A Brief History of Change: An Interview with Penny Siopis

For Dear Life. A Retrospective, the first major museum retrospective in Europe of the work of Penny Siopis, is open at EMΣT until 12 January

It was this summer in Athens, at the opening of her solo exhibition at the National Museum of Contemporary Art (EMΣT), that I met the South African artist Penny Siopis. Her exhibition became part of the extensive programme WHAT IF WOMEN RULED THE WORLD? which is running for an entire year and presents a total of 18 solo exhibitions, installations, and projects, showcasing the work of 40 women artists. Penny’s works are displayed on the underground floor of the building, where you feel as though you are entering an entirely different reality and story. On the one hand, it’s a narrative familiar from news reports, articles, and films; on the other, it is tangible and wholly material.

Penny Siopis was born in 1953 into a family of Greek origin who had settled in South Africa after World War II. Her life and works, spanning different periods and series, tell the story of the country and the story of a woman living within it. A white woman who actively opposed apartheid. But it is also the story of her relationship with objects and materials, and the gradual realisation of her artistic path: "I’ve always been interested in this idea of transformation, where material substance is either becoming something new or disintegrating, in different ways representing change."

Her works are held in the collections of Tate Modern, London; Centre Pompidou, Paris; Moderna Museet, Stockholm; The Walther Collection, Neu-Ulm; Smithsonian National Museum of African Art, Washington, DC; and the Art Institute of Chicago, to name but a few.

Penny Siopis. For Dear Life. A Retrospective. Installation view at ΕΜΣΤ. Photo by Paris Tavitian

Penny herself is a very energetic, slender and friendly woman. We begin our conversation in a Greek restaurant the day before the opening and continue it next day on the museum’s terrace. We talk about how history and painting, films and reality (or perhaps realities in the plural) intertwine in her life. We keep talking while the museum is full of guests and finish only when we find ourselves its sole remaining visitors. By then, the warm Athenian night has fully descended, and we make our way out, descending a series of escalators completely alone. Somehow it seems that such slightly unreal moments are an everyday reality for Penny Siopis.

Penny Siopis. Obscure White Messenger. 2010. Single-channel digital video, 15’ 7" © Penny Siopis. Courtesy of the artist and Stevenson, Cape Town, Johannesburg and Amsterdam

How do you feel, as someone born into a Greek family, when you come back to Greece? Do you still feel a sense of 'Greekness' within you?

I do, I really do. It’s interesting because I haven’t lived in Greece, and in many ways, I’m not entirely Greek, but I grew up with a lot of Greek experiences. I’ve traveled here and spent holidays, but Greece has always been more of an imagined place for me. At the same time, I’m also South African, so there’s a sense of having two identities, but they don’t feel in conflict with each other. Maybe that’s because Greek culture is quite diasporic; many Greeks live around the world. As a child, there are a lot of sensory memories that shape your identity. I remember so many things typical of Greek culture – wonderful Greek food, Greek music. I heard it all the time. One of my earliest memories is listening to bouzouki music because my parents would play old records. I grew up surrounded by Greek culture through sound, food, and hearing my father speak a lot of Greek. So Greek culture was both familiar and a bit foreign to me.

Penny Siopis. For Dear Life. A Retrospective. Installation view at ΕΜΣΤ. Photo by Paris Tavitian

Katerina Gregos mentioned in her story about you that your mother used to make cakes...

Yes, my parents owned a bakery, which is a very Greek thing to do. We lived in a small desert town in northern South Africa, and the bakery was on the same property as the house. The bakers who worked there lived on the property but in the section adjacent to the bakery building. It was unusual for that time, in the late '50s and '60s, with the laws of separate development that governed apartheid, for black and white people to live on the same property.

My mother would often bring cakes from the bakery into the home dining area to ice them. I would watch her while listening to Greek music in the background, my father chatting with his Greek friends, and the bakers singing as they made bread. It was a fascinating blend of sounds and cultures all coming together. I was captivated by how, under my mother’s skillful hand a lump of icing could be turned into a beautiful decorative form. That definitely influenced how I came to think about the relationship between formless matter and form – and the idea of material transformation more generally.

That comes through in my 'Сake paintings.' Of course, I use oil paint instead of icing, but there’s a similar process at play. When I first made those paintings, they were considered quite radical. They were meant to age and crack, like skin or bodies, rather than be preserved perfectly. So, growing up in that household, surrounded by all these rich sensory experiences, shaped the way I view art and materiality.

