Towards radical hospitality

A conversation with Adam Budak, the curator of the Latvian Pavilion at the 60th Venice Art Biennale, which will feature an exhibition by Amanda Ziemele titled O day and night, but this is wondrous strange… and therefore as a stranger give it welcome.

A Pole who has long lived and worked outside of his country, Adam Budak is not for the first time acting as a curator for the national pavilion of one of the Baltic countries at the Venice Biennale. In 2013, he curated the Pavilion of Estonia, which at that time exhibited work by the post-conceptual Hungarian-Estonian artist Dénes Farkas. Budak’s next linkage with the Baltics took place in 2021, when he joined the international panel of judges that awarded the Purvītis Prize to Latvian artist Amanda Ziemele that year. He was intrigued by her works and her fresh, polyphonic (by the way, one of Budak's favourite words) approach to such a classic and significant medium in the Latvian cultural canon as painting. Subsequently, he participated in the competition for the Latvian pavilion project as the curator of the version proposed by Ziemele. After the project was selected to represent Latvia, Budak actively and enthusiastically participated in its implementation. A couple of weeks before the opening of the Venice Biennale, Budak visited Riga, where the pavilion’s programme was presented to both Latvian and international media. And that's where we met.

Budak is a person with impressively broad cultural horizons. This was facilitated in part by his education – initially in theatre and literature (at the Jagiellonian University in Krakow), and later on, in philosophy, art history, and architecture at the Central European University in Prague. For several years now he has been heading one of the most famous German art institutions – the Kestner Gesellschaft in Hanover. Before that, he was the Artistic Director of the National Gallery in Prague, Czech Republic, and curator of contemporary art at Kunsthaus Graz at the Landesmuseum Joanneum, Austria. The list of exhibition projects he has curated and co-curated is truly impressive. By the way, when Budak was one of the co-curators of Manifesta 7, he invited Latvian artists Miks Mitrēvics and Evelīna Deičmane to participate. Budak has worked extensively and successfully with some of the biggest stars of the contemporary art scene – for example, he has curated exhibitions by Louise Bourgeois, Ai Weiwei, Katharina Grosse and Paula Rego.

