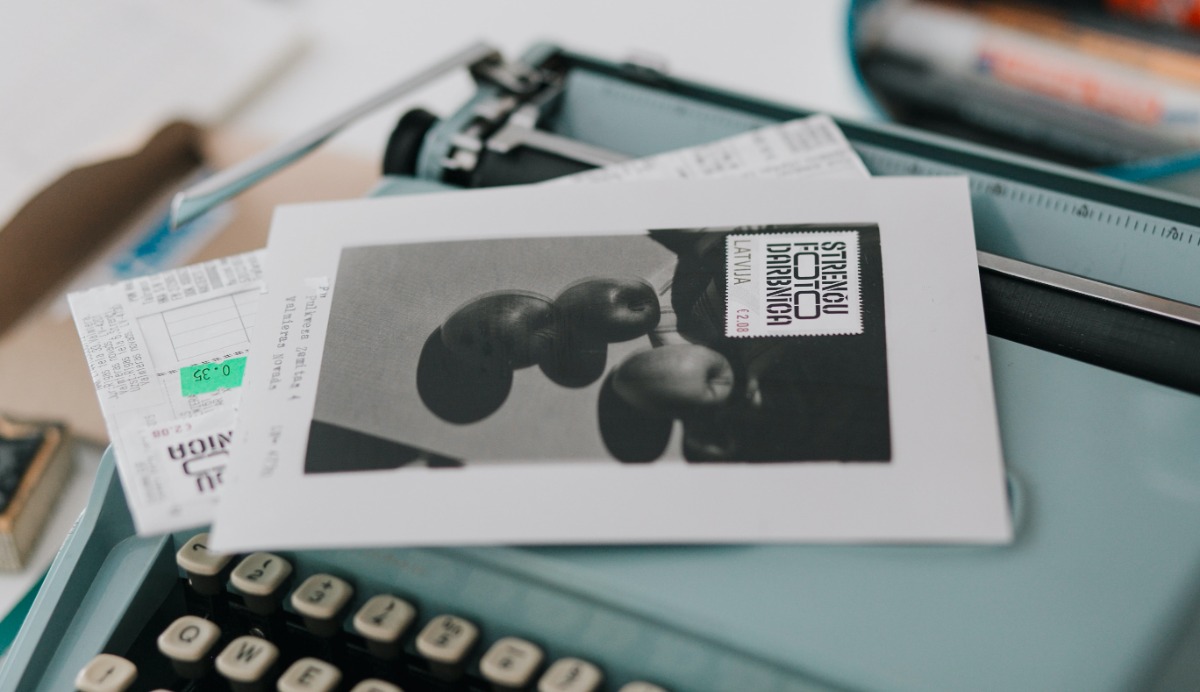

Feel it, Touch it, Smell it, Send it

A Conversation with Belgian Photographer and Mail Art Enthusiast Thomas Vandenberghe

In the mid-1950s in America, an artist named Ray Johnson began sending letters and packages to his friends, acquaintances, and even complete strangers. These weren't ordinary letters, but small artistic works comprising handwritten or typewritten texts, drawings, and collages made from illustrated magazines. They also included small photographs, pieces of colored paper, and other similar items, all pasted onto the same sheets. As a result, Ray began receiving equally artistically crafted messages in return. The list of his correspondents expanded from dozens to hundreds, leading to the creation of one of the first mail art networks, initially named The New York Correspondence School.

Other artists and artistic communities also began to create their own mail art networks. Here, no investments were required (except for paper and postage stamps), no critical acclaim was needed to consider oneself a mail art artist, and no galleries were necessary to present one's visual ideas to others and receive feedback. Mail art as a distinct form of art flourished in the free-thinking and pattern-breaking era of the 1960s and 1970s. It was a form of international artistic exchange that included artists who lived and worked behind the Iron Curtain – in Eastern Europe. In this exchange actively participated such a significant figure for the Latvian art scene as Valdis Āboliņš, an artist and curator, who lived in West Berlin. In 2019, The Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art released an excellent book about him, which includes many examples of his artistic messages.

Thomas Vandenberghe

In the 1990s, the popularity of mail art began to wane. The Iron Curtain rusted and fell, and public interest shifted towards the burgeoning possibilities of electronic media. The internet, originally a fertile ground for network communities that shared principles with mail art networks – and were even called mailing lists– started to evolve. Soon, the networking approach pioneered by artistic communities was co-opted and monetized by social media giants. Mail art seemed to be relegated to the past. However, similar to how the fast-food wave spurred the slow food movement, artists – and indeed, non-artists too – began to explore 'slower,' potentially richer and more nuanced forms of communication.

