On Hopeful Fragility

An interview with art duo Pakui Hardware who will represent Lithuania at the 60th Venice Biennale

Contemporary art duo Pakui Hardware (Neringa Černiauskaitė and Ugnius Gelguda) and the modernist painter Marija Teresė Rožanskaitė (1933-2007) have been chosen to represent Lithuania at the 60th Venice Biennale in 2024. The Lithuanian Pavilion will be organised by the Lithuanian National Museum of Art and will be curated by Valentinas Klimašauskas and João Laia. Pakui Hardware is known in terms of their unique visual language that integrates both synthetic and organic materials in hybrid spatial installations. When thinking about their work, keywords such as material sensitivity, corporeality and post-humanist approach come to mind. Body has been one central theme to their practice since the inception of Pakui Hardware. For example, one can notice an interest in different capabilities and biological processes of a human body, or in the relationship between the human body and contemporary technology. Pakui Hardware investigates how current economic and social conditions affect human bodies, but also humanity and nature in a wider scale. Connecting the spheres of human, non-human and technological, these sculptures that carry the qualities of a beautiful technological utopia are somewhat like creatures of the future that show us the direction where a society based on a global capitalism may develop in the coming years. We spoke with Neringa Černiauskaitė and Ugnius Gelguda about their creative work, the themes and the design of the Venice Pavilion exhibition, and the artists’ relationship with Rožanskaitė’s work.

Pakui Hardware – Neringa Černiauskaitė and Ugnius Gelguda, 2020. Photo by: Arūnas Baltėnas. Courtesy of Pakui Hardware

How did the idea of a joint exhibition, which will also include works by the modernist painter Marija Teresė Rožanskaitė (1933-2007), came to life?

NC: It was an interesting combination of how “stars connected” because back then we were preparing a very large solo show in Museum of Applied Arts and Design (Lithuania). We invited Valentinas Klimašauskas to curate it. During the same meeting, he invited us to apply for the Venice Biennial, with a slightly different project at the beginning. It was an interesting synergy. And thus, the show in Vilnius became like a prelude for the Venice project.

Overall, we have been interested in Rožanskaitė’s work since 2018, when we started working more with the topic of contemporary medicine, and the ways it transforms bodies. On this theme, we did the first show in London at Tenderpixel which was dealing with metabolism and where we worked with glass to create “stomach’s sculptures” – which were a reference to bariatric surgeries where the stomachs are sculpted (to reduce the amount of food that comes into the body). For us it was a way to speak about metabolism in society where there were often these issues raised about boosting your metabolism etc. It was also a metaphor to talk about metabolism as something where the body is in a relationship with different materials, systems, and environment as such.

This was about the time when we discovered Rožanskaitė’s medical pieces. We were really fascinated how contemporary they looked. Even if they had some references to 1970s and 1980s aesthetics, then in these works she still managed to combine the fragmentation of bodies, medicine, body, and different technologies, and all the abstraction incredibly well.

In 2020 we did a series of installations that is a trilogy, which is dealing with telemedicine and robotic surgery, and different medical procedures that were done through technological mediation. One show was called “Virtual Care” which was shown at BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, U.K. It was installed completely through Zoom in 2020, and then opened in 2021. It was about different ways in which human bodies don’t touch each other; where the patient does not meet the doctor: the medical procedures were either done or mediated by technology. This is when the paintings of surgical operations by Rožanskaitė really inspired the fragmentation and abstraction of the bodies into different states – like a mental state or a spiritual state. In this exhibition, virtuality, technological care, and the merge between technology and the bodies became quite central theme.

Another exhibition was at carlier | gebauer gallery in Berlin, and it was called “Absent Touch”. And the last one was titled “The Host” which was shown at Eastcontemporary, Milan. When we were working on these shows, especially in the beginning, before COVID, it was very kind of niche topic – telemedicine, robotic surgery, etc. But with COVID it became mayor way to reach your doctors, everything was mediated, and “technological care” became a mayor topic in an eery way – life caught up with art.

UG: And I think it’s very important that there are not so many examples – artists who work in this context and with these topics, like medicine, in general. So, for us the fact that she is Lithuanian, and not too well known – not even in Lithuania – was a really good opportunity to bring her again to the light.

