Against Simplest Narratives

An interview with Martí Manen, a curator, art writer, and active figure in both the Spanish and Scandinavian art scenes – discussing shifts in our societies and cultures

Martí Manen (born 1976, in Barcelona) is a curator and art writer currently living in Stockholm. Since 2018 he has been the director of Index – The Swedish Contemporary Art Foundation and in 2024 he became a codirector of this institution (together with Isabella Tjäder). He combines experience and knowledge of two art scenes, Spanish and Scandinavian, which seems to be a very successful combination. While living in Spain, he co-founded A*Desk, one of Barcelona's leading independent platforms for art criticism, and curated exhibitions for both major institutions and independent spaces. In 2015, he curated the Spanish Pavilion at the 56th Venice Biennale, and in 2019, he was the curator of the 10th MOMENTUM biennale in Moss, Norway.

I met Martí this autumn in the Lithuanian capital at the ArtVilnius fair. This year, the fair's team not only celebrated its 15th anniversary but also focused on contemporary art from the Nordic countries. Martí was a member of the fair jury and presented a video work by artist Nina Sarnelle, exhibited in the traditional part of ArtVilnius – Project Zone. The work was previously shown in an exhibition at Index, which explored the concept of distribution. “Nina Sarnelle’s film is based on research about expectations and how companies like Amazon arrive in a city, saying, ‘We’re going to build a distribution center here and create 1,000 jobs.’ Then municipalities, states, or regions respond by offering tax breaks and saying, ‘Everything is for you.’ But often, nothing happens – or at least not as promised. Fewer jobs are created, or the distribution center is relocated to another area where the tax conditions are even more favorable for the company,” says Martí.

In our conversation, we also touched on topics directly related to art but extending far beyond it. Why is there a conservative shift in the societies of many countries? How does the art scene in Sweden respond to attempts to reduce state support for the arts? How is the ever-growing competition in the art world being influenced by artificial intelligence? As this interview is being published at the end of the year, it feels like we are summarizing some of the key tendencies shaping the world around us.

Martí Manen at the ArtVilnius'24. Photo: Mika Savičiūtė

Let’s start with your personal story. You were born in Spain, in Barcelona, and became an art critic and curator there. And then you moved to Sweden started working in this country.

It’s been many years now – seven years at Index. Before that, I spent a couple of years working with public art at the Swedish Art Agency, and prior to that, I curated the Spanish Pavilion in Venice, though I was already based in Sweden at that time.

Was it a professional decision, or was there a personal reason behind it?

It was a weird thing. I was working as a curator in Barcelona, also involved with a gallery there. And I thought, okay, I want to experience something different and observe other structures and ways of working. The logical move might have been London or Berlin, but I was particularly interested in how things operated in the Nordic countries. I received a grant to do research, and suddenly – it’s been 20 years here. There's something that holds my interest in that system, one that truly believes in artistic practice and provides support for artists. Institutions are seen as public resources, which is important to me. There’s a belief in the artistic process as something that not only defines society but also serves as a space for questions and critique. This doesn’t mean it’s absent in Spain, but Spain has a different tradition regarding the role of art.

So in Spain art is more like…

It's still a young democracy – less than 50 years as a democratic country. Traces of the dictatorship remain, and the art there often takes a defensive stance, perhaps due to its potential to provoke or disrupt. It's also interesting and it's also a good position – we have to be ready in case something happens. In Sweden, on the other hand, there’s an assumption that art holds intrinsic value. Spain, of course, has a remarkable tradition; if you wish, you can see the works of Goya or Velázquez. It's another kind of genealogy there than in the Nordic countries. I like moving between these two perspectives, drawing on references that resonate in the North while also bringing ideas back to Spain. This position allows me to move between ways of thinking, sharing insights from both sides.

In Spain, museums developed later than in other parts of Europe. And the democratic structures are pretty young. It doesn't mean the museums are lacking – Museo Reina Sofia is outstanding, and MACBA is a museum that has been steadily growing. And of course, there's the Prado, with its incredible royal collection. Yet, there’s a certain contextual fragility regarding support structures for artists. In the Nordic countries, support was historically guaranteed, though this, too, is changing. Now, we’re seeing these systems being questioned daily, especially around the role of contemporary art in society. We’re in the midst of a shift right now.

