How Thomas Hirschhorn Is Doing Art Politically?

Two weeks of this spring the Swiss artist spent completing the «ART=SHELTER» project in Latvia.

Dubulti – is a railway station In Jurmala. Erected in the 1970s this late Soviet modernism building has been recently reconstructed, and now houses an exhibition space of Art Station Dubulti, while performing its primary functions. You can still buy a train ticket here and use it as a shelter when the weather is bad: different areas of our life – its practical and spiritual sides – coexist here in an unusual but constant symbiosis. At the end of April Thomas Hirschhorn (1957), a Swiss artist living in France, opened in Dubulti his “ART=SHELTER” exhibition.

The artist has long been attracting international attention with his ‘Presence and Production’ sculptures, the largest – “Eternal Flame” – occupied a couple of thousand square meters of the famous Parisian art space Palais de Tokyo. It was a whole construction built of cardboard and tires, featuring lectures by philosophers, discussions, poetry readings, concerts, it also had a library, a workshop, a daily newspaper, as well as an Internet cafe and a bar. However overwhelming is the scale, the most important thing for Hirschhorn is to make his visitors participate in the process or a multitude of processes occurring simultaneously in the space created by his imagination and his worldview. After all, Hirschhorn's worldviews affect his work directly.

Art Station Dubulti. Photo: Veronika Simoņenkova

Hirschhorn came to Paris in 1983 to join the well-known French communist graphic design collective Grapus, who considered their graphics as a tool for social and educational work. The integration with Grapus never happened in fact because Hirschhorn was not accepted as one of their creative members as he wanted. This first move was a ‘genius’ failure, a difficult moment, but also, an emancipatory event, that made him think harder and to act independently in the field of Art. “To do my work, to assert it, to fight for it, and to pay the price for it – this is my 'demonstration'! Art is a tool to keep the concentration focused on what counts to me, on what is essential – this means to work politically, different from ‘being political’. To love doing my work is already working politically, because the power comes – and must come – from Love”.

Thomas Hirschhorn. «Too-Too, Much-Much», installation. 2010.

Museum Dhondt-Dhaenens. Courtesy Thomas Hirschhorn

As an artist, he refused to exhibit in his homeland between 2003 and 2007, in protest against Christoph Blocher, the right-wing populist elected in the Swiss Federal Council. He stopped this “boycott only when Blocher lost the elections. However, in his key text “Doing Art Politically: What Does This Mean?” 2008, Hirschhorn took a firm stand against a straightforward interpretation of political engagement: “Today, the terms of ‘political art’, ‘committed art’, ‘political artist’ and ‘committed artist’ are used very often. These simplifications and abbreviations have long since been obsolete. They are cheap and lazy classifications. Not for a second do I think of myself as more ‘committed’ than another artist. As an artist, one must be totally committed to one’s artwork. There is no other possibility than total commitment if one wants to achieve something with one’s art.”

Thomas Hirschhorn. «In-Between», installation. 2015. South London Gallery.

Courtesy Thomas Hirschhorn

In this text, Hirschhorn emphasises the importance of a positive approach to the process of creating art itself: “I can only create or fulfil something if I address reality positively, even the hard core of reality. It is a matter of never allowing the pleasure, the happiness, the enjoyment of work, the positive in creation, the beauty of working, to be asphyxiated by criticism. This doesn’t mean to react, but it means to always be active. Art is always action, Art never is reaction. Art is never merely a reaction or a critique. It doesn’t mean being uncritical or not making a critique – it means being unconditionally positive despite disapproval, criticism, rejection and despite negativity.”