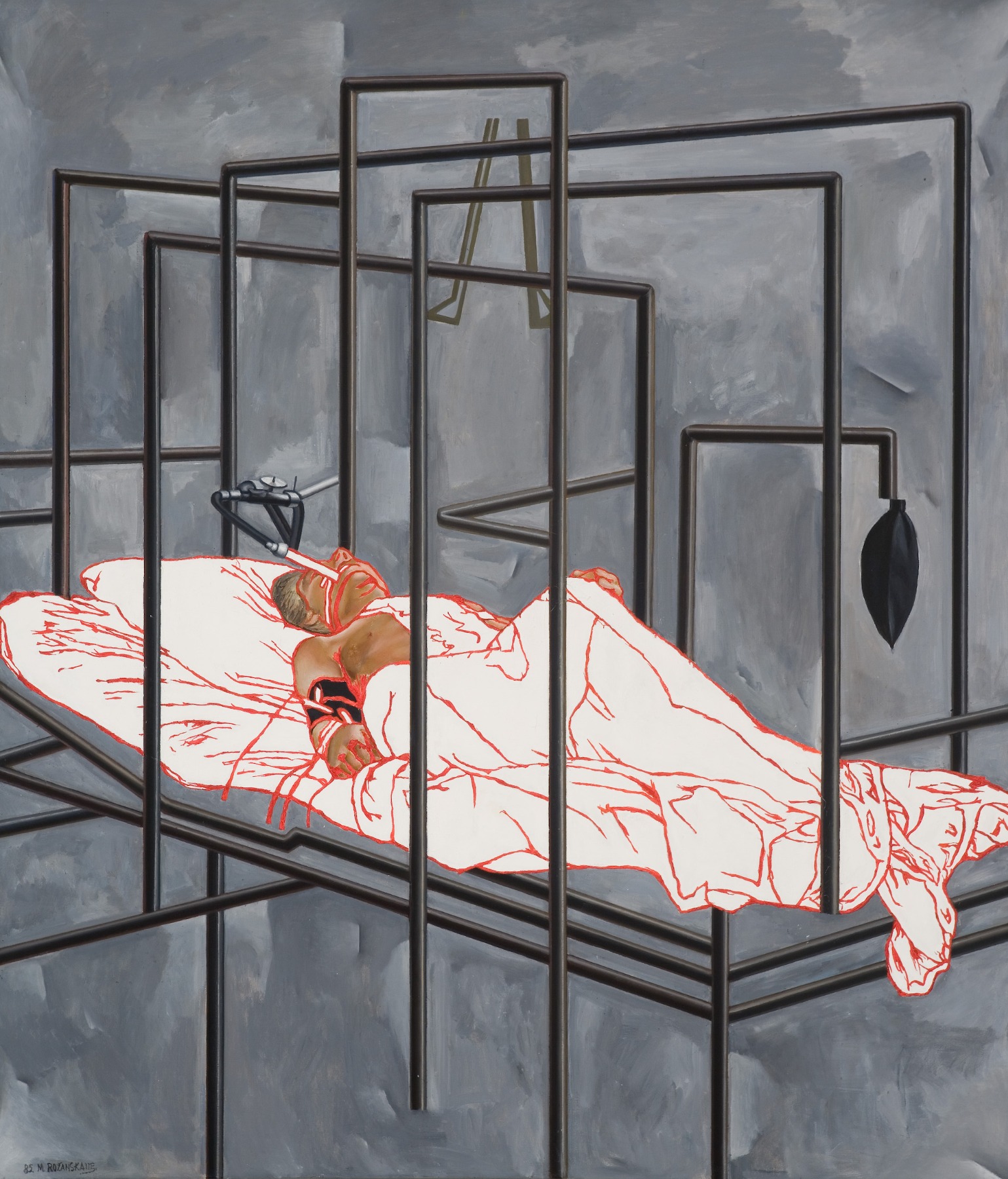

Marija Teresė Rožanskaitė, Disease, 1985. Oil on canvas, 150 × 130 cm. Photo by: Antanas Lukšėnas. Courtesy of the Lithuanian National Museum of Art

In the case of Rožanskaitė, it has been pointed out that she was rather an exceptional artist in Lithuanian art history. It can be argued that Rožanskaitė defied the rules of the art world at the time both with her unconventional self-presentation and with her new visual language. What do you find especially fascinating about Rožanskaitė’s work?

UG: Especially her works from 1970s and 1980s, and her unusual way of showing human body in fragmentation. It’s maybe a bit similar to Alina Szapocznikow. She already worked with that kind of body fragmentation in the 1970s. It is kind of similar approach, but in different medium.