Bodies and Antibodies. Exhibition view, Index, 2023-24

Do you have a sense of where this shift is heading? What direction do you think things are taking?

Absolutely. You can see it reflected in state budgets, in how certain politicians speak, and in the increasing prominence of conservative perspectives. There’s also a growing tendency toward cautious language – it's often easier not to address certain topics to avoid complications. For me, this is deeply concerning, as it suggests a normalization of self-censorship as a survival mechanism. It’s directly linked to politics. Internally, this is quite pronounced right now in Sweden, where the government coalition includes the Sweden Democrats, a party with Nazi roots. Before the election, they explicitly proposed zero funding for contemporary art, so their intentions are clear. Though they haven’t fully realized this goal, you can see that there’s a persistent drive toward it.

Simultaneously, a positive shift is happening within the arts community. There’s a stronger dialogue among individuals and institutions. As a co-director of Index, for example, I engage in ongoing conversations with other organizations to share ideas, support each other, and create platforms that highlight the value of our work. It’s fostering a stronger, more unified community, which is essential in times like these.

So, if there’s pressure, then there’s a community.

Yes. And then, by being together, you become aware of the potential that's there. It’s happening more now than before, even on practical levels – we share materials, resources, information. In a way, this is a positive outcome of a difficult situation. This feeling of community is rewarding, too. It's a special moment, and we'll see what happens; in two years, there could be new elections, a new government, and things might change for the better. But it’s important to stay aware of what’s going on and to speak up.

