And the silence that follows

A conversation with Greek artist Janis Rafa on horses and their absence, on love and domination

“In the end, I think that’s what interests me most: that moment of being left alone with our creations. Without the animal present to justify them. Without the spectacle to distract us. Just the residue of power, of control, of desire – and the silence that follows”. That’s what Greek artist Janis Rafa (b. 1984) tells me as we sit in a café at the National Museum of Contemporary Art Athens (EMΣT). In mid-May, the museum opened a large-scale exhibition titled Why Look at Animals? A Case for the Rights of Non-Human Lives. Janis Rafa is not only a participant in this group project – just a little earlier, in April, she also opened a solo exhibition, We Betrayed the Horses, perhaps the most striking among all the solo shows currently on view at the museum.

“Janis Rafa’s artistic research employs different media from feature films to shorter videos, and from sculptures to drawings and text-based works. Her work focuses on the relationship between human and non-human animals, raising issues about seemingly contradictory schemes such as love and domination, seduction and consent, but also mortality and loss,” as noted in the catalogue essay by Daphne Vitali, who curated the entire exhibition and production process of We Betrayed the Horses. “Her films and installations often focus on the silent presence of animals, allowing them to become the leading force within her poetic and timeless compositions”.

Installation view of Janis Rafa’s solo exhibition We Betrayed the Horses, 2025. Produced by ΕΜΣΤ. Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Paris Tavitian

