Once It Was a Landscape

“It doesn’t have to be your story, or my story – it’s more like a shared, collective weirdness”. An interview with Irish artist Ailbhe Ní Bhriain

The Hugh Lane Gallery is located in the center of Dublin, in a classical townhouse built in 1763, and was originally called the Municipal Gallery of Modern Art. It was founded in 1908 by the art dealer and collector Hugh Lane and was one of the dynamic, pioneering institutions of the Celtic Revival movement in Ireland at the turn of the 20th century. Within its walls you can see Impressionist paintings by Manet, Monet, Degas, Pissarro, and Morisot.

Exterior view of Hugh Lane Gallery in Dublin, Ireland

But this art institution is best known for housing the meticulously dismantled in London and no less meticulously reconstructed here studio of Francis Bacon, the Irish-born painter who fled Ireland as a youth to escape his father’s authority, only to return in the form of the magnificent chaos of his studio after his death. Bacon loved working in complete disorder. He believed that it was precisely in chaos, and in its energy, that the subjects he needed were born. And you can now witness this on one of the floors of the Hugh Lane Gallery.

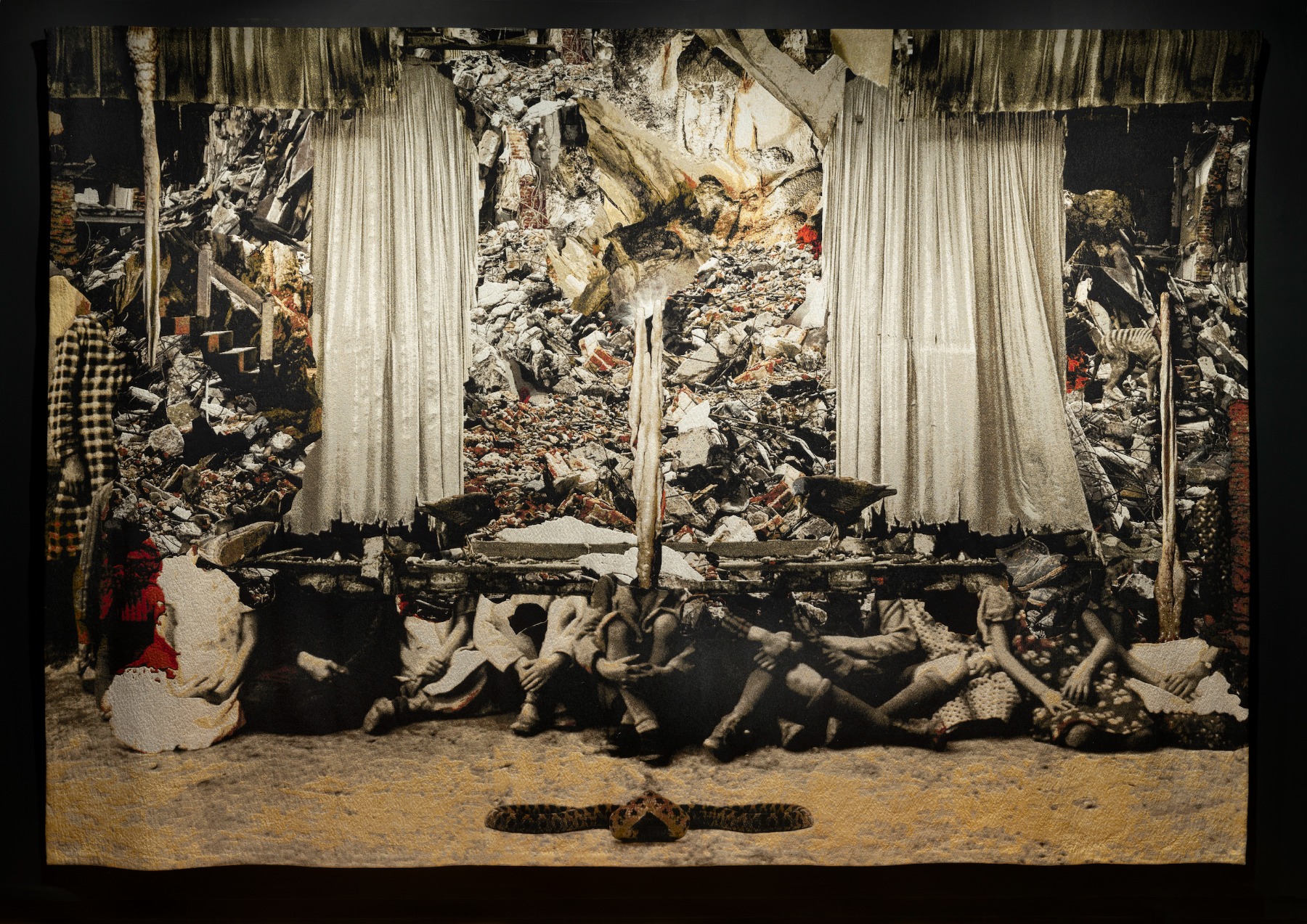

But that was not the reason I came here. What intrigued me was the exhibition The Dream Pool Intervals by Irish artist Ailbhe Ní Bhriain, which is open until September 28th. Ailbhe works with film, computer-generated imagery, collage, tapestry, print, and installation. Her art is deeply rooted in an exploration of imperial legacy, human displacement, and the Anthropocene. I was struck by her monumental tapestries, dense with faceless figures transplanted from old photographs, with ruins that serve as the constant backdrop in this series, with enigmatic animals – the only truly individualized beings – and with stalactites rising upwards. What we see is a kind of space of the post-everything: a world oversaturated with ruins and with the unresolved injustices of the past.

Installation view Hugh Lane Gallery, Ailbhe Ní Bhriain: The Dream Pool Intervals. Image © Hugh Lane Gallery, 2025.

“You were surrounded by the evidence of lots of collapsed pasts,” Ailbhe tells me about her childhood. “It’s this idea of the past suddenly rushing up around us, in a new form, in a new way of seeing us,” she says later. We no longer see any clear picture of the future, but the past – and its unpaid debts – presses in on us from every side.

But there is another crucial theme running through the exhibition – the cave, the underworld, or the “other side,” signaled in the tapestries by the guiding animals and the rising stalactites. And this theme is tied also to the medium of photography itself.