Thomas Vandenberghe

Contemporary Belgian photographer and mail art enthusiast, Thomas Vandenberghe, began his journey by sending letters to himself. He would mail himself printed photographs to review them with fresh eyes a few days later. This practice evolved, leading him to send his creations to others and consequently fostering the growth of a network of recipients, correspondents, and like-minded individuals. This network primarily consisted of members from the photography community interested in the tangible, analog format of photography, though it was not exclusive to them. Vandenberghe is sure that anyone can become a mail art artist and a member of this vibrant community. This concept was further emphasized during a mail art workshop organized by the curators of the Strenči Photography Workshop, Anna Volkova and Vladimir Svetlov, in late May in Strenči, as part of the program implemented there by 'Orbita.' They invited Vandenberghe to lead the workshop and to share the practices and methodologies of this very democratic form of artistic communication.

The participants' mails from this workshop will be showcased at the end of August in a special exhibition in Strenči. But even now anyone interested can join this exchange (the address will be provided at the end of this text). I was very curious to learn more about the art of "slow communication" based on analog photography – Thomas's approach to the mail art – so I invited him for a talk along with Vladimir Svetlov and Anna Volkova during one of his last days in Latvia.

Thomas Vandenberghe. Photo: Maarten Kinet

I really love this quote from Ray Johnson: 'Male art is not square, a rectangle, a photo, a book, or a slide. It's a river.' So, how did you get into this river? What were your first experiences with it, and why is this river meaningful to you?

Thomas Vandenberghe: I think it was always there, but it didn't come out because it wasn't something from my generation, actually. So, I was just doing my own practice, engaging in photography, and using digital correspondence like everyone else my age. It all started with a text from a Dutch magazine that regularly published articles about new kinds of photography. This particular story was fake, but I really believed it. It described how someone discovered Robert Frank's contact sheets in a private collection. Back in the 70s and 80s, many photographers frequently communicated with each other, sending pictures or even contact sheets or strips by mail. The article claimed that there was a secret code discovered by photographers, allowing you to write with photography. For example, a diaphragm setting of 8 represented the letter A. I was blown away by the story. Later, I contacted the publisher of the magazine and expressed how inspired I was, wanting to meet the author to learn more. The publisher just started laughing and said, 'Amazing! But the story isn't true.'

Anyway, I was so captivated by this story and by the community that photographers had back then, that I began to relate it to myself. I realized that I'm already living in that kind of community, but we communicate in different ways. For example, my town in Belgium is quite small. Yet, a lot of famous artists live in Ghent. We all know each other, connect with each other, and even go out for beers together. However, we always work alone. We socialize over drinks but never work on or discuss our projects together. This realization made me wonder why we, as artists, always exist on our little islands.

I'm also an avid art collector; I love having art in my house. While I enjoy collecting pieces from others, most artists don't have the funds to collect art themselves. Mail art particularly fascinated me because it offers a way to acquire beautiful works for free from various artists and non-artists alike. Every letter is a piece of art –you can frame it, hang it on your fridge, or even devote half of a wall to displaying the postcards you've received.

I then learned more about the mail art movement, which was closely connected to the Fluxus movement. They were against traditional displays of art on walls and in museums, which they saw as elitist. They believed that art is about the artists themselves, not just the works displayed; it's about how artists live their lives and handle daily matters. Art, in essence, is living your life, which is the greatest work of art you can create. This insight was also a catalyst for me. I had been engaged in photography for quite some time, and I began to feel a bit bored with the same medium, wanting to use it in new ways. Then, during a period of depression, when I was often confined to my home with little energy to go out and shoot, I found solace in taking photos of flowers and my surroundings. Due to the analogue process, there was a significant delay. For instance, I might shoot 36 images in a week, develop the film, and only get prints two weeks later. That's when I started sending the pictures to myself. I live in a large apartment with the postal boxes right next to my building. So, every morning, I'd go downstairs, take the daily mail out of the box, and even though it just came back to me, it had gone through the entire postal circuit.

Thomas Vandenberghe

It went first to the central post office…

T.V.: And from there, it traveled through the various stages of the postal system before returning to me with a delay of two to three days because I use only regular stamps, not priority ones. Receiving mail from myself every day brought a bit of happiness and excitement as I opened my mailbox. It also allowed me to reflect on how I felt two or three weeks earlier. I continued this for several months and eventually organized an exhibition when I had accumulated a lot of works. However, corresponding only with myself eventually became boring.