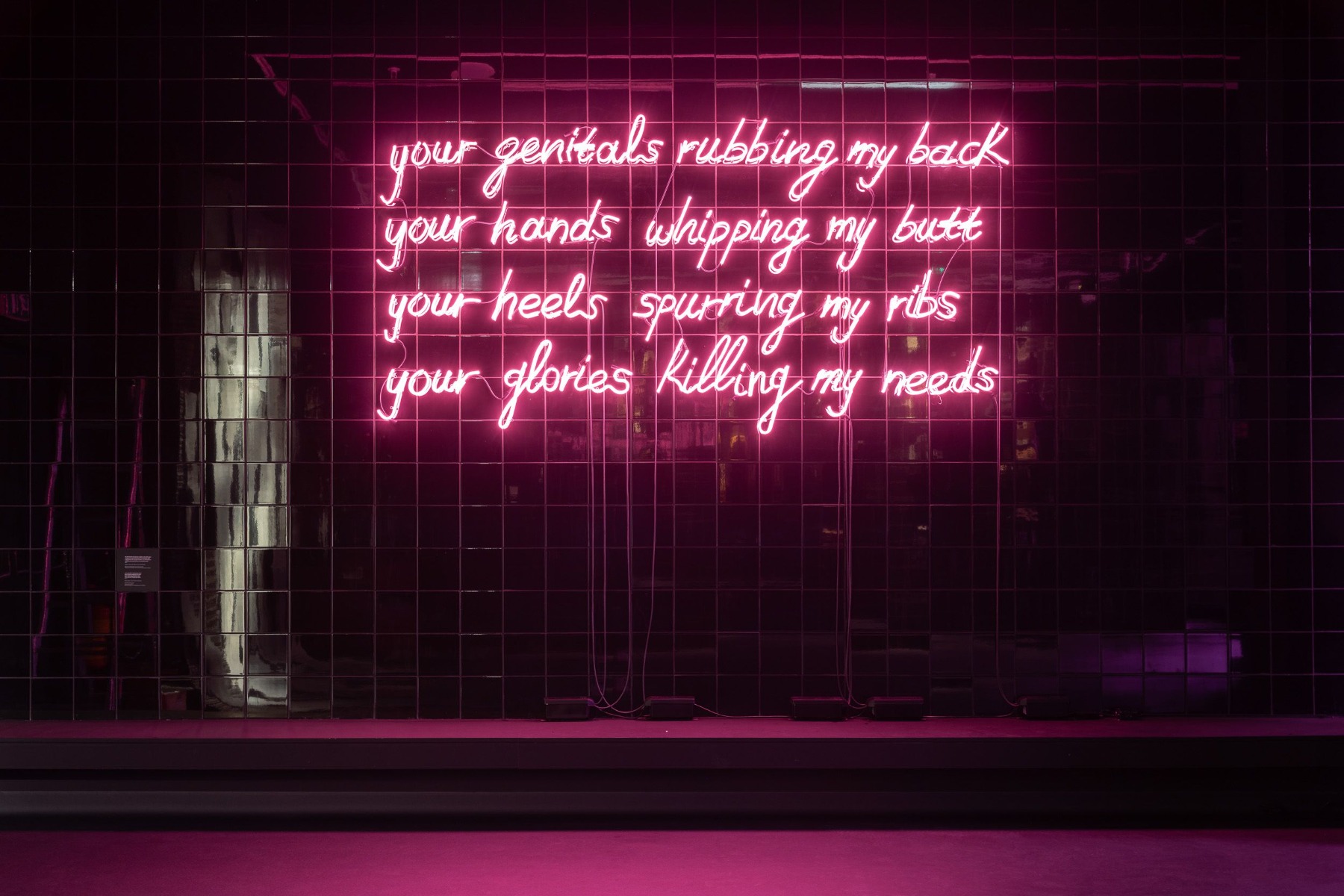

However, in this exhibition, the “silent presence” turns into a true silent absence. We find ourselves in a space covered in black tiles, where we are first greeted by a row of horse water troughs, followed by massive leather saddles hanging on the wall – worn, weathered, soaked with the sweat of both animals and their riders. On the adjacent wall, the dimly lit room is pierced by glowing purple neon letters arranged in four lines: “your genitals rubbing my back, your hands whipping my butt, your heels sparring my ribs, your glories killing my needs.”

The purple reflections of this inscription, curling across the black tiles, can be seen on all the other walls. To enter the next room, you must pass through a curtain made of horsehair – a fleeting, delicate touch that feels like an ephemeral caress from horses long vanished into oblivion. Beyond it awaits a video, filmed at a horse racing track abandoned for financial reasons—once the only one of its kind in Greece. “Rafa’s approach to filming – the characteristic darkness of her scenes, the absence of humans and animals alike, the constantly shifting lighting and specific angles that create the perception of a non-human perspective on the objects and the empty spaces that the camera pans over (not to mention the work’s particular soundscape) all ultimately serve to allude to an otherworldly place, forsaken and consigned to oblivion”.