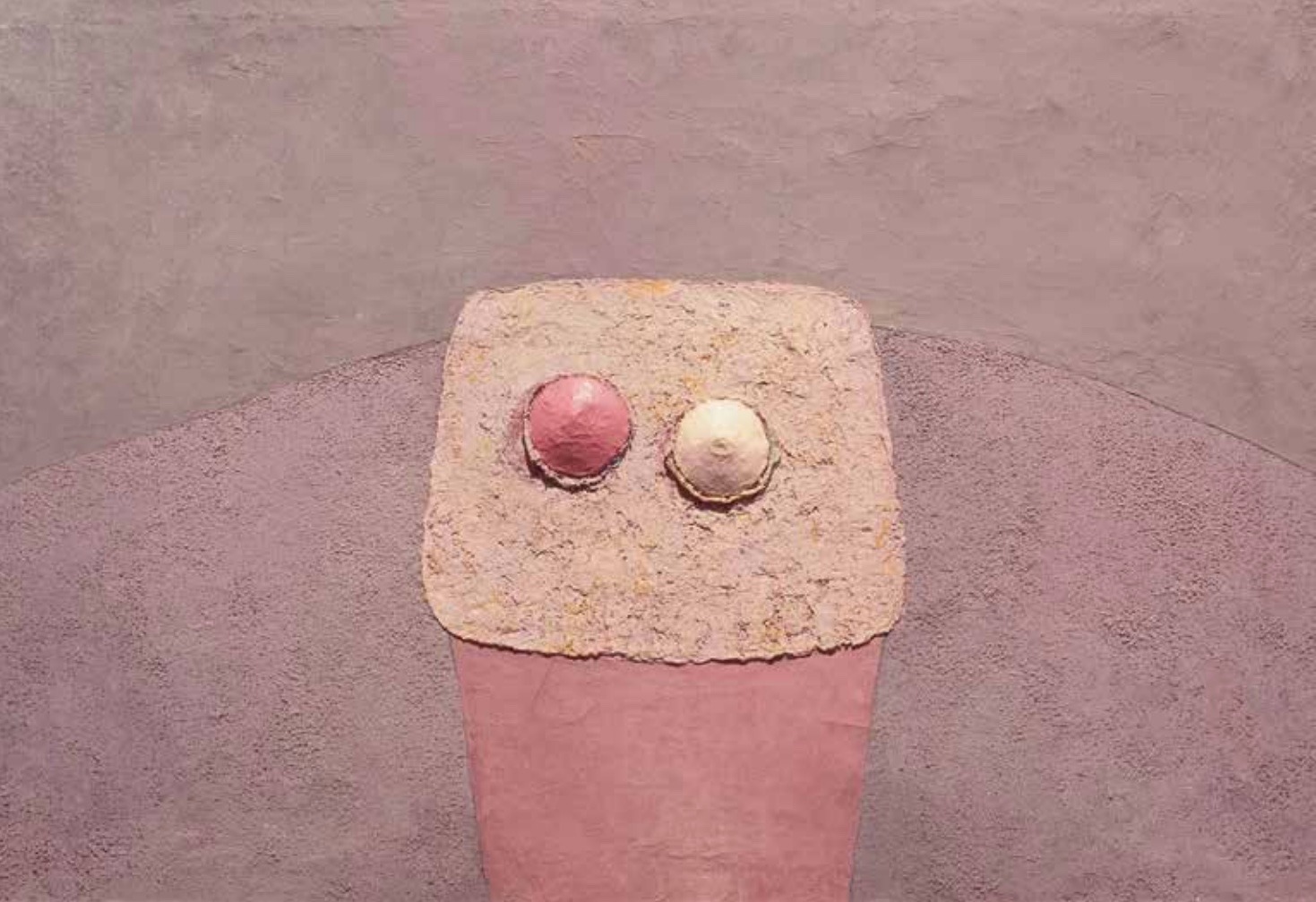

Penny Siopis. Queen Cakes. 1982. Oil on canvas. 90 x 130 cm © Penny Siopis. Courtesy of the artist and Stevenson, Cape Town, Johannesburg and Amsterdam

But did your mother like these 'Сake paintings'?

I don't know, she never said. But I don't think so, because they're quite sexualized, you know. I mean, she didn’t actively dislike them. I think this was because, as they started out as references to cakes, there’s this understanding that they would be associative rather than explicit. Like the work Queen Cakes that looks a bit like breasts. It doesn’t take much imagination, though, to associate their forms with sexual organs.

I was also interested in this association and the sensuality of oil paint and aging from an art history perspective. When people say, 'Oh, she's no oil painting,' it means she’s not considered conventionally beautiful. What they’re really talking about is the stereotype of women that has been historically produced through painting – women as the subject, rather than the artist. Traditional oil paintings of women that became conventions, starting with portraits and evolving into the female nude in Western art history. These paintings typically have very smooth surfaces, but if you look closely, they often develop cracks over time. Museums are always trying to hide or repair these cracks, preserving the idealized image.