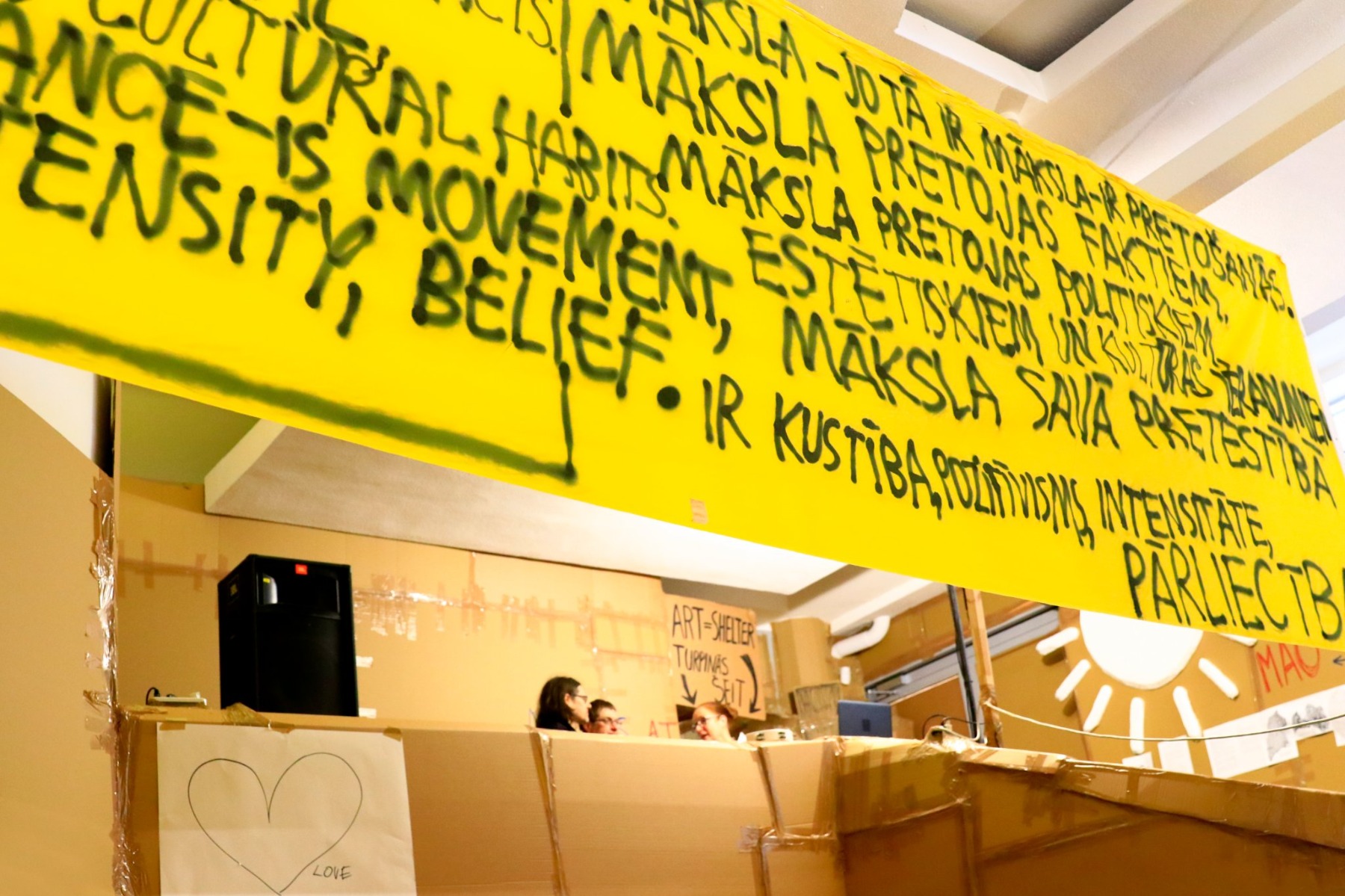

In April of this year, when the war in Ukraine passed its fortieth day, when the Venice Biennale was opening, Hirschhorn was working in Dubulti. On April 24, together with Inga Šteimane – Art Station Dubulti permanent curator – he opened “ART=SHELTER” – “a shelter for hope, production, dialogue, inclusion, love (of art) and exchange; a shelter for preventing hate, anger, violence, negativity, passivity and resentment.” The walls of the art-station Dubulti were completely covered with cardboard with phrases and quotes written all over, printouts and printed copies hanging everywhere; people were constantly cutting some things out, gluing them together, discussing different issues every day and attending different workshops. Things were created and discussed. And for two whole weeks, here was Thomas – a tall man with a crew cut of greyish hair, wearing large framed glasses. Something in his appearance reminded me of engineers or scientists of the 1970s and 1980s. (By the way: “Stalker” by Andrei Tarkovsky is his most beloved film). Restless and positive inventors, who at the same time were sensitive and attentive in perceiving things, in listening to others’ opinions and points of view.

