Painting is an assessment of a time

An interview with artist Luc Tuymans

Luc Tuymans is one of the most prominent painters of our day, and it seems that the present pandemic has not really disturbed the intensity or pace of his work. He has participated in many prestigious group shows, and his paintings are currently on display until December 31 at the newly opened Bourse de Commerce – Pinault Collection in Paris. He has collaborated with Luc Steels (a leading AI expert and founder of the Artificial Intelligence Laboratory at VUB, or the Free University of Brussels) to analyse the relationship between contemporary art and AI using Tuymans’ paintings from his La Pelle exhibition at Venice’s Palazzo Grassi in 2019 as a point of departure, a project that resulted in the Secrets exhibition at Bozar in Brussels this past spring. And at the end of last year, Tuymans’ solo exhibition Good Luck opened at the David Zwirner gallery in Hong Kong.

His exhibition Seconds, dedicated to our pandemic-era world and the feelings it has brought out in people, just recently closed at the Zeno X Gallery in Antwerp. “With this exhibition, Luc Tuymans is seeking to create pertinent images in the midst of a global crisis,” read the exhibition description. In regard to the present time and his place in it, Tuymans commented during our conversation: “Doing the job that I do, which is painting, which is kind of a lonely enterprise, there has not been that much change for me on a professional level. The only thing that changed is that normally I would travel five months out of the year. In that sense, the pandemic was quite a stark reminder that we actually make a lot of unnecessary trips, a lot of unnecessary travel. So in that sense, this lockdown was not necessarily a negative thing. This year has not been negative for me. And that’s at all levels. In terms of attention, the show in Hong Kong, which I couldn’t attend, was a success. Things online also function, although I think it’s still preferable to see things physically and in real life, especially when we’re talking about painting. It’s an experience to look at it.”

Tuymans is currently working on his next exhibition, which will take place next June at the David Zwirner gallery in Paris. It’s about the polarisation of the world, and he says it’s already nearly three quarters finished.

This is a speculative question – will the pandemic change the art world and humanity in general?

I think there will be changes, necessary changes that are not completely linked to this experience of the pandemic. I think they’ll be more temporary, but what this pandemic has done is actually question the need for and of things, which is positive. Sort of like trying to strike a balance, trying to decide what’s really important, what one should prioritise and what not. Because, of course, the art world is becoming exceedingly corporate, and that’s not going to be completely destroyed by the pandemic. Not in the least. It will actually overemphasise that action. So therefore the necessity to create something in the middle in the art world – that is really important. It’s important that you not only have grassroots, but that you also have something in the middle. Because that’s your life source. That and how that’s organised might be inspired by what we’ve been through in this pandemic. When we get rid of looking at our own label and start looking a bit further than the self itself.

So, that will hopefully happen when this pandemic situation sort of normalises itself, which will take time. But it will eventually become part of our lives. That is, viruses and pandemics will become a recurring element in our society.

But I’m a bit more worried about the political fallout of this situation. And that, of course, can also have a cultural implication. In a sense, the political fallout of most pandemics has always been negative. There have been a rather great deal of missed chances in terms of the West having been unable to cope with a pandemic like this. For example, the European community missed its chance to really make a profile of itself as an at least organised entity, which it didn’t do.

So in this sense, all these elements have increased and become much more convoluted. And I think it will be kind of the same situation for the art world. At first, it will be a rather confused, convoluted situation to sort out, and then they’ll go back to what they know about. At least that’s what I think. But at the same time, I hope it will be informed by other things. I also hope it will be informed in an intelligent way.

Luc Tuymans. The Stage. 2020. Oil on canvas. 250,4 x 268,2 cm / Courtesy: Zeno X Gallery Antwerp

