Data Intimacy

Interview with artist Anna Ridler

Anna Ridler is an artist and researcher whose works build on a series of connections between natural and technological environments and the analogous relations that human beings develop towards these natural and technological worlds. Through artistic and personal engagement with natural and technological processes, Anna illuminates the similarities between humans, plants and algorithms, thereby bridging the gap between human and non-human existence. Her work Myriad (Tulips) which is at the center of the interview is still on display at the National Library of Latvia until the 11th of November as part of the exhibition Crypto, Art and Climate organized by RIXC.

How should one introduce to the broader public new media art and art that works with AI? What would be your advice?

I guess my advice for both the artists who want to work with new media and the audience would be the same. I think for me, technology is an extension just like any other tool. It is still just a way of working and a process of constructing and understanding the world that we live in. Like anything, its value lies in how you understand it, how you work with it, and how you shape it, rather than just using it for creating a spectacle. It is this spectacle that’s dangerous in new media art – when people look at it and see it just as an image, rather than seeing the history of the media and all of the connotations and associations that sit behind it. That’s why a lot of the debate around whether new media is art or not sits within the framework of conceptual art. For me, when I work with new media, it is in this lineage of conceptual artists who tried to answer larger questions about society and the world.

The work exhibited in the National Library of Latvia at the moment – Myriad (Tulips) – caught my eye, first of all, because of its appealing visual language, which is understandable for a person who isn’t into technological art. The work is sort of in line with more orthodox norms of visual art, which isn’t seen that often in new media art. Do you think it is important to obey orthodox aesthetic principles?

I don’t think it’s important to obey them. In some of my works, I find it interesting to build a relationship with them and see how these principles can be adjusted to this new form of art. So, in the project Myriad and the series of works that developed from it, I was very much trying to look at and reference traditional Dutch still-life painting and bring that language into the 21st century. For me, these connections are very important to have. I think that a lot of my work deals with and translates historical moments through technology. There are these historical aesthetic moments throughout history. So, for me, there is this nice connection that unfolds through visual language, but that’s not to say that it is so for any single piece of new media art. I don’t think it’s important for the field in general, but for me, the visual connection unlocks the historical and contemporary phenomena I’m thinking about.

Tell us a bit more about Myriad – despite its straight-forward visual language, it was rather difficult to unpack all the complex dialogues and connections that constitute the work. Could you unpack some of them?

