When 10 Artists Meet 10 Writers

The 9th Artishok Biennial in Tallinn is taking place until 20th of April. Why is this edition special? We explored this question with its curators, Brigit Arop and Margit Säde

Last held in 2022, the 2025 edition of the major contemporary art biennial, with curators Brigit Arop and Margit Säde, is titled Siesta. The openings of ten new artworks will be taking place sporadically throughout February and March at various locations throughout Tallinn. For the first time, the opening ‘marathon’ of the biennial is truly a marathon, and not a sprint like in previous years. Namely, the openings are taking place throughout the two months of the festival, thereby allowing for a much-needed breather, or as the title of the biennial suggests, a ‘siesta’ amidst the hustle and bustle of the openings, and one which everyone – organisers, participants, and the audience – can take advantage of.

Furthermore, this year’s biennial will take place at various venues in the public space of Tallinn, often activating locations that are undergoing transitions or are stuck in an in-between state. Making good use of the unattractive time of year, as well as the low season and human hibernation, the works will be presented in places that do not usually exhibit art.

At a time when the interpretation of art – including various attempts at analysing and ‘decoding’ it – are becoming increasingly relevant in the effort to undermine accusations of contemporary art being inaccessible and elitist, the Artishok Biennial seems more relevant than ever. Here, the creation of art and its interpretation go hand in hand throughout the entire two-month duration of the biennial. I spoke with the festival’s curators, Brigit Arop and Margit Säde, to learn more about this interaction between artists and writers.

Artjom Astrov’s work JUICE is open at Vanaturu kael 3. Photo: Joosep Kivimäe

Could you start out with a few words about the background and concept of the Artishok Biennial?

Margit Säde: This year the Artishok Biennial (AB) is taking place for the ninth time. It was first held in 2008 and was initiated by Maarin Ektermann and Margus Tamm. The main reason for creating this Biennial, I believe, was to revitalise the local art scene and art writing. What makes it particularly special is that it allows 10 artists to create new works, resulting in 10 entirely new pieces. Additionally, 10 writers provide commentary on each of these works. So for almost two decades, the AB has locally fostered and supported both the creation of new works and writing about art. It has taken place in various locations, including once in Riga. I only found this out when we started working on it.

In Riga? What year was that?

Brigit Arop: In 2014, the Artishok Biennial (AB), titled 'A+B=AB14,' took place at the Mūkusala Art Salon in Riga. This was the first time the AB was held outside Estonia. Half of the artists and writers were from Estonia, and the other half were from Latvia.

What is coded into AB’s DNA is its structure: it always brings together 10 artists, 10 writers, and spans 10 opening days. This format has remained unchanged since the beginning. Each edition is passed on to new curators, who have the freedom to shape it as they wish – choosing the location, the theme, the artists, and so on. We aimed to reflect on the initial goals of Artishok, while also recognising that it no longer needed to serve as a revitaliser or energiser of the art field, as the scene had already become vibrant. Instead, we sought to adapt the format in a way that was feasible for us, which led to the creation of the ‘siesta’ concept.

M.S.: We were intending to kind of slow it down, stretch it out. Because actually, as Brigit said, this 10-day marathon that Artishok was normally based on was not only intense for the curators and participants, but also for the audience. So we wanted to try and slow things down, focus on working with locally based artists and writers, and to rethink the format that we were given. This year we divided the Biennial into two parts – the first one runs from from 20 to 28 February with four openings, then there is a two-week break – a ‘siesta’. And then from 15 to 28 March, we continue with the last six openings.

The opening of Lieven Lahaye’s work “[…] kept in private, Making it public” in the A. Laikmaa tunnel. Photo: Joosep Kivimäe

It's very interesting that it's an event that not only celebrates art, but also interprets art. As I understand, the new texts which are created for the Biennial are not exactly the usual kinds of art criticism one sees. It looks like a very diversified approach to art as an object of description or interpretation. How do you view these ways of writing about art which can be seen at AB?