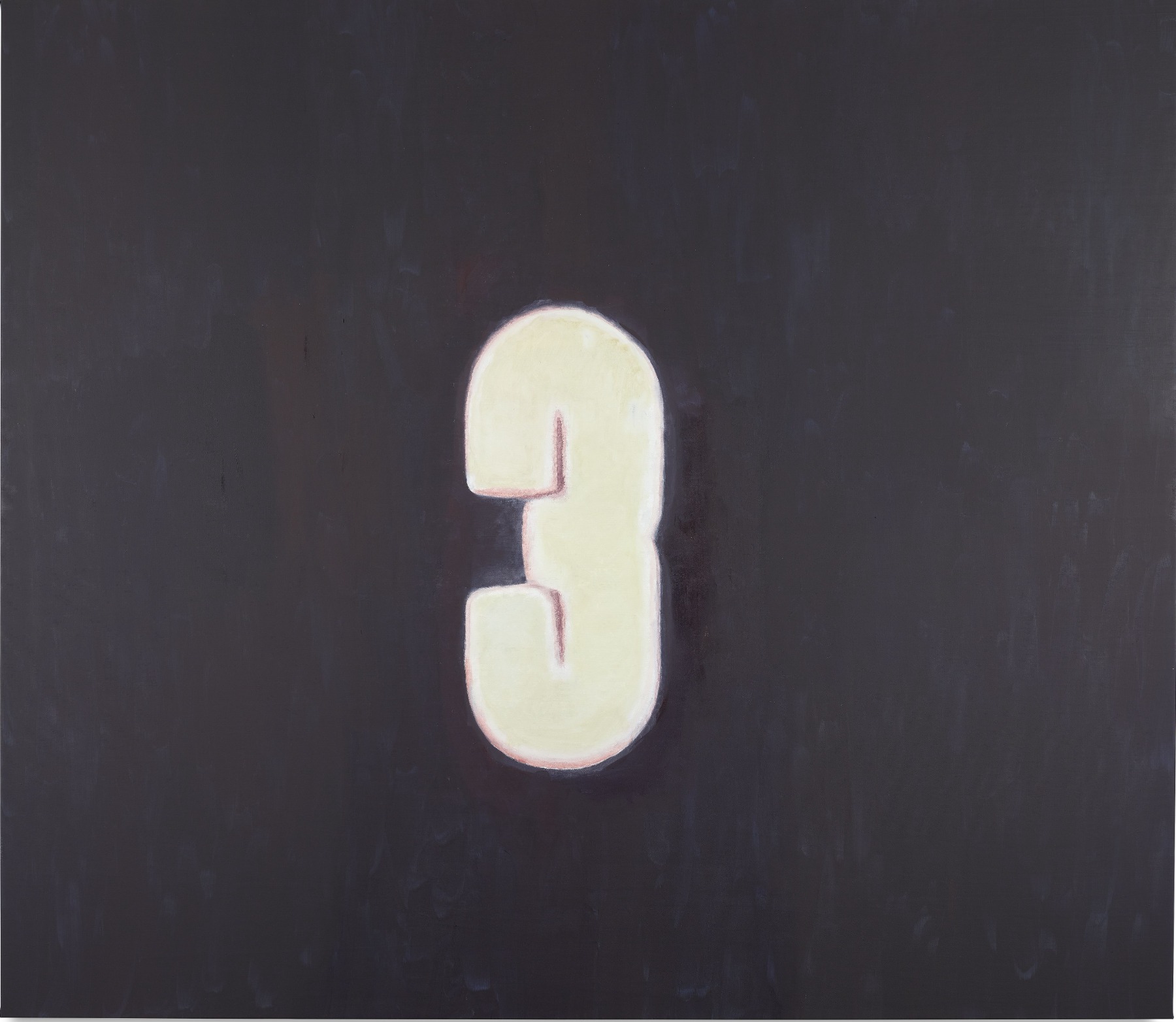

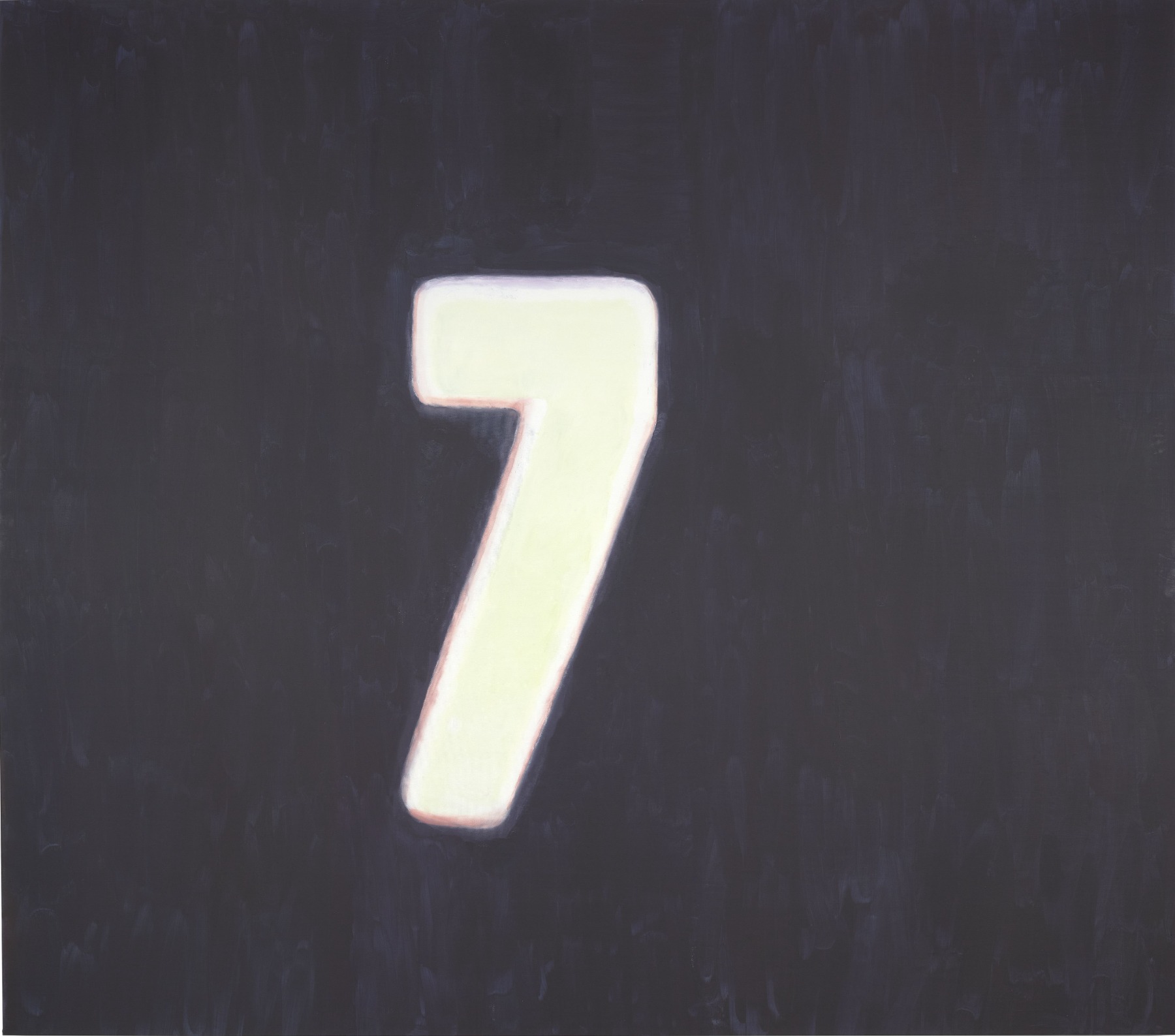

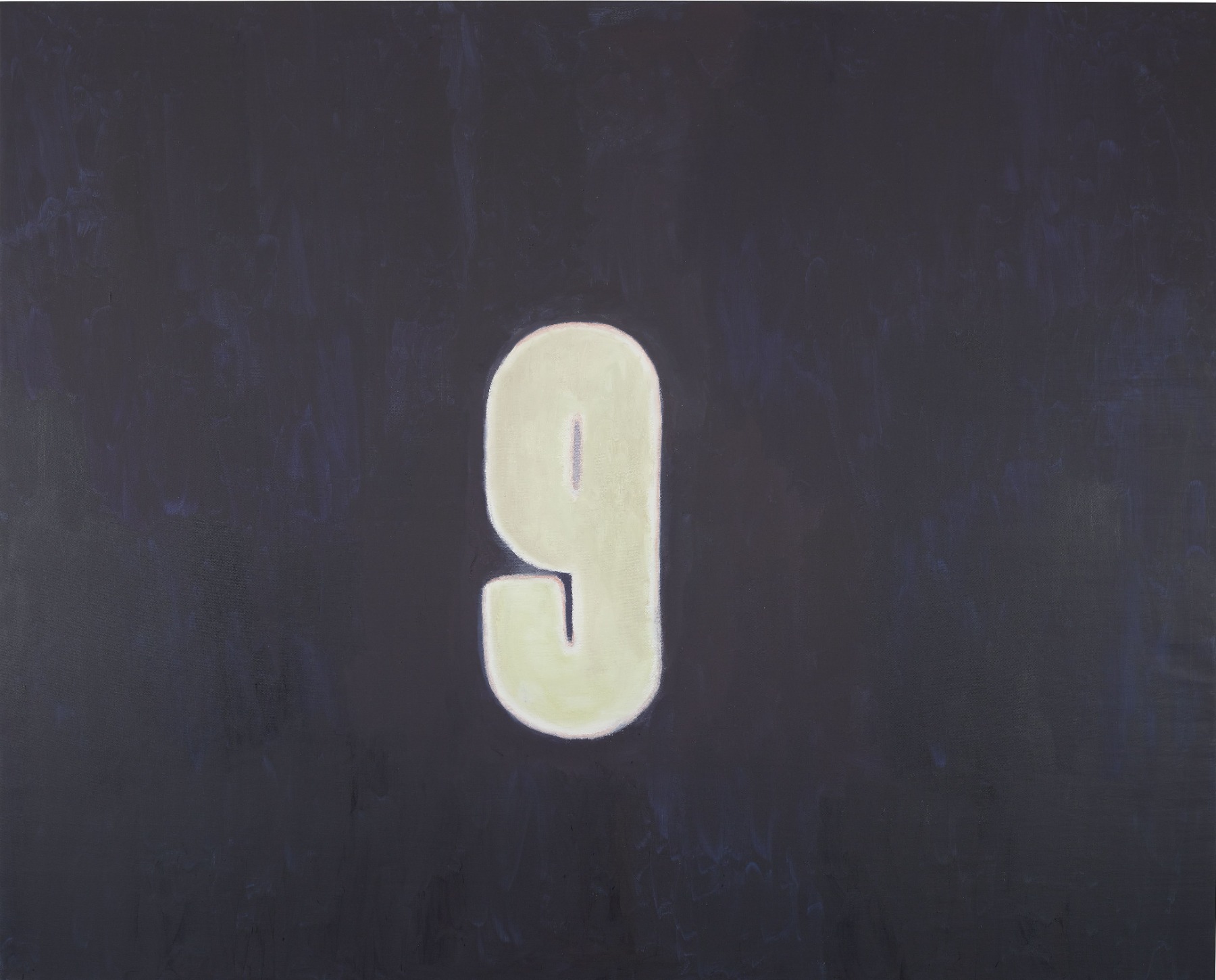

Your Seconds exhibition at the Zeno X Gallery, which closed just very recently, was dedicated to this time of the pandemic. At its centre – next to two figural paintings featuring the images of an empty stage and the sky, as well as an animated film – were four large-scale works depicting numbers set against a saturated dark, black background. Why did you choose numbers to represent your feelings of the pandemic?

It all started with Artforum magazine, whose chief editor asked me to make an image of the virus itself, whether a drawing or painting or whatever. Which I thought was… idiotic. And so I came up with this idea that, since it’s a pandemic, that means it’s a global thing. I mean, it affects everybody. So I felt I should come up with imagery that expresses that feeling – a nearly anonymous point of view, which on the one hand is abstract and on the other hand isn’t. And that’s how I arrived at these numbers, which go pretty far back in time, because when I painted my paintings in the 1970s, I used to use a calendar, from which I tore off the dates, but always from one to ten. I would cut them out, paint them black, and then I would glue them on the surface with the paint of the painting. Most of those paintings are now destroyed. But on some of them you can still see the mark of one of those numbers. And later on, I also used them as a subdivision. I filmed them then, with Super 8s – white on a black backdrop, and that’s where these numbers actually come from.

Luc Tuymans. Numbers (One). 2020. Oil on canvas, quadriptych. 277,2 x 310 cm / Courtesy: Zeno X Gallery Antwerp

