What were the Estonian noughties like?

A conversation with curators of the exhibition ‘Art in the Comfort Zone? The 2000s in Estonian Art’ Eha Komissarov and Triin Tulgiste

The Tallinn KUMU art museum is continuing its series of exhibitions introducing to the most recent history of Estonian art. At the time of the inauguration of the museum in 2006, the permanent exhibition of KUMU ended with the Soviet era; today, it is continued by ‘The Future is in One Hour: Estonian Art in the 1990s’, a section of the permanent exhibition opened almost two years ago (curator Eha Komissarov). It was preceded by ‘The X-Files [Registry of the Nineties]’ project (curators Eha Komissarov and Anders Härm) that made quite a noise in the spacious galleries of the KUMU museum back in 2018, but November 2021 saw ‘Art in the Comfort Zone? The 2000s in Estonian Art’, an exhibition mounted by curators Eha Komissarov and Triin Tulgiste go on view at the same venue; it is open through 9 October 2022. On the one hand, the current show seems to be engaged in a dialogue with the future: after all, the featured artwork laid the foundation for numerous Estonian contemporary art trends. On the other hand, it also evokes nostalgia: the author of these lines remembers quite a lot of the exhibits in the context of their ‘premiere’ at the time when they did not quite belong to the history of art yet, being an integral part of the live art process.