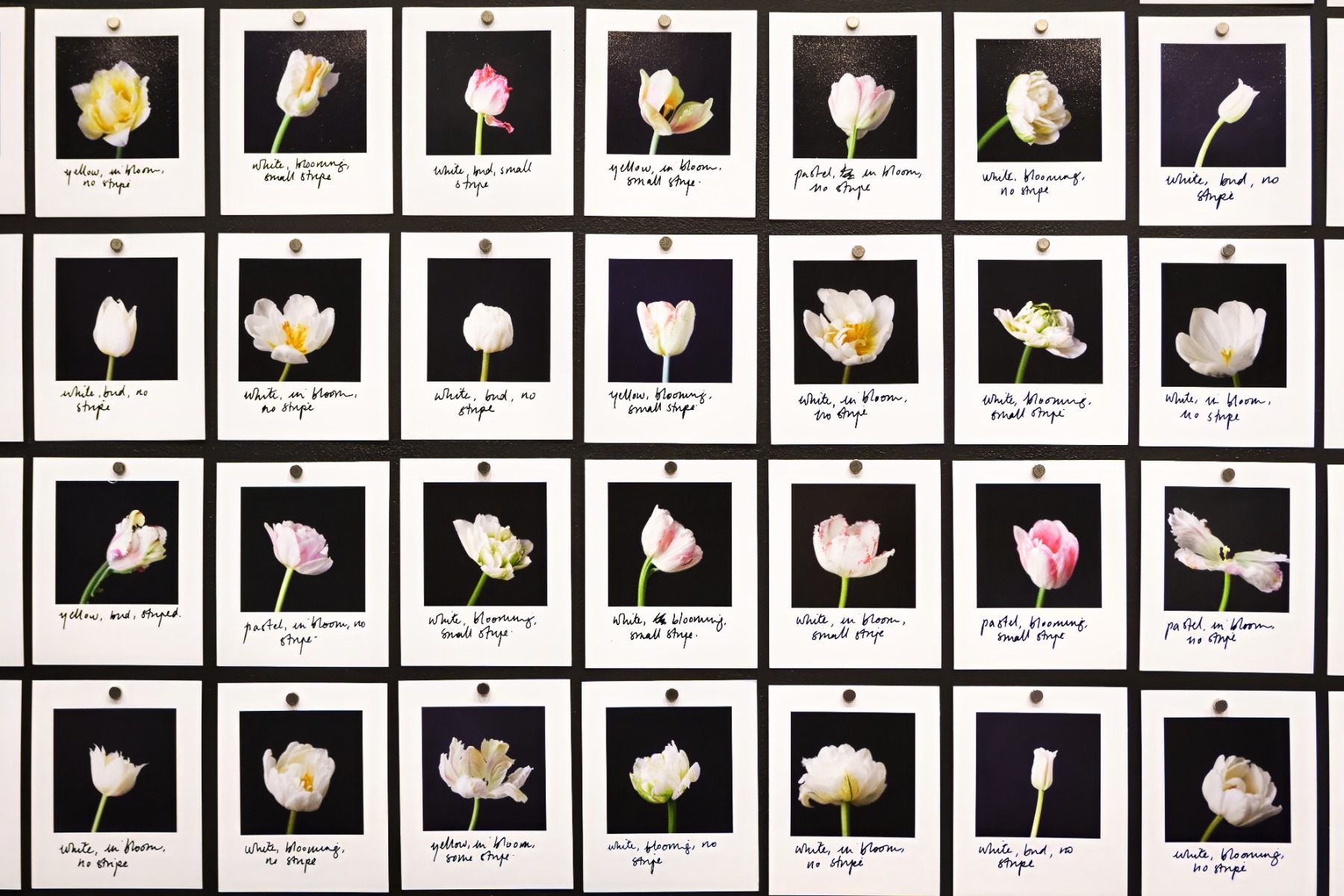

Yes, it is a complex work. For context, Myriad is a visual representation of the dataset that I created in 2018 by taking 10,000 photographs of tulips that I bought as cut flowers while I was in the Netherlands. I used these photographs to create a dataset. Datasets are usually read by machines and used for training machine-learning algorithms. They build up the world that the model can understand. So, if you have a dataset only of cats, the machine or the learning model will only be able to understand the world of cats. It will never understand an elephant and will always produce a cat. So, I created a dataset of 10,000 tulips to create a dataset that could construct a visual of a tulip. I also labelled these photographs to give the model more information so I could control it more. I wrote down which colour each tulip was, whether they were stripey or not, what state the tulip was in – that is, whether it was blooming or dying – and other pieces of information so that it could understand much more of what was in the image. These computers are essentially stupid – they need you to tell them things. They don’t automatically understand what is in the image the way a human does.