NC: As we were researching this field, it was not a regular case when you find a historical artist working on the theme of medicine. Also, we were kind of astonished how contemporary these works were, even though they were done in the seventies.

In her works, human bodies are almost devoured by technology, by the instruments, by the tubes that enter them, and the fabrics that are covering them. You can see how the technology “swallows” the body: it’s like erasing the individual. Hence, the anonymity of the subjects that are shown is very important: they are rendered to be anonymous by that technology. On the other hand, in her work there also emerges the topic of the invasiveness of medicine: how it exposes the internal parts of the bodies. It is something you cannot hide from. It comes also from the time she was working – the Soviet regime. This context of monitoring of your everyday life and even your thoughts. In her time, it was very much about building huge hospital complexes too. So, the medicalization of bodies became even more anonymous and de-individualized.

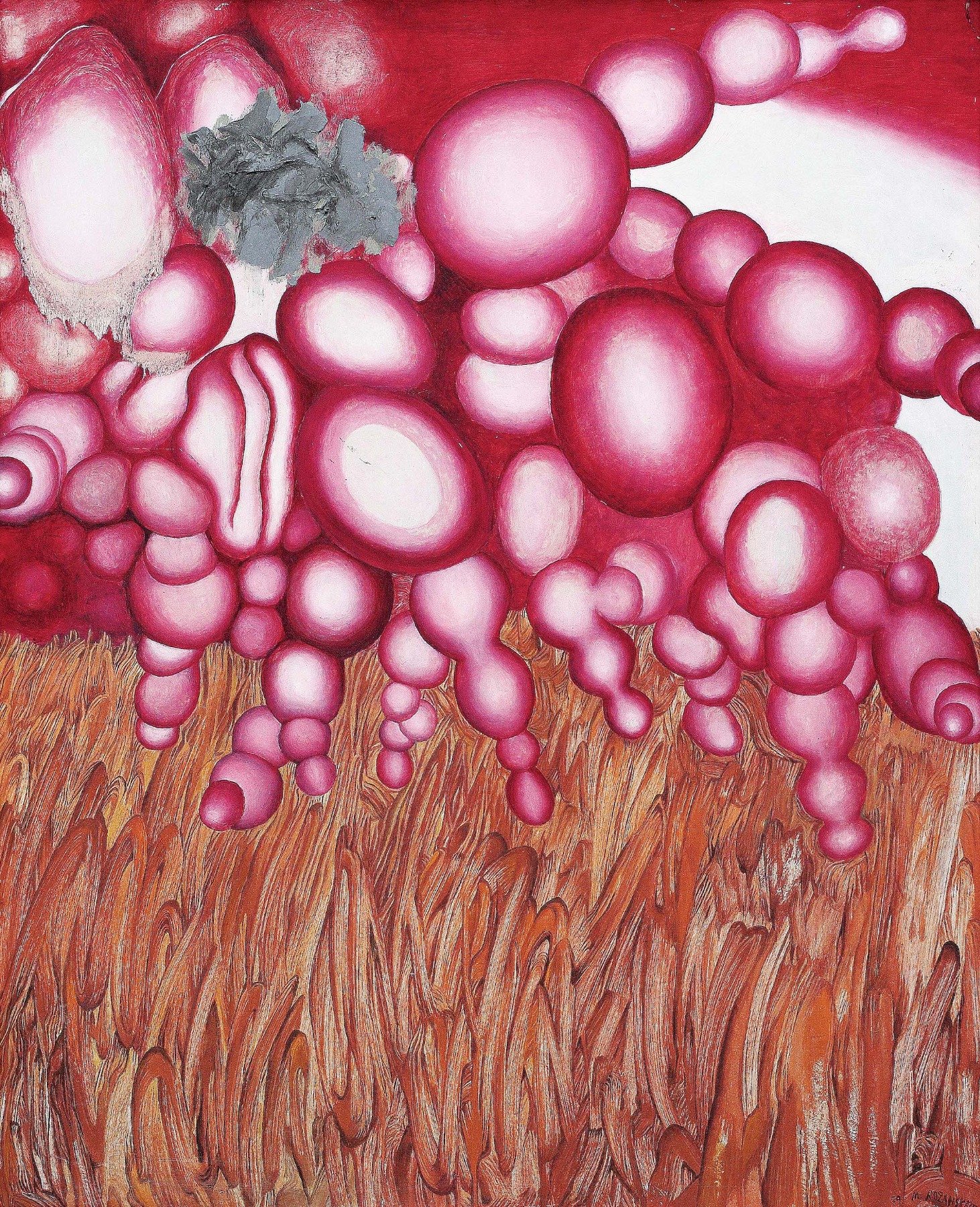

Marija Teresė Rožanskaitė, Cosmic Composition, 1979. Oil on cardboard, 122 × 105 cm. Photo: Vidmantas Ilčiukas. Courtesy of the artist’s family

You mentioned that the exhibition “Inflammation” at Museum of Applied Arts and Design became like a prelude for the Venice project. So, does this mean that the new exhibition will be mainly based on this? What will be the relationship between your new works and your earlier works?