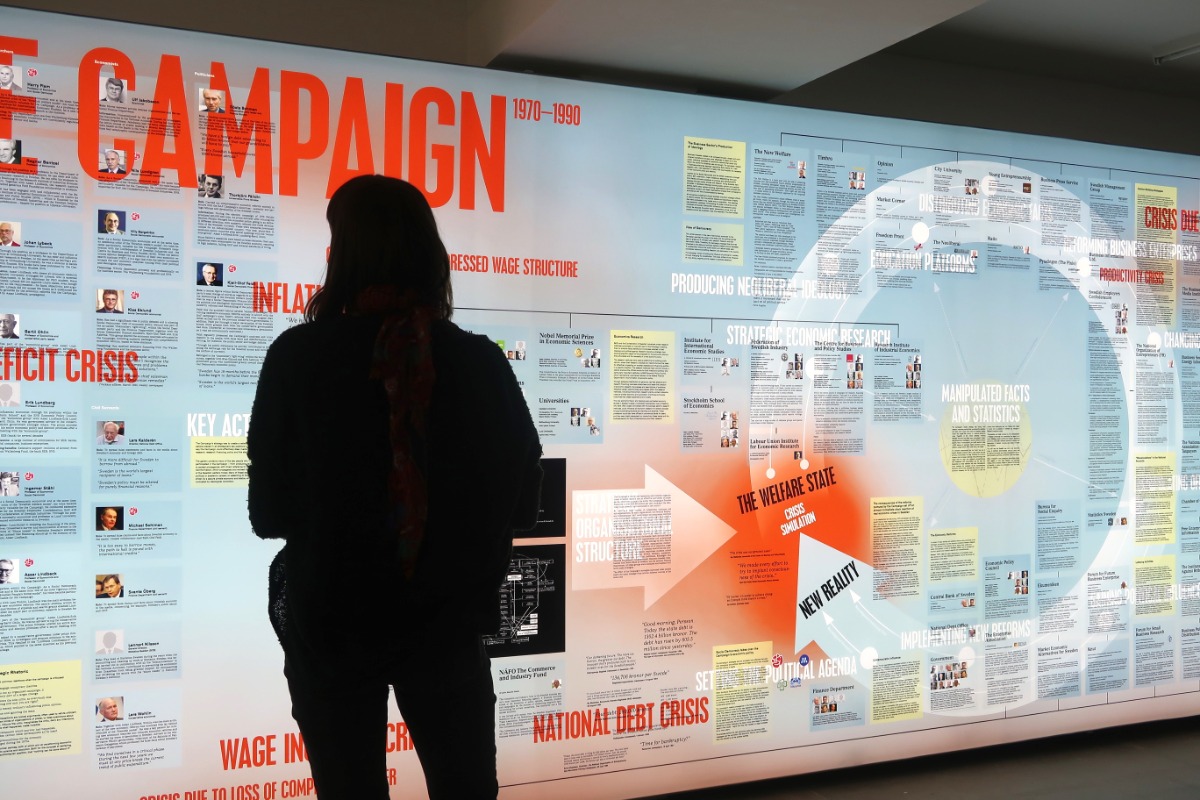

Nathalie Gabrielsson: The Campaign. exhibition view, Index, 2020

But I think it’s not just the situation in Sweden. Around 15 years ago, the world seemed to be moving in a completely different direction. What happened then?

It's a disaster. Every day brings new things that dismantle our ability to envision the future. It’s really difficult to see a hopeful future now, and for younger generations, it's terrible because they can't see a possible future. Twenty, thirty, or forty years ago, you could fight for something with a previsualization that things could be better. Right now, we are creating a world where it's really difficult to be positive.

At the same time, we continue to work, to create, engaging with artistic and cultural practices. However, the whole polarized situation, along with the media's construction of reality, is having a significant impact. You can see this shift in writing as well. What’s the goal when someone writes? Is it to get attention or to discuss ideas? There has been a shift, and I’m pretty sure it's connected to how information is distributed and received and how we react to these changes. The emotional weight has become extreme; ideas seem less important.

The Nordic countries represented a kind of utopian vision – not necessarily a reality, but an important one for the rest of the world. When people considered exile, they often thought about going to the Nordics or to Canada. However, this perception is now in crisis. This specific construction of the Nordic ideal is fading, and the idea of offering alternative ways to understand the world is diminishing as well.

You can see this shift also in political discourse. The desire to help and propose models for improvement is no longer prevalent, which has significant repercussions. It’s difficult to see where we are headed now, and this uncertainty affects not just the art world, but everyone

It's so strange… How did we move from a position of becoming an increasingly open world to one that is closing off, building walls, and experiencing such polarization in society? In your opinion, what do you think was the main force that pushed us in this direction?

Well, that's a big question! I think it's a combination of factors. On one side, the balance of the Cold War meant that for every political project, there was another one on the opposing side. So you couldn't destroy your own political project because there was always another one. However, at this moment, it seems we only have one dominant project: the capitalist project. This entire capitalist framework is rooted in internal fight and competition. What we witness now is a race for winners rather than a focus on social construction.

Additionally, this media construction of reality is making reality invisible. I think it's super interesting – the transformation of reality in platforms, but also on an individual level, like how we construct ourselves as social personas. Because we are projecting fictions and then we transform reality into a narrative.

Right now the simplest narrative is the one that is working, we don't accept complexity in the narrative. Take Elon Musk and similar figures, for example – they embody a narrative that is more akin to a short story than a novel. It's easy to read and easy to follow. In contrast, when we engage with art, we delve into the opposite. We grapple with questions, complexity, and difficulties. We work with languages that are not stable and embrace a flexibility that characterizes a system without rules. However, being in a system without rules is challenging. Because then it's your own responsibility or your own capacity to be critical. It means that it's demanding.

But again, I believe it’s a combination of factors that have led us to where we are today, with the capitalization of politics being one of them. Of course, wars play a significant role as well; they are big business. There’s the moral dimension to consider, along with the increasing polarization and division we see in society. This accelerating machine drives us toward a state of individual uncertainty, which serves as a powerful tool – it leaves us scared and paralyzed at the same time. But, let’s see what happens. At some point, things must change in some way. We need to find alternative methods for addressing these challenges.

Bodies and Antibodies. Exhibition view, Index, 2023-24

But is contemporary art really capable of being a powerful force that can change this situation and stop this race?