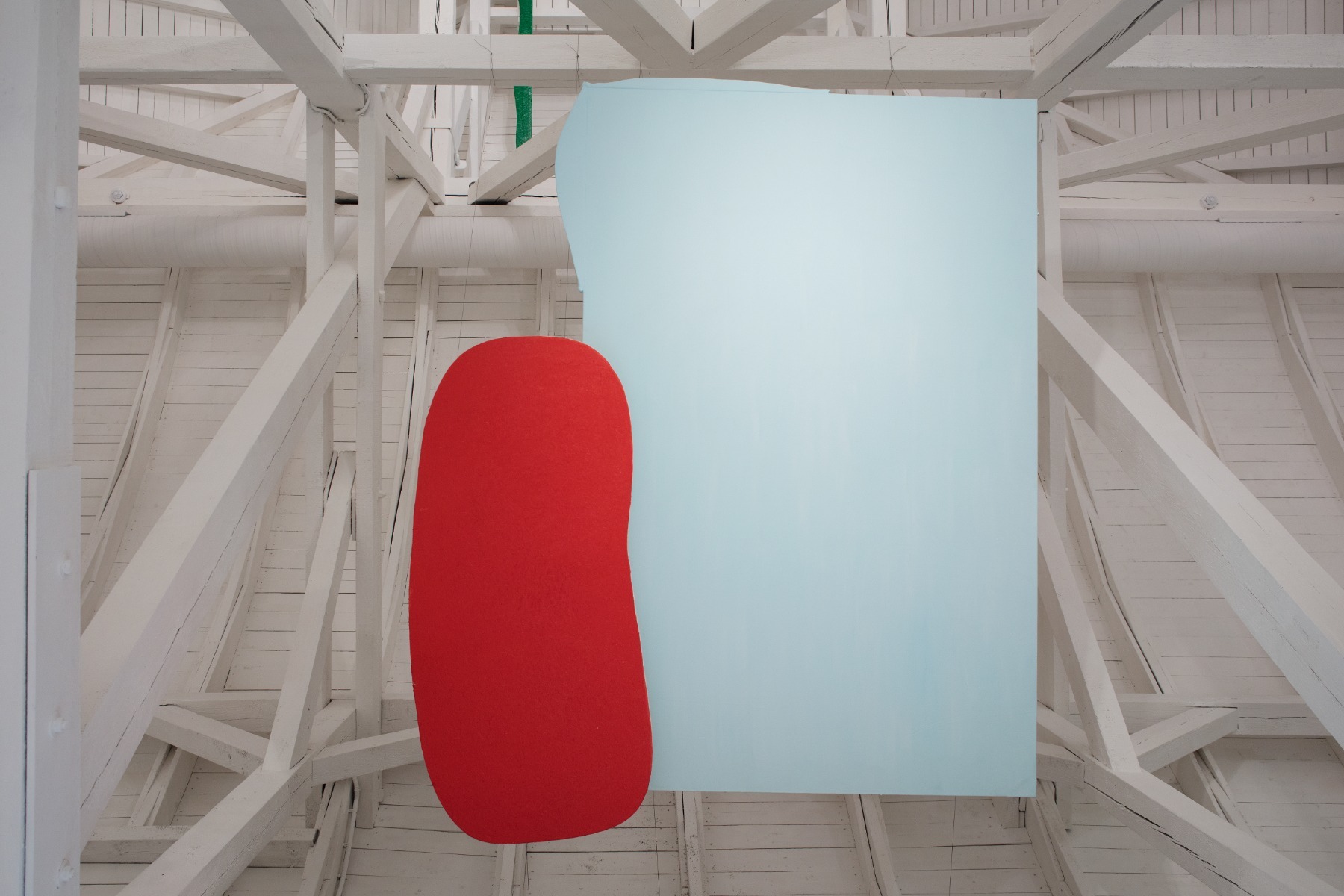

Layout of the exhibition "O day and night, but this is wondrous strange and therefore as a stranger give it welcome" in the Latvian Pavilion. Photo: Oskars Upenieks

During the press conference, Budak speaks calmly and thoughtfully, as if constructing a house from the spoken word (architecture has always been his passion). And here, on the first floor of the TET building on Dzirnavu iela, where the Latvian Pavilion's press conference is taking place, he recounts his initial impressions of Amanda Ziemele's work when he first saw it in 2021 as a member of the Purvītis Prize panel of judges: ‘It wasn't really a painting. It was something much beyond painting, something that we couldn't define. That's why we were so amazed by it; it was love at first sight. The form that Amanda developed locates itself somewhere between painting and architecture, or maybe even performance, so we can call it performative painting – painting that escapes the regular coordinates related to this medium, such as framing or flatness, and liberates itself towards a hybrid form that awaits definition.’

Amanda Ziemele: Exhibition "Quantum Hair Implants" at the Latvian National Museum of Art (as part of the Purvītis Prize 2021 finalists show), 2021

Amanda Ziemele: Exhibition "Quantum Hair Implants" at the Latvian National Museum of Art (as part of the Purvītis Prize 2021 finalists show), 2021

The very attentive interpreter at the press conference momentarily fails to grasp the words ‘polyglot of space’, with which Budak describes Ziemele’s creative method. The interpreter suggests: ‘Queen of space?’ Budak smiles: ‘Yes, you could say that, too...’ Budak could well be called the king of contexts, which he lays down like bricks as he forms the foundation of the pavilion's concept. He and Ziemele have chosen what conceivably may be the longest title for an exhibition in the entire history of the Venice Biennale (it definitely is in terms of the Latvian Pavilion) – it's a quote from Shakespeare, a snippet of the dialogue between Hamlet and Horatio: ‘O day and night, but this is wondrous strange… and therefore as a stranger give it welcome’. Budak explains: ‘Hamlet was about time out of joint, and this is exactly the time that we are living in and going through at this moment. Hamlet is a tragedy of revenge, a tragedy of violence, grief, and power. Our title corresponds with the way Amanda constructs the space as a dialogical and relational act; it is a conversation, an exchange between Hamlet and his best friend Horatio before they come to one of the most important conclusions within this play – the acceptance that this is a world where not even philosophers are aware of what is happening. We arrive at the uncanny, at not knowing what is beyond the philosophers' knowledge. Such is the suspense that we would like to create in the pavilion with the eight forms that Amanda has developed as an attempt to tame the space and to enter into a dialogue with the audience and with whomever encounters or is confronted by these forms. Give it welcome. Upon entering the pavilion, we enter a phantasmagorical zone surrounded by alien, strange, yet familiar forms that imitate someone or something we might know from our own world or perhaps from the world of fantasy and imagination.’

After the press conference, we are led into one of the TET offices, where we settle on a grey sofa and begin our conversation.