“Camera is the Latin word for ‘a vault, or vaulted room.’ It was combined with the word obscura to describe a ‘dark chamber’ when modern photography began around 1840 – like the Etruscan tombs, it is a dark chamber, with a lens that projects images of external objects and captures time. When photography was introduced in nineteenth-century colonies, indigenous peoples believed it stole their souls, and I feel they may have been right in foreseeing today’s digital colonisation of our behavioural data, invading new territories of the mind,” writes the exhibition’s curator, Michael Dempsey, in his essay.

The ruins of the past, the gaps in the fabric of the present, the ghostliness of what we take for reality – all of this, it seemed to me, deserved a separate conversation. And so, after returning from Dublin, I reached out to Ailbhe, who lives in Cork, over Zoom. The conversation took place in the morning, and while the sun was shining both in Ireland and in Latvia, we were drawn instead to speak about shadows, layers of time, and ghostly landscapes.

Ailbhe Ní Bhriain, Interval III, 2024. Installation view Hugh Lane Gallery, Ailbhe Ní Bhriain: The Dream Pool Intervals. Image © Hugh Lane Gallery, 2025.

When I was walking through the exhibition, for some reason I started wondering what kind of house you grew up in.

Oh, that’s an interesting question. The house I grew up in was almost like a postcard from old Ireland. I lived in a thatched cottage in the west of Ireland, along a small lane that was at one time a kind of a famine village. (In Ireland, "famine" refers to the devastating period of mass starvation and disease between 1845 and 1852, commonly known as the Great Famine or Great Hunger. This crisis was primarily caused by the failure of the potato crop, which was the staple food for a large portion of the Irish population. The famine resulted in the deaths of an estimated one million people and forced another million to emigrate – author’s note). It was an area of commonage – so when people had lost everything during the famine they were allowed to resettle there. At one point I think around a hundred families lived on this tiny stretch. Even now, it’s still peppered with the ruins of old houses.

So, it was an old house?

Yes, I’m guessing about 170 years old. The original cottage is a very basic structure but was tucked into the landscape in a very perfect way. It’s small with thick stone walls and low windows. The area was a quiet farming community, though my parents weren’t farmers – they just arrived there in the ’70s, loved the place and never left.