NC: In Venice we are mainly showing the selection of sculptures that were shown in Vilnius, with some modifications. As the last show in museum also spoke about “inflammation”, we used all kinds of different mediums and techniques to create a certain “feverish state”, in which the viewer enters. But in Venice the whole architectural set up will be very different, because it will be presented in a church. It is called Sant'Antonin church, which has not been open for worshipers or visitors for about ten years. It is a very different setting in which we have to build architecture within architecture. Currently we are working on this environment forming with an architectural duo – Isora x Lozuraityte Studio for Architecture – and with the light artist Eugenijus Sabaliauskas. This whole atmosphere is going to be completely remodelled according to the space and scenario we have planned for the visitor.

Pakui Hardware, Inflammation, 2023. Photo: Ugnius Gelguda. Courtesy of the artists, Lithuanian National Museum of Art and Carlier|Gebauer (Berlin/Madrid)

But how do you feel: how is the chosen physical space influencing the project? And how does your collaboration with the architectural duo look like? I have understood that this is not the first time you collaborate with architects on your project.

UG: We started working with these architects when we were making an exhibition “Vanilla Eyes” at MUMOK in Vienna, in 2016. These were like the first steps of our collaboration. And it became a deep dialogue that was manifested in several other exhibitions, in MdbK museum in Leipzig for example, and of course in Vilnius. In Venice they are an important part of the team again. On this project they will work more autonomously as landscape architects or designers. It’s a bit different moment in their practice – quite a solo vision let’s say.

NC: In Venice they are building what one of the curators, Valentinas Klimašauskas, beautifully called “a station of hope”. So, it will look a bit like some kind of outdoor pavilion, or outdoor space, but very abstracted. I call it “the motherboard” because it’s kind of a megastructure on which everything will be mounted, which will emanate light, and which will become a source for energy too. It will contain all sculptures, the landscape, the light. Also, Rožanskaitė’s works will be integrated into this landscape, so they are not something that will be presented separately. Her works will be shown in specific vitrines that we suggested as an idea and that the architects have designed. These vitrines refer to these outdoor infrastructures where you sometimes see advertisements and posters in a public space. So, these are references to urban landscape too.

And the light designer will create a kinetic light atmosphere. In this case, the light design also refers to how lasers are used in medicine; how they are used for healing, and monitoring. At the same time, they are extremely dangerous if you misuse them. The room, in which the installation will be, will also become a body that is “scanned”.

In Venice, unlike in Vilnius, there will be no kinetic movement of the sculptures themselves. Vilnius was specifically done for that space that has columns, and where sculptures appear and disappear behind each column, so it had this “wandering around” landscape feeling to it. But the church is much smaller, and its open, so it does not have these moments where sculptures could “hide” – and they look in a very different manner. This feeling of movement of the space in relation to the bodies of the viewers will be done through other means, like light and sound, which will be a new element.

The exhibition design also refers to Rožanskaitė’s work “Disease” (1985) where a patient is lying in the bed in this abstract grey background. And there are these columns, or a structure that surrounds it. It is quite naked as a structure: it supports the body, but it also controls it or frames it.

Pakui Hardware, Inflammation, 2023. Photo: Ugnius Gelguda. Courtesy of the artists, Lithuanian National Museum of Art and Carlier|Gebauer (Berlin/Madrid)

I guess it is quite interesting challenge to create an exhibition in the physical space of a church. Do you have any thoughts about this context?

UG: This particular church – Sant'Antonin – is not very typical because it was closed for many years. It has this atmosphere that is really hidden from the visitor. It feels more of a secret space, than sacred. It’s very different from what you think when you think about a church.

NC: Yeah, it has this sense of derelict to it. And in that sense, it is kind of post-cultural. It has all the elements of a church, but it kind of feels almost post-human environment because it has a sense of dereliction. And it’s also quite meditative.