Adam Budak and Amanda Ziemele the press conference in Riga. Photo: Kristīne Madjare

I would like to start with the theme of this edition of the Venice Biennale – 'Foreigners Everywhere.' I can imagine it's a really significant subject for you, even in a personal way, because although you're from Poland, you work in a lot of different countries and with artists from different national art scenes. So, do you feel like a 'foreigner everywhere'? Or not really?

That's a great question. Thank you so much. I guess you will never get used to ‘not being foreign’. For over 20 years now I have permanently lived outside of my home country – in places with other languages and cultures. Language is crucial: it really makes you feel different and foreign wherever you are, no matter how well you possess the skills of another language. I feel this every time I come back to my native country, Poland, and feel the freedom that speaking in your mother tongue provides you with. So, language is a very important aspect. Secondly, in the way Adriano Pedrosa points it out, we are all ‘foreigners’. It's not only in cases where you don't live in the country of your mother tongue or your place of birth/origin – we are also foreigners within ourselves. Pedrosa indicates three groups as belonging to the category of ‘foreign’: the indigenous artists, or those that are originally connected with a certain place or site; queer artists, who do not belong to the majority of society; and ‘outsider’ artists – those who never studied art, who have never belonged to the system, or have never participated in the things that make you an artist in a professional sense. You can call those groups marginalised; you can call those groups ‘foreign’ or ‘strange’.

There is this very complicated concept by Freud of ‘the uncanny’ (‘das unheimliche' in German), which basically means ‘not being at home’. For a very long time, it was not translated into English because there was no equivalent to 'unheimlich', which really means 'unhomely'. At home, you know everything because it's your home – everything is familiar to you. But when you're not at home, you feel foreign, or you are perceived as a foreigner – someone who does not belong. Belonging is extremely important. Pedrosa also says that it's kind of autobiographical for him because he is a Brazilian curator and has always felt that he belongs to third-world countries. We encounter this when we travel, when we go through all the different protocols that limit our freedom or make us feel like those who do not belong, who are outsiders in some way. He is also the first openly queer curator of the Venice Biennale, which, of course, makes an impact or will influence his artistic choices.

So all these elements... some of them may even be hidden, not visible, but they all make us foreign. Or make us strange. A stranger is someone you don't know, someone you've never met before, someone you might be afraid of. You need to be generous, willing to meet someone you don't know. And I guess our societies are going in the opposite direction – they’re isolating themselves right now. Again, back to Freud. The 'unheimliche' is also a kind of crisis in identity and knowledge – I think I know you, but actually, I don't know your name. Or, I think we’ve met – a kind of Last Year in Marienbad effect: we’ve met but I am not able to fully recall it – a memory crisis. I don't remember the circumstances, but your face seems familiar – strange, yet familiar. Another translation of ‘das unheimliche' refers to a haunted house – a haunted place, a place of memories that come back, perhaps as a kind of trauma that needs to be healed.

Amanda Ziemele: Exhibition "Quantum Hair Implants" at the Latvian National Museum of Art (as part of the Purvītis Prize 2021 finalists show), 2021

The experience of being a foreigner, entering another culture, is also an experience of communicating with ‘the other’. I think it's quite meaningful in terms of one becoming a fully-formed person – having these other cultures, other languages, other experiences in your life. And in some way, it makes a kind of rhyme with what Amanda Ziemele does with space: the multidimensionality of her works, for me, is also about the acceptance of otherness and strangeness. Could we say that this experience of being a foreigner, or communicating with foreigners, is something that is actually at the core of our contemporary culture?

I'm not sure; I wouldn't call it a tendency. Of course, we are living in an increasingly globalised world. So everything becomes the same; this level of 'foreignness' is being reduced, in a way, because of the freedom to travel and easier access to everything through media, etc… I have to be careful now with what I say when I speak from my perspective as being born in Poland during the communist regime, and as someone who also fled Poland by the end of the 1980s (for what turned out to be only a temporary exile). Two months before the overturn of the system, I happened to be in Canada, and I couldn't imagine coming back, even though communism had already fallen. My parents discouraged me to do so, too. They were born in the system, and they didn't believe that it was not going to work anymore, that is, that there would be a completely different world soon, and that it would last.