When I was looking at your works, I started thinking about my own childhood. My grandfather had this old wooden house, and there were lots of old magazines and photos in the attic. I would go through them, and somehow it really inspired me. I wondered if you might have had a similar experience.

My parents weren’t collectors like this at all. What I remember more is playing in the ruins on the lane we lived on – there was a sense of a deeply layered place, which made for an amazing playground. Everywhere the evidence of collapsed pasts. I do remember a trip we took to a recently abandoned island in Galway. My father built a boat when we were kids and we took these great day trips exploring Galway Bay. On island Eddy the houses were just starting to cave in, but they were still full of old LPs and photographs and magazines. It was hard to believe that the records could still be played and the magazines could still be read. Because they no longer seemed like ordinary things. They had this otherworldly quality.

Ailbhe Ní Bhriain, Interval VIII (detail), 2024. Image © Hugh Lane Gallery, 2025

But when did you start getting really interested in photography as a medium? It wasn’t directly from your childhood, was it?

No, my interest in photography came from my connection to the Burren, which is the area where I grew up in Ireland. It’s this very stark limestone landscape – it feels like you’re walking on the surface of the moon. It’s really very beautiful. When I was in art college, I tried to photograph the landscape and I was really struck by how every time you pointed the camera at it, you ended up with a cliché, an image that felt like it came straight from a calendar or a tourist campaign. The landscape has been represented so much and functions as a kind of emblem for an idea of authentic Irishness. This dates back to the Irish cultural revival in the late 19th and early 20th century – an anti-imperialist movement that was attempting to reclaim Irish culture but which was also – inevitably – reinventing it.

So this was a bit of an epiphany for me, properly understanding the photograph as a construct for the first time. And for the first time considering the cultural and political baggage that these constructs carry. There was no way to photograph this place without connecting to all these layers of performed identity. That’s what drew me in.

I guess that’s the thread linking to Victorian photography for me. I’m interested in the performance involved in those Victorian photographs, and their connection to an imperial past. The more you look at the portraits from that era, the more you see that they are encoded with the ideologies of the time – the way people are positioned like assertions of superiority, and the way the props and backdrops used often reference empire. There is a whole story being told that is much bigger than the individuals represented.

Ailbhe Ní Bhriain, Interval II, 2024. Installation view Hugh Lane Gallery, Ailbhe Ní Bhriain: The Dream Pool Intervals. Image © Hugh Lane Gallery, 2025.

The figures in your works, taken from these old photographs, aren’t really individuals, because they don’t even have faces. Instead of faces, they have small areas of darkness, I would say… What kind of darkness is it?

Yes, sometimes the faces give way to glimpses of rock formations, other times to destroyed cityscapes, and other times… it’s just the void. When we look at photographs, we are immediately drawn to the face – we automatically make the individual the centre of every narrative. By removing the faces, I’m trying to draw attention not to the individual, but to people as players within a wider project.

So when you look through the face in these tapestries to see contemporary destroyed buildings and scenes of ruination, you are seeing the present-day aftermath of those Victorian forces of imperialism and industrialization. And when you look through to see subterranean spaces – these underworlds of caves and tunnels and stalagmites and stalactites – you are seeing this very different, ancient register of time. It’s not human time anymore; it’s the deep time of geology – another way of understanding the world.

I think there’s something so poignant about the way we pose for photographs. It’s like we’re looking into the future, trying to preserve ourselves and control time. I’m drawn to the folly in that – the idea that we can ultimately control anything. So in these tapestries we encounter a kind of point of collapse – with the polite portrait being engulfed both by an ancient past and a destructive future.

Ailbhe Ní Bhriain, Interval III (detail), 2024. Image © Hugh Lane Gallery, 2025

It makes me think about ghosts too – how we traditionally see them in our cultures, as figures without faces. And it’s almost like you have some kind of camera obscura for looking at them. It’s a reminder of how much has happened in every house with a hundred or two hundred years of history, or in every place.

I’ve never thought about that explicitly, but I’m absolutely trying to make the imagery permeable to many possible meanings – so yes, maybe I am inviting ghosts in!

Our interest in the past, in terms of collecting, documenting, archiving, is always about the future – a world preserved and narrated for a future audience. And now we’re in this very strange collective moment, where we’re suddenly confronting a deeply uncertain future. I think the weirdness of this realization sends a serious tremor through our understanding of the past – and yes, probably lets loose a few ghosts in the process.

