Otherness, Desire, the Vernacular

An interview with Carlos Motta and Jaanus Samma

Otherness is a long-standing subject of various emotions ranging in intensity from curiosity and attraction to hostility and repulsion. Although the concept of “the norm” appeared relatively recently, the idea of a moral convention is as old as the first complex organised societies of Mesopotamia. What is interesting, however, is how those conventions (re)defined the cultural context around themselves. The attitude towards otherness within the discourses of power, social class, and religious imagery profoundly defined the moral outlines of society. This exhibition brings together the works of Carlos Motta (b. 1978, Colombia) and Jaanus Samma (b. 1982, Estonia), both dealing with the representation of difference and the historical relation to the “other” in societies.

Carlos Motta. Photo: Cory Rice

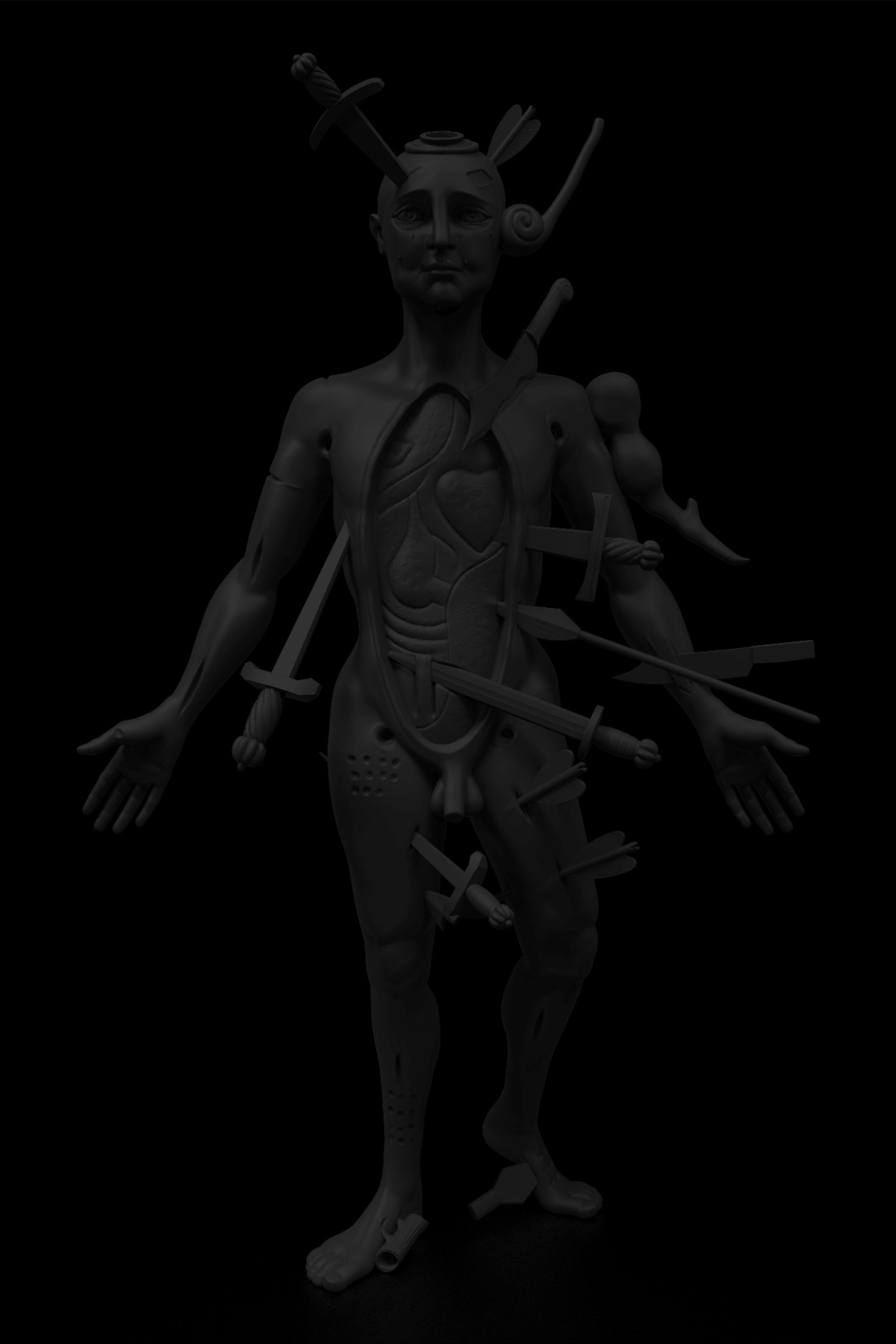

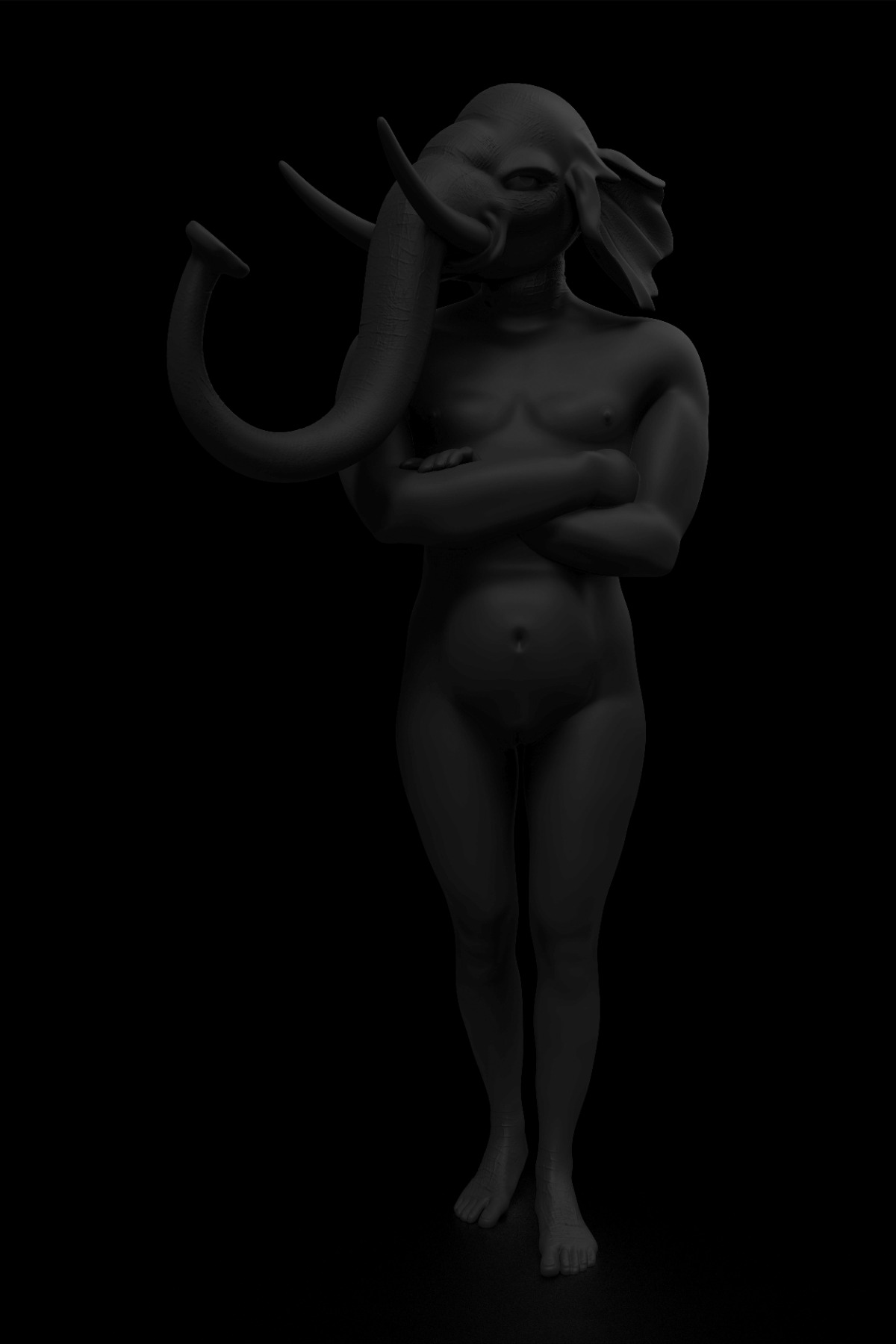

Motta’s practice documents the narratives of so-called minority communities, including those defined by sexual and gender politics. The exhibited works are part of the series The Psalms (2018). These works are based on illustrations from the late Middle Ages to the Late Renaissance, and present comprehensive inventories of “curiosities” from the animal (including the human) world. For example, the sculpture Vir marinus episcopi specie (2018) is based on the illustration from Conrad Gesner’s Historiae animalium (1551). Other sources include Fortunio Liceti’s De Monstris (1665) and images familiar in medieval surgical texts from as early as the 10th century CE. The representation of otherness in these texts communicates mixed emotional and aesthetic states, out of which the desire for the subject by the author or authors of the manuscripts is the most fascinating. The encyclopaedic manuscripts filled with various wonders were common among knowledgeable and wealthy elites in that period’s Christian and Islamic worlds. Historians still argue about the aesthetic reaction to difference: was it primarily repulsion and fear, or desire and wonder? The Psalms is a particularly fascinating series because it evokes the unresolved response to otherness in religious, epistemological, and social discourses.

