Close-close cosmos

Estonian artist Tanja Muravskaja talks about her exhibition Gardens: Tanja Muravskaja and Light, one of the highlights of Tallinn Photomonth 2025.

After many years of working with themes of identity, politics, and social critique, Estonian artist Tanja Muravskaja experienced a kind of “intoxication” and “oversaturation.” She began to search for a form of refuge – a new kind of internal space for expression.

The first step in this direction was her project The Garden of Exile: The Garden of the Tuglas Couple (2019), presented at the Kumu Art Museum. It was inspired by the Estonian writer Friedebert Tuglas, who, after being expelled from the Writers’ Union in 1950, found both solace and a creative anchor in his garden. Since then, for Muravskaja, the garden has become a symbol of an inner refuge during turbulent times.

Exhibition view: Joosep Kivimäe/ Tallinn Photomonth

In her new exhibition, open in Tallinn until the end of October, the garden is present in a metaphorical form. The exhibition takes place in the Saarinen House, one of Tallinn’s iconic Art Nouveau buildings. The space used is “raw,” bare, and unfinished – the top floor with its windows deliberately dimmed, isolating the visitor from the city’s visual and sonic noise. The acclaimed artist and sculptor Evgeny Zolotko, acting as scenographer, constructed white columns specifically for the show – extensions of the building’s internal architecture. Their placement prevents the viewer from taking in the entire space at once; one must walk around, viewing from multiple angles. This already evokes the experience of a stroll and contemplation – a walk through a garden.