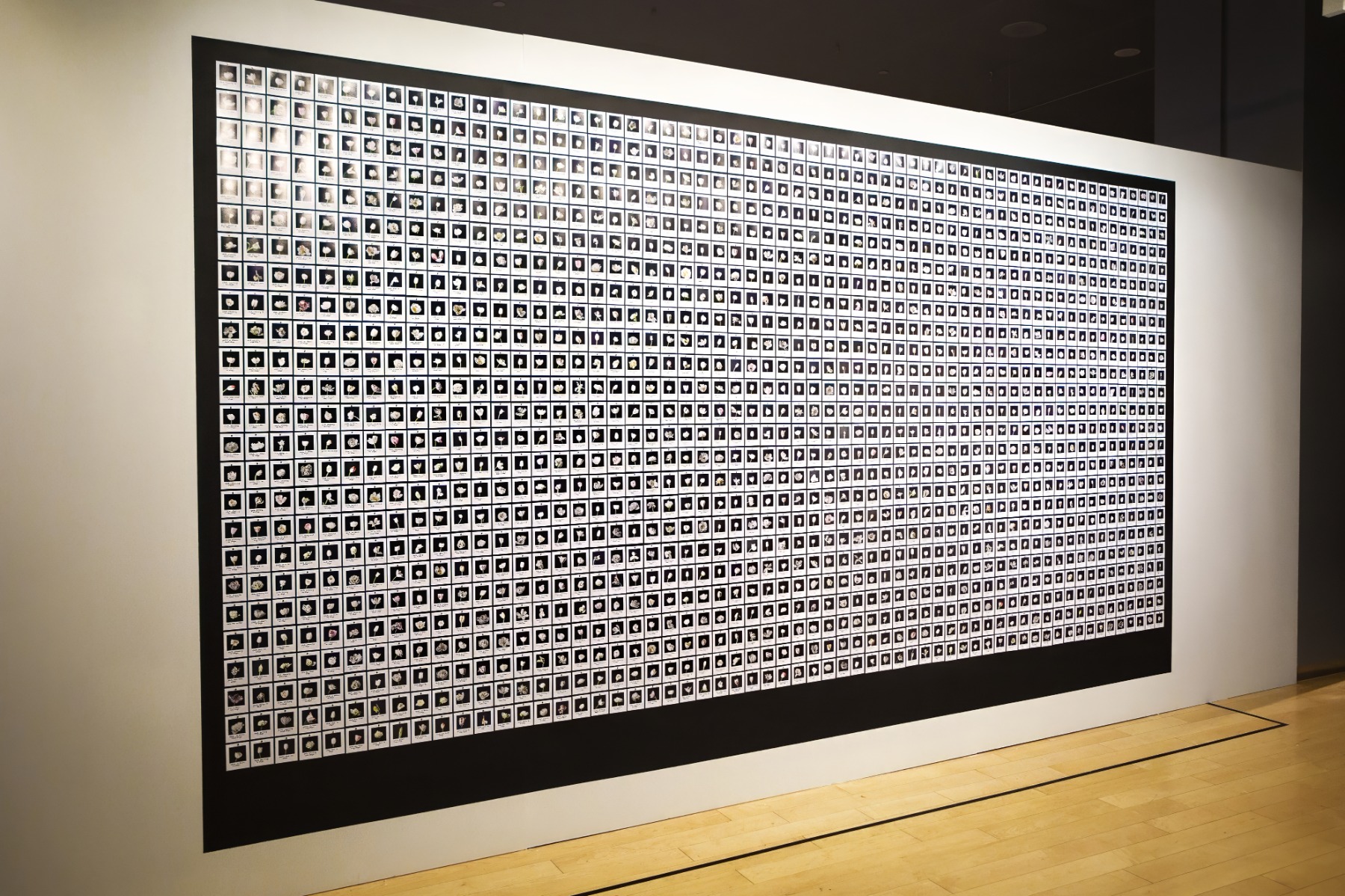

I did all this work of creating a dataset to create another work. Initially, I only intended to make the works of Mosaic Virus, which are moving images – AI-generated works. But as I was making the dataset, I realised that I really wanted to bring to the surface the time, labour, effort, and understanding that went into making the dataset. Because back in 2018, people weren’t talking about datasets the way they’re talking about them now – understanding bias, understanding the issues around intellectual property, ownership, and all these things. I wanted to display the dataset as a piece of art. So I took the photographs, created them, and hand-wrote the labels underneath them to really emphasise the human element that sits behind so many machine learning processes. It’s always the case that it isn’t just the machine making the decisions. Always somewhere within the chain, there will be someone deciding whether something is either red or orange.

Only a fragment of Myriad is shown in the exhibition as the work itself takes up about 50m2. You have a very different experience when information is made physical and you understand all these things – the effort and labour – when you walk past it and look at it, rather than just scrolling through it on a screen. The installation also deliberately emphasises the balance between perfection and imperfection that sits at the heart of creating datasets. In the installation, the photos are held on the wall by magnets, so even though it looks like a perfect grid from afar, when you get closer you can see the very imperfect nature of it. That, again, was a deliberate decision. Rather than printing them on a perfect sheet of paper and installing it, each photo has been put on separately – and it takes a long time to install it. The whole thing is intentionally laborious.

The work is also making connections to other artworks that deal with categorisation and repetition as well as to the lineage of floral data sets that sit in machine learning. One of the earliest datasets from the 1930s is called the IRIS dataset, as named by Ronald Fisher. IRIS is included in a very commonly used machine-learning software package, so there are thousands of little IRIS datasets on every single computer that is run in machine-learning modules.

But the tulip itself also has a history, and you’re working with that as well. Could you expand on the symbol of the tulip?

