Contemporary Art as a Form of Thinking

The Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art (LCCA) turns 25! What does Solvita Krese, who has been the director of the centre throughout this long and eventful period, think about this momentous milestone?

The LCCA is an amazing art institution. The term ‘contemporary art centre’ usually means a specific space where exhibitions are held and where the activities of such an institution take place. Although the LCCA has an administrative office on Alberta iela, its exhibition space is basically the whole of Riga – all kinds of buildings and places, including markets, closed-down factories, libraries, university departments, simply empty buildings, and even museums (of art as well as other subjects). This rather unique approach allows the centre’s network of contacts and its audience to continuously expand. And in this case, it is also reflected in the way the team and friends of the centre are preparing to celebrate its anniversary. According to the centre’s website, ‘the nomadic nature of the organisation has inspired the format of the 25th anniversary celebrations, encouraging us to see the LCCA as a living organism – a mycelium – whose threads of activity and influence spread through walks led by artists, writers, poets, philosophers, researchers and curators, collectively creating a cultural map of the urban environment’.

Solvita Krese, who has been the director of the centre for all these years, is a person whose energy, stamina and dynamism of thinking can only be envied. On a sunny May day in her office on Alberta iela, we spoke about how and why the centre came into being, what purposes it has served over various time periods, what she thinks of the centre’s current situation, and her predictions for the future. We also covered the upcoming anniversary programme – a 24-hour event starting on the morning of July 31.

Solvita Krese, Survival Kit 15, 2024. Photo: Didzis Grodzs

If you had the chance to go back to the year 2000, what would you do differently?

A couple of big events took place in my life in 2000: I had a baby, and I founded an art centre. Now my son is 25 years old, the same age as the LCCA – they are a whole different generation unto themselves. He’s at something of a crossroads in his life at the moment. As a young person, he wants to decide what he’s going to do in life, but because he seems to be good at everything, one single path hasn’t really come into focus. We were recently taking and he said, ‘How I envy you – you knew straight away what you wanted to do in life’. In that sense, I really think I am a lucky person. Very, very early on it was very, very clear to me that I wanted to ‘do art’. At first, I wanted to be an artist – but that didn’t work out (which was probably a blessing in disguise). I feel that the path I am on now is the right one. Taking the initiative to continue the work of the Soros Contemporary Art Centre (SCAC) was the right decision, although probably a rather bold one at the time.

I don’t think I would have done anything differently. When the SCAC came to an end because George Soros had decided to discontinue funding these initiatives – more than 20 art centres that had been set up in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet countries – there were two options. One was to simply liquidate everything, close it down. The other was to try to continue with the start-up funding offered by Soros. The then director of the centre, Jānis Borgs, said: ‘That’s it, then – let’s close it down’. But that seemed so wrong; there was so much work, so much investment, so many resources here.

And so, with relatively little experience, I took the initiative – this work should be continued and developed. Looking back at the work of the art centre and the many projects we’ve brought to fruition, it’s clear that many of my decisions were taken in response to specific situations. I simply could not have done otherwise. I had not been planning for years on how to establish an institution. I just had to act in the moment – here and now; if I didn’t take the opportunity then, there would simply be no other opportunity.

Bolderaja procession, 2002. Photo: Valts Kleins

The Survival Kit art festival also came about as a response – as a reaction to a crisis situation.

It was a response to the ‘emptiness’ of the economic crisis – the empty shops, the lack of funding, the mood of society at the time. You can’t just not react to it. You realise that this is a situation where you have to do something – you can’t just sit there with your hands folded in your lap.

And that’s how Survival Kit began. Artists occupied these empty spaces, filling them with creative energy. And for very little money. Nobody thought it would evolve into a festival – it was a spontaneous, almost impulsive response to the situation.

And ever since, we’ve kept asking ourselves: does it still make sense to have a festival under this name? And every time, the world brings us new themes and new crises. In fact, today we have to talk about survival more than ever.

I think that reacting to the situation – spontaneity based on rational action – is probably my best format.

Opening event of the Survival Kit 15, 2024. Photo: Sandra Garanča

Back in 2000, what did you see as the centre’s mission – its reason for being? Has it changed over time?