When I used oil paint in my work, I wanted it to be excessive, to represent not just a means of depicting the body, but the body itself – imperfect, aging, full of texture, and disruptive. So, in that sense, I think my mother understood that my work was also a way of engaging with Western art history and challenging its conventions.

Penny Siopis. For Dear Life. A Retrospective. Installation view at ΕΜΣΤ. Photo by Paris Tavitian

Penny Siopis. Ambush. 2008. Ink and glue on canvas, 200 x 250 cm. Collection Skinner, Johannesburg © Penny Siopis. Courtesy of the artist and Stevenson, Cape Town, Johannesburg and Amsterdam

Another set of materials that is very meaningful to you is glue and ink.

I’ve always been interested in this idea of transformation, where material substance is either becoming something new or disintegrating, in different ways representing change, and the glue and ink paintings works do this most clearly. Change is constantly happening in our lives, whether it’s social, political, or related to aging. History is often depicted as subject, but it's not necessarily actualized as experiences of change in the now. Yeah, we grow old, you know, – and my 'cake paintings' are basically bodies that change – and we decay. But I'm interested in also this, how the materiality can be almost autonomous, do its own thing, as well as being the substance that hooks something of a subject into it, because of the way we humans are compelled to narrate the world, to always ‘read’ significance into matter. Over the years I've been painting, my thoughts have shifted to embracing more strongly thinking about the agency of the medium itself. How does the medium act?

I had started to work with glue as an adhesive to apply paper collage elements to a surface on top of which I could apply oil paint. This was in the eighties. Gradually, the glue began to take on a new role, especially in my 'Shame paintings', where it became a more expressive surface, acting somewhat like a skin. Eventually, it developed its own form and became an autonomous medium.

It all comes down to how the glue behaves when I work with large stretched canvases on the ground. The glue is white as it comes out of the cannister. As the glue dries, and it interacts with the ink I drop into it, it changes to become transparent and slowly reveals the shapes of the chemical changes that have happened under its wet white ‘skin’. The environmental conditions affect the drying process and help shape the physical changes. Gravity plays a role, pulling the glue and ink into the dips of the canvas as they flow and settle. This transformation of the medium led me to cultivate a philosophy centred around material agency, movement, change, and openness. And I came, in part, to refer to this process of as 'painting blind’, because of the demastering effect it enabled. Typically, when you paint, a key aspect is that you can see what you're doing. You put down a mark in relation to a mark you’ve made, then another, and so on. However, when I paint with glue and ink, there is no mark making in this more conventional sense of painting, because the glue, which is white conceals or disguises the stains made by the ink. The process works horizontally; as I mentioned, gravity shapes the effect, but the air also plays a role in drying it. Working horizontally is of course also a conceptual challenge to the more conventional vertical axis in which we usually make and see paintings.

All these elements are at play, along with the gestures of my body. As the white glue slowly dries, it reveals the movements that occurred during the interaction of all the materials. Essentially, it captures and freezes that movement as it becomes transparent. The glue itself changes, unveiling the transformations happening within its own 'body. It sounds very abstract, maybe, and somewhat formalist, but it really stems from the idea of materiality having its own agency, rather than merely following the classical notion that artists control and possess their medium. For me, the philosophy is much more relational; there's a greater openness to process as concept as well as form. I'm interested in surrendering to that process.

Once the pieces are dry, I lean them against the wall, and the way we perceive them can begin to suggest an image. I see these emerging images as forms of becoming – they're constantly evolving. I call these forms ‘potential images’. My approach is to simply drop the ink into the glue, and once it's dry, engage with The glue and ink mix has created the visual residue. that’s emerged. Often, I rotate the piece – turning it this way and that – exploring its potential. This process embodies the idea of randomness, that is not entirely random. It parallels my films, where I find reels of old 8mm footage in little reels scattered in flea markets and thrift stores. I buy the reels without knowing what’s on them. Similarly, when I work with the glue, and can't see what I'm doing until the glue has dried transparent. It is not completely clear in all areas of the canvas. Parts are thick and more opaque. There is a revelation of sorts in what happens for me when I witness the material change, a process I actually link to ideas of opacity philosophically.

After I acquire these film reels, I take them to be digitized. Only then do I discover the content. From sequences of that old found footage, I craft something new with my films. This creates a constant tension between experience of what is given – what's around us – and the nature of the material itself. Whether it's celluloid, glue, ink, or oil paint, what these materials do is not so different to the behaviour of the cake icing of my mother. They all undergo a transformation into something ‘other’, that I see as becoming form in different ways.

