On the ecosystematic perspective in the arts

The ECODATA exhibition held at the National Library of Latvia is the central axis of the international RIXC Art Science Festival

In the beginning there were sounds: leaves rustling, sea waves coming and going, a man saying something firmly but gently, a woman singing a melancholy almost cry-like song, children laughing and running. As I walked through the doors that lead into the ECODATA exhibition held at the National Library of Latvia, I felt engulfed by the soundscape. Then I became conscious of the white walls, the bright lights, and the abundance of screens – for a moment I lost my bearings. Not in an uncomfortable way but in a way one may feel on a sunny summer afternoon in a forest: so much to attend to, to breathe, to observe, to feel a part of.

The ECODATA exhibition is the backbone of the RIXC Art Science Festival. The festival aims to investigate new media, technologies and techno-scientific methods (registering, collecting and interpreting data) in the arts. This is done to understand the role and significance of the interaction between biological, social and techno-scientific systems, living and digital data, and artistic and scientific approaches for the perception and awareness of the ecological. In other words, the festival’s aim is to bridge the gap between the technological and ecological as well as to incorporate technological issues into ecological art. ECODATA features twenty works of art by internationally acknowledged artists working in the field of media art, science and ecology.

Ursula Biemann. Acoustic Ocean. Video Still. 2018.

Gravitating to the most prominent source of sound, I found myself in front of Ursula Biemann’s Acoustic Ocean. On screen, a woman in a bright orange aquanaut suit installs sound equipment (hydrophones and parabolic microphones) by the waterfront. Her hair is braided with a red ribbon, she has a fur around her neck, her fingers are adorned with rings: she appears to be prepared for an ancient ritual, if not for the wetsuit. And in some ways, she is, because her goal is to connect and hear the living beings in the depths of the ocean by detecting the sounds they produce. Such an image of science as ritualistic practice makes viewers rethink the position of scientists in relation to nature. Pagan practice regards nature as the strongest untamable force, a force that needs to be respected. Scientific practice regards nature as something that can be observed and explained (and sometimes even tamed). Biemann invites us to look at the ocean as an inexplicable and infinitely mysterious force, to feel small, to feel clueless for a moment. She reminds us that there is still a lot we don’t know about the ocean, and she reminds us that there are things we do know about the ocean. And yet, the best we can do is respect it and ask it permission to explore it, in the manner of a ritual.

Marcus Maeder. Perimeter Pfynwald. 2018-2020.

Perimeter Pfynwald by Marcus Maeder takes us into a different soundscape – the Pfynwald forest in Switzerland. There, we get to experience the effects of climate change through spatial and temporal compression via acoustic time-lapse and the spatial arrangement of speakers. The changes in the fauna, the drying up of the streams, the river filling up with melting ice – all this we can hear. Standing in this imaginary Pfynwald, I thought that there must be many other forests where one could do such a project. The irony lies in the fact that, in our pandemic-induced confinement, we’re looking for connection with remote places through technology. Perhaps, this is a chance for us to look around at the places close to us and see whether there is anything we can do for them?

Susana Soares. Urpflanze. 2013. Print and digital design.

Nature – so close by, so accepting and resilient – is in need of help at this moment. We know it too well already; we are aware of the urgency. Now feels like a time to look for answers. In Urpflanze, Susana Soares ruminates on whether we can redesign plants to be more adaptable to the weather conditions arising due to climate change. The artwork is a series of prints of imagined plants accompanied by texts explaining the morphological changes they have undergone in order to adapt to the new climate. Soares introduces us to current research in the field of plant morphology, such as putting together the genetic blueprint that controls plant structure and shape. This is a potential first step in designing plants that are more adaptable to the planet’s changing climate.

Francois Knoetze. Cape Mongo. Video. 2013-2015.