It has changed several times. In the beginning, the centre was set up as a Public-Private Partnership (PPP) – a joint collaboration between the state, the municipality, and the Soros Foundation. One of the tasks of this institution was to fulfil, in some manner, the functions of the state and also the functions of the municipality, because they were our founders. The creation of a museum of contemporary art was one of the leitmotifs to be developed. In the beginning, cooperation with the state was quite close because they provided part of our funding, and we fulfilled a number of functions delegated by the state. But then the governmental powers that be changed and contemporary art was deemed to be of little importance. That was also when Latvia stopped participating in the Venice Biennale.

When was that?

In 2003; Latvia was supposed to be represented at the Venice Biennale by ‘The Famous Five’. Māra Traumane was the curator, and the project had already been included in the main Venice catalogue with a description and a picture. But the Ministry of Culture suddenly decided that there was no need for such a thing, and simply pulled the plug. Concurrently, it was announced that the Ministry had no interest in supporting an initiative such as the Centre for Contemporary Art. The Ministry of Culture withdrew from the circle of founders, and after a while – linked to the legal reform going on – the Riga City Council also withdrew its participation. The only one of the original partners that remained was the successor of the Soros Foundation, the ‘Dots’ [Latvian for ‘given’ – Ed.] Foundation, which is still one of our founders and members.

At that point we became fully independent and autonomous. We started to set our own priorities and direction in a very focused way. If you look at the Latvian art scene – or more broadly, the cultural scene – you can see that our niche has been clearly defined: we are interested in artistic processes that resonate with social and political events. At the moment, we are focusing on ecology, the building of an inclusive society, decolonisation, and other topics that affect society outside the field of art. This is also how we see our mission – art as a catalyst and stimulus for larger processes.

Looking back on 25 years, it is safe to say that we have been able to influence various processes – both in the perception of art and in communication with society. We have been dealing with decolonisation issues for some time now, and this topic is also becoming increasingly relevant in a global geopolitical context. We started talking about it around seven years ago. Art is a very powerful tool with which to talk about these things.

Survival Kit 10 (2018)

But if you look at what is happening in the part of the world that is united by democratic principles... So much has been invested in a direction that is socio-politically inclusive and tolerance-based, but almost everywhere now there’s been a turn towards conservatism and narrow-mindedness. Isn’t that somehow... painful?

It is not just painful – it is truly tragic. I think that both I and a large part of society – including ourselves, i.e. artists and art institutions – had no idea how fragile this world we had built over many decades really is. It seemed to be a solid edifice, gradually strengthening and cementing itself with values of equality, inclusion and others that we had taken for granted. And now it all seems to be simply...exploding.

On the other hand, looking at the broader context of history, we see that the world cyclically undergoes changes. Like the pendulum of a clock, it goes one way, and then it comes back. I just don’t know how far it will swing the other way now. And then there’s that feeling – why do we have to be the ones experiencing this stage, when the pendulum is swinging backwards? Those of a more conservative mindset are likely saying, ‘Finally, the world is starting to sort itself out!’ [laughs] – it all depends on which way you look at things...

I think the most important skill to have at the moment is to not panic or act tragically but to try to see something positive and perhaps try to find some tricky way to turn the ‘mechanism’ back round in some way.

In Latvia, this turn is perhaps not yet being felt as sharply since conservative thinking has historically been quite strong here. I recently spoke to a curator from Spain who has been working in Sweden for fifteen years now, and he told me that in Sweden, there’s a radically conservative party that is calling for zero funding for contemporary art. There are no such initiatives here at the moment.

Yes, but if you look at what might happen in the next elections, for example, in the Riga City Council... I think that conservative values are perhaps not yet being articulated so loudly at the moment. Of course, there is no shortage of such people. But for the time being, liberal, democratic and critical thinkers are still in the majority. Yet the balance of these forces can change very quickly. I think there are quite a lot of people in Latvia who are sympathetic both to Trump’s ideology and to the rise of conservatism in general. There’s a sense that a ‘wave of change’ is coming. We shall see.

And how has the relationship between the LCCA and other art institutions in Latvia developed over these 25 years?

I think that one of the great benefits is that more than 15 years ago, we established the Latvian Association of Contemporary Culture Non-Governmental Organisations (LACCNGO), and the LCCA is one of its founders.