Penny Siopis. For Dear Life. 2020. Glue and ink on canvas.190 x 90 cm. Private Collection, Cape Town © Penny Siopis. Courtesy of the artist and Stevenson, Cape Town, Johannesburg and Amsterdam

But you also work with real objects – things that already possess a concrete form. For example, in your Will (1997- ), “a monumental, autobiographical conceptual work-in-progress which will only be completed on the artist’s death. As part of this work, Siopis bequeaths a diverse collection of objects to beneficiaries of her choice: friends, family, collaborators from all over the globe. Will is an installation that includes over 700 objects that provide insight into the artist’s collecting habits and interests – artistic and vernacular – but also into her own personal history and experience, rooted in its own particular time, place and circumstances”, as it’s written in the curatorial text.

Yes, they already have concrete form but their roles in the world are continually changing and this affects how we perceive their form. Their ‘character’ is shaped in relation to the other objects around them in the world and the emotional attachments enabled. In Will each is part of a corpus which will be dispersed when I die, and will scatter across the globe to a new, unknown context. Will emerged out of Charmed Lives, a huge installation of found objects clustered together in an organic form that also kept changing. I was interested in the idea of mass versus particularity and reference and materiality, exploring where this tension lies. The installation feels like a massive organism. But when you take something out, the object asks for a certain kind of narrative. Which can change depending on how it is framed – some kind of story emerges.

Each object has its own story, and I'm fascinated by the fact that the stories, like the footage I collect, have been shaped before me. I'm not the originator of the story tied to that object; in fact, I often don’t know what its origin, its story is. In this way, each object holds, not only a history, but a presence that I inherit. Also each object has a material body that is very distinctive, whether it's plastic, hair, powder, or something else. Each one possesses its own unique character, almost like a character in a story.

What strikes me is the fact that, because each of these objects in Will has been assigned to someone in the world, none is truly mine. When I die, each will be dispersed across the globe. I'm intrigued by the idea of distributed personhood. We don’t have clear outlines around us that separate us from our environment, and similarly, the objects don’t have outlines either. They exist only within their collective sense of being. Each object is part of a larger organism – so far, there are 700 of them. Each has its distinctive character within this bigger whole. And they are not considered art in a traditional sense. But this is likely to change when I die, and then, the fact that each is only a part of a whole, might complicate its identity as a single entity. Beneficiaries might want to try to locate some of the other objects after dispersal, so as to give their bequest something of a ‘life’ it once had in the community of things of which they were part in a larger body. So, in a way, it reflects a sense of endlessness. If you receive something after I die, you might wonder, 'What do I do with this now? Do I keep it? Do I throw it away? Do I give it to someone else?' It creates a never-ending sense of process, really. It’s a very simple concept because it’s human-scale, and intimate; it’s not industrial. It relies on the involvement of other people. We don’t even know if it qualifies as work because it lacks clear boundaries, physical and conceptual. If you decide to throw something away, it could end up in a landfill.

Penny Siopis. For Dear Life. For Dear Life. A Retrospective. Installation view at ΕΜΣΤ. Photo by Paris Tavitian

Penny Siopis. For Dear Life. A Retrospective. Installation view at ΕΜΣΤ. Photo by Paris Tavitian

But through the way you choose these objects, I, as a viewer, feel that I can sense your personality in a very concentrated way.

Oh, that's great.

Because the choice is very personal.

Yes, it is very personal. And you know what? It's interesting you say that, because I’m very aware of ‘the voice’ of the object – however a voice is constituted, which for me is suggestive rather than actual. In my films, there's always the first person voice as text. As a viewer, you have to read the voice into being. It's active always from the viewers perspective. You might wonder, 'Who is this person speaking?' As we read, our internal voice, the voice in the head, shapes the story as well. In the films, the footage generally doesn't align with the text; it’s often arbitrary. The text hooks the contingency into narrative. It creates a sense of motivation and connection.

When you mentioned that objects possess a certain particularity, I completely agree. They are much like individuals within a crowd. While we see a mass of people, each person has their own unique consciousness. In the films, this individuality is conveyed through the first-person perspective. When viewers engage with it, they might connect this personal narrative with the ‘real’ objects of Will, which are described in the third person. Painting, on the other hand, uses a different language altogether. In the 'Shame paintings', for instance, there is text, words made from rubber stamps. These words, often cliches, are combined with more visceral, traumatic imagery.The text becomes bodily. This juxtaposition changes the meaning of both text and image, transforming the work from something you might find on an ‘innocent’ greeting card into something much more disturbing.