B.A.: The format of creating new works and then writing about them sometimes sets very strict limitations. One of the biggest challenges is the timeframe, which can be difficult to manage. We wanted to ensure that the works were actually ready by the time the writers began writing about them. However, this hasn’t always been the case. At times, writers have had to be very creative, as they might only see a fragment of a work or a representation of a piece that is yet to be installed. Despite this, the texts have always been imaginative. I remember one writer who attempted to represent each work in a single sentence.

Ultimately, the writing process is shaped by each writer’s personal interests, approach, and inspiration. This time, for example, one writer is posing questions to the artists, while several others have approached their writing as letter-writing. There's even an artist who records her dreams as inspired by the siesta concept. So, yes, the process is always very open and free.

M.S.: The AB isn’t about writing classical art reviews; rather, it’s about writing as something else – perhaps even as an art form in itself, an experimental art writing that explores all possible approaches. It is a very exciting and generous situation for the artist, to have such a variety of texts engaging with their work from different perspectives and styles. The writers we have invited come from very diverse backgrounds – while some are art historians, others are translators, journalists, screenwriters, or simply artists who also enjoy writing. We intentionally mixed the group to include a broad range of voices.

B.A.: I think the idea was also to explore what art writing could be.

M.S.: Yes, exactly, and here, there are no wrong answers to this question.

So there are no restrictions or rules as to how they should write?

B.A.: Just the limitation of one page.

And what about the places where these art pieces are exhibited? Is it always 10 different locations, or can a few works be displayed in one place? How does that work?

M.S.: Each work has its own location. The Artishok Biennial has been spread out across the city before, but often there’s just one central location where both the works and texts come together. For example, the last edition was held at the Tallinn Botanic Garden.

This time, as curators, we were particularly interested in working in the public space and finding artists who were willing to do the same. Some works are outside, in the city, without a specific room to host them. Others have found locations that support the work's theme. For instance, one work is displayed in the old kiosk in the Central Market, which is not in use during the winter season. It’s a fascinating place, as Tallinn is changing rapidly and the market is set to be torn down soon. Another work, by Artjom Astrov, is located in a basement in the Old Town. This commercial space is difficult to lease out due to the high rent. So, yes, each work has its own location, and the location is chosen to complement the work’s specificity.

The first presentation of Alana Proosa’s video journey "Pivotal Points". Photo: Joosep Kivimäe

Could you say a few words about the first few works that have already opened, or ones that will be opening in the upcoming days?

B.A.: For example, on 25 February we had our third opening with a work by Alana Proosa. Her background is photography, but she’s also been involved in punk bands and has done performance art. However, she hasn’t exhibited in many years, so we invited her to participate. Her work takes place over five occasions throughout the Biennial, at which time she gives a guided tour through the city while talking about inline skating. At the same time, she projects a video she has created onto various surfaces of the city and its buildings.

M.S.: A work that opened on 28 February is a site-specific installation by Anu Juurak called Lift. Experiment. Anu works at the Tallinn University of Technology, where she has 'hacked' an elevator in one of the school’s buildings. This will be an indoor installation that is accessible during the opening hours of the university’s School of Business and Governance building.

The opening of a site-specific installation by Anu Juurak called "Lift. Experiment". Photo: Kaur Tõra.

Photo: Kaur Tõra

Did she really hack the elevator?

M.S.: No; when I say 'hacked,' I mean she altered the environment inside the elevator. The elevator still functions as an elevator. Basically, she covered all the panels – including the ceiling and the floor – with mirrors. This creates a disorienting effect, making it difficult to tell which direction the elevator is moving when you step inside. It’s a perceptual experience.

The concert by Kisling and Artjom Astrov. Photo: Joosep Kivimäe

I understand the first opening was a video work by Artjom Astrov.

B.A.: It’s more of an environment where videos take centre stage, I think. He doesn’t want to say it's just a video work, though – it’s also the sound and the room itself that create a kind of landscape or space. It's a place where you can come, watch the videos, listen to the sound work, and simply hang out.