When speaking about the idea of inflammation that comes through subjugating nature, and all the species, the church also has a very interesting backstory. There is a story that takes place in the 18th century where they brought an elephant to Venice carnival, to be part of the entertainment. But the elephant ran away from the carnival, and everyone were chasing it, until it broke into that church. Allegedly, it was shot through a hole they opened in the church, so it was killed in the church. This story is very charged in lessons: it’s about nature that is subjugated and that tries to break free, and then is terminated.

Pakui Hardware, Inflammation, 2023. Photo: Ugnius Gelguda. Courtesy of the artists, Lithuanian National Museum of Art and Carlier|Gebauer (Berlin/Madrid)

Could you also introduce in more detail the themes and motifs you are dealing with in your upcoming exhibition? I have understood that one of the central keywords of the exhibition is “inflammation”. What does it mean in this context and where does it come from?

NC: Initially it came from our interest in contemporary medicine and how it transforms the bodies. We found a book called Inflamed: Deep Medicine and the Anatomy of Injustice. In that book, the authors speak about inflammation as a natural and ancient “technology” of the human body to deal with the diseases and viruses, adversities that happen with the body. But when it becomes a chronic inflammation because of the constant exposure to unhealthy conditions, then it becomes a problem that is out of control, and it becomes destructive. So, instead of healing, it becomes a destructive technology. The authors Rupa Marya and Raj Patel describe the source of these chronic and systemic inflammations that happen – not only with human bodies but also with the planetary body – as colonial capitalism. It extracts resources from every corner of the world, and this way creates histories of oppressions, and those histories travel in human bodies from generation to generation, ending up in forms of inflammation. So, it’s a powerful way of connecting history, biology, and ecology in this poetic manner. This is an important position for us.

In our previous works one could find a criticism of Western cosmology in our works, which is about separation of the mind from the body, human from nature, white male from other beings etc. This separation allows you to dominate over what you separate yourself from. For us this kind of Cartesian dualism is problematic. It’s also a separation that is prevailing in Western medicine: healing only particular organs, without thinking about the body, entangled into a web of relations. In our previous practices we always talked about embodied subjects, and the importance of bodies in a relationship to the environment – to show the dependency on each other. So, in this case, we too want to critique this Western cosmology of fragmentation, through showing the fragments of human nervous systems in these sculptures, but also connecting them to the planetary body by the landscape that is formed in this installation.

Pakui Hardware, Inflammation, 2023. Photo: Ugnius Gelguda. Courtesy of the artists, Lithuanian National Museum of Art and Carlier|Gebauer (Berlin/Madrid)

As mentioned in the press release, the exhibition will investigate the various fevers currently shaking humanity and the world. According to the authors of the book you mentioned, inflammation is a healthy bodily response to unhealthy conditions. Therefore, rather than ‘cure’ individual sick organs, we should cure the very systems – economic or social – that cause chronic diseases to be transmitted from generation to generation. What do you think: how could we realize this idea in a world where nations are becoming increasingly concerned about their own fate, and where we don’t have enough powerful global institutions that could take on this planetary mission?

NC: I think what we are trying to emphasize with this project, is the importance to question the building up of artificial “immune systems”, and unlearning specific kind of thinking, which is oriented towards domination and extraction. We want to bring forward the idea of moving towards more interconnected understanding of things, and seeing oneself, other nations, and other species as interconnected and dependent on each other. We should find ways to learn dependency and the consequences of actions that we make on daily basis.

Like one of the authors of the book – Rupa Marya – said in one of her interviews: we cannot think of ecology and capitalism together, they’re just mutually exclusive. There cannot be a healthy world if you have capitalism. It’s just impossible, it is a paradox. Now we are almost in this melancholic mode of accepting the fate of humanity and extinction scenarios. But we should have courage to dream in more daring and poetic ways, and be able to imagine other ways of being, let’s say.

Pakui Hardware, Inflammation, 2023. Photo: Ugnius Gelguda. Courtesy of the artists, Lithuanian National Museum of Art and Carlier|Gebauer (Berlin/Madrid)

You are known for a practice that utilizes both organic and synthetic materials in installations and sculptures. Will there be any new and previously untouched materials used in your exhibition in Venice?

UG: I think for us the newest or the latest material is aluminium. We tried it for first time last year and we used it also in Vilnius show. It nicely reacts to and creates a dialogue with the lights. It’s unusual for us, because it’s not easily mouldable, it is a very solid material. With the aluminium we have created a human nervous system which is like a spatial drawing. It is very abstract, and translucent in the space.

