| National Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens. Photo by Eftychia Vlachou. Courtesy of EMΣ

But how can male artists be part of this process? What could be a good model for them to participate in changing the trajectory in the art world or in a broader social context?

This is a very difficult question for me to answer. But to start with by not discriminating against women and being inclusive when they have the power to do so.

But can male artists authentically and convincingly address feminist issues?

I believe that artists can address a wide range of experiences and subjects. However, to discuss something meaningfully, you must be very committed, engaged, and well-versed in the subject. You need to be sincerely interested in contributing to the topic rather than simply representing it and accruing symbolic capital for personal gains, in the process. Art is also about making leaps in the imagination, which should allow artists, responsibly, to engage in any issue that genuinely interests them. Obviously it’s not easy to engage with someone else’s experience or circumstances that’s why one must include the people you are talking about in the discussion and process.

You can ask, why are there no men in this show? It's not because I want to discriminate against men, but because, especially in this country, there has never been a history of feminist art practices, for one. For the last ten years, Greece has also ranked – systematically – at the bottom of the Gender Equality Index in Europe. Women have been systematically marginalized both artists and otherwise. Feminism wasn't even discussed; until recently it was considered unfashionable. Twenty years ago, when I curated a show as then director of the Deste Foundation – Centre for Contemporary Art entitled ‘Fusion Cuisine,’ which aimed to put the subject of feminism on the table because nobody was talking about it at the time, also in the art world. At the time, the reaction was, ‘Feminism? No, that's finished, it's done.’ Of course, that wasn't true. Things have changed, with the younger generation, but still it was important to me to make a strong institutional statement and emphasise the ongoing importance of the discussion and create this space of discussion. And once we create this space, maybe we can meet each other halfway. This is how I understand it.

Mary Reid Kelley and Patrick Kelley, "The Rape of Europa", 2021. Video still. Courtesy of the artists and the Gardner Museum

In the contemporary world, we are influenced and shaped by many factors, such as gender, nationality, financial status, and so on. These factors also compete with each other for influence over us.

The problem is that everything is becoming very compartmentalized and territorialized and we are not talking to each other. This compartmentalization happens precisely because some groups have been systematically discriminated against so of course they need to create safe spaces and to protect these spaces. Once we achieve greater equality, I hope people will open up more people beyond their close-knit communities.

I don't know if we should mention it in this context, but you were also the curator of the first Riga Biennial (RIBOCA) in 2018. The third edition of this biennial was stopped just before its launch in 2023. This situation can be viewed from different perspectives. From a gender perspective, the Biennial's organizational team was predominantly female from the very beginning. The planned exhibition in Riga in 2023 was supposed to consist solely of works by female artists. However, after 2022, in the context of the Russian aggression in Ukraine, this structure faced heavy criticism, mostly from women – curators, art critics, and artists.

I think that this was a loss for the local and international art community because the Riga Biennial was modelled on best practices and actually tried to do the ‘biennial’ in the right way, to me the war in Ukraine was not the only reason it was attacked. Nevertheless, women who actually make waves, and create significant change and opportunities, like Agniya Mirgorodskaya, Anastasia Blokhina and the RIBOCA Team did in Riga, should be supported and not silenced as was the case. I think what happened with the Riga Biennial wasn’t fair. They did a fantastic job in establishing an international biennial with excellent conditions, strengthening Riga's position on the global art map, and providing new opportunities to many artists from the Baltics. With the cancelling of what started as an excellent and critically acclaimed biennial (in the words of the international press, not mine), everybody loses and the Latvian and regional art community becomes poorer. Healthy competition is good, it means more voices, more variety, more ideas, more exchanges, how can you want to make your world shrink?

Installation view of the Collection exhibition: WOMEN, Together.

ΕΜΣΤ Collection, works by

Hera Büyüktaşcıyan and Maria Tsagkari. Photo: Paris Tavitian

But this also leads us to the question of money and its sources. As I understand, you’re very concerned about this as the director of the museum?

I'm very lucky because we're a publicly funded museum. This means our money comes from the government, as well as from our own income through our restaurant, shop, and ticket sales, thanks to our good attendance. However, if I have to fundraise in the future – and I probably will – I will not accept money from questionable sources. There's nothing inherently wrong with the relationship between art and money, but you must be very careful about where you take your money from. Additionally, rule number one for me is that the museum should be the one calling the shots in terms of content and programming, that should go without saying. This is why I'm quite skeptical of the American model, where museums rely heavily on private money, allowing wealthy individuals to influence collections, programming, and more. For me, there can be a synergy, but it's the museum and its experts who must have the first word, ensuring that everything happens within the policy framework and mission of the museum.

In 2022, we received a major donation from Dimitris Daskalopoulos's collection, the largest and most important in our history, which included 140 works. This donation was part of a larger gift of 350 works that he split also between Tate, MCA Chicago, and the Guggenheim. Daskalopoulos gifted the works with no strings attached, saying, 'You choose what you want. You're free to use it creatively.' And he did not ask for anything in return. This is what I consider true patronage and it’s rare that it does not come with strings attached. This led us to create a curated exhibition where we re-hung the collection that combined these donated works with works new acquisitions from our own collection. The exhibition that is on view is entitled Women, Together, as I mentioned further up and features women artists alone. The show also highlighted our new collection policy as a museum: to highlight art from South-eastern Europe, the Balkans, the Middle East, North Africa, and the Mediterranean more widely.