M.S.: He mentioned that he was trying to create a space that encourages people to come together informally. Someone asked, 'Together, only together?' and he responded, 'No, you can also be alone, but also informally.' That’s why it also has slightly different opening times compared to a typical gallery. For example, on Fridays and Saturdays, it’s open until 10 p.m. Artjom wanted to emphasise the idea that after work, or whenever you pass by, you can stop in and spend some time, and not just as a viewer of an exhibition, but as part of the environment itself.

At the opening there was also a concert by Kisling and Artjom Astrov, and it worked really well in this space. Due to the fact that it's not like a club or a gallery that people know, it had a kind of out-of-place feeling. You're in Tallinn, but at the same, time you're not really sure where you are. It reminded me of the end of 1990s or something, when we had more of these spaces where people could informally come together...but now there are fewer and fewer of these kinds of places available.

The opening of Lieven Lahaye’s work “[…] kept in private, Making it public” in the A. Laikmaa tunnel. Photo: Joosep Kivimäe

One work opened just recently...

B.A.: Yes, it's a work by Lieven Lahaye, and he’s making a publication about cataloging and archiving. His background is that of a librarian, and for the AB he wrote three new texts and published a new issue of Catalog (with Ott Metusala as the designer); he’s exhibiting it at a former underground kiosk.

The location is quite significant because it’s right beneath Viru Keskus, which is our main shopping mall – one of the earliest ones as well. The urban space around it has changed a lot in the last couple of years as new tram lines are being built, among other changes. Previously, people used the tunnel a lot because there were no crosswalks at street-level. However, Tallinn is now rethinking its urban space, and new crosswalks have been built so that pedestrians no longer need to go underground. As a result, the rental space where the kiosk used to be has been empty for several years.

Lieven is interested in these in-between spaces, as well as in waiting and archiving. The three texts in the exhibition explore concepts of hanging out, queuing, and the state of perpetual waiting. There are also hidden visual objects that you can find by peeking through the posters on the windows. Additionally, there’s a sound work in which he reads the texts aloud.

M.S.: This is a space you can't enter, but you observe it from the outside. Through the windows, you can peek in and see the posters, the text, hear the sound, and notice little elements that he has added – small hints to make the space more lively.

Photo: Joosep Kivimäe

The new texts, which are interpretations of the artworks, are they also exhibited in these places alongside the objects, or do they only exist online?

