Visions of the Future That Inspire and Support Us Today

About the exhibition Futuromarennia. Ukraine and the Avant-Garde / On view from April 8 until September 10, 2023 at the Kumu Art Museum (Tallinn)

Something unprecedented took place in the Kumu Art Museum’s exhibition programme this April: since July of the the previous year, the Kumu team had been working on preparing an exhibition which they couldn’t be fully sure would even happen until just a couple of weeks before its planned opening. The exhibition Futuromarennia. Ukraine and the Avant-Garde (08.04.–10.09.2023) was being prepared in cooperation with Mystetskyi Arsenal (Kyiv) in very extreme circumstances, i.e. the Ukrainian colleagues were working in a war zone and experiencing constant air raids and shortages. The decision to adapt the exhibition Futuromarennia, which had closed in Mystetskyi Arsenal only a few weeks before the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion, came about due to both ethical and professional reasons. The wish to express solidarity with Ukrainian colleagues and art institutions by offering protection to a valuable part of their heritage went hand in hand with the intention of introducing to a broader audience the phenomenon of radical innovations and truly inspiring experiments of the avant-garde age in Ukraine. Showing to the public the admirable large scale and variety of aesthetic synthesis of the Ukrainian avant-garde movement, which in large part was appropriated by Russia’s own brand of avant-garde, is an opportunity to decolonise Ukrainian art history. Critical decolonial thinking today, the self-identification of Ukrainian artists one hundred years ago, and the everyday reality of current employees working in Ukrainian art institutions were the topics that exhibition curators Olha Melnyk and Ihor Oksametnyi discussed with Elnara Taidre, the exhibition’s coordinator, in the following conversation.

Elnara Taidre: I must start by sharing some emotions – my colleagues and I admire the strength of the spirit of the Ukrainian nation and the contribution of museum workers in sustaining it. We are not only in solidarity with you, but are also very keen to learn much more about the history, culture, and art history of Ukraine. At the Kumu Art Museum we are very excited to be showing the exhibition Futuromarennia, which first took place about a year ago in Mystetskyi Arsenal in Kyiv (15.10.2021–30.01.2022), and we are really intrigued in how it will be modified specially for Estonia. At least in Tallinn, the art-loving public is keeping their fingers crossed that everything will go as planned. Could you please introduce the concept of your project, which is also reflected in the neologism of its title? And what are main differences between the Kyiv and Tallinn exhibitions?

Olha Melnyk: I will start by sharing my emotions as well. We are also impressed by the permanent support that is being given to Ukrainian art colleagues by the museum community all over the world. We are greatly thankful to the Kumu Art Museum for the opportunity to introduce Ukrainian culture in Estonia despite the difficulties associated with the risks of war due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. It is quite incredible to start cooperating with an institution in a country where military actions are taking place – even at our small organisational level, when as a result of Russian missile attacks, electricity and internet connectivity disappeared in the winter. This, of course, caused disruptions in communication with our colleagues. At that time, no one could guarantee that the exhibition would take place. It is difficult to express how valuable your human warmth and professional solidarity is for us.