So it was an idea I had had for a long time. But this time I thought it was really relevant, because we subtract and we add numbers all the time. There’s this sort of… this sort of constant occupation with numbers. And as I said, this subtracting and adding of insurmountable things, whether it’s life or something else. So in that sense, I thought it was an interesting idea. And so I made them for this magazine – on paper. I used SketchUp to enlarge them in a sort of like ideal space to see what it would produce, and eventually I decided to paint it.

Also, the black background in these paintings was quite important. But it’s not really black; it’s actually a combination of indigo and violet. If you get up close (and this is something you don’t see online, because it’s not as graphic) and you’re in the same space, you see that the numbers, of course, have colours. They’re also the size of a child or two. It becomes very personal in a sense. And the way that people have reacted to them is kind of personal, too – they either like it or they just completely hate it. I mean, there’s something disheartening in those numbers; they also create an atmosphere, they create a total environment. These four numbers, they become more singular. I mean, they take on a life of their own, in a sense.

I also want to add that this is a reference of sorts to the experience I had when I went to see the Rothko Chapel, because there, of course, the paintings become the environment. And also in the sense that there’s a little reminiscence of that point, too. But most of all, it’s that these paintings become like sculptures. And that was actually an aim.

Luc Tuymans. Numbers (Three). 2020. Oil on canvas, quadriptych. 280,2 x 325 cm / Courtesy: Zeno X Gallery Antwerp