So it's interesting when you mention picking up on the personality in the work – I like that. I love the idea of building character through particularities. I’m not a writer, though I enjoy writing the texts for my films and the little stories for the Will objects. What fascinates me about writing is that, unlike visual art, you're constructing a potential mental image, and the reader invents their own forms and interpretation too. With visual art, I think people often believe that everything is contained within the representation itself. I prefer to keep an elastic relationship with meaning, while still being committed to a certain kind of particularity of an object, a material process, and my own sense of its resonance.

Penny Siopis. Charmed Lives. Installation view at ΕΜΣΤ. Photo by Paris Tavitian

From these found objects you can also read a lot about history of South Africa. I’m thinking about your work “Charmed Lives” (1998-99), presented here in EMΣT. It’s like a wave of history, materialised it things. And it’s also in a way your history as a person…

I grew up under apartheid, and lived through the struggle against apartheid of which I was part, like many white people were. So, there were all these complexities about living in a situation with entangled intimate relationships with larger political processes which were beyond your control in one way because you were born into it. But in another way, you could actively resist it, do what you could do, by using your privileged position and skills. For me raising consciousness through educational institutions was part of this resistance. Many people fought for change in different ways.

When I was a child, Agatha, a black woman looked after me. I had a deeply intimate and loving relationship with her. But the larger system of apartheid prevented children from developing or continuing those kinds of relationships. As a small child, you wonder about that because small children don’t have a sense of prejudice; they just love the person who cares for them. Then I went to school, and there were only white kids. That felt strange. Later, at university, which was essentially white, I’d become involved in student politics, but still in the protected space of a university.

When I went to England to study, I had a completely different experience of politics. In South Africa, it had always been about race, the politics of the country, and the struggle for national liberation. In England, the focus was on Marxist aesthetics and class struggle – which I hadn't thought about much before. There, I also encountered feminism and gender issues in a new way. So when I returned to South Africa, my views on gender, class, and politics had changed, expanded. And that’s also when I made the 'Сake paintings.' Around that time, social unrest in South Africa was gaining momentum. I moved to Johannesburg and started teaching at Wits University which had a strong culture of political activism. We were all deeply involved in changing curricula, and adapting to the extreme state repression and unrest that surrounded us. All of that inevitably found its way into my work, though not in the form of directly painted images of those events.

It just becomes a kind of presence in the work, like a large body made up of historical moments. Having lived through all these histories, I think that naturally lends a sense of complexity to what I create. For instance, some of the objects in Charmed Lives belonged to my partner, who, like all white boys in South Africa during apartheid, had no choice but to be part of the military. They were conscripted as schoolchildren as soon as their names were registered in school. It was a tragic situation. Parents were conflicted. Some families with resources would leave the country. Others would try to keep their kids in university as long as possible, but after three or four years, even that became unsustainable. It was a difficult and painful reality to navigate personally, not least because of the consciousness of the larger pain of the disenfranchised communities under apartheid.

It was essentially a civil war. There was military action on the borders of the country, in Namibia and Anglola and later in the townships. Many were dehumanized as they dehumanized others. Eventually, people began resisting, joining the anti-conscription campaign, but it was a slow process, and some were imprisoned for refusing to serve. I remember when I was pregnant with my son in 1988, people would often ask, "Are you having a boy?" And I was. Then they'd ask, "What are you going to do? Are you going to leave the country?" – because having a boy meant he could eventually be conscripted.

All of that – a mix of personal, public, and collective narratives – became part of the ethos of living in South Africa.

Penny Siopis. Charmed Lives. 1998-99 (detail). Installation of found objects.

Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Mar Efstathiadi

And Charmed Lives is a very dramatical a multi-layered work itself.

It's difficult sometimes. People say to me, "Well, you know, your work is so political." And it is. But I was living in that environment up until 1994, a space that was inherently political in both action and words. Nobody could escape it. Everything was political. If you were living as a white person, separated from black people, that was political. You might not have chosen that, but it was the social and legal system you lived in, and that was profoundly wrong.

That kind of reality can't help but affect an artist’s way of making. It shapes you. And then there are all the questions around gender, which is a different narrative. Under apartheid, the primary focus was on the national liberation, the struggle to dismantle apartheid, so everything was centred around race, and gender issues were often sidelined. Questions around gender put on the back burner. It was even acknowledged by many gender activists at the time. The understanding was, "Yes, it’s a problem, but we’ll address it once we’ve achieved national liberation." Immediately after apartheid, even during the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, there were some discussions around gender-based violations, particularly those affecting women and children. But there wasn’t much attention given to it. There was apparently no space for it. It should have been addressed – it's wrong that it wasn’t – but at the time, it was understandable.

My interest in gender issues emerged when I returned from England, where I had developed a consciousness around feminism and feminist art aesthetics. When I started teaching at Wits, I also developed a feminist art course. Gender and sexuality questions were always present in my work, though they weren’t foregrounded enough in the media during apartheid due to the focus on the broader national struggle.