And I decided to build my own network, starting with an announcement on Instagram. Initially, you could send letters to known friends who would send you something back, but that kind of network is quite small. I wanted to expand this network significantly and include people who had been involved in mail art since the 1970s. I aimed to correspond with people internationally. So I put a lot of effort into growing my network. I leveraged everything at my disposal, using Instagram to request addresses with messages like 'please, can you send me your address?' Additionally, there are websites where you can leave your address or find others'. Within six months, I had grown a substantial network, and I think it's only going to get larger and more unwieldy. And what will I do with all the works? Perhaps they will become a book someday. However, I also believe that mail art should be displayed on your wall or stored in a box – to be revisited years later, maybe even after a decade.

Thomas Vandenberghe

But what if you completely change your mind in 10 years?

T.V.: I don’t know what the situation will be in 10 years, or what my interests will be then. It’s possible that I might even grow tired of mail art. However, many of the people I'm corresponding with also engaged in mail art back in their day. For them, it was a significant part of their generation, and they were very passionate about it. Interestingly, my engagement seems to have rekindled their interest, and now they're actively involved in it again.

But what really is the difference between mail art then and now? It seems that for the generations of the 1970s and 1980s, the most meaningful aspect was creating a network of like-minded individuals, almost a parallel society. Today, however, building networks is relatively straightforward –digitally, we can develop them in numerous ways. Perhaps what is more intriguing for us today is the idea of slowing down communication, introducing some delay. Just like in music, where using a delay can make the sound richer and deeper, here too, delay may enrich the meanings of our communications and deepen them.

