Pop-folklore tricksters smashing stereotypes

Sonja Yakovleva and Nicholas Grafia. Type / Cast / Thrill at the Temnikova&Kasela Gallery

Maria-Helen Känd

The Temnikova & Kasela Gallery exhibition where the works of two Germany-based artists meet – one, Sonja Yakovleva of Russian origin; the other, Nicholas Grafia, from the Philippines – draws its power from images widespread in popular culture and their ability to reinforce stereotypes related to race, ethnicity, gender and sexuality. The artists’ bold and expressive style critiques social power structures and calls on viewers to ask themselves a candid question: what roles do we play in everyday life, and wouldn’t it be interesting to step out of them for a change?

The English-language exhibition title Type / Cast / Thrill brought me up a little short, as it could have been translated into Estonian to make it more accessible for Estonian audiences. Anyway, the conceptual core of the exhibition is indeed typecasting in the sense of the Hollywood film industry and certainly also anywhere else that actors are offered one specific type of parts. Typecast characters are based on certain traits – age, gender and skin colour. Typecasting can also mean a process where the public comes to overly associate an actor with a specific role (like Emma Watson with Hermione Granger).

Sonja Yakovleva and Nicholas Grafia. Type / Cast / Thrill, 2021, installation view. Photo: Roman-Sten Tõnissoo