Ailbhe Ní Bhriain, We have reached a certain depth (I), 2023. Image © Hugh Lane Gallery, 2025

And we do see these ghosts all around us – all these unrealized projects, unfinished histories, untold stories. And of course, the postcolonial subject is also present.

I’ve always been interested in the Irish position in this postcolonial sense, because it’s quite layered. In a very real sense, we were the colonized and the oppressed. But then there is also the parallel, less retrospectively comfortable reality that we operated as the oppressors too. We became part of those colonising systems – serving the British civil service, the British army and the Catholic church in their various missions. These were all ways to ‘get ahead’ in Irish society. So choosing only to shape our memory around our role as victims denies a more complex legacy.

The artist Maud Cotter, when she talked to me about her encounter with the Interval tapestries, said that for her they ask the question “who is the accuser and who is the accused?” I like this ambiguity. I’m not trying to take a position of finger wagging or doom-mongering in these works. It’s more like, look at where we are collectively: we are in this very existentially weird space, with all our familiar systems, even something as huge and ancient as our weather system, suddenly tilting towards calamity. And maybe, before we distract ourselves away from the discomfort of it, or sink into guilt-induced self-loathing, maybe we should just reside in the weirdness for a while. To kind of open ourselves up to the strangeness of it all. I do think that’s worth doing.

It lets you see outside of the false binaries that are crowding around us, the false arguments and overly certain positions that become the greatest distraction. That’s probably what I’m trying to reach in these images: the space for ambiguity. Where it doesn’t have to be your story, or my story – it’s more like a shared, collective weirdness.

Ailbhe Ní Bhriain, Interval VII, 2025, Jacquard tapestry. Installation view Hugh Lane Gallery, Ailbhe Ní Bhriain: The Dream Pool Intervals. Image © Hugh Lane Gallery, 2025.

But what really concentrates the strangeness is the material form itself – the fact that it’s tapestry. These are ghostly images, but at the same time so present and material. The tapestries are huge in scale; they’re not just flat surfaces. Because of their weight, they take on a shape of their own, and with the use of different threads and materials, the surfaces vary. So the strangeness is also very material, embedded in their physical presence.

I’m totally besotted with the exact qualities you’re describing – that deep materiality of the tapestry and how dynamic it becomes. Like you say, there’s a lot of variety in the yarn – most of the tapestries are shot through with Lurex, sometimes several Lurex threads, so there is this kind of metallic, glittering current running through the image. Getting the right balance in each piece between Lurex, silk and wool takes a lot of testing, but it turns the image into something very alive and dynamic.

I think I’ve always been restless when it comes to the surface of an image: it goes back to this discomfort with photography and the idea of the fixed narrative it carries. Weaving physically disrupts that fixity and continually transforms how you see the image… the tapestries respond dramatically to changing light, they fold and distort under their own weight, they allow for so much surface-play through the use of relief and different bindings. I studied printmaking, which tends to involve a long multi-stage process to coax out an image. I think I became attached to the emergent image in these processes – something that seems caught between a state of becoming and a state of dissolving.

Ailbhe Ní Bhriain, Interval VII, 2024. Installation view Hugh Lane Gallery, Ailbhe Ní Bhriain: The Dream Pool Intervals. Image © Hugh Lane Gallery, 2025.

Ailbhe Ní Bhriain, Interval VIII (detail), 2024. Image © Hugh Lane Gallery, 2025

The tapestry’s material evokes the Victorian and imperial context – rich houses, grand carpets. But the mission of your tapestry is completely different, of course.

Yes, tapestries were historically such symbols of wealth, objects that signified status. So I do enjoy working with the medium to depict these shards of imperial aftermath. But I’m specifically working with Jacquard tapestry, which as a process also connects directly to industrialisation and social upheaval. When the Jacquard loom was invented in the early 19th century, its promise of automated production posed a huge threat to existing textile jobs and led to historic workers’ riots. The loom itself represents the first practical application of binary code – in a way, it functioned like the earliest computer. I was drawn by these links, both to the histories of imperialism and industrialisation. And right now, when we are all obsessed and confused by AI and emerging technologies, it resonates even more: thinking about how these technological shifts can transform or enforce existing power systems.

Installation view Hugh Lane Gallery, Ailbhe Ní Bhriain: The Dream Pool Intervals. Image © Hugh Lane Gallery, 2025.