I think what seduced us very much when we came to see Amanda's work for the first time at the Purvītis Prize was that it is not what we would imagine to be typical Latvian art. So maybe it's like being foreign to your own tradition. But foreign in a positive sense – as yet another possibility, ‘a remodelling’. I see here a historical connection to those American 1960s and 70s experiments with traditional media. Amanda and her colleague Elīna Vītola once did a Sol LeWitt wall drawing as a reconstruction. This is not typical East European or Latvian art, but something that rather belongs somewhere else. Something that breaks up the (local) tradition. Especially the tradition of painting, a medium that has been pronounced dead many times. And then everybody comes back to it. Painting will never die. It passes through different crises from time to time, often accused of being boring or showing signs of exhaustion on both the formal and narrative level. Amanda’s work is far from being boring. There's a lot of playfulness in it; there are a lot of things that are... almost out of the mind. It’s a kind of freestyle which is very authentic, in a way.

Amanda Ziemele and Elīna Vītola, arranging the exhibition 'Sol LeWitt WD#179' at Gallery 427. 2020

Maybe we can nevertheless speak about Latvian tradition because for Latvians, painting is something very culturally meaningful – a kind of ‘grand medium’. And sure, she may not be following tradition, but she's kind of remaking it, making it even bigger. For me, it's like painting that grows naturally – like a tree, taking its place, following the space, but also creating the form from within itself.

I see it as a kind of combination of architecture, performance and painting itself. And she, on the basis of these three ingredients, is producing something that is still painting per se, but perhaps shouldn't be called painting anymore. Something hybrid, something in-between.

You talked about performative painting at the press conference. But what we see is not the performance; it is a result, isn’t it?

Yes, but I think what makes it ‘performative’ is that it activates you as a viewer. And there is the sculptural aspect of it – it makes you walk around. It follows the principle of sculpture – it's not flat, but rather situated on a base, inviting you to move around it. It is an object in fact. It embodies the ‘theatricality of sculpture’, as Michael Fried once put it. So, you are no longer passive as a viewer; you become active with your own body. I think the body and the body’s movements also play a very important role in this painting.

Work in progress of "O day and night, but this is wondrous strange and therefore as a stranger give it welcome". Photo: Liga Spunde

You were also speaking about the architectural thinking in her approach…

I think it is very intuitive. It's very responsive to whatever architecture has been given – a site-specific painting. At the previous Purvītis Prize exhibition, she almost turned a painting into a frame for a doorway, or let the painting imitate the ceiling. Or the exhibition she had in the Cupola Hall of the National Museum – it was also like displaying the painting, totally ignoring the convention of exhibiting, but enlarging the objects, ignoring the original dimensions, spreading painting all over, making it levitate. An act of liberation is at work. There’s something also naive in her paintings, some elements of almost kid-like scribbles.

When you do an exhibition, you see the wall, and you might want to ignore the doorway because it does not typically belong to the making of an exhibition. But she turns things upside down; she actually uses the doorway and makes it like a portal that you pass through. She adapts the format of the painting to this doorway, and for me, it's really a beautiful and generous gesture. She also doesn't hang her paintings at eye level; they're positioned either up or down, so you have to look for them.

Or in the Biennale project – the forms kind of ‘parachuted’ from ‘whatever’ sky, they found the ground and the floor, and they sat down on it. They sit on the floor; they're not hung – they are leaning against something. Here you doubt your sense of space; you’re not taking it for granted. Space is suddenly not important anymore. The work is in the centre.

From my experience at the Venice Biennale, when you walk through all those rooms, especially in the Arsenale, you walk and walk and walk, with no end in sight, encountering enormous amounts of artworks. Your perceptive capacity is truly challenged. I hope that Amanda will create a break in this monotony through the scattering of these forms – their fragmentation. In one of her texts she wrote about puzzles – you put things together in order to create the whole image; she referred to the writer Georges Perec. Perec was the one who said that ‘space is a doubt’. So that's what I find interesting.

Amanda Ziemele. Exhibiton "Quantum Hair Implants" at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre. 2019. Photo: Ansis Starks

You also mentioned radical tenderness in the context of Amanda’s works.

I was referring to the 2018 Nobel Prize lecture by the writer and Nobel Prize winner in literature Olga Tokarczuk. Tenderness, she said in her speech, ‘is the most modest form of love. It is the kind of love that does not appear in the scriptures or the gospels, no one swears by it, no one cites it. It has no special emblems or symbols, nor does it lead to crime, or prompt envy. It appears wherever we take a close and careful look at another being, at something that is not our “self”’. Especially in these difficult, partly aggressive and war-torn times, the topic of tenderness might become more important and topical than ever. I perceive tenderness as a possible (perhaps utopian) model, a possible modus operandi for the world in ontological crisis and doubt – for politics, art and culture, and human relationships.