From martyr to playing with oneself

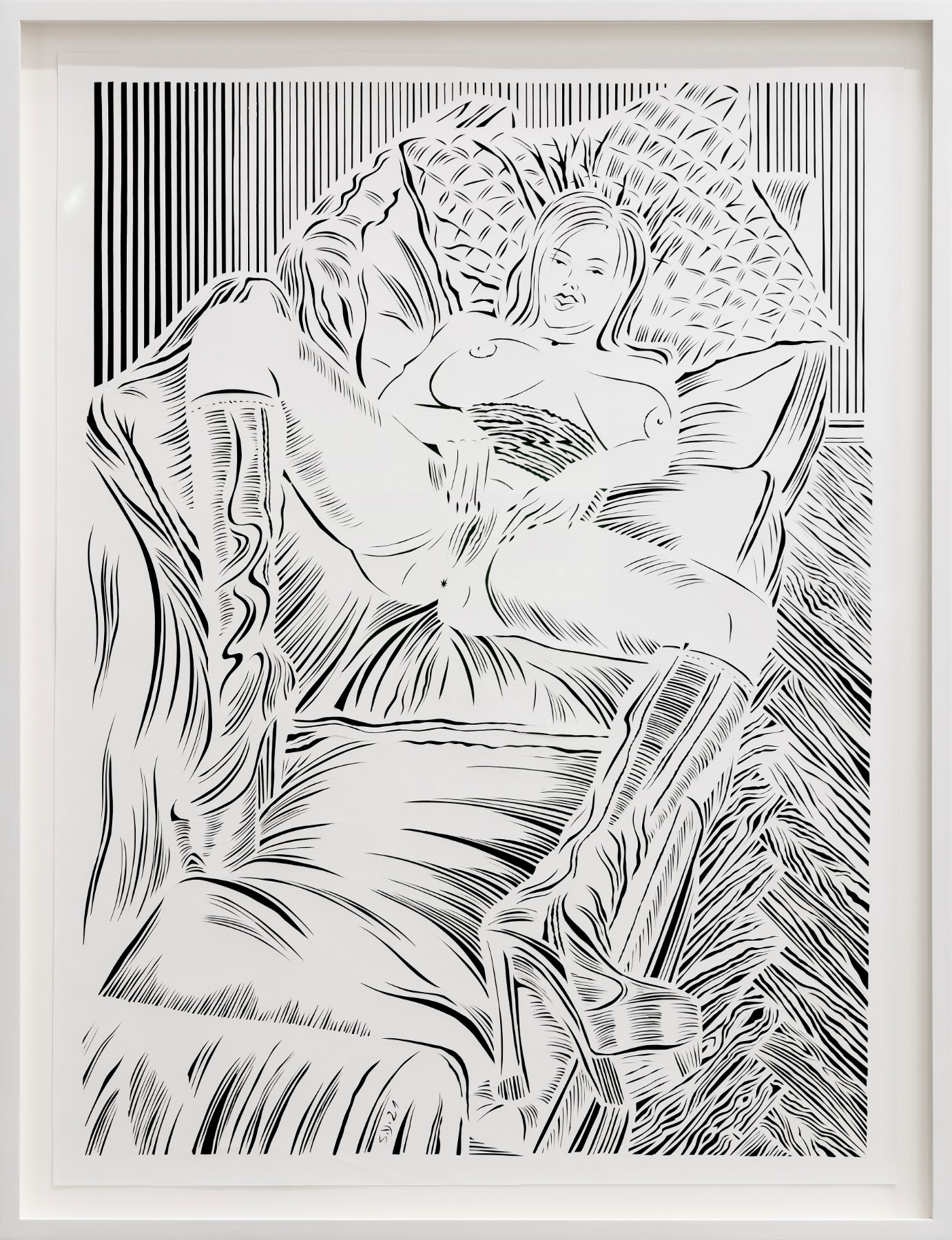

Entering the gallery and encountering Yakovleva’s papercutting of a nude woman with a come- hither look, legs spread, I’m struck with an odd revulsion and recognition. This picture captures my own experience with the burden of being female and questions related to self-depiction and self- determination. Why am I overcome by a feeling of shame when women are exhibited in a sexualized way? What are my expectations for how women are represented in visual culture? Should I be that prim and proper girl who doesn’t allow too much of her sexuality and beauty to shine (lest I not be taken seriously) or would I prefer to live my many identities and reimagine my roles in a different way?

Nicholas Grafia. Gaze Face II. Digital painting digitally printed on alu-dibond, 220x145 cm, 2021. Photo: Roman-Sten Tõnissoo

Such complexes associated with gender stereotypes were expressed astutely by Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, who said “the problem with gender is that it prescribes how we should be rather than recognizing who we are”1. Especially considering, as Adichie put it, “we teach girls that they can’t be sexual beings in the way boys are”. It is the possibility of the latter that Yakovleva signals by representing women as erotic, free and powerful, or in her earlier work, as athletic and muscular “power women”.