I feel that the piece is, in a way, quite feminine – it’s quite a pretty piece, delicate and beautiful. I’m interested in taking objects that are seen as feminine, like flowers or love letters, and really telescoping through their history. Cut flowers are sometimes seen in art as being quite kitsch. But if you look at how cut flowers are produced, a whole history of globalisation and commerce and climate change unfolds. It all sits behind this thing that you just pick up in the supermarket for a couple of euros. I became particularly interested in tulips and their history because one of the most well-known things about them is this moment in history called “tulip mania”. During this time, the price of a tulip bulb went for the same price as an Amsterdam townhouse...and then a couple of years later, it fell to the price of an onion. It’s seen as being one of the first recorded instances of a speculative bubble. I think there’s something really interesting in collapsing these systems around money and value with the natural world, and through those moments, seeing how ridiculous these things are.

In Mosaic Virus, you connect tulip mania to another more recent mania – the one involving cryptocurrency. What kind of parallels did you find?

I’m not the first person to make the connection between tulip mania and crypto. People have been connecting them since around 2016. But for me, there are obvious connections between how they behave on a chart and on a graph, where you can see the value going up and then quickly collapsing. Another instance that goes beyond that is how many people speculating on tulips and cryptocurrency (I was particularly looking at Bitcoin when this work was being made in 2018) didn’t really understand what it was or how it worked or what blockchain was. There was this whole movement, an example of which is the Long Island ICT Corporation, which changed its name to the Long Island Blockchain Corporation. Its share price rose ridiculously – around 3,000% – when it did that because people just didn’t understand how Bitcoin worked. They were just like, oh, this is a thing that will make money. And the same thing happened with tulips – people didn’t understand what was happening. The work Mosaic Virus is called after the virus that causes stripes on the petals of tulips. Tulips with stripey petals were the most valuable. During the mania, they were the ones that commanded the highest price because people didn’t understand how those stripes happened. It turned out it was an insect laying its eggs in the bowl that caused this mutation, so you could have a tulip that would be white one year and then have stripes the next. And people didn’t understand that, so they were just trying to get these stripey tulips in many weird ways. So, there’s a similarity in how people did not know how the thing that’s causing the wealth really works. The other moment of speculation in the piece is the deliberate choice of using artificial intelligence. That’s because while I was making it, there was this huge boom in deep learning and the effects of it. There was this big push of companies and governments pumping loads and loads of money into the AI industry, when a decade earlier, it was seen as being almost an academic backwater. So, there are other aspects of boom and bust that are in the work beyond the mere financial.

This tulip virus, the mosaic virus, is a disease. I read that it became even threatening to other tulips because it spread so rapidly. Do you see cryptocurrency as a virus? Do you see it as a sort of sickness of us as a society – making such a fuss about it without even understanding the mechanics behind it – or, do you rather see it as the market always trying to come up with something new – and inadvertently causing a collapse of the market?

I think in and of itself, it isn’t a virus. I can see our behaviour as being virus-like – this obsession being contagious. As you can see with NFTs, it is shaping how people are forming themselves as digital artists and it’s spreading over the digital space. But I’m not sure about it.

I guess we’ll see how it evolves. Do you think that referencing nature and finding parallels in natural processes helps us make better predictions, for example, about what might happen with artificial intelligence...or if we connect it to us and make it more natural and more relatable?

I am really interested in the parallel between natural history and how machine learning is being enacted now. If you look at how the world has been shaped and described by natural history, some of the problems that have come out of that – the way that we try to impose our understanding of the world onto nature, what gets left out, who decides what gets included, who collects the information, where that information is stored, how it’s observed, issues around spectacle, etc. –have been very interestingly unpacked by historians of science and are becoming relevant in the debates about machine learning. Particularly in relation to nature, problems about the relation between science and nature – like the erasure of indigenous knowledge and the centring around Western scientific observation – become vivid. It has been very well documented and explored in a really interesting way. Also, all the problems with subjectivity and objectivity are there in this field of history of science. I think that my work is part of that lineage – not only describing the world but also indicating the problems with describing that world. The way that I came to machine learning was through working with academic researchers. And that’s where I see this work sitting – in understanding nature in a scientific context and through the lineage of the history of science.

Categorisation is a process that underlies many natural sciences, modern biology in particular, and that’s just what you did in creating Myriad. However, when categorising, there is always a problem with subjectivity. How did you choose the three criteria for Myriad – colour, striping, and state?

I chose them because, ultimately, I wanted to be able to control these qualities in the video work. As I said, a machine doesn’t automatically understand any characteristics unless you tell it. I wanted the result to be reflective of what I saw versus just putting them through an algorithm and letting the machine decide. I wanted it to be a very authored work.