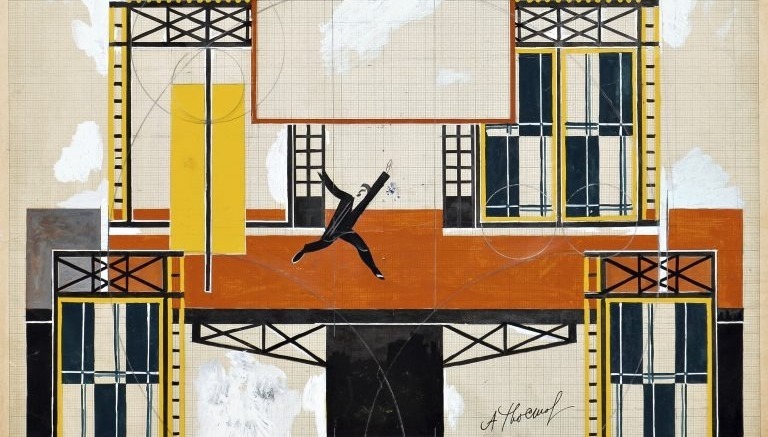

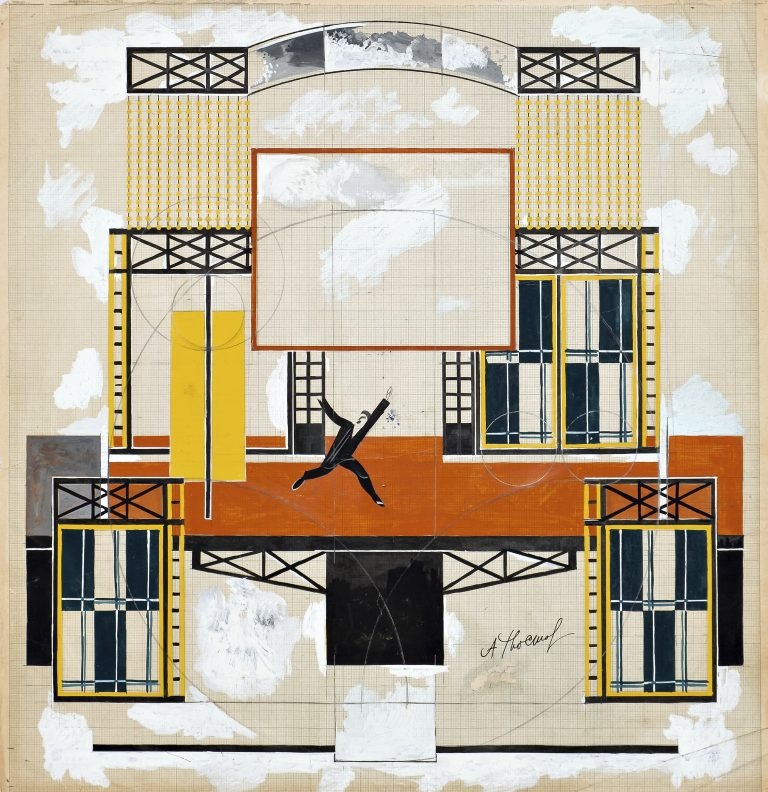

Oleksandr Khvostenko-Khvostov. Stage design for the play Mob, adapted from Upton Sinclair’s novel They Call Me Carpenter. Ivan Franko Theatre, Kharkiv. 1924. Mystetskyi Arsenal

I would like to note that despite having seemingly common content, the Kyiv and Tallinn projects have significant differences. This can even be seen in the names of the exhibitions; for instance, in Kyiv it was Futuromarennia, whereas at the Kumu Art Museum it is called Futuromarennia. Ukraine and the Avant-Garde. In both cases, we are talking about Futurism not as an artistic movement, but as an idea. However, the exhibition for the Kumu Art Museum was created in the context of new world developments. The full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine fundamentally changed the emphasis. Therefore, in my opinion, the word “Ukraine” is the keyword in the name of the Tallinn exhibition. Artistic content becomes, to some extent, a tool that we use to tell about ourselves. The post-colonial option is of great importance. Unfortunately, in today’s tragic events we observe too many direct historical analogies with what happened a hundred years ago. Thanks to international projects, we are able to resist the Russian invasion, which includes attacking our culture as well.

Ihor Oksametnyi: First of all, thank you for your words of support. Needless to say, it is important to us and inspiring. The main difference between the Tallinn exhibition and the Kyiv exhibition, which was held in nine halls of the Mystetskyi Arsenal with a total area of about 4,000 square metres (nearly 500 exhibits from 30 sources were presented there), is not only their differing scale. The Kyiv exhibition continued a series of exhibition projects of the Mystetskyi Arsenal dedicated to the cultural processes in Ukraine in the first decade of the 20th century. Before that, the topic of Futurism in Ukraine had not yet been visualised in such a format. To some extent, that had been due to the fact that the concept of Ukrainian Futurism is, first of all, a literary phenomenon. We tried to present the influence of this phenomenon on various spheres of culture of that time by emphasising the manifestations of Futurist ideas in visual art, theatre, architecture, cinema, design... We thought it was very important to emphasise the fundamental ideological differences between the phenomena, i.e. Futurism in the territory of Ukraine – the Hylaea group founded by David Burliuk, the circle of artists from the city of Krasnaya Polyana, and Mykhail Semenko, the leader of Ukrainian Futurism and whose name this movement is usually associated with.