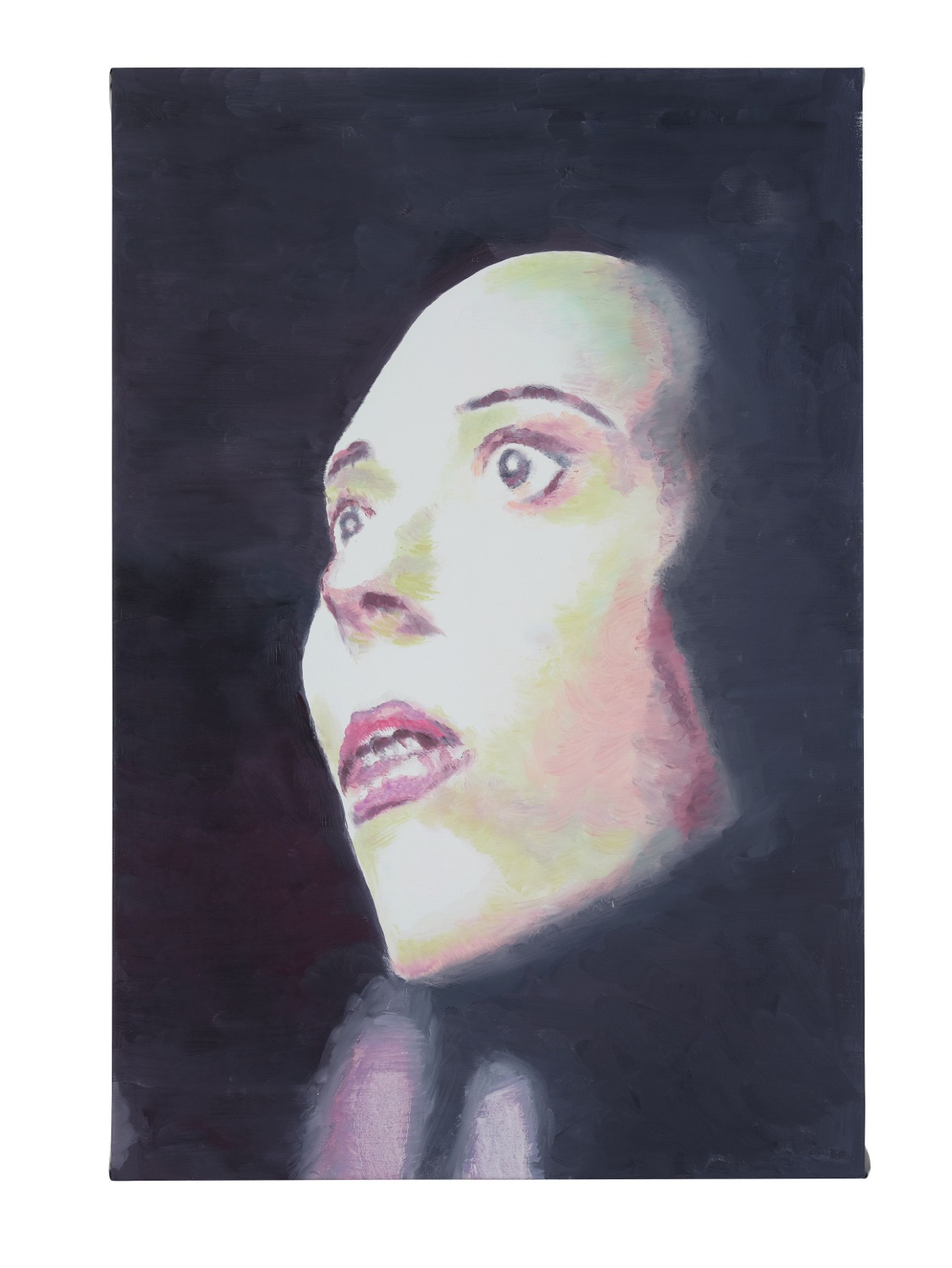

Speaking of feelings over the past year and a half, I think your painting Twenty Seventeen, which you made in 2017 and is about everything that was happening at that time – Brexit, Trump, etc. – might precisely capture the emotional backdrop of the present moment.

Yes, of course. At the moment, this painting, which was the poster child of my show at the Palazzo Grassi in Venice, is on view at the group show at the Bourse de Commerce – Pinault Collection. The interesting thing about this image is that it’s not a real image. It’s a generated image, which leads to the question of what’s fake, what’s real and all those things. On the other hand, it’s also an exaggerated image. It’s an image of today; you can see the element of fear portrayed in the eyes. It’s a very baroque image. I don’t paint a lot of baroque images, but that one could be as close as I get in that sense. And so, yeah, sure. Paintings are interchangeable; they never have just one meaning, they always have ambiguous meanings.

Luc Tuymans. Twenty Seventeen. 2017. Oil on canvas. 94,7 x 62,7 cm / Photo: Studio Luc Tuymans / Courtesy: Pinault Collection