An interesting feature of Latvia is that this segment of contemporary culture is more driven by the non-governmental sector. That’s where this solidarity lies; to a very large extent, we are fighting for common interests. In terms of values and an understanding of artistic expression, we’ve found that the most like-minded institution for us has been the New Theatre Institute. But in general, we collaborate with many institutions because we have chosen this nomadic way of working in which we are mostly involved in creating content and then finding specific spaces or empty buildings for that content. If we are, for example, doing a research-based exhibition with museum works, then we approach the Latvian National Museum of Art (LNMA). If, on the other hand, we are doing an exhibition on dementia or depression, we approach the Medical History Museum. Without being limited by the parameters of a space, we can hold exhibitions anywhere, and we’ve had long-standing collaborations with many institutions – for example, we’ve been working with the LNMA for years.

Exhibition "Unexpected Encounters" at the Arsenāls Exhibition Hall, 2019. Photo: Kristīne Madjare

Was this principle of finding conceptual spaces for each exhibition clear to you from the very beginning?

It was not at all clear from the start how things would turn out. As I said, one of our founders was the Ministry of Culture, and one of its goals was to pave the way for the Museum of Contemporary Art. Initially, we thought that we should have an exhibition space where we could develop our projects. But starting with our first exhibition – Contemporary Utopia, which took place in 2001 at the Arsenāls Exhibition Hall – we realised that we would probably continue to work with large exhibitions based on discursive research, and not just on visual expression. It also soon became clear that we could not sustain such a large space on our own. It’s no secret that there is a serious lack of exhibition space in Latvia.

For a while, we tried to operate a large exhibition space in Andrejsala. Only now, looking back, do we realise how typical this was of gentrification. It was clear even then that eventually, ownership of the space would change and it would be used for other purposes. This is a widespread phenomenon in the world – artists are allowed into empty spaces which they then occupy, give life to, and then they are taken over by others. You know where the Spirits & Wine liquor store is today? That used to be our exhibition space. We also had an upstairs showroom, Ēdnīca [Latvian for ‘eatery’ – Ed.], which we ran for three years with quite an extensive programme of exhibitions. And now, in the context of our anniversary, one of the exhibitions will be linked to this experience.