In 2022, I curated that other world, the world of the teapot. tenderness, a model, a group exhibition on tenderness at the Kestner Gesellschaft. It embarked on a search for artists as tender narrators and focused on the themes of tenderness, care, and hospitality. The tender narrator is a conscious ‘homo empathicus’ who practices critical intimacy and considers tenderness ‘a way of looking that shows the world as being alive, living, interconnected, cooperating with, and codependent on itself’.

‘The most important thing for me is this accidental togetherness, the surprise encounter in time and space.’ This quote is from Amanda's conversation with poet Agnese Krivade in the catalogue for O day and night, but this is wondrous strange… and therefore as a stranger give it welcome. Amanda transforms the Pavilion's interior into a living organism, taming space, animating dimensions, allowing us, the viewers, to develop a romance of polyphonic space. This is a space of desired welcome, a habitat of hospitality. And here lies the link between tenderness, hospitality, and generosity in her work.

Amanda Ziemele. Exhibition “Sun Has Teeth” in the Cupola Hall of the Latvian National Museum of Art. 2023

I know Amanda not only as an inspiring artist, but also as a gallerist who worked with the Low gallery team. There she was quite physically giving space to others. We also held an exhibition there with my colleagues from the Orbita group. She was really very hospitable in this process, very supportive, and open to our ideas.

Oh, I didn't know that.

In the context of foreignness, with which we started our conversation, what is the role of a curator who is putting together a national pavilion that is not their own country/nation? You once curated the Estonian Pavilion in Venice, and now you’re doing the Latvian Pavilion. What does this perspective as a foreigner bring? Is it a kind of multicultural thinking that provides a framework for national representation?

Well, the national approach at the Venice Biennale is somewhat of an atavism. Perhaps it’s the highest time to rethink this concept. Of course, we all do love the Venice Biennale; yet we all sense that it’s a bit dated, especially with today's socio-political situation, with the understanding of nationality, with multinationalism, with globalisation again, and the whole criticality it evokes. I think that with his ‘foreigners everywhere’ focus on the sense of belonging, Adriano Pedrosa very much hits the point. Where do you belong? This is also about Where do you come from? And how German you are, or how Polish you are, or how Latvian you are. There have been various attempts at questioning this. In the Giardini, the Germans swap pavilions with the French from time to time. This year the German Pavilion will feature an Israeli artist (amongst others). The same artist, Yael Bartana, represented Poland around ten years ago. So here you have a case of an artist kind of migrating from one national pavilion to another, thereby reflecting how difficult this clear understanding of national belonging is. In the previous Biennale’s Polish Pavilion, Małgorzata Mirga-Tas was the first Roma artist to ever be exhibited in a pavilion at Venice. On the other hand, the Venice Biennale, only if approached critically, may be perceived as an opportunity to bring more visibility to marginalised groups as well as to reflect the complexity of ethnic and national definitions.

But how do you feel about what you are bringing as a person coming from another culture but also with a significant international background? What are you bringing into this kind of national project?

A consideration of the national identity [of a project] has never been my starting point. I have always tried to go beyond it, against expectations, towards the polyphonic expression which includes many voices – many identities – articulated simultaneously. Certainly, one of those voices is related to the place one comes from… I hope this aspect is visible in my work. There may always be something that leaves a lasting impact on you from your younger years (but we do not want to delve into psychoanalysis now). This, of course, includes the identity and culture of the place you were born in or where you grew up. I have always searched for a broader context, one that goes beyond the claustrophobic confines of a singular take.

Amanda Ziemele. Exhibition “Sun Has Teeth” in the Cupola Hall of the Latvian National Museum of Art. 2023

I wouldn't say that what you bring into projects is solely the impact of Polish culture. It's more of a mixture of influences from various experiences and encounters that have shaped you over time. This includes the impact of the many artists with whom you've worked, which brings me to ask the following question: How do you choose artists? How do you decide which artists you would like to work with, especially considering they are very different, such as Ai Weiwei and Katharina Grosse?