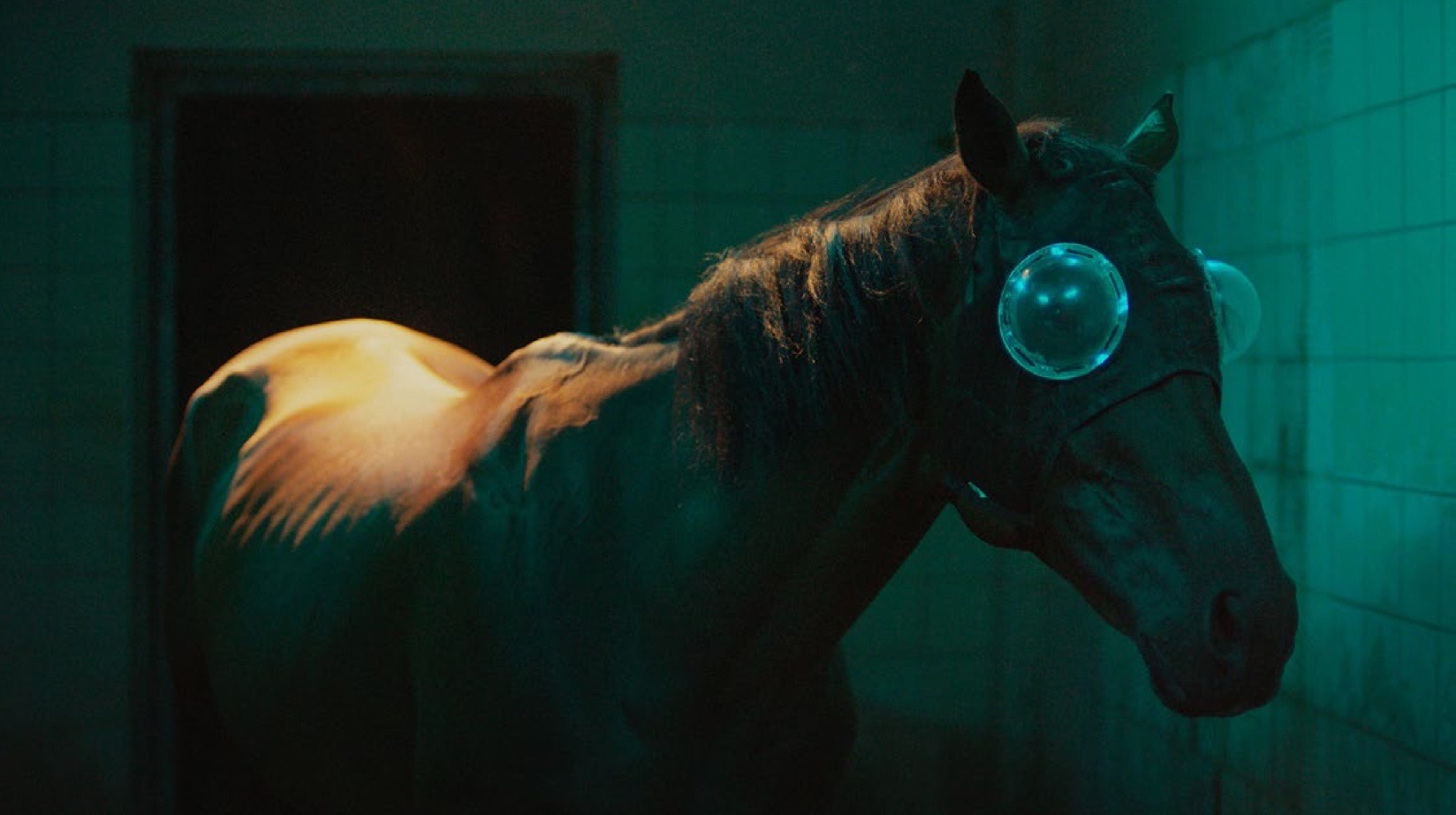

The work presented in the group exhibition also takes the form of video, but this time it's an impressive three-channel video installation titled The Space Between Your Tongue and Teeth, occupying an entire room. It was filmed in an enclosed space where racehorses are trained – forced to run on electric treadmills. The horses are visible, yet their eyes are covered with special devices. The powerful rhythm of image transitions across the three screens creates a compelling visual intensity. Human figures also appear – almost like demigods – caring for the animals, yet never loosening their grip on the reins of control.

Janis Rafa, The Space Between Your Tongue & Teeth (film still), 2023. Courtesy of the artist.

As I understand it, horses have been a subject of interest for you for quite some time. How did it all begin?

Animals have been central to my practice for many years. Whether in video or sculpture, they’ve always played a key role. But with horses, there is a deeper, more intimate reason behind it. I actually grew up with horses. I owned a horse and was involved in show jumping competitions in Greece. So there’s a very personal history tied to this subject – not only in terms of affection and memory, but also in how I gradually began to distance myself from those practices.

Over time, I came to understand that our relationship with animals – and horses in particular – often involves a profound misunderstanding. We claim to love them, we care for them, we feed them, we heal them, we host them in our lives and ask them to love us back. But actually, they are beings with different bodies, needs and desires than ours. We use their bodies for our own purposes, our own glory, our own pleasure. There's a certain trickery involved – we teach the animal to accept care as love, but that care often masks a deeper form of control and exploitation.

The horse, in this context, carries a kind of personal guilt for me. Perhaps it's not obvious, it can remain hidden – this autobiographical element – but it’s still there. And at the same time, it also points to a more universal guilt that I try to highlight through the work: this betrayal of another being.