We started preparing the exhibition project for KUMU when the Russians had already begun their attack. The statistics on the destruction of our cities, villages and their cultural objects change every day. Now we are talking about thousands of destroyed objects of cultural infrastructure. We realise that the current war is also a war for cultural heritage, for our identity. The Ukrainian resistance is a response to the Russian propagandist narrative about a single nation. That is why the theme of Russian terror is more active in this exhibition. And we also tried to emphasise the self-sufficiency of the Ukrainian version of Futurism.

What were the main sources of inspiration for the Ukrainian Futurists? The first impulses came from Italy, the homeland of Futurism, with the credo of a new urban culture that abandoned traditions. But was it possible to fully follow this path in Ukraine, with its great culture of rural life and extremely vital folk art?

OM: I‘ll talk about the broader background. We can assess many artistic movements in the early twentieth century whose representatives positioned themselves as innovators: Fauvism, Cubism, Orphism in France, Vorticism in Great Britain, Der Blaue Reiter in Germany, and so forth. Such diversity reflected the state of modernised Europe – the technical revolution and urbanisation required new artistic forms. Each of these innovators called for an end to the old in many ways. Marinetti not only criticised his predecessors but also called for the radical destruction of their heritage. Undoubtedly, artists in Ukraine also sought renewal and were well aware of European trends. Artistic experiments were actively developed here.

It is worth mentioning the most important projects of the Ukrainian avant-garde artists. In the spring of 1906, paintings by Davyd, Liudmyla, and Volodymyr Burliuks, for example, were presented at an exhibition in the hall of the Kharkiv Nobles Assembly. The exhibition Lanka, which took place in November 1908 in Kyiv, presented the works of Oleksandr Bohomazov, Volodymyr and Davyd Burliuk, and Oleksandra Ekster. In December 1909, the sculptor Volodymyr Izdebsky organised the International Exhibition of Paintings, Sculptures, Engravings, and Drawings in Odesa. He visited Munich, Berlin, Rome, and Paris, involving Georges Braque, Henri Matisse, André Derain, Gabriele Münter, Henri Rousseau, and Paul Signac. The Burliuk brothers, Oleksandra Ekster, and Vasyl Kandinsky were also represented there. With 746 works in total, 141 artists took part in this action that reflected the diversity of modern art of all directions, from academicism to impressionism.

All these actions were extremely critically perceived by the public, which had grown up on classical models of art. We cannot talk about the transformation of avant-garde trends into the artistic mainstream in the 1910s. And that is understandable. On one hand, Ukraine remained mainly an agrarian territory with a traditional cultural background, but Futurism was the art of “machines and cities”. At the same time, artists were well aware of European trends here: some of them, such as Vadym Meller, studied in Europe, and some, such as Oleksandra Ekster, travelled a lot. There was therefore an active exchange of ideas. And even being under the influence of European innovations, Ukrainian artists perceived them not as dogma, but as an impetus for experimentation. The synthesis of Cubism and Futurism gave life to Cubo-Futurism, for instance.

On the other hand, the influence of local tradition cannot be overlooked. I could name here a unique example of the interaction of avant-garde and folklore in the workshops of the villages of Verbivka and Skoptsi, where embroideries were created based on the sketches of Kazymyr Malevych, Oleksandra Ekster, and Nina Henke-Meller. In turn, the folk artists Vasyl Dovhoshyia, Yevmen Pshechenko, and Hanna Sobachko-Shostak, who worked in these workshops, also resorted to unprecedented artistic experimentation to find new types of artistic embroideries. It is also worth admitting the interaction with the historical context and the influence of steppe archaism of prehistoric times and the art of Rus'-Ukraine or Ukrainian Baroque. The creative work of the world-famous sculptor Oleksandr Arkhypenko is marked by the plasticity of Scythian idols, and even the name of the Futuristic society “Hylaea” was taken from The History of Herodotus and was connected with a local toponym.

IO: The revolutionary nature of Mykhail Semenko’s work can be seen in how he modernised Ukrainian lyrics with urban themes, his bold experiments with the form of the poem, and his introduction of new images and created words designed to reflect the new industrialised age. Therefore, we consider him the first urbanist poet in Ukrainian literature. Naturally, his statements, manifestos, and experiments could not but cause a negative reaction, a scandal, in the literary environment. After all, a scandal is an indispensable component of a Futurist movement in any country.