Penny Siopis. Pinky Pinky: Blue Eyes. 2002. Oil and found objects on canvas,

41 x 50 cm. Private collection of Teresa Lizamore, Johannesburg © Penny Siopis. Courtesy of the artist and Stevenson, Cape Town, Johannesburg and Amsterdam

You work a lot with material objects, but I think that in the series of paintings called ‘Pinky Pinky’, you are giving materiality to something invisible.

Yeah, exactly. It’s like something visceral that’s also spectral. If you think of the Pinky on the cover of the catalogue for the exhibition, it’s essentially a pink field, an articulated surface of pink color, with two eyes. They’re fake eyes, and the paint takes on a fleshy quality. However, it’s the viewer who perceives the gestalt of the face and sees it in that way. Pinky Pinky is an entirely invented creature of the imagination. It doesn’t have a pictorial reference; rather, it has a narrative – a story about this ‘creature’ Pinky Pinky, which is an urban legend. This story is constantly woven, continually being created.

What I did was ask school children, 'Who is Pinky Pinky?' Each person would tell me different things: 'Pinky Pinky is this,' or 'Pinky Pinky is hairy.' These verbal stories lingered in my mind, and each of those paintings is a manifestation of this creature of the imagination – this ghost that doesn’t exist, yet somehow does exist.

Penny Siopis. For Dear Life. A Retrospective. Installation view at ΕΜΣΤ. Photo by Paris Tavitian

Is it a ghost of the city?

No, it has evolved; it has a narrative. Anthropologists might say that this character, this urban legend, developed when rural people came to work in the mines in the city of Johannesburg and its surrounds in the fifties and sixties. That’s why it has a distinctly urban quality. Apparently – though I say this with some correction – one of the anthropological pieces I read suggested that it’s built on a traditional myth about a scary creature that is sexualized, often depicted as a small man with a big penis. This concept of scale is interesting because it relates to what called a Tokoloshe. The Tokoloshe in South Africa is this little man who stands at the door of your room. That’s why it’s customary to put salt on the ground, to keep him at a distance.

I think the legend reflects an anxiety about displacement. For instance, the men who were moved from their rural villages and communities to the cities to become laborers for the mines, lived in compounds, which were boarding houses, but these settings were not sympathetic – rather, they were dehumanizing.

The idea is that the character of Pinky Pinky emerged from the foundations of this more traditional myth, becoming associated with the fear of coming to the city, not fitting in, and suffering hardships. Pinky Pinky became more prominent as a story told by schoolchildren, both girls and boys. With the demise of apartheid, schools were integrated, but it was a slow process. During the pre-adolescent and adolescent years was when Pinky Pinky emerged. Children’s minds are particularly fertile, and they often create stories or myths to cope with feelings of insecurity. The future was very uncertain immediately after apartheid, and the children were the ones who had to face that uncertainty.

First, these kids at school experienced a sudden integration. This was significant because, in addition to racial, integration it involved bringing together many different cultures and languages in one class room. Although English was the dominant lingua franca, many cultural practices, including ‘white’ western practices, could feel foreign, depending on your background. This created a real hybrid environment, a blend of histories and myths creating fertile ground for stories encompassing social issues of the day, explaining the anxieties surrounding this coming together and the uncertainties that accompanied it.

The name ‘Pinky Pinky’ could also represent a metaphor for whiteness, as many of the fears were tied to residual white power. However, pink also evokes the idea of something underneath the skin; it is fleshy and lacks a definitive colour. Pink is an indeterminate hue, which adds to its complexity. Unlike the Tokoloshe, which is typically depicted as a male figure with exaggerated physical traits, Pinky Pinky defies easy categorization. Its gender and species remain ambiguous – whether it is human or animal is unclear. This in-between quality makes it even more unsettling because it cannot be easily defined or pinned down.

This figure, this character, was portrayed as a rapist who could assault children, scratch their faces, and yet remain invisible. There was a significant narrative surrounding this indeterminate creature in terms of colour, race, gender, and species – an entity that inhabited school spaces, terrifying and terrorizing the children. As a myth, Pinky Pinky serves as an allegory for the larger culture undergoing radical social transition. While kids today may not speak about Pinky Pinky as much, those from that generation, now grown up, all know of it. It’s quite extraordinary.

The realization of this myth in my Pinky paintings was also intriguing to me. Initially, I used a ‘flesh colour’ manufactured in oil paint, which isn’t commonly used anymore. At that time, this colour was regarded as a sort of dirty pink and was associated with the depiction of white skins. It was a actually a western conceit for universal flesh colour. There was an element of irony in the choice of paint colour.