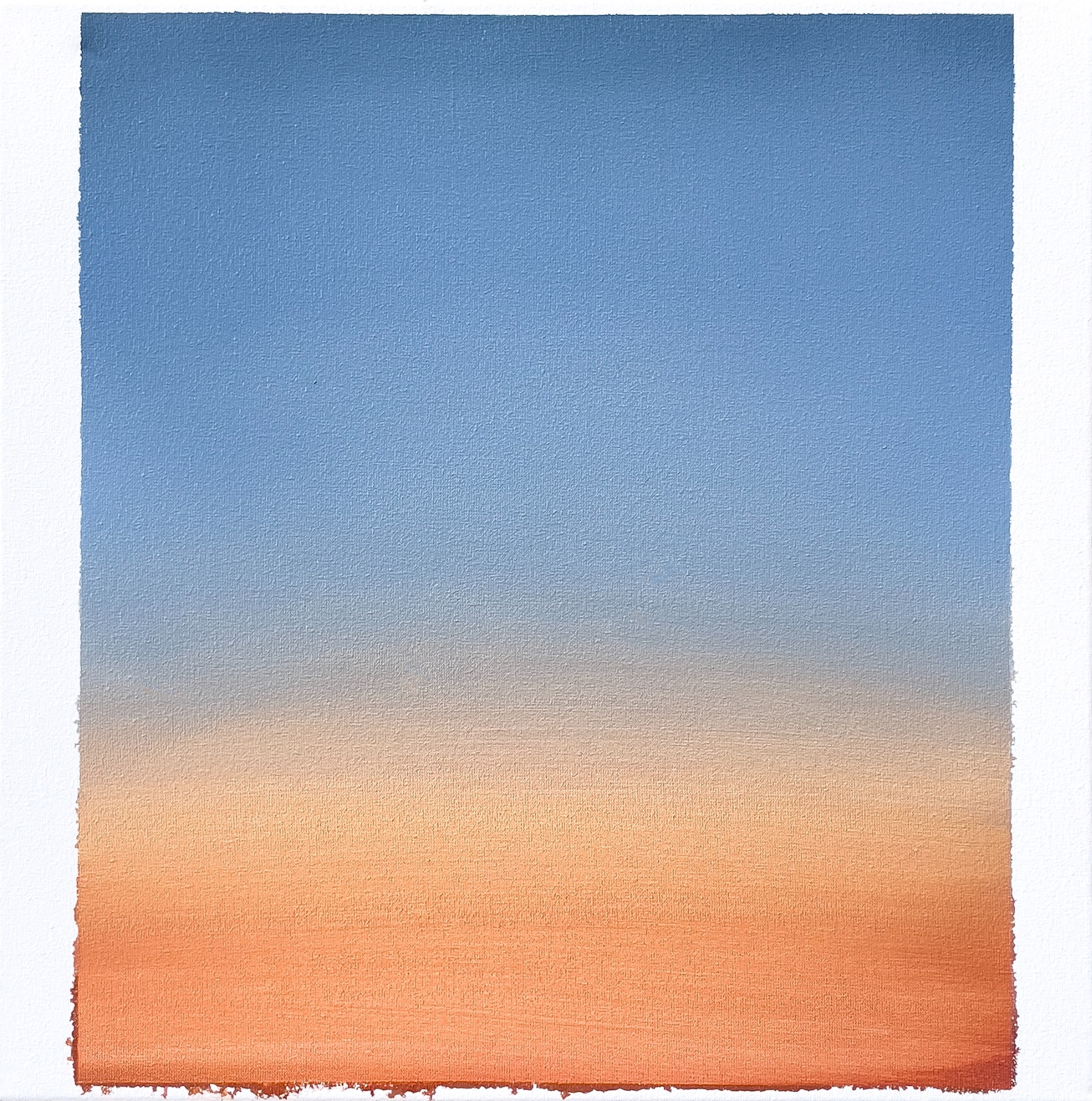

Andris Eglītis, Still under the sky, 2025. Publicity photo of the exhibition

Yes, Andris Eglītis will have an exhibition in the exact same place where it was held in 2005. Back then, the title of the exhibition was Under the Sky, but now it will be the light is sweating. Still Under the Sky. Will the content be similar?

The content will be quite similar – the exhibition will feature several paintings from the artist’s first exhibition. They are large-scale works that were exhibited in a very unusual way for that time – in the dark, on scaffolding, with focused lighting or spotlights. Now they will be exhibited in natural light, and with brand new paintings forming the centrepiece of the exhibition. Once again, the paintings will feature the sky – the same sky, but from a different perspective and as seen from a different place.

Eglītis spent the winter months in the Philosophers Residence apartment complex, where he had rented a studio. Every morning he would go out onto the balcony at sunrise and paint the sky, whether it was grey, overcast or clear. And so a new series of paintings was created – portraits of the sky.

Total body workout performance

I understand the anniversary will start off with dancing?

We pondered that for a long time – how should we celebrate our anniversary?

Last summer we spent many an evening around my backyard fire pit with former colleagues –who have become a large creative community over these 25 years. We sat, talked and looked for the most appropriate format for the celebrations. We came to the realisation that it has to be done through nomadic movement – through walking, through going from one place to another...like a mycelium that spreads imperceptibly but leaves a trace...we have also left our imprint in various places around Riga. That is why the anniversary celebrations will be a series of walks that will take place throughout the year.

We will highlight the themes we have worked on and the places where our exhibitions and events have taken place. These walks will allow us to look both backwards and forwards – to reconstruct events but also to create something new with young artists. It will start on May 31, when we will move through Riga to the places where we have made exhibitions or where our events have taken place. I myself start my morning with exercise, so I thought – why, of course – the anniversary walk could also start with a morning exercise. We will reconstruct Kristīne Kursiša’s Total Body Workout, which took place in 2002 at the Nams 99 hotel located on the far end of Stabu iela. The work had been a part of the 6th Element exhibition, which already had a strong feminist orientation. We did the project together with Katrīna Neiburga, Monika Pormale, and other artists. Back then, both artists and other creative people were involved in the performance – we all did a kind of aerobic performance together. Now, 25 years later, we will do it again. Hopefully, all the performers from back then will be able to take part once again. This time, however, the performance will be created together with the young choreographer Ramona Levane, who has created new choreography inspired by the 2002 event and the zeitgeist of the time. Now we are inviting not only the artists we have worked with over these 25 years, but also new artists and people with whom we have collaborated on a wide variety of projects. We will start the morning with a dance in the lobby of the National Library. We’ve worked in the National Library before – several of our exhibitions have taken place there, including one dedicated to Hardijs Lediņš.