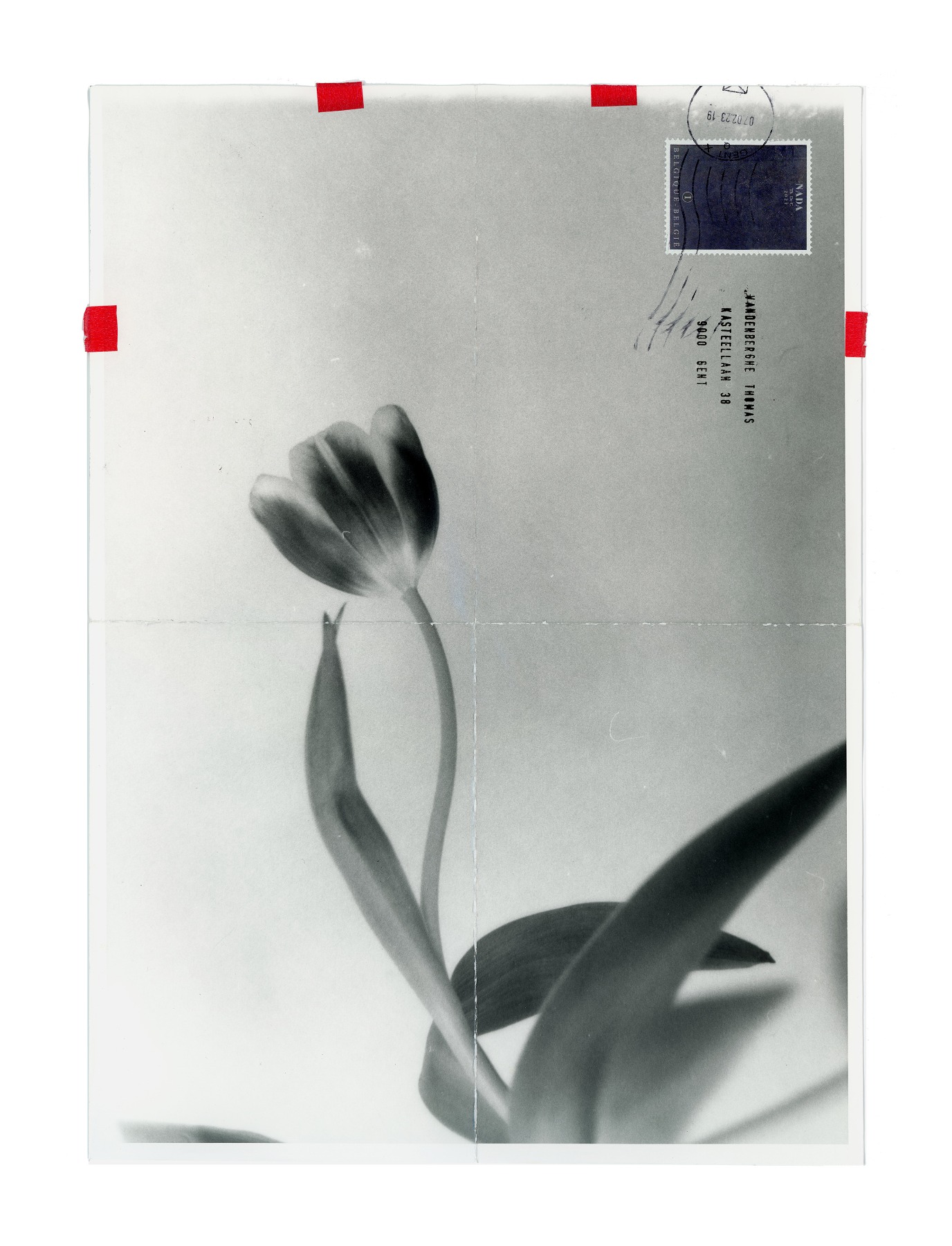

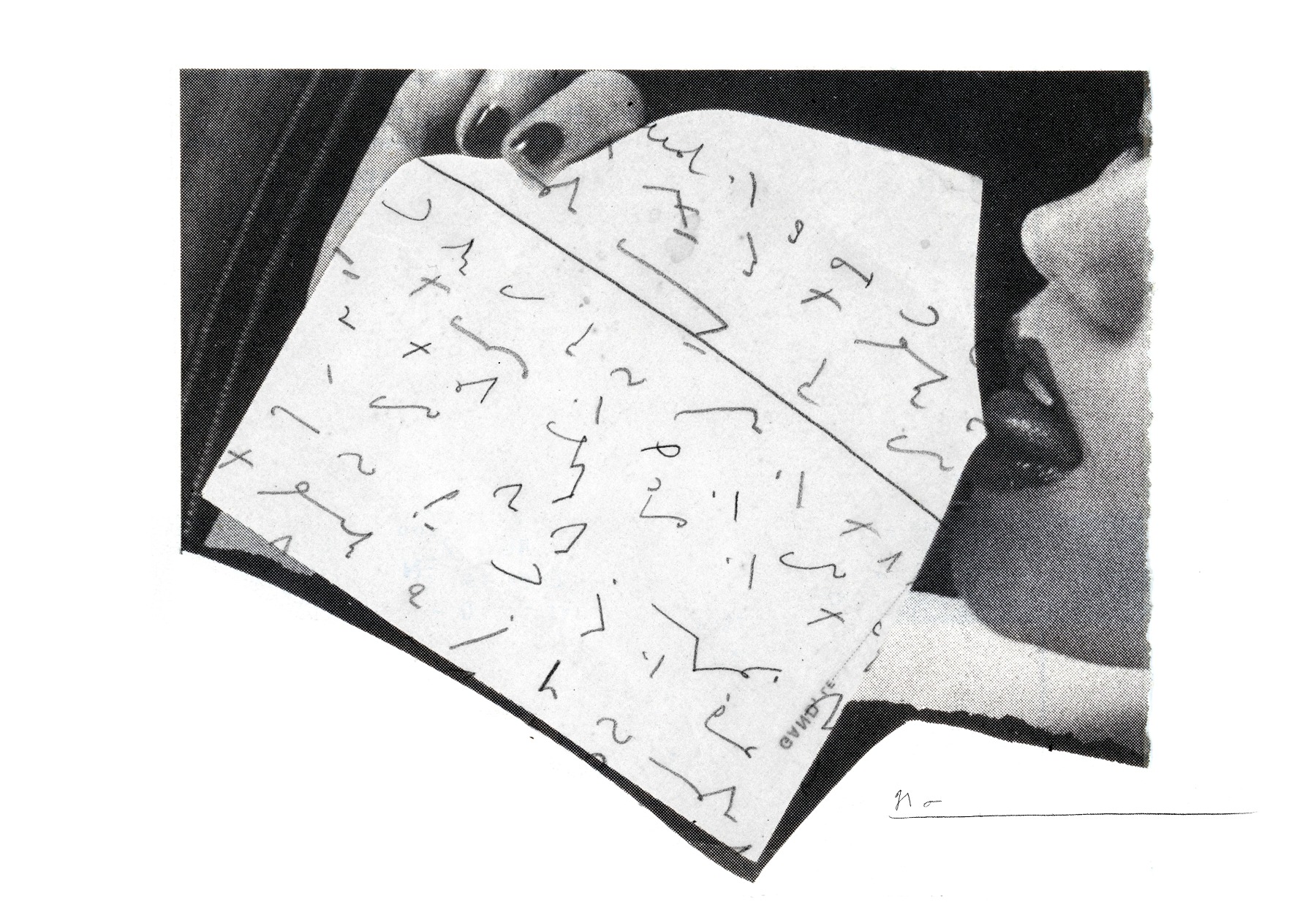

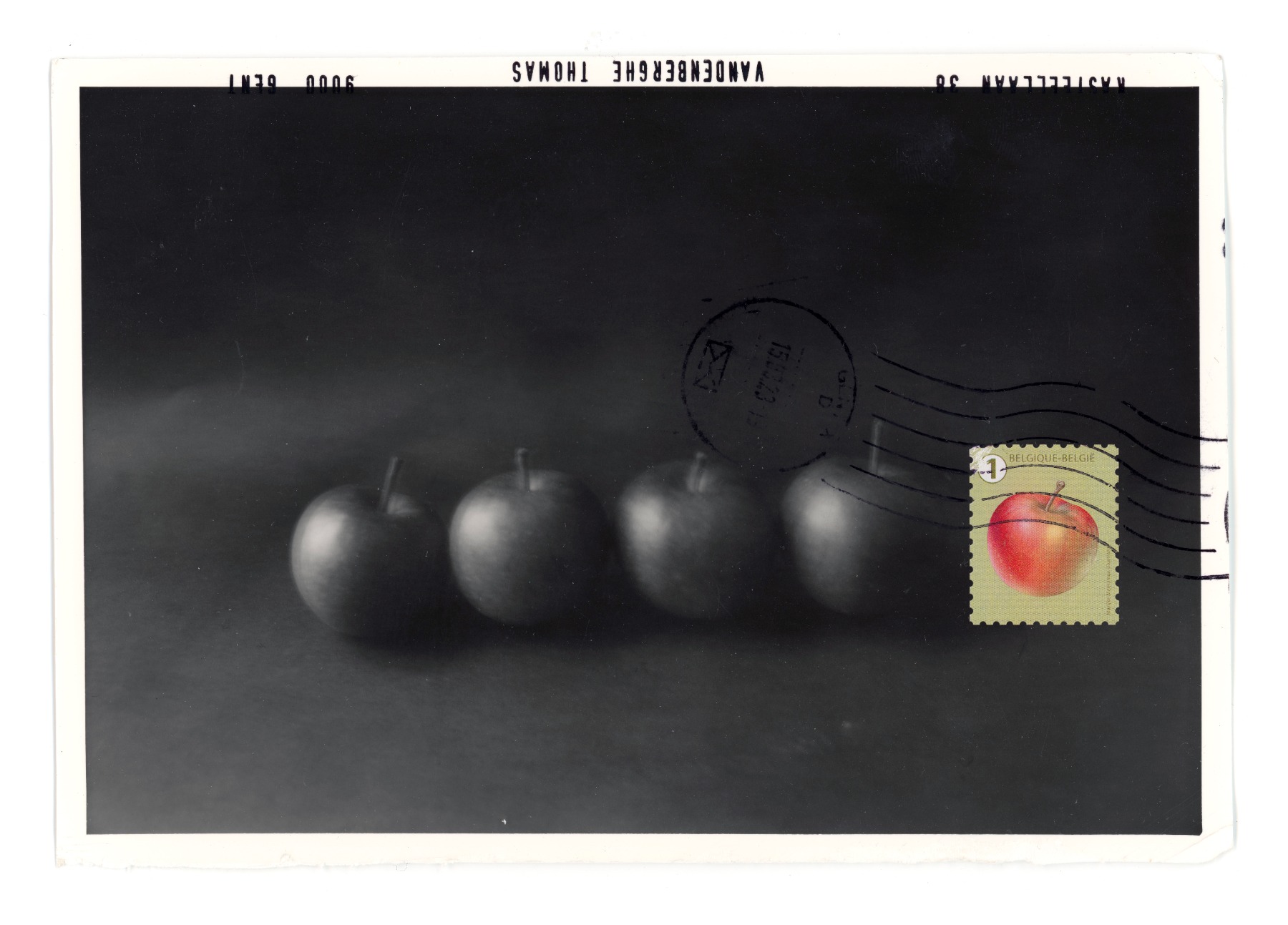

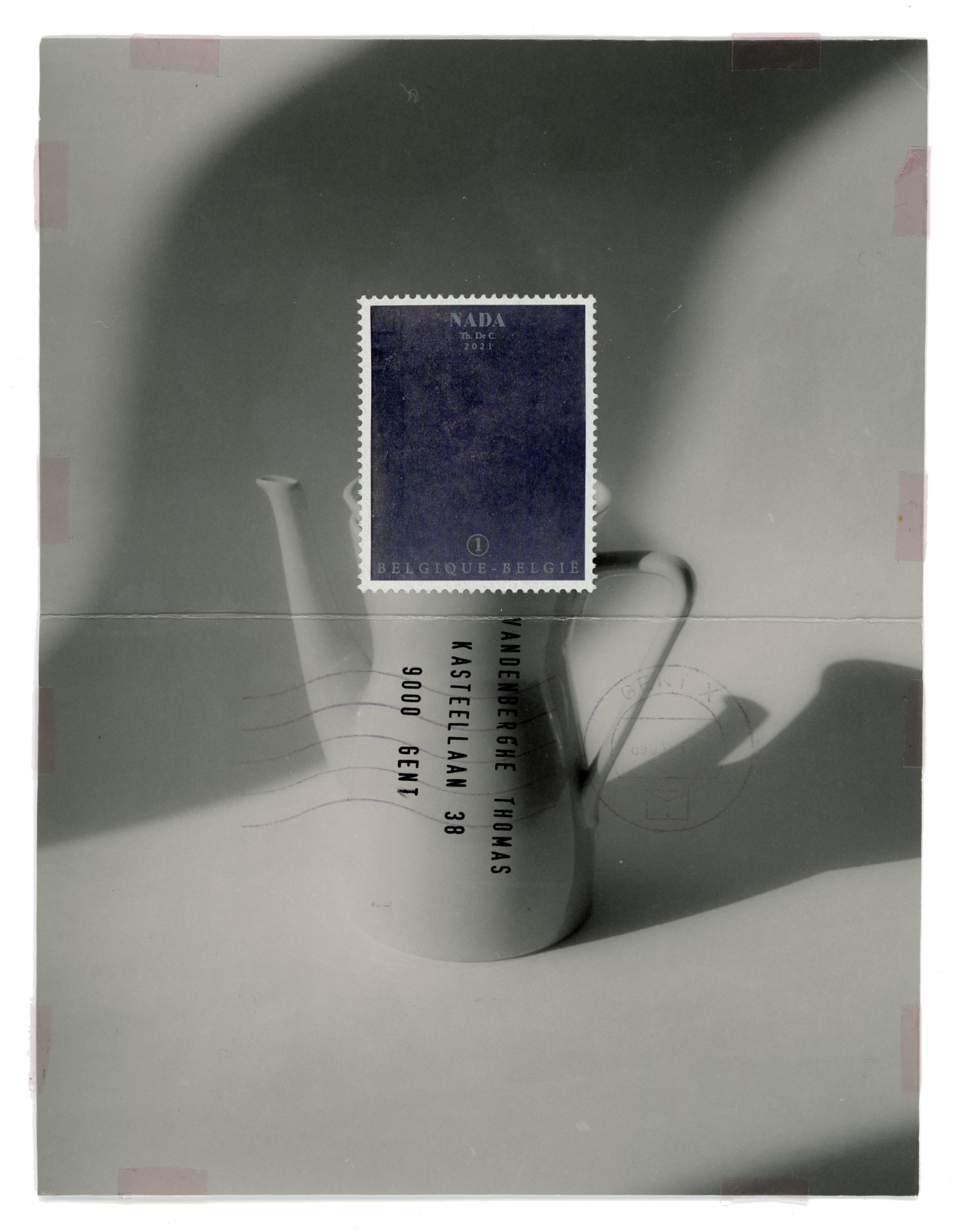

T.V.: A crucial aspect for me is the uniqueness of each artwork; I create pieces that are intended for one recipient only. The materiality of pictures is paramount to me – I need to feel, smell, and interact with the photographs. I enjoy handling negatives, touching prints, writing on them, and even burning them; the physical material is incredibly important to me. This is a major reason I engage in mail art. While digital connections can be made on many levels and are more efficient, they lack the tactile experience. If my phone dies, I lose all that digital communication. But with mail art, I can revisit all the past communications. So yes, it's largely about slowing down, but it's also deeply about the material – touching and feeling it. Additionally, the journey through the postal services influences this materiality; letters acquire marks, sometimes get damaged, adding to their character. Or just get lost.

Photo: Baiba Zvejniece

It's also stimulating photographers to think more about the materiality.

T.V.: Sure! Many photographers today focus predominantly on digital formats; they rarely print their photos, only doing so for exhibitions, or they no longer create test prints. A lot of my friends have mentioned to me about our correspondence, 'It's cool because I made a test print and really liked the format, and maybe I'll make the official edition that size.' There seems to be a declining interest in experimenting with paper, sizes, and other physical aspects of photography. Mail art provides a compelling reason to revisit these practices. In my own mail art works, I often use my 'bad' prints – those that are overexposed, underexposed, or just test strips. In the past, I discarded them because they were useless. Now, I save every piece, as each one could potentially be incorporated into my mail art. Sometimes, others also contribute to your work, adding another layer and sending it back to you.