But in the other space of your exhibition we see a line of vases that look almost antique, but as I understand it, they have no real museum value – they’re just pretending. What are they, and why are they there?

Within this exhibition there are a lot of references to the underworld – this mythological, subterannean zone that was used across so many cultures to frame our understanding of death and fear of the unknown. The recurring imagery of caves relates to this, as do the animals that keep appearing – animals, now endangered, that were once believed to act as messengers from the underworld or companions for our journey to the afterlife.

The clay vessels also link to this idea of the underworld. There’s a whole history of these kind of vessels being found in tombs and burial sites, and the role they played in death rituals. It’s mostly speculation of course but it’s believed that they were used both to prepare the body for the afterlife, as well as holding offerings to accompany the dead on their passage. A lot of the vessels that we now encounter in museum vitrines once belonged to burial sites.

In this exhibition I wanted the presentation of these objects to reference aspects of museum display but also to take on an odder, more ritualistic presence. Each vessel sits on top of the Perspex container that would normally enclose it, and is partially filled with carbon. I was looking for a kind of fusion between the language of museology and the language of the underworld!

I actually started collecting those vessels around the same time I began working on my first tapestry, from a series called The Muses. The series draws on western portraits of colonial subjects – often boudoir-style postcards, basically western fantasies of the exotic and the erotic. In the original photographs many of the women are holding these large clay vases and vessels. The repetition of this motif really alerts you to the staging of it all, and the fact that both women and objects are being reduced to props.

Over a period of years, I began collecting vases that reminded me of these images. They’ve been gathering in the studio for a long time, with no set plan for use. But as they’ve accumulated they kind of developed their own authority and attached to my thinking around underworld lore. I like how this happens in the studio, the way objects or images, by sheer proximity, start to influence each other and shift meaning. Really we’re all collaging all of the time, telling ourselves a coherent story by connecting disparate fragments. We just do it instinctively, then believe in it fully. A collection of any kind is also a form of storytelling, a little fiction.

Ailbhe Ní Bhriain, Picture V, 2025. Image © Hugh Lane Gallery, 2025

But they’re also surrounded by these large prints of your works, which, as I understand, are almost like the backsides of old photographs – extremely zoomed in, abstracted, or transformed in a way that emphasizes texture and detail rather than the original subject.

These images show the reverse side of a series of found photographs. I scan the ‘blank’ sides of these images at very high resolution, after sometimes working into them by hand. Often, the original photos are very small – tiny snapshots from the early 1900s, so this process transforms them into something entirely new – both abstract and highly detailed.

There’s a sense for me of always trying to get behind an image – almost a childlike hope that I might reveal something or access the thing that lurks beneath. It’s the same impulse of collage: cutting through, opening up, trying to get beyond the surface and into that imaginary depth.

I also have this notion of a fictional future in which all these old archives of photographs are found, but with the ink faded – the events, the faces, the facts all vanished from the record. All that remains are the objects themselves and the fact of their collection. I imagine something strangely elevated attaching to these objects in this context, a new unknowability that grants them an almost spiritual status. They become a new kind of story, one of purely projected meaning.

In another space of your exhibition, there is a very small photograph, more than half of which is covered with black paint. For me, it feels like it’s about the impossibility of fully reaching the image or its meaning. What was your idea behind covering it with this black surface?

The black material is bitumen. It’s a byproduct of crude oil – and a material that’s also connected to printmaking, used to coat the back of metal plates. Bitumen has this strange quality that feels both elemental and highly synthetic. Covering the photograph with it transforms the photograph from image to object. The story it thought it was telling gets swallowed up.

I like introducing these materials that link to the industrial and subterranean. The photograph is obliterated by crude oil. The clay vessels are filled with carbon. And the tapestries all carry this sense of something buried, threatening the image from beneath.

Ailbhe Ní Bhriain, Untitled (surface #6), 2025, found photograph, bitumen paint, Image courtesy the artist, domobaal & Kerlin Gallery, Dublin. Photo credit: Roland Paschhoff

But what was originally in this small picture?

It was a landscape. Once it was a landscape.

Title image: Ailbhe Ní Bhriain at the exhibition opening of The Dream Pool Intervals at Hugh Lane Gallery © Naoise Culhane Photography 2025