I love this question because it's a question about faith. For me, contemporary art specifically, and culture in general, are probably some of the last public arenas where we can think and talk freely. The traditional public spaces now are also organized through economic systems. We see this in the way advertisements populate public spaces and how these spaces are constructed. In contrast, exhibitions and art often follow different pathways. When you enter an exhibition, even if it's indoors, it feels like a public space, and that experience is different. You can define yourself much more as an individual, and the way you behave is less structured than in other contexts.

So, for me, it's a place to reclaim. We have this resource that remains one of the last we have. It requires a lot of faith because we know that art is not easy; it’s not generally accessible since it doesn’t follow a simple narrative. It’s something that is deeply emotional and inherently unstable, constantly in flux.

I love that we can create something in a context that is constantly reconsidering itself, being aware of self-criticism while also exploring the possibilities of defining and discovering new concepts. I am extremely interested in the linguistic and structural aspects of art. We can create a vocabulary and define a grammar that others can use. Together, we can develop a sort of methodological approach to engage with reality that is not the usual one.

At the same time, art can exist in a bubble and function as a self-contained system. So how can we find connections beyond this? How can we remain open to others? Or how can we show that there are no codes to enter this club if it's a club? It's not that simple. At Index, for example, we have our Teen Advisory Board, from which we gain a lot of valuable information. This group of ten young people provides us with insights into how they think, how they view the world, and the problems they perceive within the art world. They are not necessarily connected to art, but they have a cultural curiosity. What we see is that they also seek complexity. But products in general tend to be extremely simplistic. For instance, we can binge-watch series on Netflix, and after investing many hours, we often forget them within a couple of weeks. They don't affect us or transform us in any significant way. In contrast, if you have a fortunate encounter with art, it can change your life, and certain experiences will linger in your memory. I feel super happy when I witness this impact. It doesn’t happen all the time, but when it does, it signifies that the experience has meaning.

How is the art scene in Sweden evolving across different mediums in the visual arts? In what directions is it heading?

There is more emphasis now on research, including artistic research, as artists can receive economic support for pursuing a research project over five years. This means that a series of artists suddenly have significant time to focus on a single question. I think it's interesting, as it helps break the speed and tempo of the usual flow. However, this is context-dependent, as it relies on the availability of resources to enable such endeavors.

It’s also true that the Swedish artistic context has been safe for decades. The same system of support, the same type of market, and the same institutional structures have persisted. For a long time, there were fewer artist-run spaces or alternative proposals. Now, we are seeing more of them, which makes me very happy. These new types of structures don’t necessarily accept the status quo but instead strive to propose other modalities. It’s a slow process, with many things happening behind the scenes, in the “kitchen,” so to speak, making it difficult to observe from the outside. However, this rethinking process is definitely underway.

But speaking about formats, there’s an increasing presence of video, more and more performance and performativity. And for me is interesting this long temporality, there's no need to burn a project and then in two months you start a new one. I see many artists embracing continuity in their work. For me, it’s crucial how institutions engage with artists, not just by producing exhibitions and then moving on, but by fostering a slower tempo that remains open to others. I notice a growing emphasis on process rather than fully defined projects. There’s also a stronger connection with other fields – art and dance or performance are much closer now, as are art and writing. There’s more interaction with other cultural spheres than before, which I see as a positive development. It’s encouraging to see more players actively participating in this evolving dynamic.

Josefin Arnell: Crybaby. Exhibition view, Index 2024

It’s great to hear that. In Riga, I’m part of a group of poets who were gradually transitioning into becoming artists.

At Index, we work a lot with this approach – it’s part of our DNA. The production of text is an artistic process, closely tied to the possibilities of language. Poetry is something both demanding and open at the same time. Reading poetry might seem easy, but it’s not. However, when you find something within it, you gain a lot as a reader because a poem demands your participation. You’re building images and transforming the language into something personal and meaningful. I completely understand these processes, and they make perfect sense. I think we need this in art. We need these kinds of connections to rethink how we work, who we are, and what possibilities lie ahead. Exhibitions are one form of contact, but books are incredible tools, aren’t they? You write a book, and it remains active even 100 years later. I do feel a little envious in that sense because when I create exhibitions, especially temporary ones, they’re open for maybe two months. But once they’re over, they’re gone – you can’t visit them anymore.