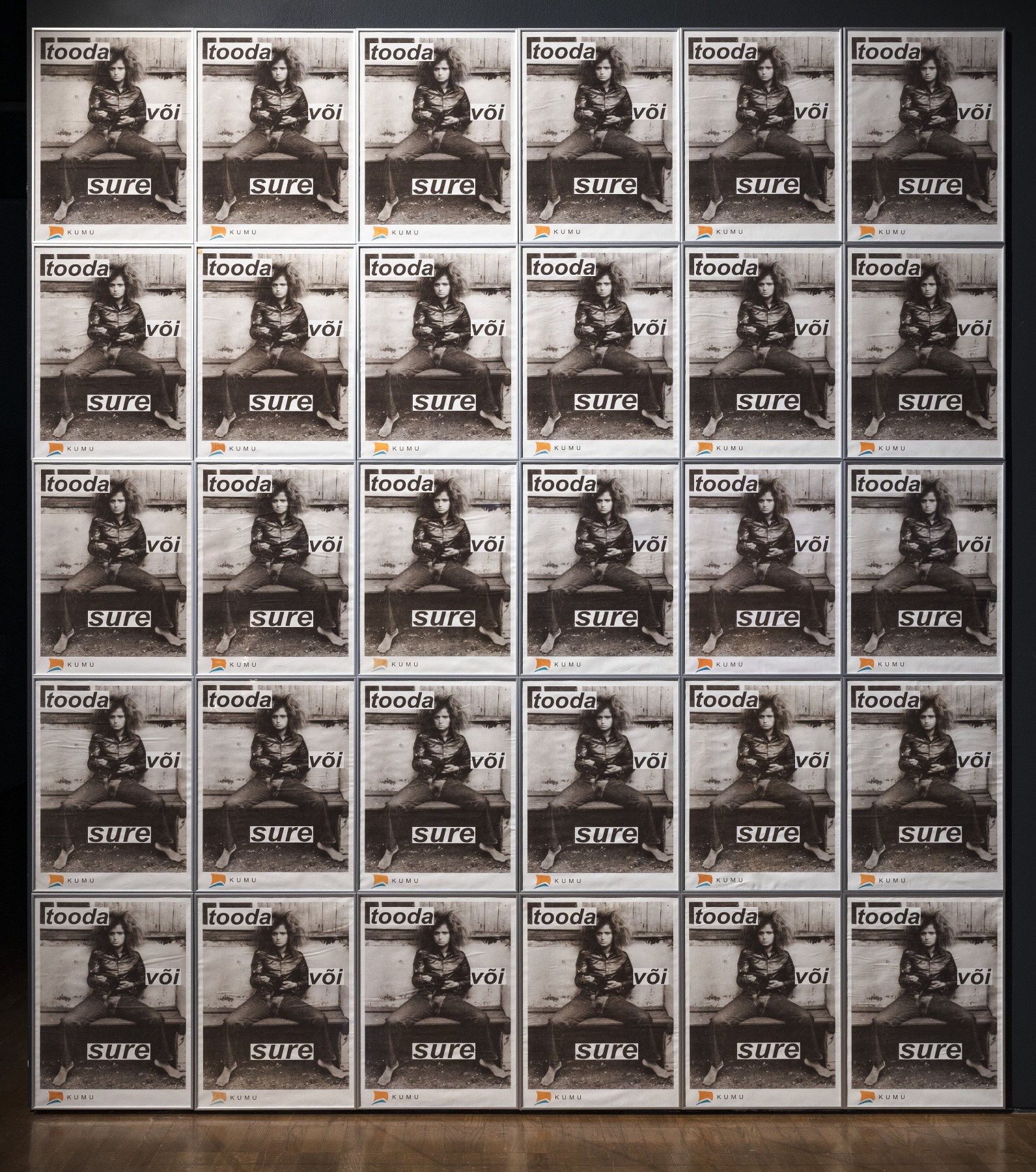

Marge Monko. Tableaux II. From series 'Studies of Bourgeoisie'. 2006

Could you tell us about the idea of your exhibition ‒ how was it born? When we are dealing with parts of the most recent art history, there is always the question of whether enough time has passed for them to be viewed in a detached way. Have we gone far enough from the 2000s to speak about them from a historical perspective? Or perhaps the project was guided by a need to review the latest additions to the contemporary art collection of the Art Museum of Estonia (EKM)? What is the proportion of exhibits from the EKM holdings in the exhibition?

Eha Komissarov: Considering that for several decades now ‒ since the restoration of the Estonian independence ‒ new works are added to the EKM holdings every quarter, funded by the State Capital Foundation of Estonia, the need to review and re-evaluate our collections seems to arise quite naturally. The new additions go on to be featured in various very different exhibitions and ambitious curatorial projects, of course, and yet the museum as the owner of the collection does need to form its own objective view of the actual situation. A certain question emerged among the Estonian art critics: why choose the noughties? It is such a boring format to use for defining the problem. However, in a situation where the development of contemporary art has become so entropic, where the categories of artist or art medium have become practically invalid, because everything is constantly crossing all sorts of boundaries ‒ in this situation the notion of a decade introduces at least some semblance of objectivity, and this is exactly what the museum needs. And it is a global trend: if a certain general picture is what is called for, you should build an overview of contemporary art decade by decade.

Triin Tulgiste: I believe that in the case of the 2000s the distance required for an initial summary is already there; this has been confirmed by the interest of other museums in the dynamics of this decade (see the ‘Naught Mood. Estonian Fashion Avant-Garde 2000–2010 at the Estonian Museum of Applied Art and Design, to name but one example). As for re-evaluation of the museum’s collection ‒ in the case of this particular show, the impact of the museum’s exhibition programme on its acquisition and collection policy has become very obvious: it was thanks to this exhibition that we added a number of works dating from the noughties to our holdings: pieces like ‘Produce or Die’ (2007) by the Elfriede Jelinek School of English Language art group and ‘Guestbook of a Heart’ (2005/2021) by Sandra Jõgeva. As for the proportion, exhibits from the EKM holdings constitute one third of the works featured at the exhibition; another third is loans from the Tartu Art Museum and the rest ‒ loans from private collections and the authors. And so the exhibition is, indeed, a review of additions to the museum holdings but at the same time also a question of what else could have been included in this overview of a decade.