Penny Siopis. Who is Pinky Pinky? 2002. Oil and found objects on canvas, 152 x 91 cm.

Private collection of Teresa Lizamore, Johannesburg © Penny Siopis. Courtesy of the artist and Stevenson, Cape Town, Johannesburg and Amsterdam

It's a lot of different contexts in just one mythological figure.

Yes.

But for me, it was really something which is around us, probably dangerous. But invisible.

It's pretty invisible, yet it looks at you. This uncanny quality is fascinating. In the classic Freudian sense, when you recognize something that looks back at you, it becomes uncanny. Pinky Pinky resonates deeply with people. While it garners interest abroad, those audiences often see it in a much larger context – reflecting a global anxiety about change and the invisible threats around us, like global warming. These themes invoke a sense of monstrous uncertainty.

However, in South Africa, people appreciate it simply as the story of Pinky Pinky. It's curious how this character can transcend boundaries and take on different meanings depending on the audience. It’s quite a mobile character.

Penny Siopis. Shame. 2021. (detail). Installation | 182 paintings. Mirror paint, oil, enamel, glue, watercolour, paper varnish and found objects on paper © Penny Siopis. Courtesy of the artist and Stevenson, Cape Town, Johannesburg and Amsterdam

It's indeed something universal. My wife, during her childhood, believed that under her bed there was a samurai with two swords. Whenever she got out of bed, she had to jump to avoid getting her legs cut off.

Children's imaginations are amazing because they're built on something real – often fear. Part of learning to be a child, or simply living in the world, involves understanding the consequences of actions. You learn quickly, for example, that touching something hot will hurt. These early experiences with the world teach children their own limits and boundaries, and they develop a fear of those boundaries being broken. I believe this awareness of vulnerability happens at a very young age, even before they fully grasp the fears they're fed later on. It comes from their own sense of being fragile in a world they don't fully understand. Vulnerability is closely tied to the idea of openness. We often talk about wanting things to be open, but when things are truly open, they are also deeply vulnerable, which requires a great deal of trust.

And with the glue and ink paintings, when I talk about surrendering to them, it involves a lot of trust in the process. If I approached painting in a more conventional way, I wouldn't want to risk 'messing up' a canvas. I wouldn’t be demonstrating control or mastery over the medium, as traditional painters might. Instead, I'm allowing the materials to lead, rather than imposing my will onto the canvas. I think that vulnerability is a thread that runs through much of my work—whether it's human vulnerability, animal vulnerability, or even the vulnerability of the planet. These may seem like big, abstract concepts, but they’re present in our everyday lives. Everyone feels that sense of fragility.

For example, with my 'Shame' series, I did extensive research and reflection on shame. I was invited to do a project at the Freud Museum, the installation marking the centenary of Freud’s Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality publication. That led me to delve deeper into shame, both on a social and personal level. There’s a clear convergence between social shame and psychic shame, but ultimately, the psychological and the social are deeply intertwined.

In South Africa, there was a kind of national shame, which I believe other countries experience too, but it was particularly palpable. This national shame was demonstrated in various ways, perhaps most publicly during the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. The TRC, while intended for healing, also became a kind of public spectacle, dramatizing the shame of the nation. However, I don't see shame as purely toxic. Shame can also be productive in shaping subjectivities. If we embrace it, acknowledging that shame is something we all experience, it can become a foundation for change and the grounds for empathy.

This belief is partly rooted in my own experience as a child. I remember witnessing something that I didn’t want to see – an incident of a little boy being exposed and shamed. At that age, I didn't have the vocabulary to describe what I was feeling, but I was deeply upset for him. It wasn’t that I had been told it was wrong or that someone explained the situation to me, but I felt this strong, almost overwhelming empathy for him. And that memory is still vivid for me, a powerful reminder of how deeply shame and empathy can be connected, even in childhood.

I wonder if this is how shame works: as adults, when we feel shame, it often links back to earlier childhood moments. Even if we weren’t directly shamed as children, we experienced situations that made us feel anxious, unsure of what to do with the emotions we had – for someone else, or even for an animal. And in those moments, maybe we didn’t act the way we felt we should have. I think about that boy I saw being bullied and how I, as a little girl, stood there witnessing it. Should I have run to help him? It’s that helplessness, the uncertainty of what to do, that lingers.

In my 'Shame' paintings, you’ll notice the figures are often distorted – small figures, but a the small format, potentially larger, with strange proportions and scales. I think that’s because we can’t really pinpoint what triggers our sense of shame. It’s a deeply visceral, almost primal feeling, something we experience before guilt, as many theorists agree. It’s rooted in the body, in the way we become aware of being seen. When I read psychoanalytic theory, especially about shame, there’s often this idea that a child’s first experience of it isn’t necessarily labelled as shame, but it’s a sense of exposure – of not being held or cared for in the way they need. Of not experiencing the loving glint in the mother, or care-giver’s eye. It’s that vulnerable feeling of being looked at without protection, of being seen in a way that leaves us open and raw.