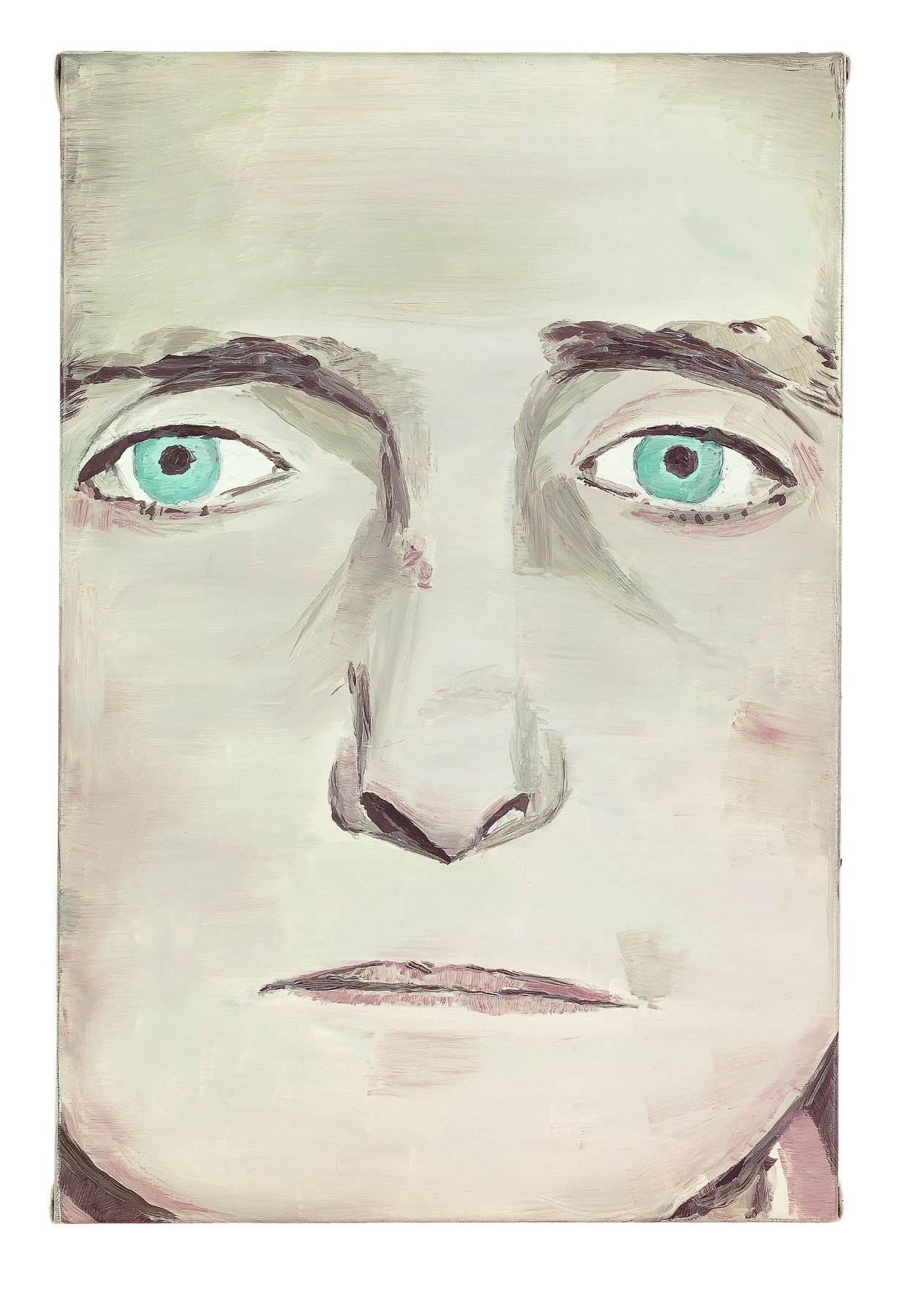

You mentioned the eyes in the image. That’s a very important element, and not only regarding Twenty Seventeen.

People always say that the eyes are the mirror of the soul (laughs). That’s one thing. But for me, the eyes are also like blanks. Actually, it took me a long time in my oeuvre before I began paying attention to that. I didn’t paint portraits; I painted toys and things like that. When I finally came to the portrait, I didn’t want to paint portraits of psychology. I wanted to paint portraits as something that would be like missing the reality, like nearly symptomatic in a sort of like… I don’t want to say in a scientific way, but in a way that you just look at it. I mean, as an object, basically.

Luc Tuymans. Der diagnostische Blick IV . 1992. Oil on canvas. 57 x 38, 2 cm / Courtesy: private collection, on long-term loan to De Pont museum, Tilburg

The eyes in a face are the primordial point where you make a connection with the physiognomy and with what could be – still on a psychological level – there or not there. But again, it has to be ambiguous. The woman in the painting Der diagnostische Blick IV (1992) was depicted as looking into the camera. So, she looks out of the image, but in my image she looks over you. I mean, you don’t have this connection with her. And that’s what I’m fascinated by with the eyes, because they’re like glass. On the one hand, there’s something very fragile about them; on the other hand, there’s something extremely cold, something extremely objective.

But with this particular portrait in Twenty Seventeen, it goes in a different direction. But it’s possible, because it’s a projection of a face on a doll. So, not a real face. And this was what really fascinated me. And also, in the context of what was going on at that time with all the extreme polarisation, the confusion and so on. All those elements sort of like made that image relevant for me, and that’s why I called it Twenty Seventeen.

Political references, history, historical events and processes – these have always been part of your oeuvre. Also the Second World War, Europe’s colonial past, current political events. Why is that? Does it have to do with your own family’s story, which might in some way trigger conversations about these things, and then you maybe try to “paint them off” of you in some way? Or is it a way for you to understand the world in psychologically challenging, problematic and frightening situations?

Of course, there is the autobiographical point. I’ve talked quite openly about my family, one side of which is Flemish and collaborated with the Nazis. And also about Flemishism, which still is in imminent danger in the country in terms of separatism. The other side of my family was Dutch and was active in the resistance. I’ve talked about my parents’ unhappy marriage and about our family dinners. I mean, every time at dinner time, these things came up as a sort of recurring element. But they’re also important in the big picture, because after the Second World War there were no more European empires. You only had nation states and the European community, which I think is still the only solution to the problem.

And I also didn’t want to make art just for art’s sake. I mean, it’s not like I don’t see art as inspiring. It is. And there are artists and art that inspires me. But it’s much more the people that I admire. I cannot really develop something that… I can only develop something out of reality, which is something that’s very connected with the region where I come from. If you think about Belgium, first of all, it’s a very young country; it was only founded in 1830. I mean, the region is, of course, much older and has been overrun by foreign powers very many times. So there was this sort of opportunism, which was necessary in order to survive. The element of survival was important, even as a visual. We didn’t have time to be romantic like the Germans or supranational like the French. Here, there was always this connection to the real world. It goes from Van Eyck to Ensor – it’s all based on real themes.

Luc Tuymans. Intermission, 2020. Oil on canvas. 254,1 x 243,6 cm / Courtesy: Zeno X Gallery Antwerp

For me, the Second World War is interesting in a larger context because of all that came out of it. Of course, we are certainly still now living and experiencing the consequences of what happened back then. For example, the extreme polarisation of the United States, the extreme polarisation of the world, you see all these elements coming together. You also see it in what Trump referred to and I suppose we haven’t seen the last of it yet.

And also the idea of what democracy is, or what democracy still is, or what it still could be perceived as, which is important, especially for the region we’re in, which is Europe. So in that sense, all these things still come together in a sort of constant information flow. I find all of that extremely interesting. I need to base my oeuvre on a building block of an element of history that’s kind of close in a sense. And of course, now that history is slowly evaporating. It will eventually become a fetish at a certain level, which I think is interesting, too. People forget that’s an idea of the oblivion that’s important. But at least it’s based on my interest in history, and also the idea of consequence. I mean, the idea of something that has an massive impact on the real and also on the visual.

Today we’ve become obsessed with political correctness. Don’t you think we should leave art as a field where we’re not obligated to act in certain way, to create according to what’s right and what’s wrong? Do you think it was right, for example, to postpone the Philip Guston retrospective, which seems to be the loudest recent expression of misunderstood political correctness?

I don’t understand the controversy regarding Philip Guston. I guess his art is relevant today, but

I understand the fact that there’s a problem in the sense that, of course, it’s important to reevaluate. I mean, bodies in the museum, what is being shown, and of course, we’ve much delayed doing that, but that has nothing to do with what Guston actually painted or said or meant. So there’s a big confusion here. And the same goes for genders, the idea of race and all those things. I don’t care if the artist is male or female or trans or whatever; if the art is important and interesting, then it’s valid. That’s a different form of validating things from a certain perspective, which is a perspective of empowerment, which is always a very difficult situation. I mean, the idea of power itself is a very complicated matter.