But you still have a catalogue.

But it’s not the same experience. I’m actually quite obsessed with this idea—finding other ways to do exhibitions that have different temporalities.

And what about technology? Is it changing the whole picture of what’s happening in art, especially in Sweden and the Nordic context? I remember 10 years ago, everyone was talking about virtual reality, like these helmets, and it seemed like in 10 years everything would be VR. But that’s not how it’s going. It’s not going so straight in that direction.

We’re at a point where many people think that if art isn’t working with technology, it’s not contemporary. For me, one of the strengths of art is that it allows you to step back and observe things critically. But technology has always been present in art. It’s interesting to look at how technology was used in the past, like in the ‘90s. Technology has always been a factor. We remember how net art emerged, promising to change everything, but then nothing really happened. Technologies are often tied to specific moments, and they have a short-lived temporality. For example, I remember the birth of video technology. It was a revolution, but we're still living with it today. You can film for hours and hours, and video is now so embedded in our reality that we no longer see it as a technological tool – it’s just part of the landscape. But with VR, it's still something that needs to be defined. We’re not there yet. It’s hard to envision VR in a public context because it's an individual experience. Many artists are working with it, but how do you present it? You can’t create a communal space for it the same way you would for other mediums. Maybe it’s not even necessary to do so. People can experience it at home, and in that case, institutions and assistance around it may not be required. Let’s see where it goes.

But I’m also really interested in ideas of veracity and what happens with technology and AI. It leads us to the question: what is the idea of truth in art? Because art has this unique power. You see something, and you believe what you see. I don’t know why, but there’s this idea that an artist is always telling the truth.