And then we’ll move on – we’ll have a procession with ‘The Countesses’, young artists who are creating this procession with attractive elements. Over the course of the procession we will move towards the Art Academy of Latvia, which has always been a good and reliable partner for us. In the Art Academy’s garden we will reconstruct the performance Leiputrija [a reference to ‘a land of milk and honey’ from a Latvian fairy tale – Ed.], which was part of the first Survival Kit and created by Katrīna Neiburga together with Agnese Krivade. Back then, they invited a number of artists, writers and poets to participate in a creative ritual – cooking a pot of soup together. The activity became an expression of art, togetherness, and symbolic sharing. This time, Katrīna and Agnese will again involve the participants of the original performance as well as new ones – philosophers from the magazine Tvērums [Latvian for ‘grasp’ – Ed.], who will talk to the soup eaters through the prism of our published series of text translations. In parallel, children’s workshops will take place in the garden of the Medical History Museum, thereby highlighting the educational component, which is very important to us.

Then there will be an excursion to the Viktors Timofejevs exhibition at the LNMA, which also marks our collaboration with the museum. And then there’s the Eglītis exhibition in our former exhibition space that is now the Spirits & Wine shop. The grand finale will take place at Bolševička, where we’ve held several of our projects. There will be performances by ‘Nebijušā restaurātori’ [Latvian for ‘restorers of the unprecedented’ – Ed.] and ‘Zvīņas’ [Latvian for ‘fish scales’ – Ed.], who sort of echoed the work of the NSRD [Latvian for ‘restoration workshop for unprecedented feelings – Ed.], as well as a number of DJs with whom we have collaborated over the years. In the morning, Platons Buravickis will give a dawn performance. We also have quite a long history with Platons, as he was the composer who transposed the tape recordings of Hardijs Lediņš’ Kuncendorfs un Osendovskis into a piece for orchestra and voices.

Viktors Timofejevs’ solo exhibition “Other Passengers" at the Latvian National Museum of Art, 2025. Photo: Ansis Starks

If you were to compare young artists – say, those around 25 years old – to those who were 25 years old 25 years ago, would you say that are any noticable generational differences?

You know, ‘the grass was always greener before’ and so on, but I think that back then we had a kind of insane drive – at least the people I was around did. There was this massive boldness and bravery, together with some kind of madness. And survival skills that had been developed in the 1980s–90s. Today’s young people have grown up in a completely different environment. They are definitely more pragmatic; they are not going to rush out to do things, and I think they look at the situation with a cool head – is it worth the effort? 25 years ago, maybe there wasn’t that context, there wasn’t that knowledge...there was more recklessness, more boldness. Nowadays young people are much more concerned about well-being and personal development. I think we didn’t spare ourselves at all – we went all out and gave it 120%.

Maybe today’s younger generation has a better sense of this as a system in which you have to develop gradually, invest in something, and move forward step by step.

Perhaps they just have more knowledge than we had. But there are many young people with whom we work and they have such a bright energy.

Looking at the young artists that you know, what do you think the future of Latvian contemporary art could be?

I think a lot of people are more interested in the commercial aspect of art. I assume that the art market will eventually develop here. Young artists are now working very internationally. Most of them are studying abroad, many of them have gallery experience abroad, and many of them live in several countries at once.

I assume that the presence of the art market will increase, as we have seen in the last decade with contemporary art becoming ‘cool’ and now perceived as a lifestyle element.

Given the current tendencies, i.e. the trend towards conservatism, the socio-political role of art will probably be more difficult to realise...perhaps it will be more subject to an ideological format. In general, it is difficult to predict what will happen and where we will end up. But I would like to hope that one day there will be strong institutions like a Museum of Contemporary Art in Latvia. Well, it has to happen someday, even if the situation is not very hopeful at the moment. I’ve been in at least four working groups that were formed to create this museum, and now it’s in limbo again.

Looking at the non-governmental sector, there are many strong and interesting initiatives, but often these people just burn out. How long can you live in such uncertainty? Of course, the future of contemporary art in Latvia is also quite dependent on the general geopolitical situation – which way is it going? Development of the commercial segment can be spoken about with some certainty. The rest will depend very much on what happens in Europe and the world as a whole.