The horse is also a powerful cultural icon – a symbol of elite, resilience, conquest, and human progress. Horses have played a key role in colonization – not just the colonization of land, but also of entire ecosystems. They were tools of empire, of expansion. They enabled the domination of both terrain and people. But in this exhibition, I was interested in reversing our usual perspective. Not looking at the horse as a symbol, but rather acknowledging it for what it truly is – a living, desiring being. This parallels the approach of the exhibition Why Look at Animals? as a whole, which doesn’t treat animals as metaphors or symbolic stand-ins, but tries to see them literally, as they are.

Installation view of Janis Rafa’s solo exhibition We Betrayed the Horses, 2025. Produced by ΕΜΣΤ. Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Paris Tavitian

But what differentiates your work, though, especially in your solo project We Betrayed the Horses is the emphasis on absence – the animal is no longer present.

It is an exhibition that speaks about the horse but through its absence. The body of the horse is not present – it appears only in archival footage within the video. This absence is powerful. It becomes even more pronounced through the objects I include – all of them used, worn, bearing traces of time and of trauma. Some of the saddles date back to the 1940s, 1920s – one even from the 1880s. They carry a history of bodies that once occupied them. There’s a kind of negative space around the mouthpiece or under the saddle, that tells a story of presence now gone. The absence of the horse in this work becomes not a void, but a presence in itself – a haunting presence, a space filled with memory, tension, and unresolved emotion.

It’s a space shaped by the absent body, and often reduced to its minimal dimensions – minimized for efficiency, for control, for profit. Just like the spaces we design for animals in captivity, in stables – it’s always about control and functionality: how to make them occupy the least space possible, how to structure them for optimal productivity, or how to feed our bodies through theirs.

Take the horse's mouth, for example. The shape and placement of the bits are designed to fit into a part of the mouth where there are no teeth. We invented the bit precisely to exploit this anatomical “negative space.”