In the phenomenon of avant-garde in general, I find one of the most fascinating aspects the urge for synthesis, the ambition to redesign the world via the new aesthetics of the total work of art. Among the exhibits in your exhibition, I can see examples of at least two types of synthesis. The first is an all-embracing visual aesthetic that can be applied to all visual, material, and spatial objects – from painting to scenography, from costume to architecture. The second is the synthesis of very different mediums and forms of art – painting and poetry, theatre, and cinema. What would you name as the most remarkable examples of these forms of artistic synthesis?

ІО: Yes, you are right; the creation of a synthetic work of art that would simultaneously affect all spheres of perception – sight, hearing, touch and even smell – completely came from the main ideas of Futurism. It was laid out in several manifestos of the Italian Futurists of the 1910s, and was later reflected in what was called parole in libertà (words at large), and in the case of the Ukrainian Futurists – poezomaliarstvo (poetry-painting). These are complex works where the boundary between image and word disappears, and letters perform not only a grammatical function but also an associative one. The principles of syntax, the very foundations of a literary text, were destroyed. Sound imitations, shifting images, inventing “ingenious” innovations, etc., and the latest technical achievements of printing were used. Poetry-painters were very concerned about both the visual and auditory perception of their texts, as their work was related to the latest changes in thinking.

In the Futurist literature of this period, visual poetry was most clearly manifested in the work of Mykhail Semenko, who published two collections of “poetry- paintings” – Kablepoema za okean (Cable-Poem Across the Ocean, 1920–1921) and Moia mozaika (My Mosaic, 1922); and in the prose work of Andriy Chuzhy – The Bear Hunts the Sun (1927–1928). Cable Poem for the Ocean is a synthetic work, the full meaning of which can be understood only if all its eight interconnected parts are taken into account. We tried to convey the principle of poetic painting in the installation video, where the actors read Cable Poem by Mykhail Semenko. Vasyl Yermylov’s reliefs of the 1920s, in particular, his Harlequin, presented at the exhibition, is an example of the artist’s search for synthesis. It is something in between a picture and a construction – if you like, an object. By the way, the name of this work was given by the art critic Ihor Dychenko, who bought this work and in whose collection it was before it was handed over to the Ukrainian state. Dear Ihor Dychenko, forgive me, but, in my opinion, the name Harlequin does not correspond to the spirit of this work. In my opinion, it is obvious that this is Vasyl Yermylov’s replica of Pablo Picasso’s Guitar series. Sorry for the digression.

Vasyl Yermylov (1894–1968). Harlequin. Pictorial Relief, 1924. Oil on wood / Mystetskyi Arsenal

OM: You’ve perfectly described the tools of creating a synthetic form through the combination of elements of painting, poetry, theatre, and cinema. At the same time, cinematography appears to be the most synthetic genre. It simultaneously combined literature, painting, theatre, and music. Ultimately, cinema became the personification of the epoch of modernisation as a productive technological art and it attracted representatives of the current avant-garde, primarily Futurists. Almost all prominent figures of the 1920s collaborated with the All-Ukrainian Photocinema Administration (VUFKU). It was engaged in the production of films, possessed cinema factories (studios) in Odesa and Kyiv, and issued the magazine “Kino”. Semenko was in charge of the script department of VUFKU, and the Futurists Heo Shkurupii, Yurii Yanovsky, and Mykola Bazhan were involved in the writing of film scripts. Almost all the artists of todayʼs exposition collaborated with VUFKU – directors Marko Tereshchenko and Les Kurbas, and artists Oleksandr Kosarev, Vadym Meller, and Anatol Petrytsky. The Ukrainian cinema of the 1920s is a separate fascinating topic. The Oleksandr Dovzhenko National Centre in Kyiv will offer a film programme dedicated to avant-garde cinema as part of our project at the Kumu Art Museum.

However, artists didn’t only synthesise different mediums, they also synthesised approaches and methods of very different fields. Avant-garde artists wanted to be theoreticians and researches: they worked like scientists in their studio-laboratories. But with their experiments and investigations, they attempted even more than achieving an “objective” scientific outcome – they wanted to attain a universal aesthetic and philosophic values. One such representative of the Ukrainian avant-garde was Oleksandr Bohomazov – can you please talk more about his theory of the four elements of art and his method of experimentation?