NC: Yeah, it’s a metal – so it’s something quite rigid. But it’s also very fragile, and very light. These “spatial drawings” are quite particular when you see them because they seem sculptural, but when you see them from the side, they are completely flat. They play with dimensions of a drawing and of a sculpture. These spatial drawings will be combined with glass – which became our signature material at some point. The installation has a stainless-steel aesthetic to it, and structures referring to medicine and to Rožanskaitė. As Valentinas Klimašauskas pointed out, it’s kind of a techno-organism that will be built in that space.

Pakui Hardware, Inflammation, 2023. Photo: Ugnius Gelguda. Courtesy of the artists, Lithuanian National Museum of Art and Carlier|Gebauer (Berlin/Madrid)

How does the project relate to the general theme of the Venice Biennale? How do you interpret the proposed theme of the Biennale – “Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere” – for yourself?

NC: In our case, we emphasize the idea of what is foreign in a more biological way. Because we speak about foreign bodies that enter the body, and we speak about them as different forms of inflammations or viruses, and so on. Also, it’s a way to speak about artificial immunity building, which is a politically charged term because it came from politics – immunitas. It was exempt from a general law. So, it refers to privilege in a sense – to be immune to something. So, for example, these privileged nations that are immune to adversities. Now, this term is overused quite a bit, in politics and in military context. “Immunity is security” if we use the words of Mark Neocleous.

So, it really goes against the idea of “foreigners everywhere”. It does not matter how thick walls you’ll build, it’s a porous world. And it will reach your body in one way or another. So, we speak about the human body scale, but also the planetary body scale.

When coming back to Rožanskaitė, one could say she has dealt with difficult topics, such as aging, diseases, death, loneliness, etc. Also, the depiction of the medical world has not been the most common topic in art history. Curator and art critic Inga Lace has pointed out that Rožanskaitė did not praise the achievements of Soviet medicine, although she used them as material for her works. Perhaps she was not interested in portraying the so-called success stories, but for example, highlighting the tensions of the procedure room, and the weakness and fragility of the human body under study. Could it be said that it’s precisely such sensitive and difficult topics, and the way she approaches them that makes her relevant to both contemporary artists and the (art) audiences today?

And for you, how did she approach these subjects? How close is her vision of the human body and medical themes to you?

NC: I definitely think so. Also, in today’s medical system, which is not a Soviet one, you have this kind of neoliberalized version of it, where everything depends on your income, and how much you can afford to take care of yourself. So, you feel even more isolated and trapped into the system. In our region it’s still more kind of hybrid version – you can have a free healthcare etc. But it’s becoming more and more privatized. There is this idea of entrapment by trying to really take care of your body and health situation.

Since the start of our creative work, the body has always been a one central theme. It does not have to be a human body, it can be a celestial body, or a robotic body, or bacterial body etc. Different transformations of these bodies, and especially their relationship with technology is important. When you think about Rožanskaitė, it is quite obvious that she is a not-lover-of-technology. She really does not like it: she sees it as a threat. But she is almost obsessed with it. In our case, we are more ambivalent of this relationship, because we try to emphasize how technology is not something neutral, it’s not something on its own, it is very much about where it comes from, how it is used, how it is employed and in which context (how it is militarized or used by corporations etc). So, technology is not something neutral, but it is always part of some system.

Pakui Hardware, Inflammation, 2023. Photo: Ugnius Gelguda. Courtesy of the artists, Lithuanian National Museum of Art and Carlier|Gebauer (Berlin/Madrid)

In the late years - at least at the regional level - a clear interest in the works of female artists active in the (late) Soviet period has emerged. The artists who are “rediscovered”, are for example Rožanskaitė in Lithuania, Magdalena Abakanowicz in Poland, and Anu Põder in the context of Estonia. I think the depiction of the body is in some ways similar in these artists works (fragmented, unprotected, alienated, carrying different traumas etc). Why do you think these artists have become so popular? Is it because we have deserted the idea of the perfect body, and are accepting maybe concept of a fragile or even weak body? What are your ideas?

NC: Anu Põder was also one point of reference when we were doing the new works, which were presented in Vilnius and will be presented in Venice. She made those pieces in which she did almost like skeletons out of fabrics, and then she cut out the fabrics to create these translucent bodies.