ART=SHELTER is still on for visiting and participating – it will be open in Dubulti until June 25th. Here you can see the fruits of the interaction between the station space, Thomas, his favourite materials and everyone who took part in this positive “creative voluntary Saturday” in “Energy = Yes! Quality=No” spirit. The art-station Facebook account shares the videos of lectures, workshops and discussions held here in April and May. We talked to Thomas on one of the last days of his participation in Dubulti life with his visiting son and family.

View of the «ART=SHELTER» project. Photo: Veronika Simoņenkova

Do you remember yourself as a child?

I remember having a lot of energy, but this energy could not express itself. I was very withdrawn, stuck in myself as a child. I had a normal childhood, the only exception was being an adoptive child.

So all of your craft materials like cardboard, foam, Scotch tape – they don’t come from your childhood?

I remember spending my afternoons lying on a sofa, listening to all sorts of radio programs. I really liked to draw and was quite good at it, but I grew up in a family that had no art in the house, and no interest in poetry, or philosophy. And it took me quite a long time to realise how I could apply my talent, what to do with it. No one in my family encouraged me to do something in a creative field.

I remember how happy I was when I was accepted at the Kunstgewerbeschule in Zürich, (now 'Schule für Gestaltung') – I was by then nineteen-years old – my drawings were appreciated by the jury, according to the results of this tough competition! For the first time I felt some reaction and response to what I enjoyed doing so much.

View of the discussion / «ART=SHELTER» project. Photo: Didzis Grozds

I think you have a very high degree of awareness and responsibility for what and how you do. How did you come to this?

Yes, but not too aware, there is still place for some mystery, for unresolved issues. Some people see themselves as “naturally born” artists, from the very beginning. For me, getting in contact with art was an important step in my own emancipation, a sort of coming-of-age. When I started studying at art school, friends invited me to exhibitions, to openings, and a whole new world unfolded before me. But the real awareness came afterwards, when I was thirty-two, with the decision to devote my life to art, to the history of art. I was also aware that it was not some kind of innate privilege or family tradition, but my own personal thoughtful decision when I was living in Paris after I graduated from art school in Zurich. It was a difficult time for me, in isolation, thinking about what to do with my future.

View of the «ART=SHELTER» project. Photo: Veronika Simoņenkova

Did you change your ways in art then?

I remember visiting an exhibition by Andy Warhol at the Fondation Cartier at Jouy-en-Josas (“Andy Warhol System: Pub, Pop, Rock” in 1990), that showed some of his early works before he became famous, from the period when he was an illustrator and made his slightly kitsch drawings, like butterflies and flowers. This exhibition was truly important for me. I understood that he remained truthful to himself. He pursued what he loved, as in his early works, and took it on a new level. Andy Warhol shows how important it is to be truthful to what is at the core of you. I have always loved collage, so I decided I must stay loyal to this love of mine. I like to read about artists - Joseph Beuys in particular and also Otto Freundlich and Piet Mondrian. These were artists who spent their lives being loyal to an initial idea and therefore created a new form.

Has your understanding of what art can give others changed over time?

I have always wanted to do something that can touch people. Therefore, at the very beginning I wanted to become a graphic designer, I thought they could really influence the world, shape it by drawing posters, making booklets, creating flyers and stickers. I thought they had a direct connection with the audience. But I realised that the very essence of graphic design is always a response to someone's demand.

View of the «ART=SHELTER» project. Photo: Veronika Simoņenkova

I was reading your manifesto “Doing Art Politically: What Does This Mean?” and noticed that art for you is rather a connection, than a reaction to something. You do not response directly, but… what is it you are doing?

I’m trying to give shape to what I believe in, to what needs to be said. Art is a shelter, art is something that can help you, heal you, enforce you. It’s a moment or space where you can exist without hatred, without anger, without passivity. Precisely it’s a moment and a space for being active, for sharing, for believing. This is what I want to do, this is the form of art I want to give.

What are its key elements then?

First of all, ‘presence’. I came here myself in person. I won't be here for the whole duration of the exhibition, but I’m here for the first two weeks, I am present, I initiate the exhibition. Of course, my presence is not the only important thing, it’s the presence of the people who come here.

Then, ‘production’. If you come here, you need to produce something. It can be a dialogue, you can recite a poem, or make a drawing, whatever. And my mission as an artist is to create conditions in which art will be created by others. If I want people to come and do something, I should be the first one doing it here. ‘Presence’ and ‘production’ are the keywords here.