Photo: Baiba Zvejniece

I've been thinking that this process also somehow reminds me of tattooing reality, imprinting on materiality. When you create a print, it resembles a body, and the modifications you make – adding markings, colours, and special stamps – are akin to applying a small tattoo. Each alteration, much like a tattoo, permanently alters and enriches the character of the original print.

T.V.: Yes, even the postal stamp serves as a mark. This process might also be linked to asserting your presence in the world. Essentially, by sending a letter, you’re declaring, ‘I did this’ or ‘I was here,’ leaving traces of yourself with others. There’s also a significant dose of humour involved. For instance, Ray Johnson once sent a letter to Christo, the renowned artist known for wrapping objects and buildings. Johnson wrote, ‘I really want to buy a piece of your work, but I don’t have any money. What can we do?’ In response, Christo sent him a package that was wrapped (as any usual postal sending). When Johnson opened it, he found only a photograph inside, with the message: ‘Now you've destroyed the work, but you still have the picture.’ So – yes, humour is very meaningful in mail art.

Thomas Vandenberghe

But can we discuss the artistic quality in mail art – is it meaningful, and how can we define quality in this context?

T.V.: There is no definitive quality; there's nothing inherently good or bad. Sometimes, I receive the most remarkable pieces from non-artists because they approach it differently, and often, professional artists overthink their contributions. I believe the best mail art emerges when you don't overthink and simply create something.

Participants during the Mail Art Workshop in Strenči. Photo: Baiba Zvejniece

I would also like to ask Anna and Vladimir about the idea of conducting a workshop in Strenči. This is certainly not your first project associated with this small Latvian town. Initially, there was the book 'Glass Strenči,' which focused on the heritage of glass plates produced in the 1920s and 1930s at the local photo studio. This was followed by a workshop and an exhibition last year in the same space, once the former photo studio. Now, you're turning to mail art…

Vladimir Svetlov: We believe that this method of communicating through photography is actually very traditional. Historically, the primary function of a photography studio was to produce pictures for clients who visited the studio. The majority of these pictures were then mailed to friends and relatives. This method of communication was a natural extension for the field of photography.

Anna Volkova: We are deeply engaged with Strenči, a place that housed a significant photo archive. Locally, photography is often viewed as a meaningful practice related to the past. However, for me, the core purpose of photography is to capture an image of someone, to photograph a beautiful moment, and then send it to someone else – to share that moment, not just to store it in an archive. Therefore, we have been considering ways to foreground this idea of communication in our new project.

Participants during the Mail Art Workshop in Strenči. Photo: Baiba Zvejniece

Participants in the workshop were primarily from Latvia, but I believe they were not exclusively artists in their daily practice.

T.V.: I consider them all as artists. But some of them do other things, yes. For instance, one of the attendees was a history teacher from a local school.

A.V.: She switched now her pupils to writing letters!

You've taught the participants a lot, I believe, but did you learn something from them?

T.V.: I think I imparted my passion to them, and they taught me about their sense of freedom, their uninhibited approach to starting anew. I also picked up many ideas — for example, someone began scratching on a picture, which really struck me. I thought, ‘Oh my god, yes, I had completely forgotten about that technique!’ So, I started scratching as well. It was a very organic and dynamic process. I felt like I was just one of them, contributing only my energy, my way of seeing things, and my approach to photography and mail art, which are deeply personal to me. During the workshop, I also discovered many new analogue photography techniques. The darkroom works were supervised by Armands Andže from the Baltic Analog Lab, who is a master of analogue photography processes.