I think it’s very much connected with showing this fragility of embodied subjects. When you have this obsession with hyper-healthy bodies on one hand, and then you have these ailing and failing bodies on the other... And this is what the “Inflammation” is about too. Because this failure of the body is much about social and economic failure. So, what makes you ill, is that you are “a failure” in life as a social and economic factor. And you can’t afford the healthcare. You are exposed to unhealthy conditions; you have trauma that travels from generation to generation. It’s a body connected to the longer history and to the larger system. And it’s ailing and failing because of that.

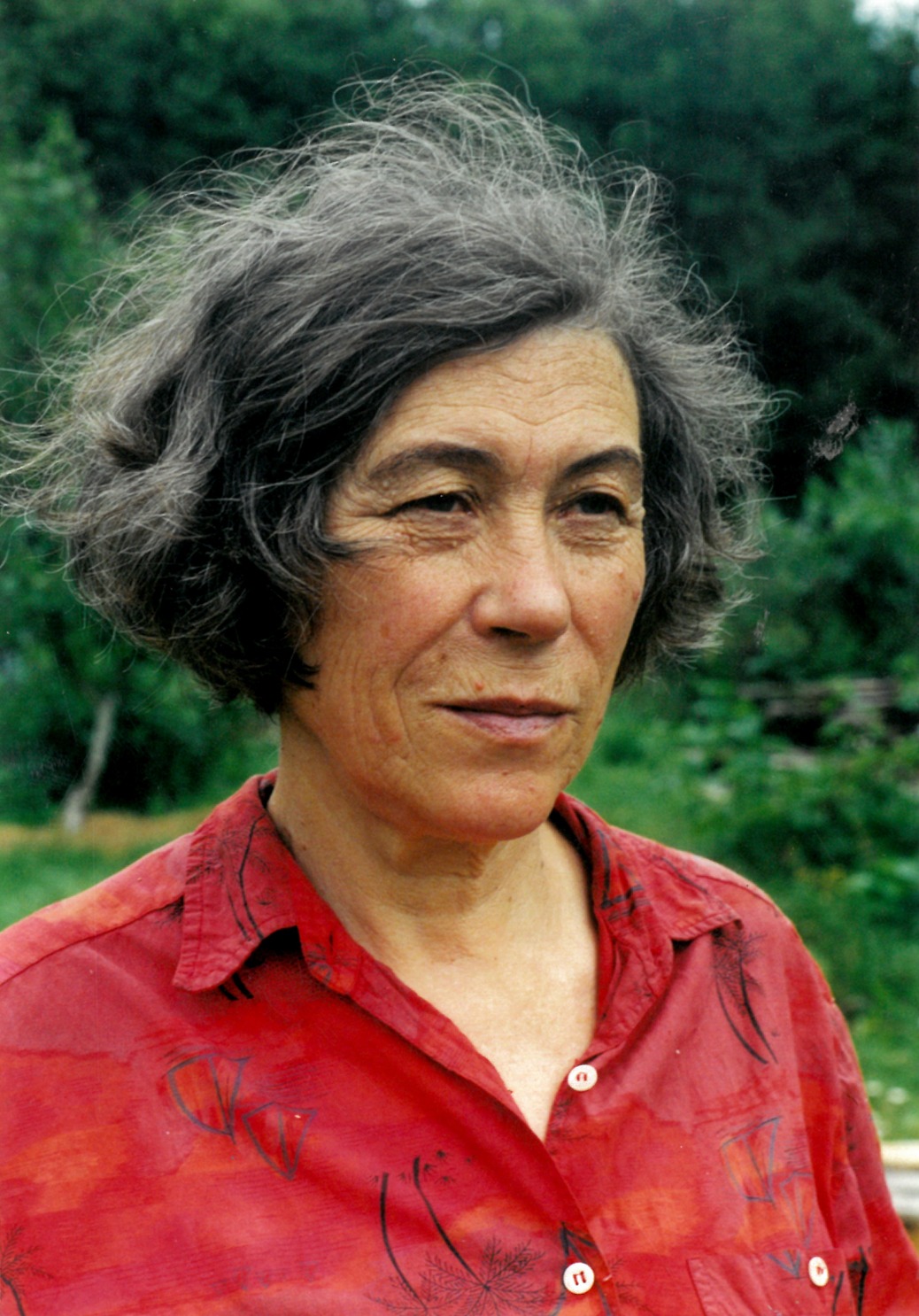

Marija Teresė Rožanskaitė. Courtesy of the artist’s family

While Rožanskaitė was more concerned with the aging body, you have been interested in the topics of rejuvenation and enhancement of the human body to extend its life cycle and quality, or have looked at human attempts at avoiding or countering mortality. One example here is the interest in prosthetics as a material, but also as an idea. How do you perceive this topic: are you genuinely interested in the biological, genetic, etc. enhancement of a human, or is it rather an irony and a desire to show a human’s dependence on science and contemporary social constructs and trends that promote physical health?