I’m interested in power and depicting it and also in the power of images, but not for the power itself. I mean, it’s actually much more to be intrigued with the mechanisms of power and trying to depict it so that it also creates a certain understanding and, of course, opens a form of dialogue and doesn’t shut it off. The dividing of society is highly destructive for culture because you get two opposite sides that make a pincer movement in which they actually collapse culture, which is not really something you should do.

Art is sort of a free zone, and creativity is important. But it’s also something that could be partially immoral. But why not? It’s not bound to those elementary understandings of what should be allowed or what should not be allowed. But that’s now creeping into our society for sure. That means you have to be even more subtle.

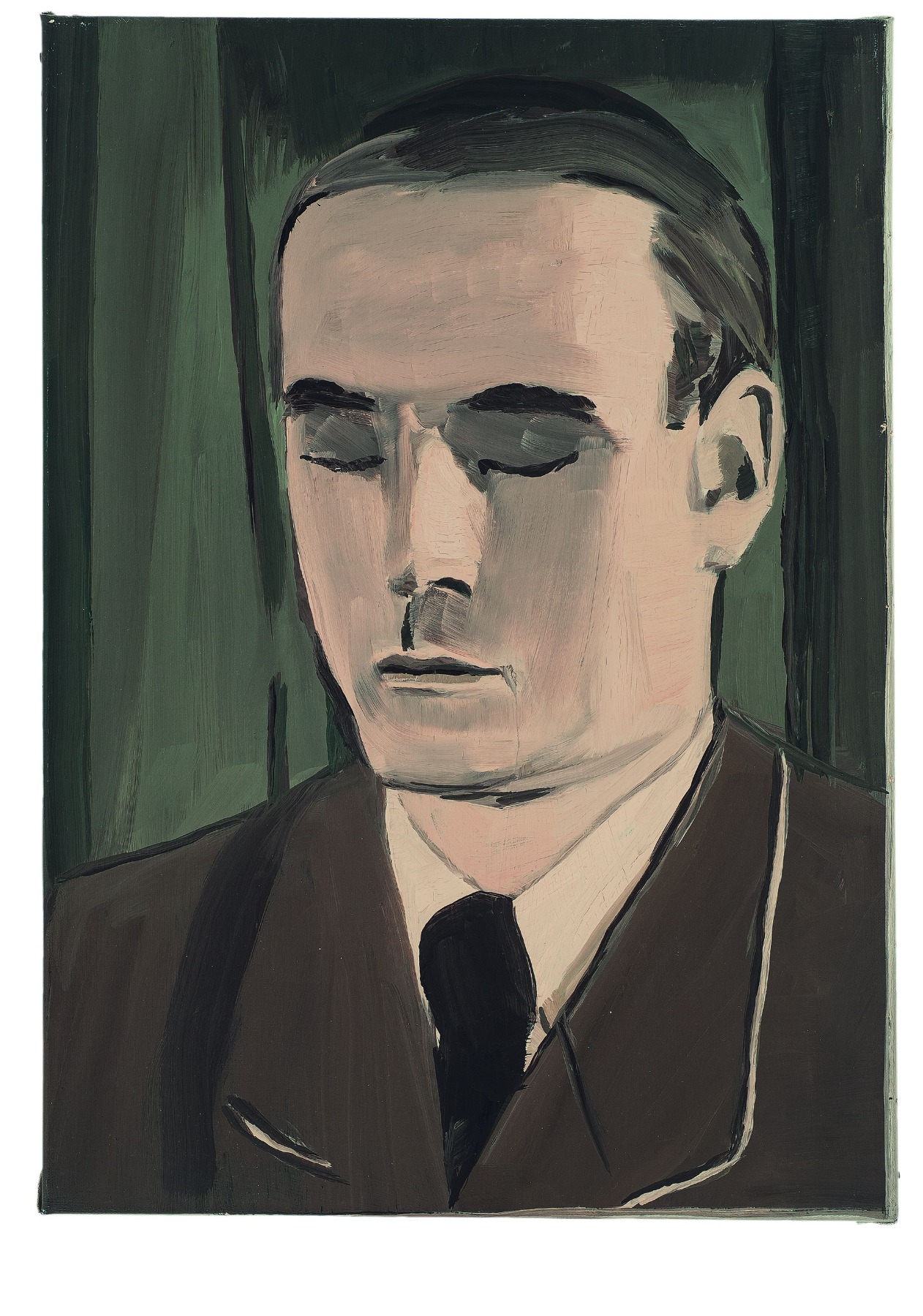

Luc Tuymans. Secrets. 1990. Oil on canvas. 52 x 37 cm / Courtesy: private collection

You once said that we can’t clean up the history of Europe that has already passed. Can we free ourselves of our past simply by taking down monuments and hiding paintings?

We should instead contextualise monuments. That would be fine. It’s probably necessary.

It’s an educational point. I mean, one should not forget history. But history, of course, can be adapted to the point where it becomes contextualised and it can actually be enriching instead of destructive. It should not be seen as a danger. History is a part of the reality that has been, even if that reality was a misunderstanding or a great mistake in terms of humanity. The Holocaust is a perfect example of that, in the sense that there’s a need to contextualise it. That I do agree with. To completely abolish it, of course, would lead to many more problems, because you’ll not be able to enter into dialogue anymore. So, if you want to make the elements diverse, you make them a bit more complicated, but at the same time they become more interesting. Otherwise, they become just blanks; they become either this or that. And that, again, is polarisation, which is a tool in the hands of powerful people. And it actually makes people stupid. That’s basically what it does on a personal level.

Of course, polarisation can also empower elements along its way to abuse it even further. This is what I actually foresee. This is the game that’s being played. And that, of course, narrows down the individual as a person who can think, but I think it’s important that that at least should remain a possibility.

This all creates the conceptual background, the narrative of your art, but how important for you is the substance of a painting, the formal tools? Does a balance exist between those two things? Which of them is more important? I remember seeing your work in the Belgian pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2001. At first, I was surprised and excited precisely by the materiality of your paintings; only later did my attention turn to one of the significant narratives in your art, namely, the Belgian Congo.

Well, both aspects of painting are important to me. Back then, we did the Belgian Congo theme because the Belgian pavilion, where this series was exhibited, had been built by a colonial architect. It was political because the biennial is a political thing. It was different than the other paintings that I’ve made.