The walls and the floor are covered with cardboard. With this, for example, I want to give a form. ‘Giving Form’ means I need to give, to provoke, to stimulate, or motivate others to do, to add, to contribute, to participate with something of their own.

Thomas Hirschhorn at the Art Station Dubulti. Photo: Juris Rozenbergs

Why cardboard?

For me, cardboard is a politically acceptable material. It is cheap, everyone knows it, it does not have any privilege as a material. It’s universal. I have been working with it for many years. It has a great potential: it's two-dimensional, but you can add the third dimension. Cardboard is a material that has no volume like bronze or marble. It can become three-dimensional but has no volume. I also like it for its “fake” aspect. Sometimes it resembles a “Potemkin village” – you can make anything out of cardboard, simulate anything. For example, people make a cardboard mock-up in a hospital to figure out how to use the space more effectively or find the best distance between equipment. Cardboard is like leather that can be stretched over anything.

I agree! There was also a lot of cardboard at your exhibition Flamme Éternelle at the Palais de Tokyo in the spring of 2014…

There were tires too!

View of the «Flamme éternelle» project. Palais de Tokyo. Paris. 2014. Courtesy Thomas Hirschhorn

View of the «Flamme éternelle» project. Palais de Tokyo. Paris. 2014. Courtesy Thomas Hirschhorn

I just wanted to ask about the tires... For me, these tires were associated with the Maidan, which had just redrawn the course of history, and tire barricades, burning tires became a sign of this emerging reality. Is this association correct?

That’s just one aspect. The main problematic was the space – Palais de Tokyo is a two-thousand-square-meters space without intermediate walls. I wanted to use a material that could divide this huge space without having to build walls. Tire walls are often used in garages. Therefore, I needed tires to separate the space, but at the same time, I valued its porosity, its permeability. We rented and brought in about seventeen-thousand tires to Palais de Tokyo and returned them after the exhibition ended.

View of the «Flamme éternelle» project. Palais de Tokyo. Paris. 2014. Courtesy Thomas Hirschhorn

I remember the exhibition features many philosophical discussions... Apparently, philosophy, a philosophical worldview, is something really important to you?

I wanted to materialise my belief that philosophy, poetry and writing in general, form the skeleton of the world, of our perception of the world. I wanted to dedicate it to my friends, philosophers or poets. I love talking, listening to them. I admire the accuracy of the words they choose and work with. So I decided to have two constantly burning flames for things to happen in parallel, to recreate the atmosphere of conversations around a fire. I invited philosophers and poets to meet and share their ideas about thinking and writing, to pay tribute to the belief in philosophy, poetry and writing.

Reading your texts, one can trace them back to your philosophical views. I would say that your manifesto “Doing Art Politically: What Does This Mean?” is a kind of philosophy for artists...

I felt challenged by the way my friends articulate and express things important to them. So when they asked me: “What are you doing? How would you describe it?” It encouraged me to express myself in writing a text. If I taught at art school, I would tell my students to write down their thoughts – without claims or pretension. I decided to write down what really counts, what precisely is “doing art politically”. Because I often hear “you are an engaged artist”, “you are a political artist”. Writing encourages me to use my own terms, my own language.

It has been 14 years since this text was published. Has your understanding of “doing art politically" changed in any way?

I took this phrase from Jean-Luc Godard. He said that instead of making political films, one should make films politically. He was talking about cinema of course. But what does it mean to do art politically? It means choosing your material, choosing the lights, deciding how to work in space, how to work with three dimensions. And also, what kind of people you engage to help you – everything directly related to your work is political. It’s not about conventional “political art”, it’s not a declamation.

Can politically made art lead to some decisions, to some change?

My dream, and the dream – I believe – of all artists, is to change this world. I have a mission and an ambition. But, I am also aware that it’s a dream, it’s utopian, it’s a dynamic, it’s a goal – it is not a guide to direct action. You don't know how things will turn out, you can only hope – ‘hope’ is the action, because what you do, as an artist, is not just for your own sake. You are connected, you are related to the world. You can't plan the impact of your work, you can only work hard for something to happen. Sometimes a work released many years ago has an influence on someone and if people tell you about it – this is beautiful.