Another thing that the LCCA does is promote Latvian artists abroad. What do you think – do international curators have a perception of what can be expected from us? Are there any stereotypes?

A number of international curators are still interested in artists who work on re-evaluating their own history, and for them the Soviet period still seems exotic in some way. The Lithuanians are much more active in this sense. There’s also a segment of curators who are looking for ‘post-Soviet echoes’, which can become quite stereotypical. Some expect our artists to be ‘children of nature who know all the herbs’, often putting them in an almost shamanic category and looking for pagan imprints. But many young Latvian artists live and work abroad, and their work is very international and based on international references; often you can’t even tell if you’re looking at the work of ‘a Latvian artist’ or a ‘non-Latvian artist’.

But it is clear that what does draw international interest is when a local story can be told in a global context – your uniqueness is still rooted in some sense of ‘the local’. If you have a personal story, historical references, or knowledge and skills that you can successfully transfer into the context of the language of contemporary art – then that usually attracts people.

For example, the artist duo Skuja Braden. I remember that when we brought Skuja Braden to Venice, our own Latvian art scene was saying things like, ‘What? Are you crazy? What even is this? It’s just crockery and kitsch!’ Yet their work combined extreme technical skill with an extraordinary way of working with this material that went far beyond the traditional use of ceramics, exposing contemporary narratives that are relevant today. It balances on the edge of irony, and the presence of feminist ideas and LGBT connotations make these works unique as well as readable from many levels. Therein lies the key to the success of their work, and it’s hitting right at the topicality of the moment, when feminist aspects are gaining popularity precisely through this artisanal ‘crafts’ approach. Ceramics, textiles, and glass art – historically having been seen as second-class art phenomena – are suddenly coming to the fore and are now highly respected. It’s that moment when you notice something that is working brilliantly here, locally, and you put it into an international context at exactly the right time. Skuja Braden are doing really well in the international art field right now.

Press conference of the Latvian Pavilion "Selling Water by the River" at the 59th Venice Biennale, 2022. Photo: Kristīne Madjare

You went on a big trip before the anniversary of the centre, which probably helped you gather strength and new outlooks...

It was really a once-in-a-lifetime trip. I did it together with Gundega Laiviņa, the former director of the New Theatre Institute, with whom I have a very similar way of looking at things – especially in an artistic and cultural context. She now lives in New York with her partner.

We talked about going on this trip a long time ago, and I had bought my flight ticket before Trump had been elected. It was just a good opportunity at the time, with low fares. When Trump came into power and started creating chaos and deconstructing everything, for a while I thought that maybe we shouldn’t go. Many people said to me, ‘Are you really going now? They’re not letting some people in at the border, they’ll ask you stupid questions...’ But we decided to go anyway – let’s go to nature. And so we did. I did some work in New York – met with some people about a project – and then we went on to California. We actually drove around four states: Arizona, Utah, California and Nevada.

And it was incredible – we travelled more than 1000 kilometres and also walked a lot of kilometres. It was a period of ‘shaking things off’ – both physically and emotionally. The most amazing thing was how much the landscape changed. Within a few hours, you can move from one time zone to another, from desert to mountains, from mountains to forests, and from forests to rivers with rocky banks. There is a power, scale and vastness to nature there that I had never experienced before, even though I have travelled a lot. The twelve days we spent just moving through the landscape were very healing. It helped me clear my mind. Now I feel that I have much more strength as well as more head space to understand many things.

Space for understanding and thinking is so necessary in a world full of messages, signals and impulses.

To be able to think critically – yes, I think that’s the main thing. One of the most frequently asked questions is: What exactly is contemporary art? I often answer that it’s a form of thinking. It’s about thinking; it’s about reflection. It’s not about art as an object, or as an investment, or as a design element in an interior. As purely an object, we’ve probably never been very interested in contemporary art. We are interested in art that has a narrative, a message, an idea.

Art that asks questions. It rarely gives answers – rather, it pokes, provokes, and makes you think. And sometimes it can even be annoying or uncomfortable. But that, I think, is what is important.

Title image: The art park “Mobile Museum. The Next Season”, 2021. Photo: Monta Kaiva Konovalova