Jaanus Samma. Photo: Martin Rünk

Samma’s artistic research primarily addresses the history of sexuality and social relations in vernacular cultures. Books and paintings, as mediums of knowledge and sacred objects, were considered a backbone of cultural capital throughout the last millennium. Everyday objects and household artefacts of the lower classes of society became interesting for researchers only in the previous century along with the advent of critical theory and social micro-history. In the exhibition, the artist presents a speculative interpretation of queer desire expressed in the language of a traditional Estonian household. The prints juxtapose symbols of gay culture, such as jockstraps, with the iconography of conventional craft. The tapestry used to be a centrepiece of the house as an iconic representation of ideal domesticity. Samma offers an imaginary reading of simple living in the village from a homoerotic perspective, indirectly posing a vital question: what do we know about simple living outside of the grand narratives of heteronormativity, where the “other” was fetishised or loathed?

In dialogue, Motta and Samma’s works offer a fresh outlook on the treatment of otherness on different levels of society. Pushing the boundaries of the knowable, they dare to challenge the preconceptions about the notions of difference and desire and present them as layered, diverse, and complex “objects” that require constant and scrupulous re-examination.

The joint exhibition of Carlos Motta and Jaanus Samma, Otherness, Desire, the Vernacular, curated by Denis Maksimov, was running from November 19, 2021 until January 16, 2022 at Temnikova&Kasela gallery in Tallinn.

Exhibition view, Carlos Motta and Jaanus Samma ‘Otherness, Desire, the Vernacular’. Photo: Roman Sten Tõnissoo

D (Denis): How did you first learn about each other’s work?

C (Carlos): I learned about Jaanus’s work through a common friend and colleague, Italian curator Eugenio Viola, who curated Jaanus’s Estonian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2015. Eugenio, who has also curated projects I have been involved with, recognised commonalities in our interests and approaches to the inquiry and representation of hidden queer histories. Eugenio put us in touch and since then, Jaanus and I have kept each other informed on our respective work. I was pleased when Jaanus invited me to think about this two-person exhibition at Temnikova & Kasela Gallery in Tallinn.

J (Jaanus): I first saw Carlos’s work in 2015 at the Future Generation Art Prize exhibition organised by Pinchuk Art Centre in Kiev. His approach to the local context left a deep impression. We met at around Christmas of the same year. I remember that Carlos had just come back from Europe on the same day we were supposed to see each other in New York, and he was very generous to meet up even though he hadn’t slept for ages.

Carlos Motta,Vir Marinus Episcopi Specie,from the, series The Psalms,2018, 3 D print,acrylic photopolymer plastic,spray paint

Carlos, when did the idea of working with the representations of otherness in European medieval and renaissance books emerge? Was there something particular that triggered your interest?

C: The Psalms is one amongst a series of my artworks (Towards a Homoerotic Historiography (2014), Beloved Martina (2016), etc.) in which I investigate the representation of ‘otherness’ in pre-modern times through working and re-interpreting old artefacts, drawings, and sculptural objects. These works seek to understand the ways in which sexual and gender variance, disease, and disability were often represented as differently-abled creatures, monsters, and often non-human and anthropomorphised bodies.

Jaanus, the speculation of “other” life in places where it is not presumed to exist seems to play an important role in your work. How is the conversation between fiction and historicity laid out in your practice?

J: Fiction is often a helpful tool when we want to talk about things that are not part of mainstream or official historical narratives. The lack of materials, records and sources is the reason why fiction has a prominent role in queer history, but thanks to its playful nature, it has many advantages, too. Fiction has its own truth and sometimes it can give us a much clearer image of the past than some historic documents.

Jaanus Samma, Jockstrap with a Black Waistband, screenprint, wooden frame 65x65cm, 2021

Jaanus Samma, Jockstrap with a Blue Waistband, screenprint, wooden frame 65x65cm, 2021

Jaanus Samma, Jockstrap with a Red Waistband, screenprint,wooden frame 65x65cm, 2021

Both of you approach the density of social imagery and the dynamic role that various “others” play in it – somewhat helping to flesh out the notion of a norm in a particular historical period. Do you think the dialectics of “normal” vs “weird” (or “queer”) can be conceptually reconciled in a non-violent way? How?