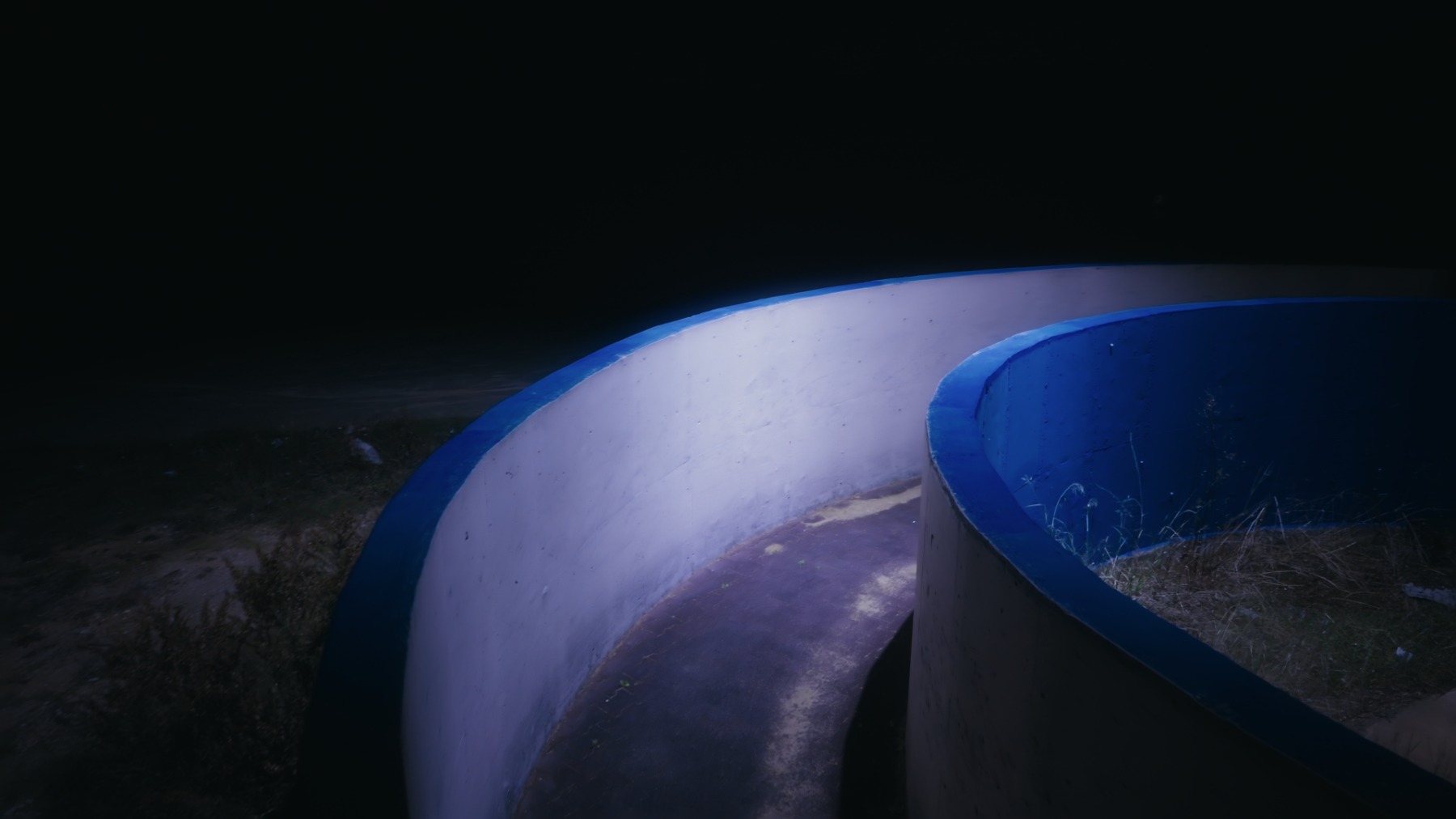

Janis Rafa, The Absence of your Body has Shaped the Spectacles of our Past

2025 (video still). Double-channel projection, 16:9, 5.1 surround, 12'35". Produced by ΕΜΣΤ. Courtesy of the artist

In the video work, which is a part of We Betrayed the Horses exhibition, we see an empty racetrack. It’s the only horse racing track that existed in Greece, and it closed a few months ago due to economic issues. Thankfully, it seems it will not reopen – at least not as a racing venue. I was able to get access to film there. Again, the animal is absent. In fact, both animals and humans are absent. What remains is light – the movement of light across abandoned spaces. It illuminates the structures where the animals once performed, and where humans once gathered to consume that performance as spectacle.

Yet, there’s another important layer in the work: the theme of non-consensual relationships. It explores the complexity of desire – the desire to dominate in order to please ourselves. We often say we "take care" of animals, but that care is conditional. We take care of the horse we own, but in exchange for taming and domination. This creates a kind of role-play – an involuntary performance that the animal must enter into, without consent.

In the BDSM culture role-play involves dominance, submission, and bodily violation. But in that context, these things are based on mutual consent. With horses, and with animals more broadly, this negotiation is impossible. The whips, saddles, reins become tools of non-consensual control, of the eternal “who’s on top”. There are also other works of mine that aren't part of this exhibition, but they explore similar themes – particularly around leaking, mouthing, and the mouth itself. Because it's a betrayed mouth, it's a mouth that is tricked, like the instincts of the animals are tricked in order for us to control them.

Installation view of Janis Rafa’s solo exhibition We Betrayed the Horses, 2025. Produced by ΕΜΣΤ. Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Paris Tavitian

At first glance, there’s a certain sensuality – something that may seem ‘sexy’ or ‘erotic’. Phrases like “your genitals rubbing my back” appear in the work. I like to lead the viewers with more sexualized or sexually charged kind of connotation. This misreading is essential here. For instance, the video work The Space Between Your Tongue and Teeth – the triptych which is a part of the group exhibition – very much plays in this direction. At first glance, it seems to present a spectacle of desire – a performance of friction between bodies. But then, it twists. As the viewer spends more time with it, there’s a shift in the translation of the work and its collateral meanings. The pleasurable, sexy spectacle begins to reveal itself as something entirely enforced, something imposed. What appears as desire is actually violence, born from a long anthropocentric, authoritarian, patriarchal history in which animals are seen only through their capacity to serve us. This is the real betrayal: the fundamental denial of autonomy, of agency, of mutuality.