ІО: It is difficult to explain Oleksandr Bohomazov’s theory in an interview. In short, in his treatise, he considers the interaction of the Object, the Artist, the Picture and the Spectator. He carefully describes the meaning of the four main elements of painting – Line, Shape, Colour and Picture Plane. He analysed how each of these elements affects the viewer’s perception of a work of art. Vasyl Kandinsky and Kazymyr Malevych were dealing with similar problems around that time. And after the First World War, the emotional aspect of colour became the subject of systematic research by the German Bauhaus.

OM: Zhyvopys i elementy (Mystetstvo zhyvopysu) (Painting and Elements: (Art of Painting)) was Oleksandr Bohomazovʼs theoretical treatise written in 1914. In this work, he de facto substantiated the principles of avant-garde art at a time when the term “avant-garde” itself did not exist. This book was not published during the author’s lifetime. It was preserved by the artist’s wife, Wanda Monastyrska, and then by the Central State Archive-Museum of Literature and Arts of Ukraine. It was published only in 1996. “Art is an endless rhythm, the artist is its sensitive resonator,” said Bohomazov, and explained the interaction between reality, the artist, and the viewer. The picture in this triangle acts as a medium in the transmission of aesthetic experiences from the artist to the viewer who transforms the system of symbols encoded in the picture into his own experience. The artistic perception of reality provided by a work of art is built through the four simplest elements: Line, Shape, Colour and Picture Plane. This was, in fact, the explanation of Cubo-Futurism.

Could you please choose a particular artwork from your exhibition and give it a more detailed analysis, so that our readers can have a magnified glimpse into your Futuromarennia laboratory?

OM: The most interesting issue in the process of preparing the exposition, indeed, is the identification of relationships and the construction of interaction between individual works and elements. The most difficult challenge for me, in particular, was to visualise the differences between the art of the 1910s and the 1920s. It obtains quite different specifics despite all the identities of the ideas. It was necessary to focus on the political factor, which was decisive for the realisation of Futurist aspirations. In addition to the political coup, there were devastating and extremely rapid economic and social developments in Ukraine after World War I. Futurism received a real grounding from its motto of “Metropolis, Machine, Mass”. Rapid industrialisation led to extreme urbanisation, and traditional trends were defeated by innovation and modernisation. The visitor of the exhibition should feel all these innovations through the works. A laconic visual message was required. We chose two dominant pictorial works for this exhibition. The first is Viktor Palmovʼs Ukrainian Village in Winter, which reproduces the traditional way of life. The second is Solomon Nikritinʼs painting A Trip Around the World, which represents the delusions of a bright future created by the revolution, a sentiment characteristic of the young generation in the 1920s.

Viktor Palmov (1888–1929). Ukrainian Village in Winter, 1920. Oil on canvas / Mystetskyi Arsenal

Solomon Nikritin (1898–1965). Travel Around the World, 1918–1920. Oil on plywood / Mystetskyi Arsenal

IO: I would also like to say something about Vadym Meller. He was an active supporter of “cultural synthesis”, a programme that was supposed to unite architecture, theatre, cinema, space, and enlightenment. In the mid-1920s he was quite famous in Europe. In 1925 he participated in the epochal Art Deco exhibition in Paris, which gave the name to the entire style. There he was awarded a gold medal for his stage design of the play Secretary of the Trade Union by L. Scott of the Berezil Theatre. In the same year, his works were exhibited at the international theatre exhibition in New York. The Futuromarennia exhibition will present several of his works, including sketches of costumes for the ballet Assyrian Dances for Bronislava Nijinska’s studio, with whom the artist worked from 1919 to1921; they are unique in terms of the perfection of Cubo-Futuristic plasticity, lines, and silhouettes. These are some of the best examples of his style, the characteristic features of which were elegance, sophistication, and balance. The internal dynamics of movement in outwardly static, as if sculptural, majestic figures is transmitted through the rhythm of geometric planes.

Vadym Meller (1884–1962). Sketches of male costume for the ballet Assyrian Dances

School of Movement of Bronislava Nijinska, Kyiv

1919. Watercolour and gouache on paper / Mystetskyi Arsenal

Without a doubt, preparation of the exhibition Futuromarennia took place in very extreme conditions. What is the everyday reality of the work in your institution and other museums during this time of war? I know that Mystetskyi Arsenal is continuing to make exhibitions, proposing to the citizens of Kyiv to deal with their emotions through the art experience – I can see from your webpage that you have a rather regular exhibition programme!