C: The histories of sexuality and gender identity have taught us that the signaling of “the other” as different and dangerous has mostly been a violent pursuit throughout time and in various cultures. Thankfully, in some parts of the world there are growing discourses of respect and recognition of difference, where being queer is a tool of empowerment and not a source of shame. Ideas around visibility, self-determination, and self-representation have provided ways to think and learn about different sexualities, gender identities, and ways of living that reject normative standards of morality and (sometimes) legality. I am confident to say that Jaanus and I have both contributed our part to these cultural and societal transformations through our artworks.

J: The norm is a social construct that is an abstraction by definition. There is no single person who fully represents the norm as we all deviate from it in one way or another. Queerness or queering as an act does not contradict the norm, but undermines and reinterprets this construct. Paradoxically, the norm is constantly changing, and in the end, it is up to everyone to decide how and in what direction it moves.

Carlos Motta, Wound Man, digital C-print, 101,6x66,04cm, 2018

Carlos, why did you decide to use black and monochrome colours for your prints and the sculptures?

C: The use of black monochrome for the figures and backgrounds was both a formal choice and a way to address ideas of (the lack of) visibility and opacity regarding the representation of “other” bodies.

Jaanus, you often use found objects and vernacular techniques (the wooden bench in this exhibition and weaving of the wool carpets, respectively) in your work. What drove your choice in these particular cases?

J: Vernacular techniques have always been of great interest to me, although I don’t do much handicraft myself. We should keep in mind that these old techniques carry knowledge and information in the same way as the images and symbols used on carpets, for example. Works made in old techniques create a connection with history and help to better understand and reconceptualise the past.

But the meaning of historical objects also changes over time, and the new context allows us to see familiar objects from a new angle. If we take ethnographic artefacts, for example, I think their representation has been very one-sided and I consider it a lost potential. Vernacular culture is so rich and meaningful that we need to apply many different approaches to really gauge its depth.

Jaanus Samma, Bench with a Rug. Installation, wool, wood, 2021

Intersectionality of otherness turned out to be strongly emphasised in your duo exhibition with my curatorial intervention. What aspects in your dialogue (both in preparation for the show and its result) do you find most exciting?

C: I enjoy the conversation proposed by our two bodies of work and how these two specific projects inform each other. Together, these works provide ways to think about how the imagination of certain bodies has been contingent with specific cultural traditions, which in part are influenced by religious beliefs, legal apparatuses, and social and biological sciences.

J: I like the contrast that emerged between our works in this exhibition. Carlos’s works are like dark revelations from the depths of history, and my works seem unexpectedly festive and colourful. The series of Psalms by Carlos does not offer a clear interpretation for these characters nor the attitude the chroniclers had towards them. They are distanced, dim, inaccessible, yet present. My works are about a past that is less removed and about simpler people. The works have less awe and more colour and warmth.

Carlos Motta, Of the Aegopithecus, digital C-print, 101,6x66,04cm, 2018

Does cultural context from your perspective affect how the norm approaches otherness in a particular society? You both came from and currently live across the oceans from each other, and I wonder how your dialogue played out from the comparative point of view.

C: I think Jaanus and I are interested in the cross-cultural similarities around the discrimination of diverse sexualities and gender identities. We are also interested in proposing new readings to those histories from contemporary queer perspectives and in providing tools to construct new critical discourses around the recognition of difference. While there are certainly particularities to how cultures have dealt with queer people—such as the impulse to control, disempower, and change them—is more often similar throughout the world.

J: My research is mostly local. I do specific case studies because it is important for me to understand the context that I am working with. However, during the production phase, it is important for me to generalise the topic in a way that is understandable and comprehensible to a wider audience. Ideally, the work does not only carry information but also represents some more general values and ideas. In this context, it does not matter from which continent the artist comes from or whether the work deals with medieval manuscripts or carpet traditions from Western Estonia. It is about being open to all human experiences no matter their historic or cultural circumstances.

Carlos Motta, Figure of a man with an elephant head, digital C-print, 101,6x66,04cm, 2018

Title image: Exhibition view, Carlos Motta and Jaanus Samma ‘Otherness, Desire, the Vernacular’. Photo: Roman Sten Tõnissoo