I look for artists on the basis of my interests and education. My first degree was in theatre and literature. And then in Prague, I studied at the faculty of history and philosophy of art and architecture – a fascinating melange. I smuggled myself in as an ‘art historian’, and found myself sitting in a class with philosophers and architects. Architects made me aware of what space means; they implemented in me a certain sensitivity towards space. Philosophers helped me to understand what concepts are. Those two elements developed into a passion for curating – a profession of working with artists on a confluence of spatial and conceptual practice. Without a knowledge of concepts, and without a sensitivity towards space, you will never be a good curator. These are the most important ingredients.

With the artists you mentioned, the priority somehow shifted to the space. Especially in the case of Katharina Grosse – her work is almost always responsive to the given [exhibition] space and the venue’s architecture. I’ve always enjoyed working in architecturally interesting exhibition spaces that demand and inspire site-specific works. I began in Krakow in a brutalist 1960s building which created a provocative backdrop for the artists’ works and influenced my choices. Then, a pivotal moment was working in Graz at Kunsthaus Graz, a radical, organic feat of architecture by Peter Cook and Colin Fournier – a building that resembles a body, but a body without organs. Everything had to be constructed anew. I love collaborating with the architects. Such is also the case of Amanda's project. The first decision we made was to involve an architect in developing the project. I appreciate the exchange between the artists, architects and curators. In the case of Ai Weiwei, it was rather the relevance of his work which attracted me in the first place. The impressive, monumental site-specific project which he created for the functionalist building of the National Gallery in Prague dealt with the urgent issues of the humanitarian crisis concerning refugees. Addressing those issues was of paramount importance for me.

Amanda Ziemele. Exhibition “Sun Has Teeth” in the Cupola Hall of the Latvian National Museum of Art. 2023

Continuing with that thread, what was the most significant criterion that cemented your decision to work with Amanda?

I think that with Amanda it was the fascination concerning the break with tradition. The belief that we can develop something meaningful together was a driving force. You don't have to be an activist, you don't need to use explicit language – you can also communicate with a less direct vocabulary. Selecting a quote from Hamlet as a title is already a statement. The play revolves around a world that is 'out of joint', a term that resonates with moments of anxiety, conflict, and disputes. This high level of disagreement with the world as depicted in Hamlet is incomparable with any other major narratives of the human mind.

But from this very conflict-filled narrative you have taken a quote that is not about conflict, but about something contrary to it – welcoming the world.

Absolutely. Welcome is a necessary gesture; without it, you cannot solve a problem or conflict. Without welcome, you disqualify or exclude. I think the Biennale will be very much about inclusion as opposed to division, the latter being such a driving force at this moment. I'm not sure to what extent it's going to be a utopian project, or naive, in itself. It’s hard to hide pessimism…

Amanda Ziemele. Exhibition “Sun Has Teeth” in the Cupola Hall of the Latvian National Museum of Art. 2023

It's interesting that you also mentioned healing. If someone needs healing, you first have to welcome them in some way and understand their problems before starting the healing process. Most likely that's what this project is about – welcoming the world and asking: 'What is hurting you?' But do you think that the people who will come to the pavilion will really grasp this idea – will they understand it and feel it?

Hopefully, yes; possibly, no… It's hard to predict people's reaction to any artwork. Artworks speak in a metaphorical language. They convey something that isn't explicit. And our perception is a highly subjective thing. It depends on what you as a viewer bring into it yourself – your experience, the specific moment you are at in your life right now... how the artwork resonates (or doesn't) with you. Giving time for reflection can be challenging in Venice. However, this reflection is necessary to interpret forms that aren't explicitly semantic. If you engage in this work, if you consider these structures – open fields or shelters – as forms of protection, then you can read them as something applicable to what this world is bothered by.

What would you say to a person who is about to enter the Latvian Pavilion to see Amanda's work? What could be the emotional key here?

You are entering a forest of forms that have a very strong theatrical nature. This quite small interior has been turned into a stage. For a moment, you become part of this theatre or performance that is happening in there; you are surrounded by these forms, the main protagonists. The artist has given each form a name, as if it was her own baby...as if, without a name, it wouldn't work anymore. It means that a certain care has been given to these forms, a tenderness. The space is embracing you, literally.

Work in progress of O day and night, but this is wondrous strange and therefore as a stranger give it welcome. Photo: Liga Spunde

So, welcome to the forest.

Yes, welcome to this enchanting forest which, as you will see, is a little bit of a surreal dreamland. Amanda claims that the processes of thinking and painting are intertwined. She recalls childhood moments when she was trying to turn her thoughts into dioramas. What you will encounter in Venice is also a kind of diorama, a place for sensing and thinking. With those three-dimensional forms and you as part of it.