This leads to a more difficult issue, namely, that any dataset is authored. You mentioned an example in the talk you gave – the picture of a woman created on the basis of a certain dataset was just so stereotypical. That’s something that has been a worry in recent debates – all the biases of artificial intelligence that we are actually implementing in technology. You decided to control the dataset very deliberately. Do you see it as a weakness or a strength of artificial intelligence – the fact that you can create it in the way you want to?

I don’t see it as a weakness or a strength. I see it as just being neutral. That’s something that you decide to work with or ignore. When you choose to work with oil paints, you’re choosing to work with something that will dry very slowly. That’s just the nature of the thing. But I think you have to be conscious of that when you choose to work with it. You have to understand that you’re either deliberately working against it by making your own data set, labelling it, and really leaning into that part of the process, or, as other artists often do, use off-the-shelf data sets and off-the-shelf algorithms. I think both of those are equally valid approaches, but you need to be conscious of how it works and what the process is doing. I want to explore what’s in the machine-learning process and what’s not in there and then expose that.

Constructing datasets could also mean programming society. It opens up a big opportunity to deliberately change outdated narratives. For example, if we’re struggling with unequal women’s rights, we can change the idea of women by working with the datasets. On the other hand, it’s also very dangerous as, for example, propaganda can be distributed and created more easily. I find that it’s very scary how well you can manipulate common opinion and discourse through it.

Yes, these large data sets are reflecting what people think already, so in many ways, it’s not creating these sexy images of women from nothing. It’s creating these sexy images of women because it’s been told that a woman looks a certain way, and the reason why it’s told that is because there is this cultural assumption. So, in a way, what technology is doing is just holding up a mirror to society and showing it in a warped, contorted way.

Do you think we can speak of different characters or personalities of artificial intelligence modules based on different datasets? As in, you’ve put your subjective view on tulips and natural history into this dataset, so can we now say the the model has a certain character?

I don’t know if you can speak of character, because I’m always wary of anthropomorphising artificial intelligence. But I do think that there’s a tone that my models have, a style or something similar that sits inside of them. I see it as my deliberate nature. But I don’t think that they are characters; they’re not actors and agents in and of themselves.

When talking about Myriad, you touched upon how much of your time, effort, and human labour was put into it. For me, it made the artificial and inhuman technological processes way more relatable. It made data more human in general. I find the concept of data very inhuman at points because it tends to homogenise people when it isn’t necessary, and it tends to create groups where that isn’t actually the case. But your work and effort made it relatable and human. Was this an intentional attempt to relate technological and human processes?

Yes, it was to make it deeply personal. It is a very personal thing to create a world because the act of creating it consists of intently looking at these objects again and again and again. It’s like you have an intimate relationship with the data that you’re using, which is something that you don’t have when you’re just downloading off-the-shelf datasets. It’s almost like giving grace through the act of paying attention and through this relationship that you have with data.

Do you think we should treat technology as part of our environment now?

It’s weird. I think I mentioned it a little bit in the talk that I gave at the library – technology just is; it exists. Like a garden. We could ask: is it natural or unnatural? Because it consists of living green organic plants, but at the same time, it’s been designed and controlled by a person, a human. You would never get a garden in the wilderness. And it’s the same for technology, in a way, because it’s not imaginary – it exists in the real world; it exists. It’s created from rare earth metals and it’s something that is in our world. And we engage with and interact with it. So, I think of it as being a real physical thing.

It made me think how it actually has to do with the word “intelligence”. I think that’s what makes AI not a thing but something that might be even more human than nature is – more human than plants are, for example, which we tend to treat as just objects.

A lot of the people who are now artificial intelligence researchers trained as neuroscientists, so there’s this really strong link between trying to replicate human intelligence into these systems or trying to design these systems to mimic human intelligence when, of course, there are other forms of intelligence that exist in the world. Plant intelligence, octopus intelligence – they’re so clever but so different from how humans behave. Again, it comes back to categorisation and labelling and what are you trying to copy or mimic.

Do you think it’s false or just a linguistic game that makes us imagine it as being more human than other things?

I think it’s just how we are. From a really young age, babies will recognise things that look like a human face. I think it’s just hardwired in us to try and recognise ourselves in other things.

Do you think that’s a premise we should work upon? Or do you find that we are failing to notice the differences in how humans and AI work?

I think what we probably need to look at is valuing the other forms of intelligence – seeing value in other systems and ways of being in the world and understanding it, particularly at a time of climate crisis.