Installation view of Janis Rafa’s solo exhibition We Betrayed the Horses, 2025. Produced by ΕΜΣΤ. Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Paris Tavitian

Can that betrayal ever be resolved?

It’s difficult to say. I don’t think it will disappear anytime soon – at least not for hundreds, maybe thousands of years. But there are gestures toward other ways of being with animals. Animal shelters, for example, are a powerful model. In those spaces, animals are not used or consumed – they are simply allowed to live, to grow old. The act of caring for an animal not for use, but for the sake of life itself, feels revolutionary in contrast to our historical relationships. The right to grow old if you are an animal is by itself a political act, a revolution.

But I want to be clear: this work is not about proposing solutions. It’s not a didactic or moralistic inquiry into how we should treat animals. The animal here is a negative space that allows us to reflect on ourselves, on the systems we've built, on our desires, our technologies, our hypocrisies. The mouth-bits, for example – each designed so specifically, so precisely, like jewellery. Each one engineered to interact with a particular instinct, a particular resistance, a particular muscle. The ingenuity is disturbing. It's a kind of archaeological footprint of control. A history of how we’ve shaped matter in order to shape behaviour.

When the animal is no longer there – perhaps extinct, or simply absent – we are left alone with all of this: the remnants of our inventiveness, our need to dominate, our mythologies of care. The empty racing track, for instance, becomes a kind of monument to that history. A loop of spectacle with no performer. A space built to suppress instinct and manufacture performance.

In the end, I think that’s what interests me most: that moment of being left alone with our creations. Without the animal present to justify them. Without the spectacle to distract us. Just the residue of power, of control, of desire – and the silence that follows.

Installation view of Janis Rafa’s solo exhibition We Betrayed the Horses, 2025. Produced by ΕΜΣΤ. Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Paris Tavitian

And a wall of used saddles…

Yes, they hold traces, imprints, a kind of haunting. This usedness carries a ghost-like presence. For me, there’s something profoundly moving in the way they retain a footprint of the bodies that once passed through them. Because when we talk about animals, we must remember we’re speaking of lives with different timescales – shorter lifespans, rotating ownership, functional purpose. A rider rides many horses in their lifetime. There’s a consumption of bodies involved. The saddles stay. The bodies do not. So what we’re left with is a material tribute – not only to the horses I personally rode, and the guilt I carry – but to a broader, more painful history of bodily erasure. Let’s not forget that saddles themselves are made out of bodies, of leather.

This exhibition is, in many ways, a tribute to the ‘performed’ horse – not the horse as it exists in itself, but as it exists through us, through our imaginaries. We don’t really know what a horse is, only what we’ve required it to perform for us: labour, beauty, obedience, strength. We have constructed a version of the horse under specific conditions – economic, aesthetic, colonial, patriarchal. So, if we attempt to deconstruct that ‘performed’ horse, what’s left? Saddles, bits, stable architecture. Taming. Tools of pleasure. Tools of domination. My interest is in exposing the perversion that defines our relationship to animals. A perversion not necessarily in the sexual sense, but in the structural sense: the perversion of power, the distortion of intimacy, the way domination becomes normalized.

Installation view of Janis Rafa’s solo exhibition We Betrayed the Horses, 2025. Produced by ΕΜΣΤ. Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Paris Tavitian

Does this perversion have also some sadistic connotations?