The Elfriede Jelinek School of English Language art group. Produce or Die. 2007

E.K.: By setting itself such a huge task, the institution also takes on a big risk because it immediately becomes an object of criticism. The title of the exhibition was criticised quite a lot, among other things. But the thing is ‒ the 2000s are a subject that really does not lend itself well to branding. We can come up with just a couple of significant keywords, like the so-called Bronze Soldier and Bronze Night ‒ the mass unrest in Tallinn in 2007 as a response by the Russophone population to the relocation of a Soviet-era military monument. Also, the economic crisis of the second half of the 2000s. And that’s about it. This is why the museum felt it had to stage this conceptual intervention from today’s perspective. The title of the exhibition was born last year when the museum was summing up the consequences of the situation caused by the pandemic: we had been forced to cancel a number of exhibitions; the visitor numbers had significantly decreased, resulting in diminished profits for the museum. In this context, the 2000s seemed like a very calm and safe time; some new interesting concepts like ‘comfort zone’ etc. were articulated during this time. And that is why we decided to use the phrase ‘art in the comfort zone’ to describe this era.

Which predictably gave rise to a lot of friction, because, obviously, not everybody agrees with this kind of description. One of the problems, for instance, was the fact that is was in the 2000s that an autonomous circle of ‘self-employed persons’ emerged, devoting themselves to fighting for the rights of the artist. They are very active socially, which is nevertheless almost impossible to show in an exhibition. It is genuinely a somewhat anonymous activity but I do agree that it was a very important phenomenon in the context of the 2000s. Triin and I tried to reflect the work of the activists as much as possible.

T.T.: One of the defining factors for the show was the fact that as curators we were working in a certain grey area, so to speak – between two formats: the show is on view almost for a whole year, which is not the usual run of temporary exhibitions; at the same time, it is also not a full-blown permanent exhibition. On the one hand, we had to focus on reasonably stable works that could withstand the hazards of being on show for such a long time. On the other hand, based on our objective of introducing the public to the EKM collections and reviewing them, we tried to maintain a certain balance in the selection of the works: if we had focused, for instance, on the documentation of various happenings and performances, there would not have been enough space for many other materials. The size of the selected works was limited by the need to create the summary of a whole decade. It is a noteworthy fact that, for the first time in the history of KUMU, a continuous display narrative has emerged, offering an overview of the history of Estonian art from the early 1700s to practically the present day.

My personal associations and memories of the 2000s strongly resonate with the title of your exhibition. The 1990s were stormy and uncomfortable; it was still all about getting in touch with the methods of contemporary Western art and the new situation in the aftermath of the restoration of Estonian independence. Whereas in the 2000s, contemporary art was something taken for granted; it was present on a very high level; there was no need to prove anything to anyone. A situation of normalisation.

E.K.: These key words were very well flagged in a Finnish project under the title ‘Fly, Fly, Fly!’. If you did not live on the Berlin-London trajectory, you simply did not exist as an artist. You were not part of the global art process. It was mandatory to constantly follow the major exhibitions abroad and assimilate the current contemporary art experience. But now the lockdown has quite abruptly brought us back to the ground: this freedom of travel was, of course, a huge convenience, a privilege. If there was something in the era that people really feel nostalgic about then it is this physical freedom.