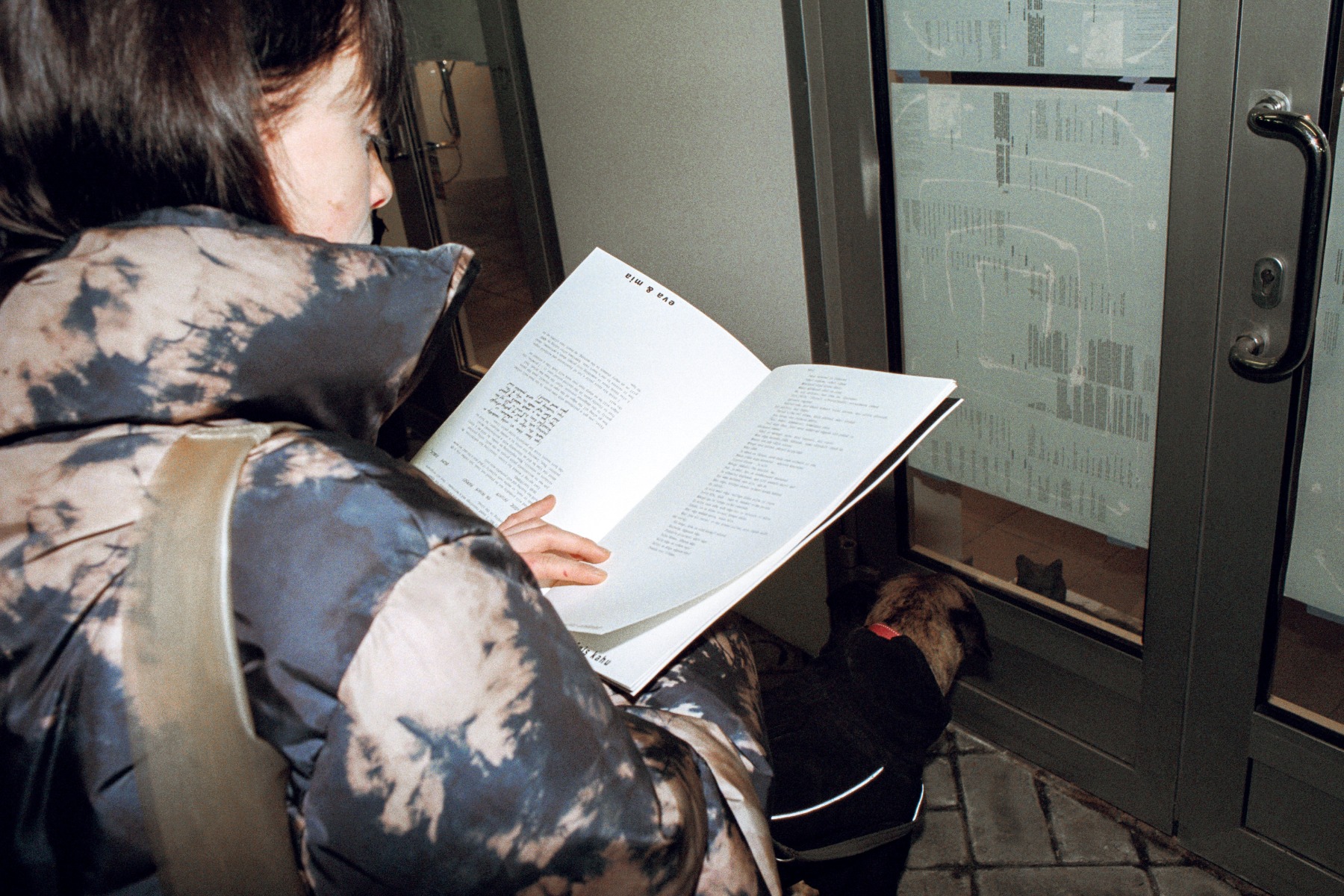

M.S.: Yes, we have them on the web, but they don't appear all at once. We publish them in the same order as the new locations open. Additionally, we also have a printed publication. The text is available in both English and Estonian, and the publications will be available at the locations where the works are displayed.

But the writers have done their thing quite a bit before the official opening, right?

M.S.: The artists have presented to the writers the ideas behind the works as well as shown parts of them beforehand. So, the writers hadn’t actually experienced the works in the locations where they will be exhibited – they saw the videos, they heard the texts, and they were informed of the locations. But they still had to do a lot of imagining while writing.

That’s interesting. So it's half reality, half imagination.

M.S.: Yes! But I guess that’s what art writing often is – there’s always an element of play or chance. We all experience different details of the work or emphasise different aspects. I wrote for the 7th Artishok Biennial in 2020, and I know it’s rather challenging to write this way. When the artist's intentions are clearer, and if you’re familiar with their work, you can follow the lines and imagine the work more easily. But if you’re less familiar with the artist’s work, it can be more difficult to write in this way.

The idea is really to publish the artwork and the text at the same moment, so the texts also have their own opening moment. Normally, texts don’t have this celebratory moment when an exhibition opens, but with this format, the texts are published at the same time. It’s challenging, but that’s what makes it exciting. For the artists, it’s really nice to have so many different viewpoints, because in a typical local scene, you rarely get such diverse reviews or feedback in such a luxurious way.

Photo: Kaur Tõra.

I see. And my last question: Does the selection of various locations in public spaces around the city help attract a new audience?

M.S.: Yes, definitely. That’s what we hope for. Of course, there’s a chance that people might just stumble upon the artworks – there are people who go to the market anyway and will see the work exhibited there. Or there's this empty lot between the houses that people pass by when heading to the bus station, and we have a work there. As curators, we were interested in creating these situations where people can unexpectedly come across the works, even if they don’t know anything about Artishok. Some of the locations might be a little more obscure than others, but we’ve specifically worked with signage to grab people’s attention. So we’re hoping to attract people who might not normally visit art exhibitions or art galleries.

Upper image: Brigit Arop and Margit Säde. Photo: Joosep Kivimäe