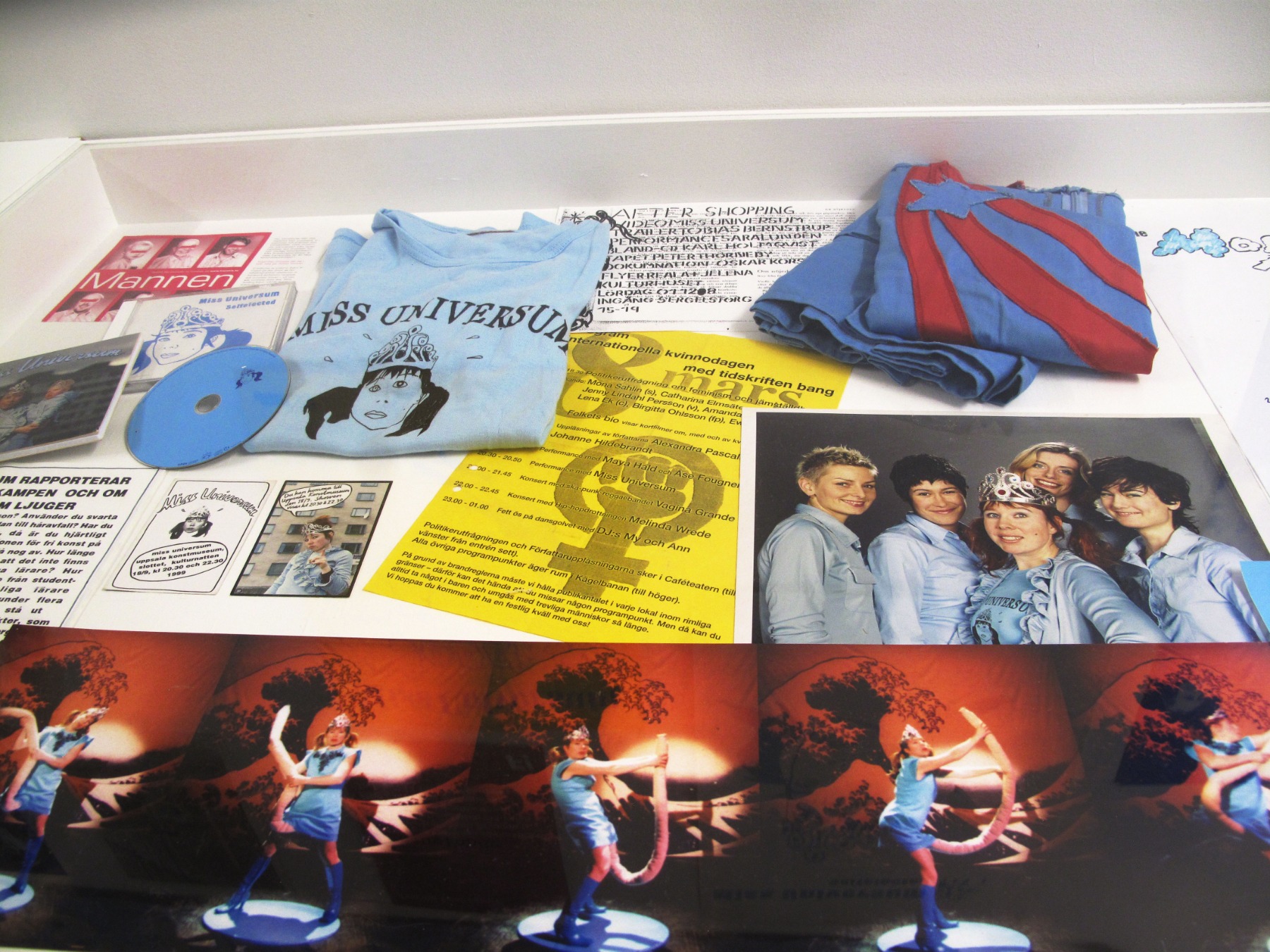

Catti Brandelius: Miss Universum 1997-2005 (2023). Exhibition view, Index 2023

Directly from his heart!

Yes! We really believe in this idea, and I’m not entirely sure why, because artists can lie too. But as a visitor, as a viewer, there’s this empathic connection with the artist, because it’s this person who’s somehow bringing everything to you. We know there are many narratives, ways of dealing with, constructing, and fictionalizing these things. But what happens when there’s mediation through a type of technology that’s still not fully defined and has to find its own path? Some technologies become outdated very quickly, while others stay with us and become part of our lives. And I’m not sure which one will be the one to stay.

You were saying earlier that we are living in a model of competition, but do you think the situation with AI is making this competition, which already exists in the art world, even stronger in a way?

I think that AI, as a tool, is interesting, but it’s still not evolved enough to create on its own. It’s always relying on references. We are feeding the machine with references, and then the machine gives us another type of result. Yeah, it can be interesting, but I’m more interested in the structure around it, more than specific examples. What does it mean? How does this thing change our way of looking, defining, writing, or creating? If it’s just a tool, that’s fine – we’ve always worked with tools. But if we start giving the responsibility to the tool itself, the result will be extremely limited.

This machine is offering you a type of grammar, a system of thinking. It can’t work outside of that system. I really love the work of a British artist, Anna Barham. She has been working a lot with software, especially older versions that aren’t as advanced as the latest ones. She explores the mistakes of the software, like voice recognition or text transcription. For example, if you take a conversation like this one, it’s super easy to transcribe things now, and it’s quite precise. But just two years ago, it wasn’t precise at all. What Anna Barham did was read these mistakes as poetry — all the errors that the machine made. She embraced these mistakes, put them back in, and layered them. The result is really beautiful because it shows a distrust in the machine. We should consider this, because while the machine can seem intelligent, it will also make mistakes.

In politics, the use of technology is leading to increased polarization and a simplified construction of the world. At the same time, it's paradoxical because while machines are much more advanced and could accomplish far more, the type of content they produce is limited to superfast consumption. This is meme culture: it’s created and consumed in the moment, with no intent to last forever. A meme is made to exist now, and within minutes, it fades away, and that’s fine. But in art and writing, there is a longer-term desire for persistence. This is something we need to reclaim, to emphasize its importance, because this is what will remain in the future. So, how can we find other strategies, other systems, and ways of thinking that can also impact a potential future? If there is a future, of course, let’s hope.