The origins of climate change are multiple and date back to the industrial revolution. Unwinding this web of history sometimes feels like rediscovering a myth we’ve created collectively. It is not easy, but it is important to understand how we got to where we’re at. Francois Knoetze’s Cape Mongo – with mongo being an object thrown away and then recovered – takes us through filmed stories of six characters in Cape Town, South Africa. Each protagonist’s costume is made from plastic waste: wraps, caps, scraps. The characters are mythical “trash creatures” that have emerged from fast consumer culture. The myths, legends and pagan attention to the natural so present in Eastern European cultures make points of connection with a place as remote as South Africa, reaffirming the commonality of humanity, the sense of mission that we all need to have together. Knoetze’s work reminds us that our mission now is to deal with the “trash creatures” our ancestors gave birth to and that we carry on giving birth to. Cape Mongo is a series of six short films in which the creatures come back to their places of origin: shopping malls, suburban districts, schools, industrial centres. Watching them, we start to comprehend how history has taken the course it has, with systemic inequality and alienation at its heart, leading to the slow destruction of the planet we’ve been given. We need to look at Cape Mongo as if in a mirror to understand that some things of the past need to remain there, otherwise the “trash creatures” will come to face us. In fact, they are confronting us already. But, much like the gallery screen that can be easily turned off, we decide to remain with our eyes closed.

Maayke Schurer. Papers Ocean. Video Still. 2014.

Yet, even if we do close our eyes, nothing disappears, and this is something we’re all too aware of from childhood hide-and-seek games. Right now we’re hiding, and the consequences of our actions towards nature are seeking revenge. It’s a spell-like quality we cannot counteract, and the magic realist videos of Maayke Schurer, titled Papers Ocean, remind us of this. Plastic bags, pieces of synthetic fabric and bottles choreograph a captivating dance in the ocean and in the air. The beauty of these shots is terrifying. How can something so wrong be so beautiful? And, similarly, how can something we do every day – consuming, throwing away – feel so normal, yet be so wrong?

The works of art do not try to give us answers to these questions, they do not try to moralise. They just make us see what we don’t want to see. The tension between the harmonious beauty of natural environments we are immersed in at the ECODATA exhibition and the threatening consequences that every now and then slip into the images or short pieces of writing is palpable. This tension does not seek to be resolved immediately. It is a gradual process that requires us, on different sides of the planet, to unite for the common goal of saving the planet.

Rasa Šmite and Raitis Šmits. Atmospheric Forest. 2020. Immersive installation

The Ecodata–Ecomedia–Ecoaesthetics festival partner replicates such multinational collaboration in miniature. Funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), the project has both a theoretical and a practical aspect. Yvonne Volkart (CH) leads the theoretical part and analyses a number of international ecomedia projects. In particular, she looks at aesthetic idioms in order to develop a techno-eco-aesthetics of relationality and care that goes beyond the technological. As part of the practical aspect, the artists-researchers Marcus Maeder (CH), Rasa Šmite (LV) and Aline Veillat (FR/CH) develop aesthetic projects relative to the Pfynwald forest. This alpine forest in Valais, a region in southwestern Switzerland, is a unique site for observing climate change in forest ecosystems and has been under close surveillance by natural scientists for more than twenty-five years. The intertwining of the theoretical and practical parts of the project is an attempt to create an aesthetics of theorypractice or practicetheory, a multifaceted artefactual poetics of the more-than-human.

ECODATA is curated by Yvonne Volkart (CH), Rasa Šmite and Raitis Šmits (LV). The cohort of artists is multinational, with participants from Switzerland (Ursula Biemann, Sarah Burger, Marcus Maeder), South Africa (Francois Knoetze), the Netherlands / Denmark (Diana Scherer), Canada (Maayke Schurer, Elaine Whittaker), the United Kingdom (Semiconductor), Portugal (Susana Soares), Latvia (Rasa Šmite and Raitis Šmits), the United States / Denmark (Tamiko Thiel and /P), Finland (Leena and Oula A. Valkeapää) and Estonia / Spain (Varvara & Mar). The media include video, augmented reality installation, textile collage, plantroot weaving, carbon drawings and prints.