NC: For example, we have done an installation using chia seeds which was an irony towards the superfoods and health obsessions. We also have done a project which was called “The Metaphysics of the Runner” which was dealing with different forms of human enhancement, and obsession with fitness that was really picking up pace in society.

When we first started to refer to human enhancement, we were looking at this very technocratic understanding of that enhancement. I think this is where we started critiquing this dualism between the mind and the body, which is obvious in those thinkers and venture capitalists who are working towards building different ways to enhance bodies. Because they always disconnect the mind from the body, and always privilege the mind as such. And so, the body seemed always like some antiquated thing. They also try to see aging as something unnatural, as a disease, although it’s a natural biological process.

This going against nature was always related with bigger systems, such as capitalism, for us. This enhancement was always tied to some kind of efficiency or productivity of the body. As if building super bodies was a way to build more productive society: to extract more profit again and again. It’s kind of a vicious circle. Instead of admitting this interconnectedness of the body to the environment, climate, history, and social situation, they always appear as some kind of vacuum. Which for us is just a very zoomed-in and narrow vision.

Marija Teresė Rožanskaitė, Heart, 1987. Oil on canvas, 130 × 90 cm. Photo: Vidmantas Ilčiukas. Courtesy of the artist’s family

I also want to ask about the aesthetics and visual language of Rožanskaitė. During the (late) Soviet period, there was a certain techno-utopian direction, which was represented in Estonia, for example, by Ando Keskküla, and within which artists were interested in the artificial environment and technical world around us, and in new technologies and their impact on our perception of reality. In a sense, Rožanskaitė’ work falls also in this direction. Is this depiction of the technical world and the aesthetic that comes with it also something that fascinates you?

NC: Yes, it is definitely the case. It was also around the time of cybernetics in the Western art world. This interest in technologies became very prominent and dominant. In Soviet times the artists were taken to these different scientific facilities, and they had to praise technological progress, but she chose this other “quiet” way of critiquing it. But she is also depicting it in obsessive manner and details.

At the same time, there is also a clear distinction of two different generations: a situation where you work with the artist of the past generation and her works, history, and materials. What has this experience for you to work with the past generation been like? And what do you see as possible methods for such cross-generational collaborations for today’s artists in general?

UG: For this project for Venice, it’s more like a dialogue. There are all these technological references and body references. And the way her work will be represented in the installation, is very important as well: it’s going to be an unusual way of showing her work. More like in a contemporary state or setting. In this way, the visitor will experience it totally different way. Maybe it is even hard to say if these works were made in the 1970s or in 2024, because of this form of presentation.

NC: These cross-generational dialogues that are happening everywhere, create in a sense new reading. Art is always in conversation with previous generations, not done in a vacuum. But it can also have an antagonistic relationship with the previous generation, like almost Freudian “kill your parents” kind of way. Or it can be “reviving your grandparents” way as well. (Laughs). But especially now it’s female and non-Western artists that are discovered, because again of this way to finding the more kind of caring way, or more sensitive way depicting the body and for example its relationship to the environment.

Pakui Hardware, Inflammation, 2023. Photo: Ugnius Gelguda. Courtesy of the artists, Lithuanian National Museum of Art and Carlier|Gebauer (Berlin/Madrid)

In conclusion I would ask: what will be the general tone of this exhibition, is it rather hopeful or pessimistic?

NC: It is more like finding hope in misery. (Laughs).

If we speak the words of Haraway, it’s “staying in the trouble” kind of moment, where you know you are in a situation where there is no turning back as such. So, you need to dream. But you also need to be kind of sober, knowing what is ahead of you. And I think the main thing is, not only for the government, but also for people in general, to regain their agency and understand that they have the agency – although at first glance, it might seem as they don’t.

Title image: Pakui Hardware, Inflammation, 2023. Photo: Ugnius Gelguda. Courtesy of the artists, Lithuanian National Museum of Art and Carlier|Gebauer (Berlin/Madrid)