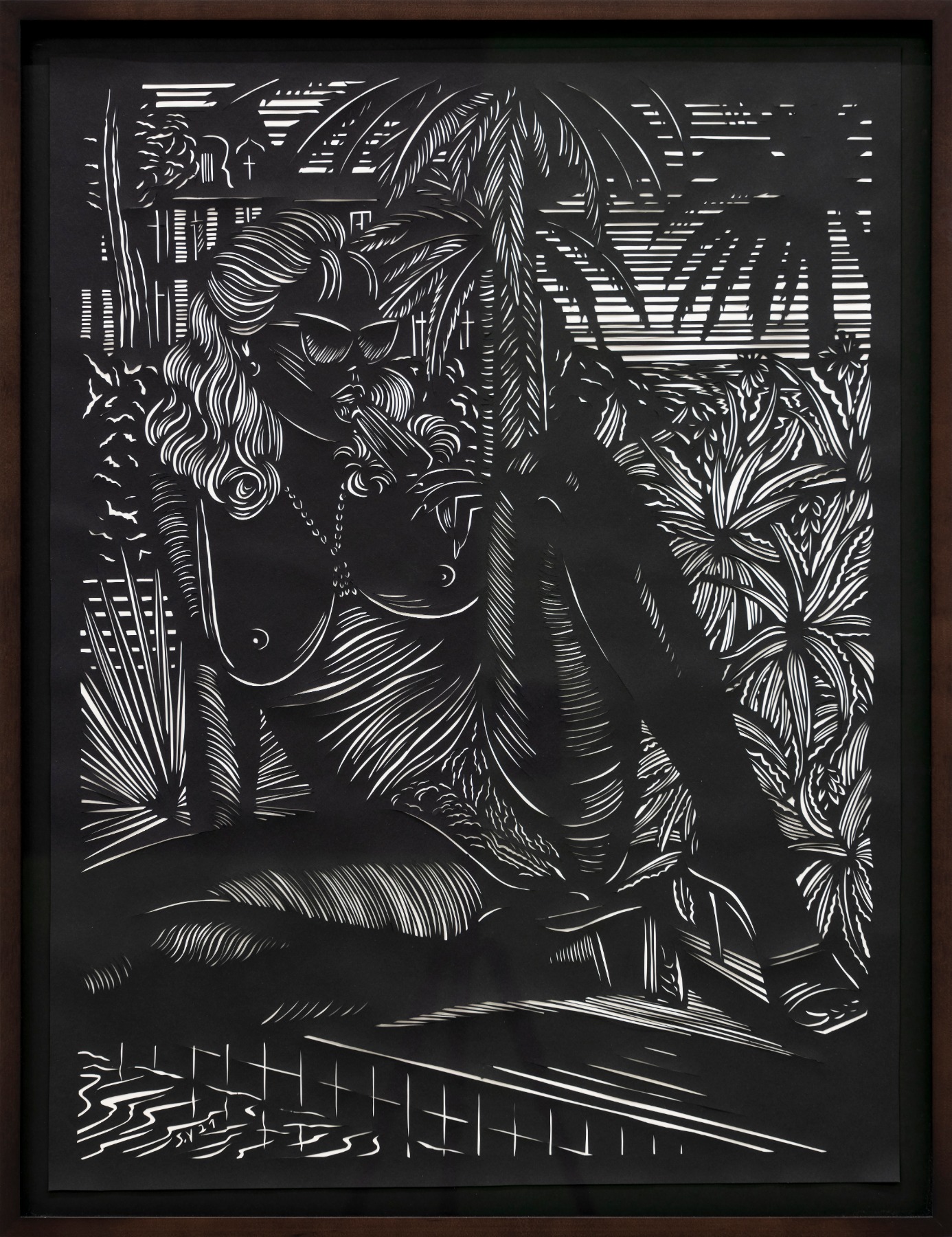

The contrast between intricate approach to paper and powerful corporeal images in the artist’s works illustrates that everything contains both yin and yang energy at the same time. The white cuts made into mostly black paper in turn deconstruct racial binaries, because through the interplay between figure and backlighting, silhouette becomes prominent instead of skin colour. It’s interesting that in the 19th century, papercutting was considered the domain of women, seen more as a handicraft than the “serious” discipline of painting practised by men. Yakovleva’s astonishingly fine detail and virtuosity shows how papercutting confidently claims a place for itself in the contemporary art canon.

Looking back at history, experiments that reconceptualized womanhood became prominent in the feminist projects of the Sixties and Seventies – take Womanhouse (1972) or Difference: On Representation and Sexuality (1984). During the same period, avant-garde artists such as Penny Slinger with her Surrealist photo collages or Hannah Wilke with her self-portraits wrested back control and liberty to depict the female body. In Yakovleva’s works, through the integration of sexualized clichéd images of women that have been proliferating in the media into her artistic practice, women go from being a martyr to a person who plays with herself (double entendre intentional), which could free her of internal tensions and social expectations. Yes, women belch and self-gratify themselves and there’s no reason to feel bad about it. Yet feigned shame is very wont to arise even in the 21st century thanks to the resounding alarums from archconservatives.

Sonja Yakovleva. Festival de Cannes. Paper-cut, 2020. Photo: Roman-Sten Tõnissoo

The monumental and detailed scene in the middle of the gallery presents an alternative female role in grandest fashion. Here the artist depicts a red carpet sprawling in the Cannes Film Festival jungle, which in the post Me Too and, perhaps no less so, ecofeminism-inspired atmosphere of the climate crisis, has been taken over by women. Instead of offering a typical view of the European nude tradition through the male’s perspective, in which women play a passive role2, Yakovleva’s characters add up to something more like the gaggle of women and trans women populating Almodóvar’s All About My Mother who let their sexuality be freely expressed and aren’t bashful about emphasizing their physical attractiveness.