Thomas Hirschhorn. Abschlag, 2014. Manifesta 10, General Staff building, St. Petersburg. Courtesy Thomas Hirschhorn

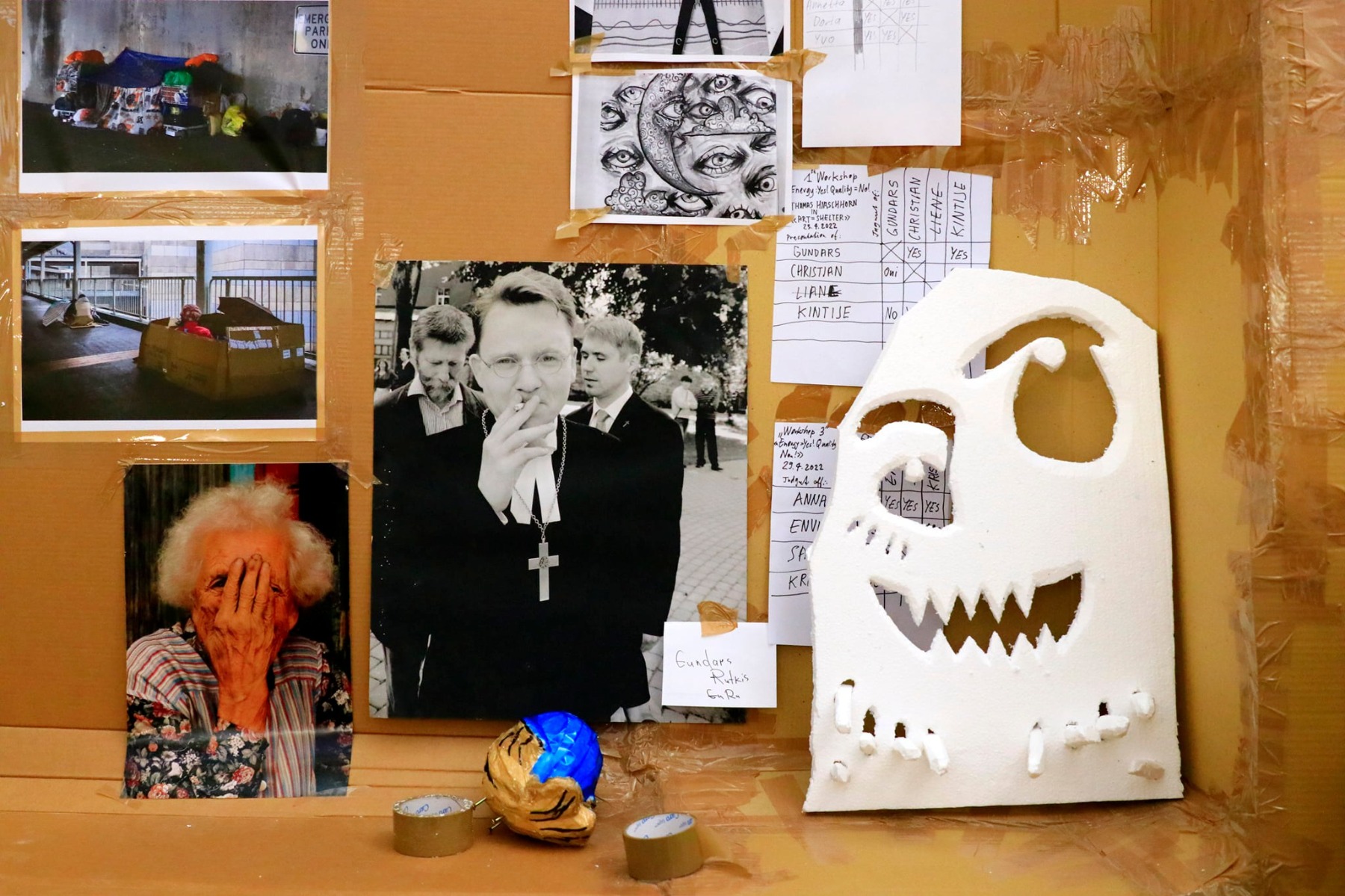

We are sitting next to a makeshift stand with a lot of photos pinned to it – the photos taken at the 10th edition of the Manifesta, a large-scale international wandering art event, held in St. Petersburg, in the Hermitage, in June-October 2014. In the newly reconstructed General Staff building you presented your “Abschlag”. It was a dilapidated, semi-collapsed “building within a building”. Today we see so many photographs from Ukraine with destroyed buildings that were gutted by explosions, this work looks especially relevant. Did you have a similar association when you were working on your “Abschlag”?