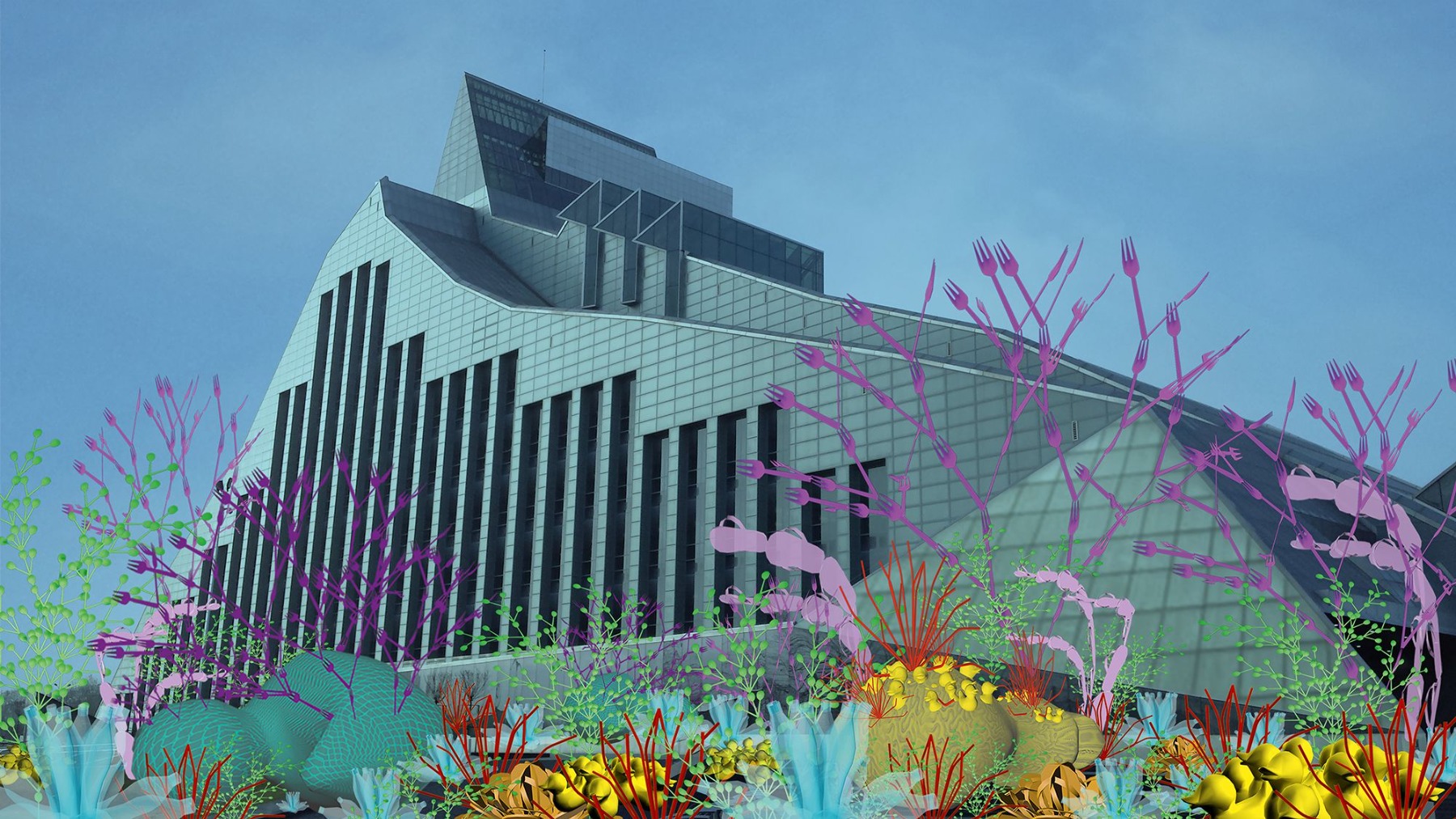

Unexpected Growth, augmented reality installation, Tamiko Thiel and /p, 2018. Visualization in the National Library of Latvia.

ECODATA is on show at the National Library of Latvia until November 18, 2020, so you still have a chance to visit.

* Most of all, Aliaksandra Tucha likes to play. She plays with words on paper and screen, with actors on stage and behind the lens, with paints and cameras – in short, with anything or anyone she encounters on her way. Originally from Belarus, Tucha is studying visual arts (film concentration) at Yale College. You can send a letter to her at aliaksandra.tucha@gmail.com.