Sonja Yakovleva. Festival de Cannes, detail. Paper-cut, 2020. Photo: Roman-Sten Tõnissoo

Nevertheless, it’s understandable that this sort of female gaze on women – which recasts the male gaze, but retains the sexualisation – won’t necessarily have a liberating and empowering effect on everyone. Not everyone equates womanhood with femininity (otherwise we’re back in the trap of constructs) but with the freedom to interpret one’s gender in precisely the way that they are personally closest to. So, the detail and concreteness of Yakovleva’s works made me feel some trepidation – if semi-pornographic images in women’s Instagram posts or female artists’ music videos are a turnoff, why should it be any different in a gallery?

Sonja Yakovleva. Try to Figure Out Who I Gonna Fuck This Week. Paper-cut, framed, 80x60 cm, 2021. Photo: Roman-Sten Tõnissoo

From the critical cultural theory view, the question of representation of women at the exhibition is thus settled in the sense of representation as advocacy or politics (vertreten) but the door is still open to a possible polemic in regard to the ways of depicting women (darstellen).3 This range of problems was expressed by the American women artists’ group Guerrilla Girls with their famous poster (1989), which asked whether women have to be naked to get into a museum.

The answer in our own era of inclusive curating is hopefully a “no”, but if women want to depict themselves naked, naturally they have free rein to decide otherwise. Yakovleva’s position in this sense is certainly provocative and protest-minded. She is a pop-folklore trickster who revels in razzing virtuousness and virginality.

Sonja Yakovleva and Nicholas Grafia. Type / Cast / Thrill, 2021, installation view. Photo: Roman-Sten Tõnissoo

What do pictures want from us?

Non-identification with stereotypical roles and the experience of cultural Otherness lies at the heart of Grafia’s works as well. His striking, expressive paintings are monstrous, the antithesis of cosiness, because the artist uses strong symbolic language to tell stories with threads of racism, gender discrimination and class violence, partially stemming from his personal experience as a migrant of Philippine origin. In this way, the artist creates a mood that is dark in spite of his bright use of colour, and which beckons in terms of its intellectual and emotional weight.

Grafia, who is also a performance artist, puts the body at the figurative and thematic centre, dislocating it from a powerfully real-life image. The characters in his paintings are, variously, emphatically not to scale, limbs in knots, wearing ghoulish masks or seen with distorted faces. Typically for performance art, elements of the theatrical are also found in his paintings. The scenes usually take place in a heavily distorted everyday setting, such as in bed or in the kitchen in his magnetic 2019 painting scenes. At this exhibition, performativity is found in the consummately captivating painting Cleavage Control with strange limbs that seem like devil’s hands assailing Faust’s soul and body.

Nicholas Grafia. Clevage Control. Acrylic on canvas, 140x160 cm, 2021. Photo: Roman-Sten Tõnissoo

The distorted and ambivalent body images allow the depiction of struggles between different identities that take place inside all of us due to social role-games, as Erving Goffman4 describes. In Grafia’s paintings, we see both archetypal characters and symbols from humankind’s collective pop culture memory melting into one bright play of colour. This penetratingly conveys the mental fragmentation that is especially strongly present in the feeling of Otherness, whether due to gender, race or queer experience.