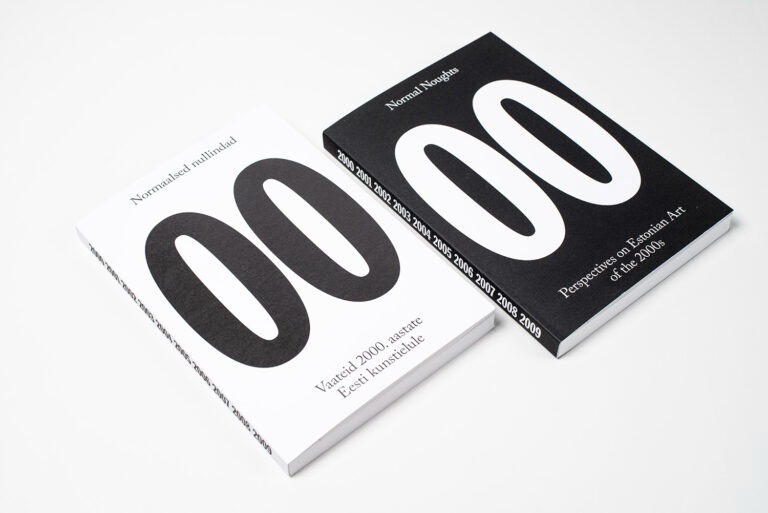

Publication ‘Normal Noughts. Perspectives on Estonian Art of the 2000s’. (Ed. Rael Artel. Tallinn: Estonian Centre for Contemporary Art, 2019)

What are the main thematic sections of the exhibition? My impression is that it is an exhibition centred around the works per se ‒ a kind of polyphony where you can also hear the individual voice of each piece. I found that the emphasis was on separate small and elegant dialogues between the individual pieces and that there was no attempt to subordinate the works to a single more general subject matter.

E.K.: Personally, I was very interested in the discourses initiated by each individual works. In simply giving the works an opportunity to speak for themselves without burdening them with artificially created labels.

T.T.: One of the partners in this dialogue at the exhibition is the publication ‘Normal Noughts. Perspectives on Estonian Art of the 2000s’ (Tallinn: Estonian Centre for Contemporary Art, 2019), which is first of all a sociological study of art. Since the publication presents a summary of the decade focusing on the art life in general, not on specific works of art, we thought it would be nice to make it a whole package by supplementing the book with a compilation of works created at the time. I am sure that the publication will find new readers now and the exhibition will serve as a database of images that should be kept in mind while reading the book.

As we mounted the show, it was important for us to create a dialogue both between the individual works and between the 1990s generation who were largely responsible for shaping the general image of the decade and the young artists who emerged on the scene in the 2000s. When systemising the material, we avoided the iron-clad logic of themed galleries; nevertheless, a number of themes that were significant for the era should be obviously present: globalisation; interest in public space; diverse ‘gaze strategies’; social art and art interventions; the subjects of integration and nationalism; various forms of feminism and forms of body art.

E.K.: I would say that the works we selected for the show have not failed us; they represent and reveal all these things very well. It becomes immediately obvious that the 2000s artist created and worked in his or her time, sustaining a dialogue with the reality, its events, problems and sore spots. For instance, a very prominent role is played by the investigative discourse.

Karel Koplimets. Vilde Road Case. 2010/2021

The exhibition foregrounds the new discourses and subjects, as well as the new media. Did showing these works demand special solutions ‒ huge efforts of conservation and restoration, of reconstruction (for the installations) to exhibit them in their original state?

E.K.: Reconstruction is an expensive luxury; we could only afford it within reasonable boundaries. We selected a number of key works and restored them.

T.T.: Two of the major projects were installations. The only thing that had survived of Jevgeni Zolotko’s ‘Grey Signal’ (first shown at eponymous exhibition at Vaal Gallery in 2010) was the video; the tangible part was made again from scratch. The second project demanding some heavy-duty reconstruction was Karel Koplimets’ ‘Vilde Road Case’ (first shown at eponymous solo exhibition at Tallinn City Gallery in 2010), of which only the paper-based material had survived ‒ photographs, newspaper clippings, etc. Alongside these two, we also had to restore from scratch Edith Karlson’s ‘Peeing Woman’ (2007/2021) and the ‘Portable Angle of Hate’ (2005/2021) installation by Marco Laimre.

We did not exclusively stick to the principle of showing only pieces that had physically survived since that decade; our approach was quite liberal in that we also accepted new versions of the old works. For instance, many artists had transferred their photography series to the Diasec technology; it is a method of face-mounting prints on acrylic sheet and it was not really done in the 2000s. But the 2000s were a decade of conceptualism. Yes, a number of artists were dynamically working in terms of materiality, but it does not mean that the lost pieces cannot be restored.