Participants during the Mail Art Workshop in Strenči. Photo: Baiba Zvejniece

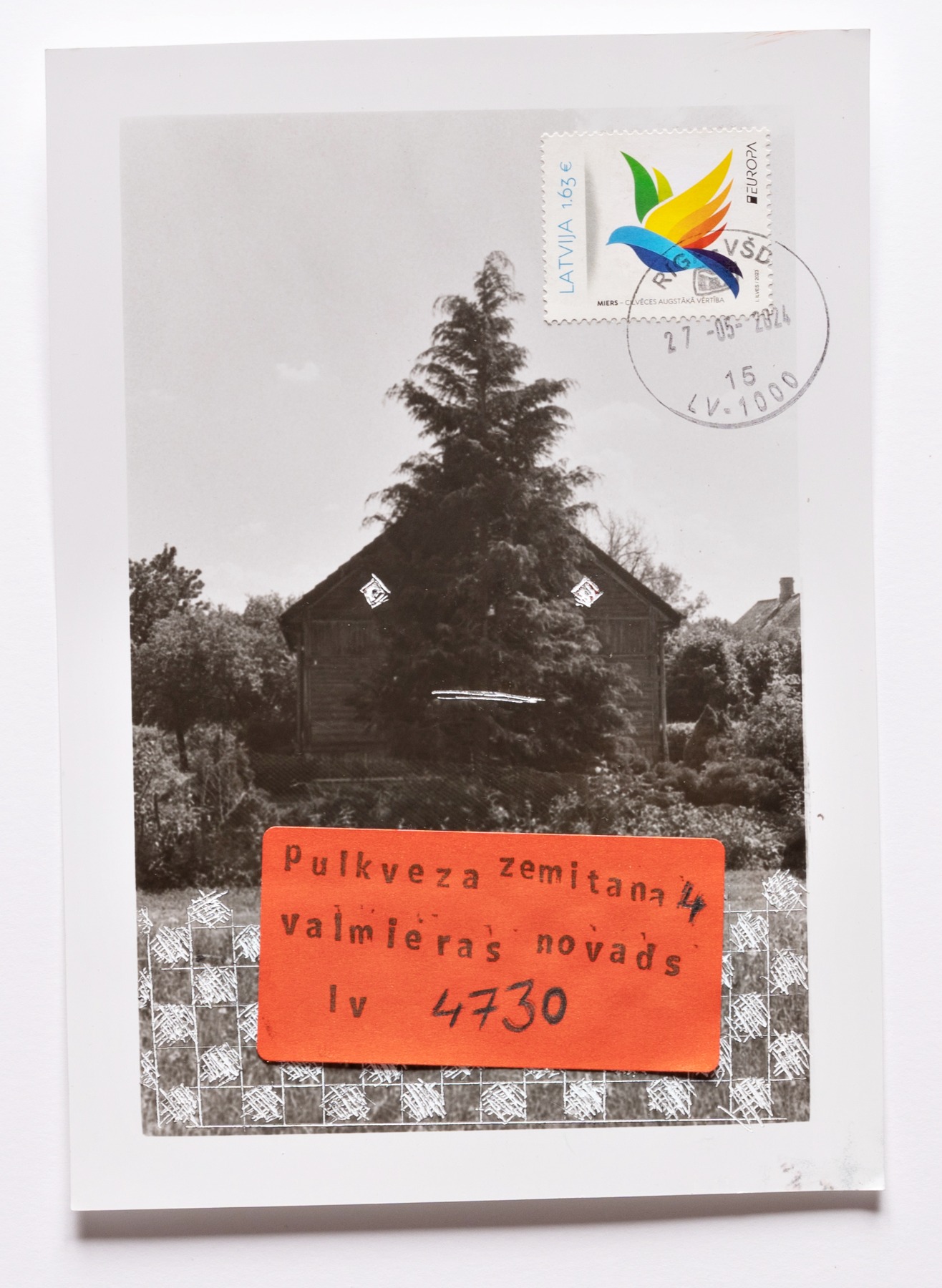

And what will be the outcome of this workshop? There will be an exhibition planned for August, right?

T.V.: I hope so. But first and foremost, I would love to organize a Strenči Correspondence Club. I plan to initiate some open calls to get it started. I'm really captivated by the idea that Strenči, a small town, could become something very international. Imagine people saying, 'Okay, we have an address here,' and sending letters from all over the world to this one spot. Maybe I'm too romantic, but I think being too romantic is a good thing. And that would be the most beautiful outcome of the workshop.

A.V.: I really love the idea of shifting the enthusiasm of Strenči inhabitants from merely archiving photography to actively communicating through it, especially since they are undoubtedly active and open individuals. We share this enthusiasm. I remember, Thomas, seeing you standing outside at 11 o'clock at night, smoking and marvelling at how people inside were still energetically working.

T.V.: Yes, there was really good energy!

Photo: Baiba Zvejniece

Design your letter in a way that seems interesting to you, include some fragments of your life, what's around you, and send it to the address: Strenču fotodarbnīca, Pulkveža Zemitāna iela 4, Strenči, LV-4730. Letters can include photographs, drawings, poetry, and more – in any format, as long as it fits in a mailbox. You can also send your messages to the postal addresses of the mail art workshop participants, which are available on the website fotodarbnica.lv. It’s important to note that mail art avoids curatorial approaches, subjective selection of what's "interesting" and "not interesting" – if you consider something important and curious enough to share with others, then it is. Therefore, all works received by August 1st will be featured in the exhibition opening in Strenči August 24.