The companion piece to the bright fire-red painting on the gallery’s opposite wall is the more pastel Dead End Angel, based on a TV series by the now disgraced American comic Bill Cosby. Both depict cast members. In the latter, Lisa Bonet stands, melancholy and listless, her hair caught in a door, wearing a see-through blouse with an eye where a nipple should be. It is an impactful nuance that suggests internalized social power mechanisms that make us look at our bodies from the perspective of socially dominant norms. In another sense, we see the picture’s agency and the question raised by W.J.T Mitchell could be asked: “What do pictures want (from us)?”5 We could add Mitchell’s conclusion that the question of what pictures want is inseparable from the question of what women want – power over the viewer.6

Sonja Yakovleva. Hôtel du Roc. Paper-cut, framed, 80x60 cm, 2021. Photo: Roman-Sten Tõnissoo

The nipple/eye is trained on the viewer and doesn’t allow the question in the exhibition concept to be sidestepped: what roles do we ourselves perpetuate or encourage on a daily basis? As an actor, Bonet was initially in the role of the “good” daughter of Cosby’s sitcom family, but came under criticism from the show’s producers and the public when she branched out into film roles that emphasized femininity and sexuality. The positioning of Dead End Angel with respect to Yakovleva’s monumental papercutting is the best example of the artists’ spatial dialogue at this exhibition, speaking about the possibility of the liberation of a female subject in the context of film and TV industry.

The door paintings done by Grafia using a new technique are compelling metaphors; suggesting that we could pass through them from a film industry that typecasts toward a more diverse era. In the abstract collage-like images on the doors, we again meet Cosby Show cast members. By blending painting and photography, the artist imitates the aesthetic form of TV or movie screen, painting as a critical symbol a mouth that by turns pouts and smiles. For those not familiar with the events around the sitcom, the mouth as symbol could be seen, alongside expressing emotions, as enabling the act of speaking, which poses the question of how much airtime and speaking time is given to repressed and under-represented groups in the media space. And in the light of the Cosby Me Too scandal, it asks how much the truth can be told.

Nicholas Grafia. Dead End Angel. Acrylic and graphite on canvas, 140x160, 2021. Photo: Roman-Sten Tõnissoo

Conversation between the artists

It felt fresh to enter a gallery that was divided into halves instead of the familiar four-cornered solution. It made it possible to include more works and get the two artists speaking to one another more naturally. At the same time, the gallery has been used to its full limit with no room to spare. Considering that both of the artists have an edgy signature style and their works need some free space around them, I imagined that merely having two solo exhibitions would also be totally justified.

The problems of typecasting would be one-sided, if treated only from the feminist viewpoint. I am glad that Grafia’s paintings brought a complement to the whole in the form of Black pop culture criticism, and demonstrated how painting as a medium in the technological age is capable of powerfully conveying identity politics and social positions.

In the Estonian art field, as active as it is in smashing social constructs from the feminist perspective, I long to see more international rebels who deal with gender issues together with class and race questions. There is still the tendency in Estonia to think that BLM is some imported subject even though many foreigners with different origins now live in Estonia and our collective consciousness is saturated with Hollywood films and hip-hop. It’s that attributed role we should really be looking at as directly as possible, even if big naked vaginas and deformed black bodies are shocking at first. After all, we shouldn’t be able to greedily feast on global mass culture yet remain blissfully ignorant when it comes to the very real problems related to it.

Sonja Yakovleva and Nicholas Grafia. Type / Cast / Thrill, 2021, installation view. Photo: Roman-Sten Tõnissoo

Sonja Yakovleva and Nicholas Grafia. Type / Cast / Thrill, Temnikova&Kasela Gallery, through April 4

***

1 Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s TEDx talk “We should all be feminists”, 2013.

2 John Berger, Ways of Seeing: “Men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at. This determines not only most relations between men and women but also the relation of women to themselves. The surveyor of woman in herself is male: the surveyed is female. Thus, she turns herself into an object of vision: a sight.” www.youtube.com/watch=BillFriedmanVideos

3 A reference to the terminology used in the essay “Can the Subaltern Speak?” by postcolonialist Gayatri G. Spivak, drawing on Marx’s Der achtzehnte Brumaire des Louis Napoleon.

4 Erving Goffman, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/

5 W.J.T Mitchell, What Do Pictures Want?

6 Ibid.