Whenever I know what I’m going to paint, I also try to figure out how I’m going to paint it. Those two things should be intertwined with each other in the sense that they’re not foreign bodies. They should sort of work together. On the other hand, it’s not necessary for everybody to know what I’m trying to mean with these paintings or what I’m trying to get across as a message. That’s up to the viewer. The viewers might see something completely different, which is fine, too. For me, it’s important that what I paint is objectively presented imagery and that at least I know what it is and why I feel the way I feel. It’s not that I can paint everything there is to be significant to what I choose to depict.

Another important thing in your work is domestic scenes and normal, everyday life, if I may describe it that way.

But even if I paint domestic scenes, many still regard them as political, which I think is also stupid. Ever since I did the Belgian pavilion in Venice, I’ve been propelled as a political artist, which I don’t agree with. I mean, I don’t think any artist… Well, maybe an artist is political and can have a political stance at a certain moment in time, but you cannot load up artwork in a political sense from the very beginning, because then you’re just making propaganda. But that’s not what’s interesting here.

What’s interesting is the anachronism of painting itself within that space of… I mean, life is political. Everything, every human transaction is political. And in that sense, I think it’s important to keep that element of a free space and the freedom where you do not need to conform to any form of moral judgment, you just perceive things. I think this idea of perseverance within this idea of perceiving things is interesting for the visual, because it brings different signifiers and a different apprehension of what you could know or not know. And also, when I try to paint the painting, I have this problem that I have to be intrigued by it. Or else I need to not understand it; I don’t understand why it’s important or not, and then I have to make it in order to fully explain it. In other words, I have to turn it into a visual, which is also a little bit compulsive, but I have to do that.

All the domestic elements could actually easily turn into something horrible in a sense. It’s always this sort of very ambiguous zone and also more of a tendency to look at things that are a little bit out of sync. Things that don’t really fit, although they could fit, but they don’t. There’s this element of collage in the image, in which the image becomes interesting to me because it’s sort of like superimposed on itself. And then it becomes painterly possible to do something with it.

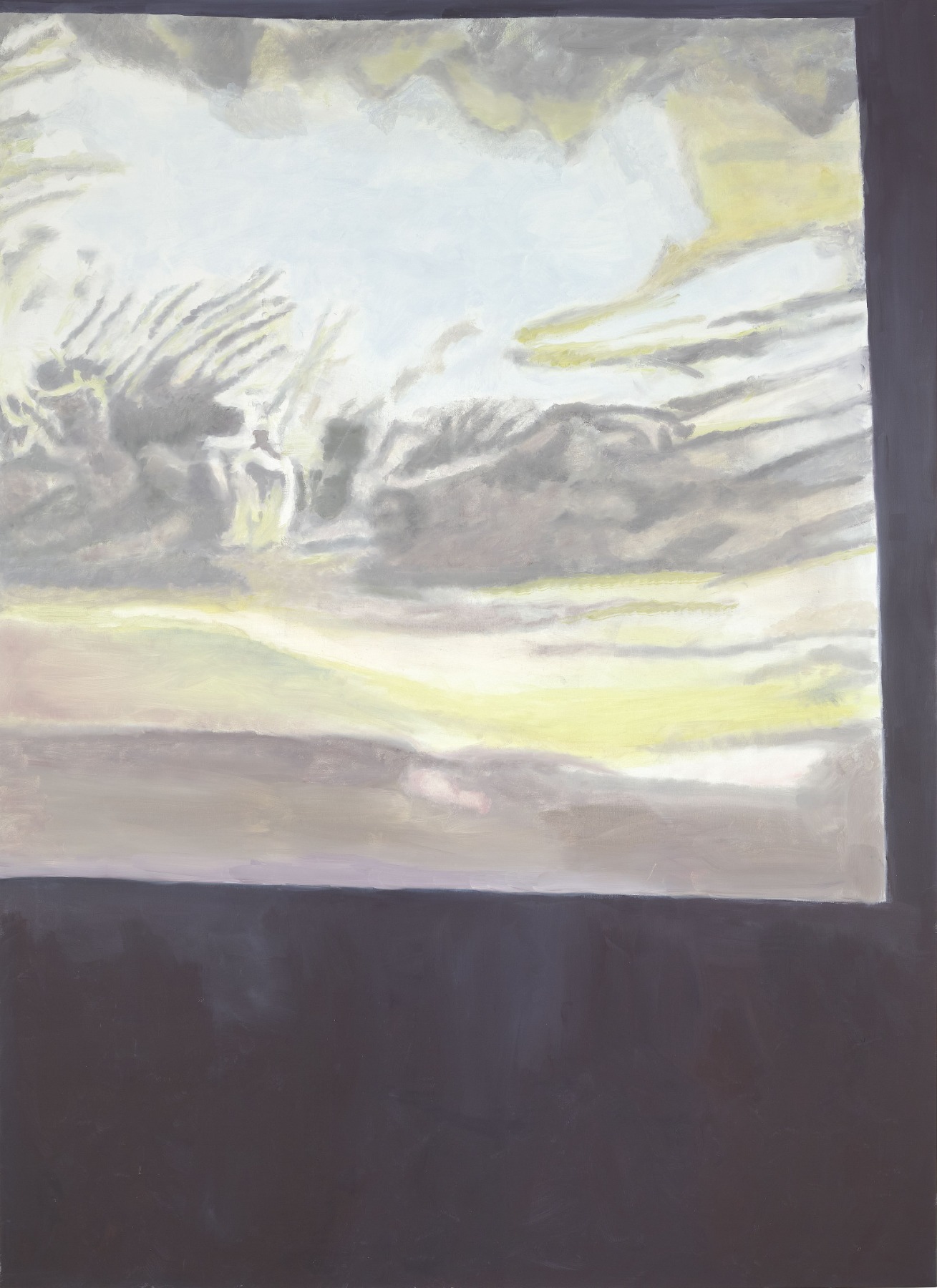

Luc Tuymans. Clouds. 2020. Oil on canvas. 279,5 x 203,6 cm / Courtesy: Zeno X Gallery Antwerp

Non-colour, transparency, a kind of fragility – these are tools you use very often. How did you arrive at them? Is it connected with your break from painting in the 1980s, when you focused on filming with a 16mm camera? Because there’s the same feeling of substance, the same feeling of softness.