Catti Brandelius: Miss Universum 1997-2005 (2023). Exhibition view, Index 2023

But how do you perceive people who are working with AI in this artistic way, creating pictures? Do you see them as artists, actually? Because, I mean, they cannot draw. They cannot, you know, make a picture with their hands.

The machine, the tools, need a brain. The question is – what kind of brain is there? Whether it's an industrial brain or a human brain isn't that important. But all conceptual art is based on other people doing the practices as well. So the fact that an artist is using technology to create artwork isn't the most relevant point. For me, the focus is on the idea, the process, and the intention to offer something meaningful. If it's a machine creating the work, that's fine. But I expect more than just a surface-level result because it's a machine. I always expect the criticality that comes with the artistic perspective.

And of course, AI has its own aesthetics. Whether it's conscious or not, there's a type of production that is related to the world, because the sources of information are rooted in reality. It will be interesting to explore. But again, looking at the classics, I go back to Salvador Dali. He was experimenting with technology, holograms, and machines to create things, but always with an underlying idea. We could even go back to the Renaissance and the studio systems, where artists had a team around them to help produce the work. So, we’re not that far off. It’s not that we’ve changed everything. We’re still operating within the same system. What’s different now is the super-fast pace of production, which is largely out of our hands. We’ve handed it over to machines that do it for us. But it was the same with computers in the past, and before that, the typewriter. So, in a way, we’re not that different now.

What we see is something that is extremely spectacular and spectacular in all the senses. It’s about creating and defining surfaces that are polished and brilliant. But is that all there is to it? I really appreciate this critical approach to technology – taking a step back and saying, 'Wait a minute.' Because if these machines are learning, what exactly are they learning, and from which context? What happens when we consider the existing societal problems? Are they learning to be racist? Are they learning to be classist or homophobic? The reality is that they are, because there are no limits. They are simply gathering information and transforming it according to patterns, without questioning the biases embedded in the data.

There’s a researcher, Carmen Leal Hines, who has been studying the use of artificial intelligence in the porn industry. It's one of the fields where AI has advanced rapidly, particularly in terms of economics. The difficulty lies in how brutal it is because it often reflects the most brutal aspects of society. This happens because AI is driven by demand – algorithms keep offering more and more, pushing toward the extreme. In the end, this leads to a disaster. I think it’s interesting to observe these processes, where machines are not neutral. They are shaped by the context in which they are used, which is a crucial insight.

What’s interesting about art is that it allows us to turn the machine around, or to observe it in a new way. And when we do that, something new can emerge. However, we still need extra time to fully understand how this plays out. In many ways, art is a conservative system. When something new happens, it takes a step back and observes, saying, 'Let's wait and see.' This is not necessarily a bad position to take – it’s actually quite thoughtful.

The results of using technology in art are still up for debate. I’m not sure if we’ve seen truly groundbreaking results yet. But I can certainly see some artists doing brilliant things, using technology to create new worlds and experiences. This tells me that technology is an extra tool, a new medium, but not so different from others we’ve used in the past.

Project Zone, Art Vilnius 2024. Photo: Art Vilnius/Andrej Vasilenko

I see. But you're here in Vilnius – is this your first step into the Baltic art context, or do you already have some experience with it?

Yeah, I've been observing, and we're not that far physically. It's nice to see the connections. We’ve also been working with artists from here and the region. There's a really interesting history here, and I can personally relate to it — processes of change, the definition of national identities, and what's happening now. What has happened, and where are we right now?

We're in a strange moment of concentration, where everything seems to happen in its own bubble. Right now, more than ever, we need to be connected, to seek new observations, and to explore different ways of dealing with reality, construction, or whatever else. It's important to be open, to read, and to listen to other contexts. So, yeah, I'm happy to be here.

Upper image: Nathalie Gabrielsson: The Campaign. exhibition view, Index, 2020