Edith Karlson. Peeing Woman. 2007/2021

What are the 2000s that we remember like? How does it correlate with the art of the decade?

E.K.: Memories are definitely tied to certain political and economic developments. The first half of the 2000s is associated with unseen economic boom, and I would like to hope that it did influence the artists as well. It was, for instance, very difficult to go study abroad, in the West, and yet everybody did it ‒ which means that it was achievable. Alongside the economic boom, the decade was also marked by emergence of active feminism.

T.T.: Another phenomenon I associate with the 2000s is the success story of the developing digital technologies. And yet it does not feature that prominently in our exhibition for the reason that the first projects by Timo Toots and other artists who explored the subject of media transformations and mapping of the digital world per se in their works are not in working condition anymore today ot perhaps a restoration to their original state does not seem practical. Besides, these works were not intended to remain in working condition on the site for eleven months running without any additional technical maintenance. Technology is essentially a rapidly aging area, and the same danger applies to any art that employs technology. And it is for this reason that some subjects that were very much relevant in the 2000s are not represented in our exhibition.

E.K.: The artists who worked with digital media back then have by now gone so far in their projects that it would even be embarrassing to show their first baby steps in that direction.

To what extent subjects and media that were topical in the 2000s are still important to us today? What has become outdated? And what has, quite the opposite, proved to have come before its time?

T.T.: We should single out social-critical art here, which was a very significant phenomenon during the decade. It does not work anymore in its original form today, although I would not say that it had become outdated.

E.K.: This fight has already transferred to the institutional and ministerial level, the way it happened, for instance, regarding the problem of the social security, an issue that was first raised in the 2000s. The appearance of Marge Monko’s ‘I Don’t Eat Flowers’ (2009/2011) was an earth-shattering event. It was a statement of the fact that the artist today is practically a destitute person who lives below the poverty line, because the minimum wage in Estonia was higher than the annual income of an artist. And that now the artists should fight for their rights ‒ fight with the state, with the institutions. And so a strong movement of institutional criticism emerged in Estonia, because it was the exploiters of the artists ‒ museums and other institutions ‒ that were to blame. As a result of this fight, museums now pay the artists royalties for taking part in exhibitions. Of course, a museum whose funding has not been significantly increased by the state cannot become the place where problems like sickness insurance funds for the artists could be solved. But the museum has always supported the artists’ fight for their rights.

On the one hand, the fact that the artist is essentially paying the state for being allowed to make art was articulated very clearly in the 2000s specifically by female artists. What followed was the emergence of all kinds of activists who are demanding today ‒ and rightly so ‒ that their work be reflected in the general picture as well. On the other hand, institutional criticism, the artists vs. the museum. It is a movement that has been well recorded in Estonia. And so I believe that our exhibition offers a very good insight into the processes of the time. We are not hiding anything; all the frictions have been named and exposed.

Marge Monko. I Don’t Eat Flowers. 2009/2011

T.T.: You touched upon the subject of art media. The 2000s were an incubator for today’s art scene to an even greater extent than the 1990s were. The activities of the Department of Photography of the Estonian Academy of Arts and the resulting upsurge of photographic art; development of the medium of installation art ‒ all of that happened in the 1990s, and yet the 2000s were the time when it became a sort of norm in Estonia. We see that there is no fundamental difference with the situation today. Yes, the subjects and the focus change with time, but it was back in the 2000s that the key position of installation art and photography was established back.

E.K.: Conceptual investigative photographic art ‒ under Marco Laimre at the Department of Photography of the Academy of Arts ‒ was the dominant trend; it made it possible for the artists to assume a certain investigative position.

T.T.: Yes, exactly. Also the influence of documentary art, which was very important at the time. In some cases the artist started making documentaries, like Jaan Toomik; in other cases the artists used archive footage-based films as a research tool, and so on. Documentary art is a concept that has not become completely obsolete: it was at its peak in the 2000s but it has become part of the norm today.