So, if a child doesn’t sense the warm glint in the eye of the mother, or the caregiver – the person who is supposed to love them – and feels nothing in those eyes, it’s not necessarily the beginning of shame, but it could be a deep sense of loss, a loss of connection, and a feeling of exposure. I think if you’re not connected to someone, you can feel exposed. For example, we can be completely vulnerable when making love, but we don't necessarily feel ashamed, because we are connected. The shame comes when there's a sense of disconnection – a lack of deep emotional connection.

I suppose that’s why it traces back to early childhood, to those moments of being looked at, or not looked, with by an unsympathetic eye. If a child is gazed upon with indifference or harshness, it creates a sense of vulnerability and exposure. That’s where the early experiences of shame can begin. But I’m interested in shame because it’s this elusive feeling we can’t fully define, yet we all know it. It’s deeply human, and it connects us. While we might not always label it as shame, that visceral emotion is something universally felt. What’s also fascinating is how people feel the need to fight shame, to cleanse themselves of it, as if it’s something they can wash away. But I don’t think you can ever cleanse yourself of shame – it’s an intrinsic part of the human condition. It’s something we live with and, in some ways, it shapes who we are.

Penny Siopis. For Dear Life. A Retrospective. Installation view at ΕΜΣΤ. Photo by Paris Tavitian

And it means you are alive.

Yes, it does. And you're constantly reengaging your own values and emotions. We witness something shocking, and that initial shock can be the beginning of potential shame. It’s just a gut reaction, like when I see someone involved in a car accident – it’s got nothing to do with me directly, but I’m witnessing them in a vulnerable state. They’re exposed, not only because they’re injured and need help, but in other ways too. Their skirt might be lifted, their leg might be broken. It’s a tragic image, and we often struggle to process it.

This brings me to a broader question, one that Katerina raised today – a good one. People often ask: What gives you the right to make images of other people’s lives or cultures? It’s a political question, and I understand why it’s asked. But in reality, it feels odd to suggest that we can’t connect across differences, or that identity is such a thoroughly self-contained entity that there is no scope for identification without violation. There are always power relations involved and it’s imperative to be sensitive to these relations, which involves questioning your own subject position. But being in the world, for me, especially as an artist, means being with others.

If I can’t imagine someone else's pain, and give it some kind of form – if I have to first determine if they’re white or from a different culture before I can empathize – then we've missed the point of human connection. I get the concern more when it’s about blatant cultural appropriation, but there's a difference between appropriating a culture and responding to the universal experience of suffering.

But what you said about shame is also somehow connected to what you were speaking about regarding changes. If you feel shame, it means that you are probably changing.

I mean, I don't think Donald Trump, for instance, feels any shame. He certainly doesn't embrace it. He might be driven by shame – maybe unconsciously – to blame others, and take revenge, like, 'I’m going to beat somebody up,' or whatever. But he's not dealing with the shame; he's not embracing it or seeing any insight in it. He’s not self-reflecting. It’s just reacting – like fighting. 'You beat my girlfriend up, I’m going to smash your face in' – that kind of attitude. And it often centres around sexual issues, too, around possessing women’s bodies. You still hear it today: 'They raped our women, so we’ll retaliate.' Old notions of shame as the opposite of honour!

I think shame is still a big issue, constantly engaged according to the concerns of the day. It’s interesting to me, that I revisited shame in my work more recently. I made the paintings between 2002 and 2005. And then I made the little film Shadow Shame Again, which was more specifically focused on gender-based violence today. It’s been interesting how shame came up very strongly in the #MeToo movement as a form of vulnerability which, if faced, could be empowering, even liberatory, to women in normative contexts where shame is only toxic, situations that operate to keep women in their place. Now you don’t have to feel ashamed about feeling shame.

I remember someone asking, 'How can you be looking at shame and not just critiquing it as a toxic emotion?' Well, first of all, I don’t think emotions themselves are toxic. We don’t even really know what to call them. I think it's a bit like saying, 'You shouldn’t feel guilt.' Well, if you've lived in a world where you’ve been complicit in oppressing others, guilt might be natural. There’s a lot of white guilt in South Africa, but other forms of guilt exist, too.

But shame is more interesting to me because it's such a primary, visceral experience, and it’s less about the ego. It’s more like a complete erosion of self.

It's about you and the world.

Yes… (Both look around, realizing they are the only people left). I suppose we should go now; they are closing the museum.

Right. Thank you!