ІО: We continue our activities, including exhibition activities, as much as it is feasible.

OM: This situation is extreme and tragic for many of us. The everyday life of Ukrainian museums is currently determined by their distance from the frontline. The Russians turn museums under occupation into institutions for propagandising the values of the so-called Russian world. Outwardly, it resembles pictures from the Soviet epoch, and they’re returning to the same narratives and ideology. It is difficult to believe, but they are erecting monuments to Lenin in the occupied cities. A terrible picture of cultural destruction is revealed in the liberated territories. The Kherson Museum of Local History, for instance, participated in our Kyiv project, but it was completely looted during the occupation. The occupiers simply destroyed the valuable items that they could not physically take out. The entire collection from the Kherson Art Museum was also removed.

Another story concerns the museums located close to the frontline. The fate of the city of Kharkiv, located only 40 kilometres from the border with Russia, is particularly tragic. Starting on 24 February of last year and up until today, it has been an object of continuous bombardment. Significant damage was caused to the premises of the Kharkiv Art Museum in the first days of the invasion. Its exhibition had not been dismantled at this time; this museum preserves the most powerful art collection, from Ilya Repin to Vasyl Yermilov. At the same time, the resilience of our colleagues in Kharkiv is amazing. I will give you a typical example – the fantastic Kharkiv Literary Museum has been holding a literary festival, while under military attack, for almost a year.

Kyiv is relatively detached from the frontline now, but there is a constant threat of missile strikes. At the same time, in my opinion, the war suddenly forced us to completely change our attitude towards many things that were familiar from an earlier time. Culture and art became the focus of public attention. In the community’s way of thinking, the losses that our culture is suffering seem only to have added even more value to it. Invasion did not cause apathy; on the contrary, it revived interest in cultural events. The news brings lots of announcements of exhibitions, festivals, and theatre premieres taking place in the warring country every day. I will tell you how it looks from the inside. Under the threats of air raid alarms and emergency power cuts, visiting the exhibition at the Mystetskyi Arsenal becomes quite a challenge for the public. You should constantly follow the organiser’s messages on social networks to be sure that the exhibition space is accessible, and in case of a missile threat, escape to the shelter. In winter, when the missile attacks were most destructive because of the lack of heating, the exhibition space was sometimes available for only two hours at a time.

In June 2022 we resumed our public activity with the Exhibition about Our Feelings. It happened almost immediately after the retreat of the Russian occupiers from the Kyiv area. But developments at the frontline remained extremely uncertain. Let’s be honest – all of us were trying to survive mental exhaustion. And we were looking for psychological medicine for ourselves, for the team of the Mystetskyi Arsenal. We just gathered together: someone was returning from abroad, someone came from a relatively safe part of Ukraine, someone had experienced being under occupation, and someone had survived the shelling in Kyiv. It was a new, different and tragic experience that we wanted to share with each other. We talked endlessly, and it was therapeutic for all.

This was the main reason we decided to create an opportunity to talk about our personal shock to other people – a kind of storytelling through communication in the space of the exhibition. In this way, the Exhibition About Our Feelings came to be from a collective intuition. Our purpose was simple and clear – to support the shocked people who at that time were looking for such support in their respective practices. The concept of the exhibition or the exhibited works was not of great importance. The project rather looked like a humanitarian action, a countermeasure to the dehumanisation caused by the war. At the same time, we would not like to focus exclusively on the trauma, or seemingly cherish this pain. The search for new meanings that have become evident as a result of the war was more important.

Our new exhibition, Heart of the Earth, features the agricultural land of Ukraine as the granary of continents, the backbone of global food security. This topic became relevant after 24 February, when Russia blocked the supply of food from Ukraine to other countries throughout the world. The exceptional role of Ukraine as the breadbasket of the world has become apparent to people in different parts of the globe, and us as well. Our colleagues are working on a new project that will be held in April. In addition, in June we are going to renew our beloved Book Arsenal Festival. A few years ago it was recognised as the best book festival in Europe.

Undoubtedly, our insistent and unwavering position is to not only survive physically during wartime, but live a full intellectual life as well.