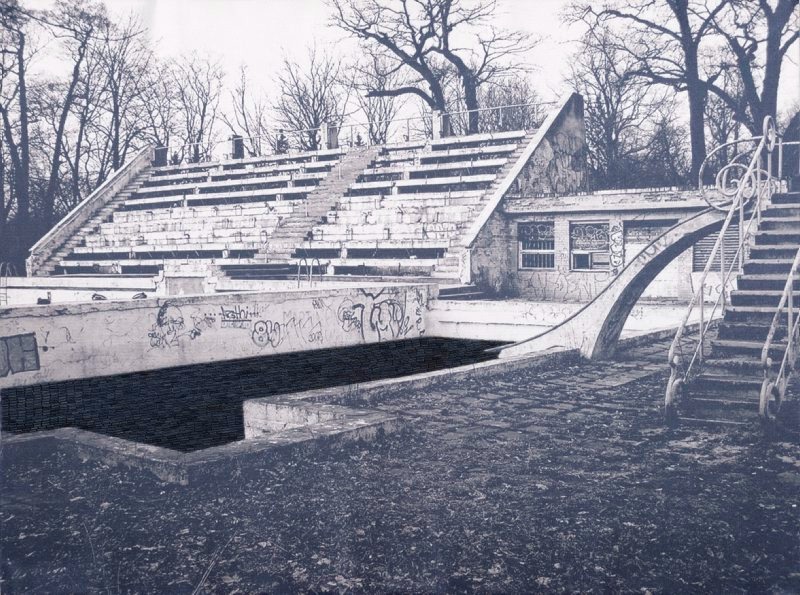

Jaanus Samma. Swimming Pool 7. 2005

Speaking of norms ‒ how far from the 2000s has today’s art departed?

T.T.: It is probably more focused on matters of form an material today; political engagement has somewhat receded to the background. There are very few intervention actions and works tackling uncomfortable subjects today. As I see it, the 2000s picture was much more diverse; today’s scene is dominated by the mainstream.

E.K.: It was very much about the artist taking an active, even aggressive position, feeling free to say something like: Fuck this, the Estonian government is not taking care of this, this and that! All of these activism-driven positions formed during this comfort zone period, when, in the context of the general economic boom, is was finally possible to speak openly about the meagre funding for art, because the government could not very well come up with excuses like ‘Oh we’re so poor’ at the time. Which was nevertheless what it did, using the tired old rhetoric and not taking advantage of the new opportunities to normalise our art life.

Marco Laimre. Portable Angle of Hate. 2005/2021

What was the role of Estonian art of this period in the Baltic and also global context?

E.K.: You could say that it was much more modest than in the 90s when our fantastic video artists earned international acclaim. It is the price you pay for local activism: as soon as you turn your attention to your local affairs, your art loses its wider focus, one that the rest of the world would also find interesting. The focus did not matter greatly to the rest of the Baltic countries, and I am afraid that only a few individual works would strike a chord with the international viewer.

T.T.: We asked our colleagues from the Centre for Contemporary Art to look up in their records which Estonian works did the most travelling in the 2000s: all of them turned out to be video works from the 1990s. The profile of Estonian art abroad did not really broaden at all during the 2000s: it was still all about the video art from the 1990s...

E.K.: …with its huge poetic images of land and swamp, nature and man. The activist trend of the 2000s is quite local and not necessarily interesting to everybody else.

Kiwa. Black Square Fade. 2008

Please name the work you find the most emblematic of the 2000s.