Eleni Pitari-Pangalou, Untitled, c. 1960-1970. Ink on paper. Maioletti-Pitari Collection

But EMΣT is also a National Museum. How do you see the perspectives and effective ways of bringing Greek art into the international context? Perhaps through the subject of the diaspora?

Well, of course, we're the National Museum, which is a bit of an anachronistic label. Obviously, our programming is international and regional. At the same time, we have a duty to support Greek artists of different generations and address gaps in contemporary Greek art history, paying attention to artists who have not been properly acknowledged. In that sense, we are also considering the Greek diaspora which is spread far and wide. Right now, for example, we are showing a retrospective exhibition of the important South African artist Penny Siopis, who was born to Greek parents.

Many thousands of Greeks were forced to emigrate from the beginning of the 20th century due to the country's poverty and lack of opportunities. You can find Greeks in almost every country around the world. Everyone knows about famous Greeks like Kounellis, Xenakis, Samaras, Takis. But there are many other lesser known but also accomplished individuals who were the sons and daughters of migrants living in very difficult post-war conditions. Greeks have made significant and yet mostly unknown contributions to culture and science. This is one of the aspects of our cultural history I want to explore. Penny Siopis is one of these examples. She doesn't speak Greek, but she carries the entire history of the Greek 20th-century diaspora, which is a very difficult history. In South Africa, her parents were white but were still second-class citizens because they were Greek.

So, yes, we support Greek artists or artists of Greek origin in our exhibition programme and collection, but that is not enough. That's why we started an International Curators' Visiting Programme, funded by the EU, where we invite museum curators and directors to come to Greece with all expenses paid. We create custom-made programmes based on their interests, allowing them to meet Greek artists who are working on issues that interest them. This is the best way to promote Greek artists internationally. We can't, obviously, all Greek artists, we try to promote them more broadly in this way, opening up opportunities for them in this way. We are also starting a programme, supported by the EU, to fund residencies for Greek artists abroad, helping them gain more visibility. The museum is now quite well known internationally. About half of our visitors are non-Greek, and we attract many from the international art world. These visitors also come into contact with the Greek artists exhibiting in the museum. So, you have to use a variety of strategies.

Penny Siopis, "Pinky Pinky: Blue Eyes", 2002. Oil and found objects on canvas. Private collection of Teresa Lizamore, Johannesburg. Photograph: Courtesy of the artist

For you, this job was also a very new position and quite a challenging mission. Was there anything that surprised you in your work as a EMΣT director?

What surprised me the most is the enormous number of young people coming to the museum. For many years the museum in its new building was an unfulfilled promise. For the first 15 years, it existed as a nomadic institution before moving into its permanent premises, the former FIX brewery, an industrial modernist landmark in Athens, in 2015. But it was in the middle of the crippling financial crisis, and there was little money to do much. In 2017, Documenta 14 used it as one of its main venues in Athens. Then followed a prolonged crisis period without a director for three years, making it very difficult for the museum to function properly. The collection was finally installed in 2020, but then COVID hit. So, from 2015, when the museum moved here, until 2020, it was only functioning partially.

Before we launched the full museum programming for the first time in 2022 – regular temporary exhibitions, continuing activities and public programme and systematic renewal of the collection – it took me more than a year to get the institution back on track. Prior to our first opening in 2022, I asked our head of press how many people attended the opening of Documenta in 2017. She said 2000 people. I thought if we could have 1,000 or 1,500 people at ours, I would be very happy. But over 5,000 people came; we couldn't believe it. The biggest surprise for me was how the most difficult audience group, younger people, embraced the museum. This means we must be doing something right.

Installation view of the exhibition: Chryssa Romanos. The Search for Happiness for as Many as Possible. Photo: Sergej Timofejev

But what is this that young people can find in the contemporary art, which you are exhibiting?

I think they can find that we deal with many issues that concern and worry them. From climate change to gender issues, from the impact of social media and the Internet, to globalization and living at the edges of Europe. They can also discover their recent history which is not taught in schools and the legacy of being a country that experienced dictatorship, experienced the crisis first hand, and is now part of a Europe in worrying turmoil. This Greek young generation has grown up in uncertainty. We address all the issues they are concerned with systematically. Additionally, we strive to create exhibitions that are both critical and aesthetically rewarding. We discuss politics, but we always do so through the language of visual art, not merely through documentation and activist practices.

My son is 17, my daughter is 14. And when they were very small, I would never imagine that we will live in the world, which is now around us. With epidemies and wars at our doorstep.