Of course, I did not expect such a war to happen in Ukraine. But destruction has always been an important motive for me. I remember 1991, during the Gulf War, discussions with friends about what we should do as artists. Then in 2014 – first came Maidan, then Crimea, and then there was “Manifesta”. Some artists proposed boycotting the exhibition. I said: “No, I have to participate, I have to do the work that would give a shape to this issue.” I’m a fan of Russian avant-garde, so I put on the walls five avant-garde masterpieces (by Malevitch, Rosanova, Filonov) that became visible after the building’s facade had “collapsed”. The work “Abschlag” itself was my response to our discussions and to what was happening. When I visited the General Staff building and its new architecture for the first time, I questioned: “Is this real? Or is it fake? Is it new? Or is it old? Or is it inside, or is it outside? Or is it just bad taste?” I had this idea of making a “Potemkin village” but in reverse, already deconstructed, like a ruin, to counterbalance this very place.

Thomas Hirschhorn. Abschlag, 2014. Manifesta 10, General Staff building, St. Petersburg. Courtesy Thomas Hirschhorn

The boycott issue you mentioned has become relevant again since February 24…

I’m for a boycott that costs me something, that makes me lose something. This is the boycott I recognize. I once made this choice in Switzerland from 2003 to 2007, and it really cost me something. If it doesn't cost me anything, it's not a boycott, there's no meaning or purpose. It’s just an empty, sometimes even opportunistic gesture. Therefore, I am critical of all kinds of calls to boycott.

But what should we do during the war, when war crimes are being committed? What is the mission and function of art in this situation?

This is why I’m here, to do “ART=SHELTER”. It so happened that Inga Šteimane approached me at this very moment and I thought, this could be a good location to work out this idea of art as a shelter. I respect people who go to Ukraine to take up arms and fight for this country, or those who send money and humanitarian aid, or those who help refugees, all those who are not indifferent. Of course, the dilemma is there: should I take up arms myself and fight, or can I create my own work of art, consciously and responsibly, not selfishly in offering the idea of art as a shelter? I believe art fits this concept, as do all artists and people who believe in art. Therefore, to boycott Russian artists just because they are Russian – is stupid. Because real art is always critical to the dominating system, to the doxa and real art is never benefiting from the system, from the doxa, from the dominant.

Art Station Dubulti. Photo: Didzis Grozds

That is, art for you is a refuge, not a weapon?

Art is a weapon. But not to kill others. It’s a protective dome. Because it is art, it’s possible to draw a fine line between declarative terms and real works. Here in Dubulti we carried out Andy Warhol’s famous quote: “Don't cry – work!”, because doing something and sharing it is a weapon. A shelter is quite an appropriate format, you are here with people you don't know, who came in an emergency situation, together. Everyone is doing something: cooking, drawing, studying, reading, resting. That's the idea behind the shelter. Art provides such an openness.

View of the «ART=SHELTER» project. Photo: Veronika Simoņenkova

What will be your next project?

My next new sculpture-project is an exhibition in New York, in Gladstone Gallery representing my work. I will work with cardboard and the idea of mock-ups to present my form of Metaverse in a somewhat ironic way.

The metaverse is a rather abstract and virtual concept…

My work will be real and direct. “Fake it, Fake it – till you Fake it” will be the title of this new work.

In your manifesto, I remember the idea that an artist should remain positive in his work, despite the fact that his work is, in fact, critical of something. How can you stay positive in a world where so many cruel things are happening right now?

Art is a positive gesture, simply because it exists as something no one asked for, without being commissioned. Doing something without an order, at your own will, something that no one expects is affirmative, creative, constructive. That’s why art has such a resistance potential – resistance to negativity, hatred, resentment, confusion. I’m not some kind of positivist in life. But when I’m sad, discouraged or under pressure, I always encourage myself in looking at the artists I love, who, when experiencing great difficulties, continued and persisted with their work, therefore achieving a real breakthrough. Being positive nowadays is a far more complicated task than being negative. And one should undertake the complicated tasks rather than the easy ones.

Thomas Hirschhorn. Photo: Sergej Timofejev

But maybe this positive view comes from our love for the world. You just love it, even if sometimes it seems...

There are so many beautiful and powerful things in the world. Love for art, for poetry, for philosophy, for nature, for other people.

Title image: Thomas Hirschhorn in Dubulti. Photo: Veronika Simoņenkova