E.K.: I would pick the ‘Black Square Fade’ installation (2008) by Kiwa. In 2015, the whole progressive art world was marking the centenary of Malevich’s ‘Black Square’ (1915); all sorts of representative exhibitions and expensive shows were being mounted all over the place. And they all became targets of critique, because what was on show was not so much Malevich’s art as the commercialisation thereof. How much Malevich’s works cost, how many versions of the Black Square there are, who are they currently owned by, etc. ‒ discussions of this kind were going on all the time. Kiwa, who worked with the Tartu semioticians, illustrated the situation ‒ the transformations of the Black Square ‒ in an extremely interesting way. He printed countless copies of an image of the Black Square on a very good printer with an initially full cartridge that was gradually depleted over the course of the printing and the images were increasingly fading until they became hardly visible at all. Until the printer produced an image of a white square on a white background: the Black Square had completely vanished. This devaluation of the Black Square as one of the most cryptic and enigmatic works of art is taking place in front of the viewer: he or she sees with their own eyes how the square dissipates as if dissolving in time and space. I am always very happy to put this work on view because this is one of the rare cases of Estonian art activism staging an intervention on a subject that belongs to global art. Kiwa’s work is a genuinely generous gesture: look at what is happening in the world ‒ look at them run around with the ‘Black Square’.

T.T.: I would highlight the ‘Project for Paldiski’ (2006‒2013) by the Johnson & Johnson group. As part of the project, residents of the town of Paldiski, the birthplace of the sculptor Amandus Adamson, one of the first professional artists of Estonian extraction, were offered an opportunity to pick a sculpture for the urban environment. It would be a replica of one of three sculptural works by Adamson. Paldiski, a ‘closed city’ in the Soviet era and a port town today, is largely defined by its somewhat specific public spaces. Furthermore, the population has distanced itself from politics almost completely, having lost any hope of their voice making a difference. The project gave these people new hope that there would be an actual result if everybody will exercise their right to have a say. There was a massive vote, and finally the sculpture was indeed erected. The whole programme and the life of the local community that developed around it truly has a great emotional impact.

E.K.: ‘Project for Paldiski’ does an excellent job of recording the conflict of interest that emerged between the community and the local government these people had actually elected themselves, as well as the increasing enthusiasm of the local people who really embraced the idea. There is a genuine communicative social element to it ‒ we see them constantly considering the initiative and making their own suggestions. When they find it hard to agree on one of the three sculptures, there are all sorts of arguments. It is very interesting to observe the process.

Johnson & Johnson. Project for Paldiski. 2006–2013

T.T.: On the one hand, it is an intervention kind of work, an attempt to emancipate these people, to give them agency in matters that have to do with their own life. At the same time, humour also plays an important role here; it is not an extremely serious documentary that would move you to tears. Besides, a certain role is also played by the mock-up produced in China and the whole issue of public space. ‘Project for Paldiski’ weaves a whole range of subjects that are significant for the decade into an integral whole while also painting a vivid portrait of a community which no-one cares to work with and to which no-one has ever paid any attention.

I think that the most interesting bit was people explaining their choice. There were some genuine moments of art analysis there. People open up as personalities when they try to substantiate their view of which sculpture would represent their town best: they may be giving some thought to their identity in a wider sense of the word for the first time in their life. It is an excellent portrait of the residents of the town, of the whole era and the place: the artists have truly captured it very well.

E.K.: ‘Project for Paldiski’ does a good job of speaking about social problems ‒ how badly these things have been handled before and how they really need to be tackled now. I would make viewing this film compulsory for all these institutions, schools and classes dealing with integration where they keep repeating the same things over and over again. Everything depends on the people ‒ give them a chance to make things right. As per usual, by the way.

It is an example of empathetic social art that still works today.

T.T.: Adamson’s sculpture helped view the situation through a completely different lens. And, of course, a lot of it hinges on the personalities of the artists: their skills of communicating with people, establishing contact with them is really their forte. I consider it a unique case that deserves special attention. ‘Project for Paldiski’ also foregrounds a whole string of concepts that are key for the decade: documentary film, social criticism, monuments, as well as various national communities, paying attention to them and searching for shared goals to solve the problem of polarisation of the society.

Title image: Jevgeni Zolotko. Grey Signal. 2010/2021