I think it's clear sadism, these power relations. We speak of pleasure, of bonding, of love. But these are one-sided. Consent is never really present. It’s always an anthropocentric illusion. Yes, but the horse loves me, we say. Look how it runs to me. Maybe it does. Maybe it runs because we feed it well, or treat it kindly. But that’s not the point. The power dynamics remain. It’s still about us. The horse, like the animal in general, is not granted full subjecthood – it is sculpted into a mirror for our desires, our ambitions, our narratives.

There’s also a broader question in this conversation about what happens when we stop using animals – when we stop exploiting them, producing them, orchestrating their lives and deaths. Some might say, “Well, then they wouldn’t exist.” But that argument – often made in defense of mass sterilization or even factory farming – is flawed. Take sterilizing stray cats in Greece, for example. Yes, it limits population, and it also reduces suffering – less disease, fewer roadkills. But at the same time, it's a human decision about which lives are allowed to exist and why. It’s the same with factory farming. If we stopped producing animals for food, many of those animals would simply never be born. But isn’t that better than birthing lives only to abuse and kill them? Every piece of meat on our plate carries a history – not just of death, but of rape. Of forced reproduction. These animals are not just killed – they’re violated into existence.

This brings me to another direction I’m exploring in my work – one that intersects with feminism and reproductive justice. If we are to talk seriously about feminism, about care, about bodies and consent, we must talk about the mothers of others. The female animals who are routinely abused, confined, inseminated, and drained – physically and symbolically. Animal politics cannot be separated from gender politics. They are fundamentally entwined.

Janis Rafa, The Absence of your Body has Shaped the Spectacles of our Past

2025 (video still). Double-channel projection, 16:9, 5.1 surround, 12'35". Produced by ΕΜΣΤ. Courtesy of the artist

Perhaps it’s meaningful that horses are probably the most beautiful creatures among those considered to be domestic animals.

Yes, the horse is a beautiful creature – perhaps even too beautiful for its own safety. There’s a mechanism of pleasure, of aesthetic admiration, that makes us exploit not only their physical bodies but also their image, their presence.

The whole world is based on a big misunderstanding, and we’re left trying to live inside that. There’s very little real space for imagining different conditions of being with animals. Shelters, perhaps, are one of the few exceptions. They are models of coexistence without use. But I often feel that I betray every principle I stand for when it comes to animals. I fail, every day. I use animals in my work, I pay these people that I don't want to be supportive of their practices. I buy saddles made of leather – the skin of another animal. There is continuous failure in my practice but I fail also in my personal life. I’m vegan myself, but I fail with my child. It’s not an easy road to find a space to relate to animals in the kind of positive way and in relation to the rights. There’s no basis of rights from which to even begin. We’re improvising ethics inside a structure built to fail them.

Installation view of Janis Rafa’s solo exhibition We Betrayed the Horses, 2025. Produced by ΕΜΣΤ. Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Paris Tavitian

Installation view of Janis Rafa’s solo exhibition We Betrayed the Horses, 2025. Produced by ΕΜΣΤ. Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Paris Tavitian

Still, what matters is that through your works and all others exposed now in EMST we begin to see this betrayal. I think that’s the most crucial thing art can do. Because most people don’t see it. They look at it and don’t see it.

And it goes beyond horses or animals. It’s also about relationships in general. About love, about intimacy, about partnership and parenthood. Because we love under particular terms and these terms are always very controlling, they are strongly role playing.

You mentioned in our talk that you owned a horse.

Yes, I owned a horse for many years. I didn’t come from a wealthy family, so it happened almost by chance. I became involved in horse riding, and eventually owned a horse. I trained, I competed, I believed I loved him. But I was also making his life miserable. It took me years to realize this. In the last 10 years of his life, I managed to give him a good life – to live among other horses, to come to the stable only to sleep and eat. I never rode again. But it was a slow, gradual disentangling from what seems to be a normality. Because to have a horse and not ride it is still considered weird, at least in Greece. Again, this is why I mention shelters – not as a utopia, but as a working model for being-with, without using.

Janis Rafa. Photo by Melitini Nikolaidi

What was the name of your horse?

Mentos. We were together for 23 years.