No one imagined. We became adults in the post-1989 promise…

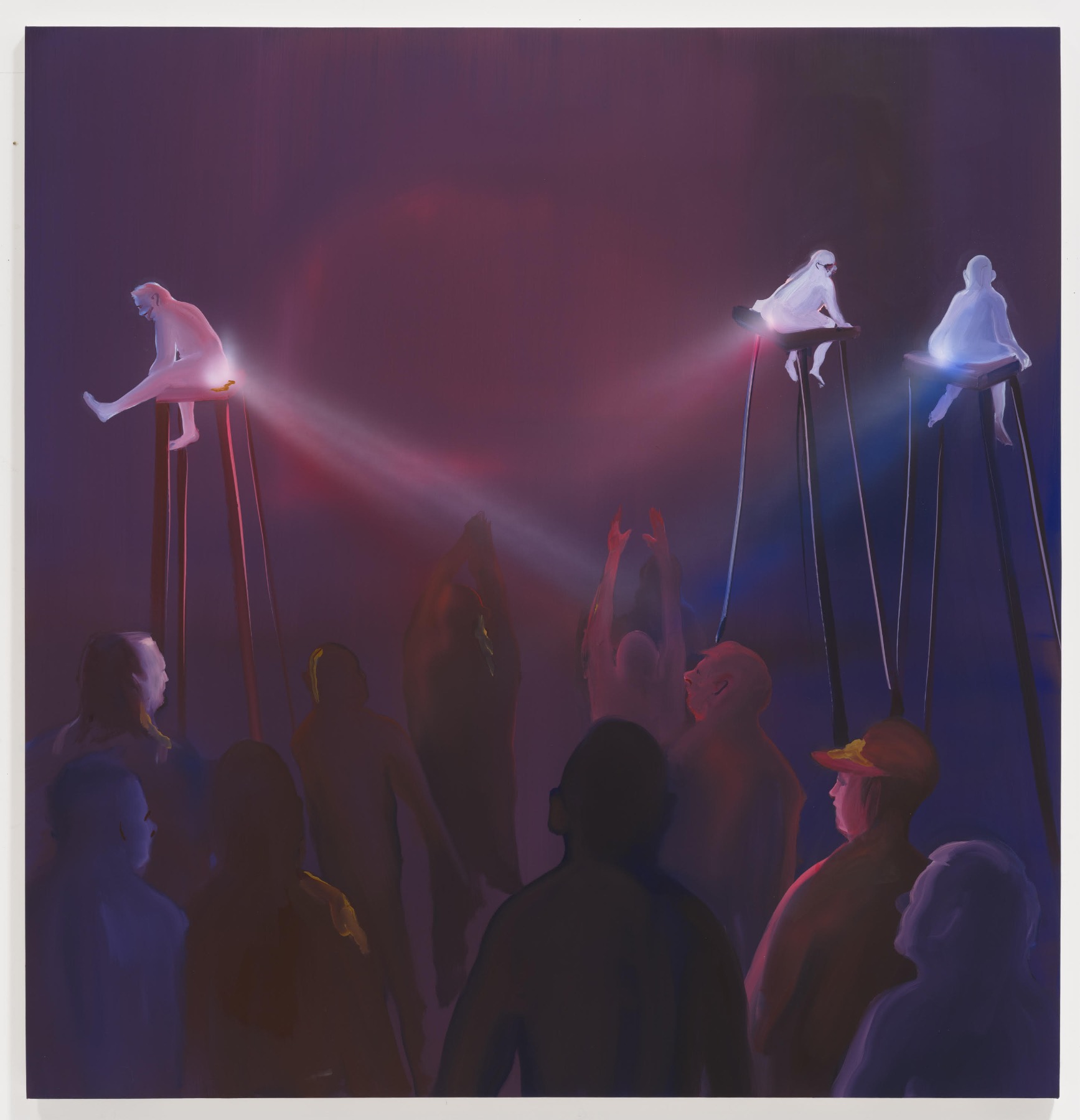

Tala Madani, "Shitty Disco", 2024. Oil on linen,152.4 x 147.32 cm .Courtesy of the Artist and Pilar Corrias, London

But do you still believe that humanization, culture, and the arts can have a significant impact, not just specific effects on individual lives? Can they change the direction in which society is moving?

Artists cannot change society directly; this is a cliché question and virtually impossible. However, artists can change the way people think about society and the world, by opening up new horizons of perception and thought. Measuring this impact is very difficult because it always happens on an individual level, and you cannot quantify it. In that sense, it's not about the number of people who visit the museum, but about what they take away from it and how they are affected. I can see that we are now shaping a new generation in this museum, and I believe we will see its full impact on society in 10-15 years. I see it happening every day.

Culture is a very important way to think about the world. Because everything has become so compromised and monetised, culture is the last place where people still think humanistically and progressively, where so many artists address issues that nobody else is discussing or don’t want to discuss. For example, in Belgium, where I lived for many years, nobody was talking about colonialism and decolonialism fifteen years ago. The first people to do so were artists.

In Greece, until now, private foundations have dominated the contemporary art world. There's nothing wrong with that – we have very good private foundations. But it was important for the public museum to take a clear stance and to start setting an agenda that has social concerns at its core. We believe very much in the role of a museum as a producer of knowledge about our world and about the things that matter in the public domain and the commons, among other things.

View of the Acropolis from the Roof of EMΣT

Title image: Claudia Comte, "How to Grow and Still Stay the Same Shape", Performance at ΕΜΣΤ