My paintings are about tonality, which is, again, something that’s very regional to where I live. Most of the time the sky here is grey, but it’s also very translucent in a sense. And then, it’s not just that the perspective is the illusion of space on the two-dimensional plane. There’s something else, and that’s tonality. The tonality is important, because tonality has a temperature – it’s warm or it’s cold or it’s in the middle. It’s a mixture of several colours instead of a single harsh colour. Like, if you look at Ellsworth Kelly, you see a sort of more sculptural adaptation of painting. But if you look at Van Eyck or many other painters from this region, you see tonality, which means there’s this element of real depth within painting, which is something different.

So, if you look at my work, there’s a lot of colour. And it’s also important that when people see a painting, they should remember it. They should not remember it as a photograph. It’s actually much more complicated than that, and the algorithms are turning out to be having a great deal of problems with painting because it’s too complex. A photograph is easier. It’s because they’ve learned to do that and have not learned to look at painting as most viewers already do. So therefore, they perceive it in one way or the other. And some people perceive it as monochromatic and others don’t. But the more you look at paintings the more intensely you actually examine them, and you see that that’s not the case. And then they start to work on your memory. That’s the reason why.

But coming back to your movie period…

Film is really important to me. I had stopped painting because it became too existential, too suffocating, and I was actually too close to the image; I didn’t have the distance. And then by chance I began filming with a Super 8 camera, and eventually with a Super 16. But then I came back to painting because it was a five-year project and not much had really come out of it, except that what the lens gave me is the right distance to look at an image. For example, a close-up doesn’t really exist; but it does exist in film. This means that you make an edit of your idea; you crop it, you can manipulate it, you can realise your dream. These are opportunities that are provided not so much by photography but by the moving image. I’m a child of the television generation. The transmitted image is very important. But it’s important to pause it, to freeze it, to take motion and make it motionless.

That goes to say that I also have a preference for my imagery to not really remind you of sound or music; it gives you a sense of this elementary silence, which I find important and is, again, linked to this freezing or pausing of the imagery.

So, yes, of course, this has a gigantic influence. Also because filming is quite close to painting. I mean, I would be a very bad photographer because I would always be too late. Photography’s in the moment; you know, you just take the image. With film, you actually approach the imagery, you can even edit it while you’re filming (in the lens). But with painting you also have this approach – you can overpaint it. So you can see that there’s this huge similarity between filming and making a painting.

But you paint very quickly.

You know, I merely execute paintings. The time before I start to paint is the most worrisome. The biggest part of painting is actually the whole process of arriving at, of choosing the imagery, of figuring it out, and that takes months. This includes the research that I do, and lots of drawings, watercolours, even working on the computer, to try to figure out the imagery. Once that’s done and the imagery has been analysed to death, so to speak, then I go to paint and I don’t want to think about it anymore. I don’t want to be thinking on the canvas. Not that. That doesn’t happen. But there are some things that do happen, things that I cannot foresee, and there are still things that I don’t see completely. But I don’t want to try to figure out something while I’m painting. No, at that point it’s all about my brain going into my hands, so that I intentionally get it right. It happens organically somehow. It’s not like I pragmatically decide to make a painting in a day.

That all just developed as a sort of a ritual or something like that. But it means that I have to have this sort of extreme moment of timing and precision. A moment in which I actually do this. Like somebody who’s doing an operation, like a surgeon who takes a piece of a body and only looks at that piece and not at the rest of the body. I tend not to work on several paintings at the same time. I just make one painting, and once that’s done, then comes the next painting.

Luc Tuymans. Numbers (Seven). 2020. Oil on canvas, quadriptych. 280,4 x 319,7 cm / Courtesy: Zeno X Gallery Antwerp

You’ve always been very deeply connected to cultural heritage, art history, literature. You’ve many times emphasised the importance of Jan van Eyck’s role in the history of Western painting. El Greco’s paintings have played a role in your creativity. At the beginning of our conversation you spoke about the Rothko Chapel. Would it be true to say that your painting has in some way emerged from all of these layers of the past and that the final layer is the present, the time in which you yourself live, and that in some way your paintings are separate from you once they’re finished?

Yeah. I mean, that’s what it should be. Painting should be multilayered. Painting is also a different assessment of time. This is where the numbers are actually quite interesting, because they also deal with time in a sense, or they could potentially do so. This is what’s fascinating with painting, that it creates its own time. It’s not real time; it’s painted time. And of course, in terms of being multilayered, it has to be that.

Although it’s physically made by somebody – in this case, me – once a painting becomes an object, it becomes something detached from myself. I don’t paint on a frame; I just paint on a canvas nailed on the wall. But whenever three or four paintings are finished, we put them on frames and they change. They get a sort of second skin, and I can then look at them in a different way. When you look at them when they’re still unframed (which means not completely finished), they actually show more; they’re more accessible, which is kind of weird.

I think this element of attachment is important in order to create this multilayered aspect within the visual, because otherwise it’s not possible.

Luc Tuymans. Numbers (Nine). 2020. Oil on canvas, quadriptych. 277,4 x

343,3 cm / Courtesy: Zeno X Gallery Antwerp

Over this past year, much has been said about art as a tool of healing and about art’s ability to influence processes. At the same time, these sentiments are just pathos if people aren’t able to find the essence of art, if they don’t know how to look at art. How can one discover the nature of art?

It differs from person to person. You cannot make art for everybody, otherwise you’d be making something which, again, would be propaganda; or else you’d be instrumentalising art, which is something one should never do. One should also never be overly didactic when it comes to art. The best way to look at art is as a kind of a primordial, experiential sensation.

Of course, I’m a contemporary artist, and so the understanding of the audience is already incorporated, because we’ve become democratic in our convictions. We’ve already changed; there’s this understanding of what can be perceived. The idea in my work, which is really important, is the distance that you measure between the viewer and the work itself. That measurable distance is part of the signifier of what you’re looking at, and you can see that from a distance they function. Once you go closer, they sort of disappear. I mean, they just disintegrate. That’s a very fascinating element.

And that’s an experience that everybody can have. There’s no learning process needed for that. It’s a sort of elementary experience that you can look at something and be like… just like a kid who looks at things. That’s the most honest thing you can have. A child looking at your work and seeing what she or he thinks of it – that’s the most rewarding thing. Because there’s this element of innocence. It’s very important to not overestimate an audience or a viewer, but it’s especially important to not underestimate them. That’s the most important thing.

Luc Tuymans. Photo: © Alex Salinas