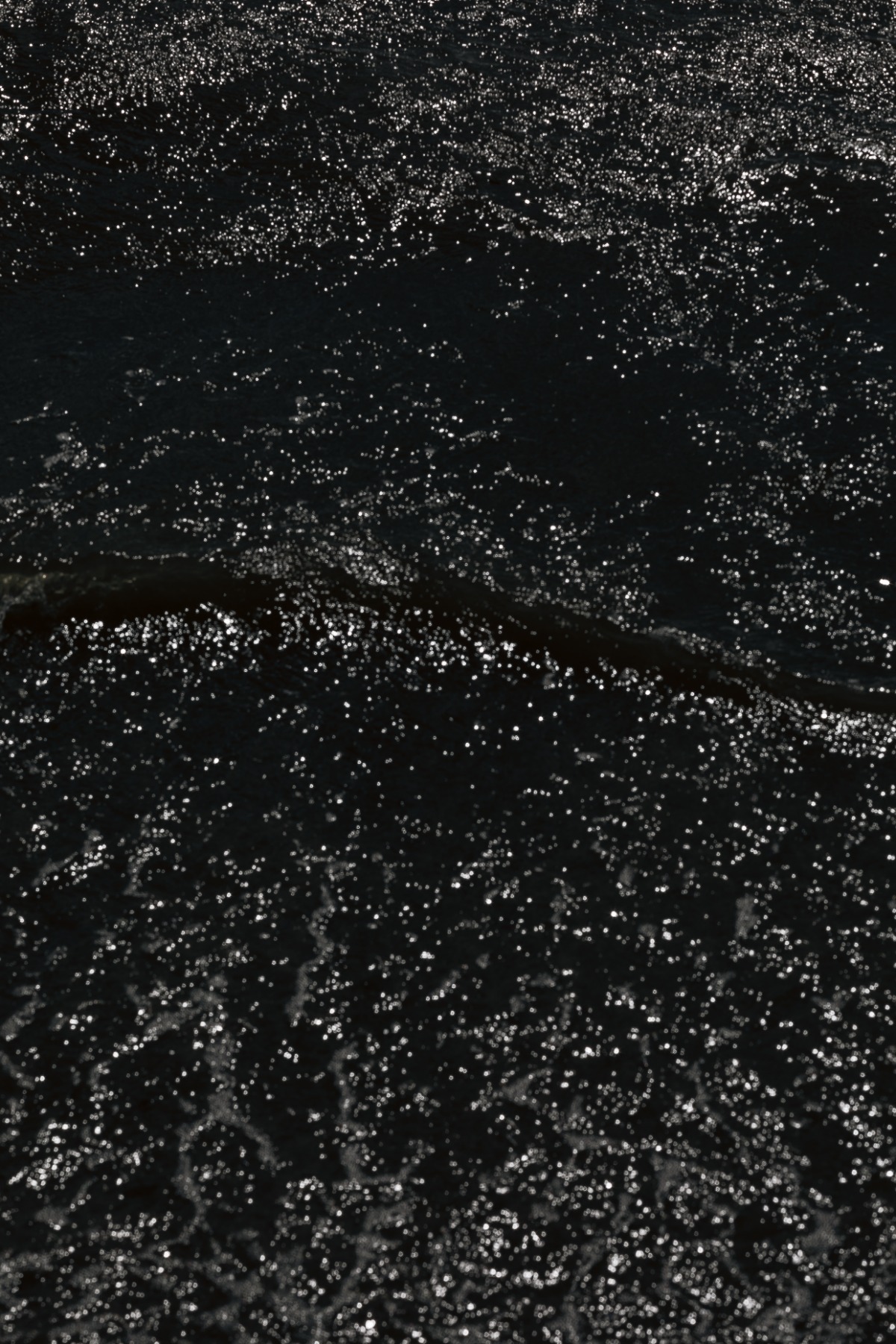

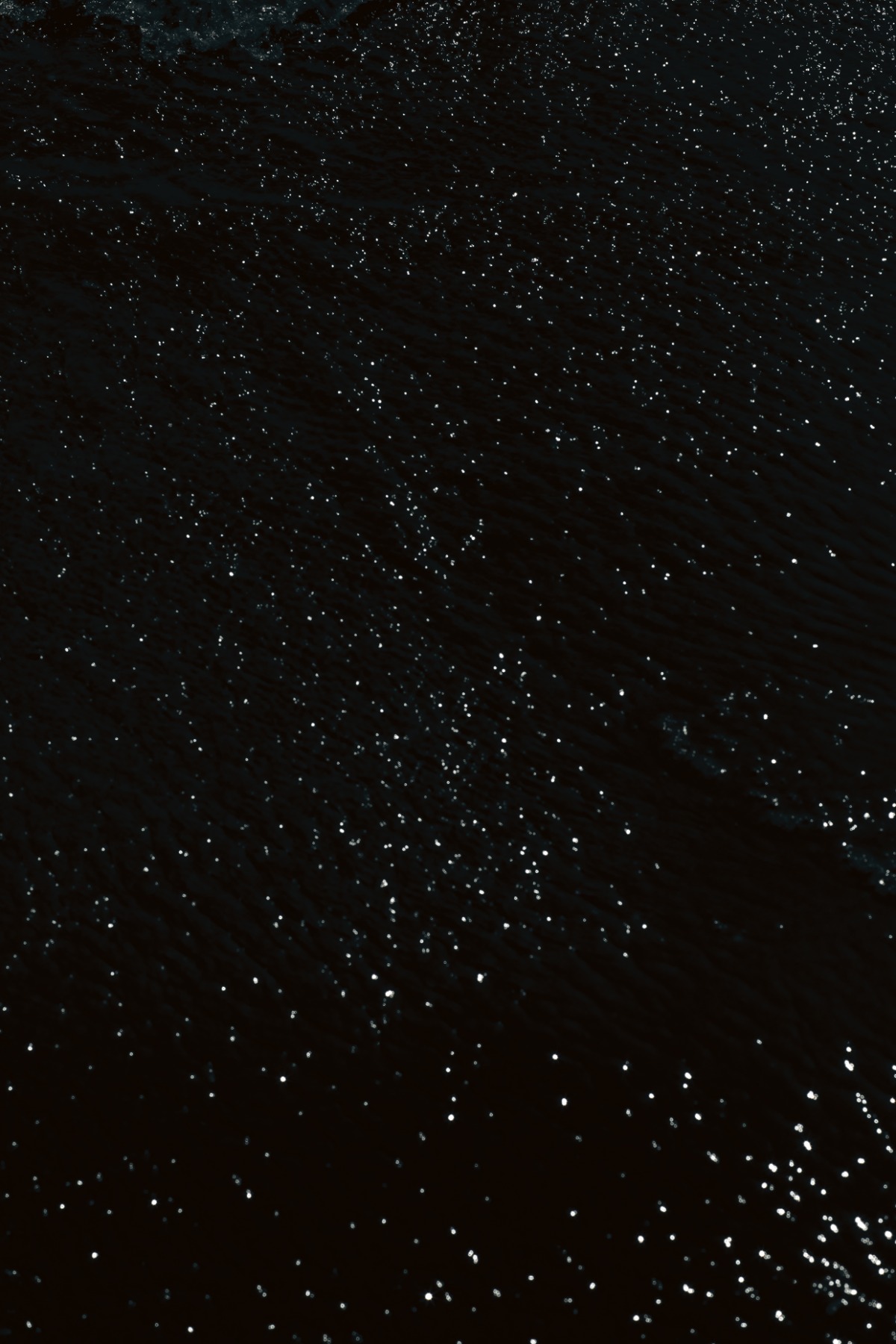

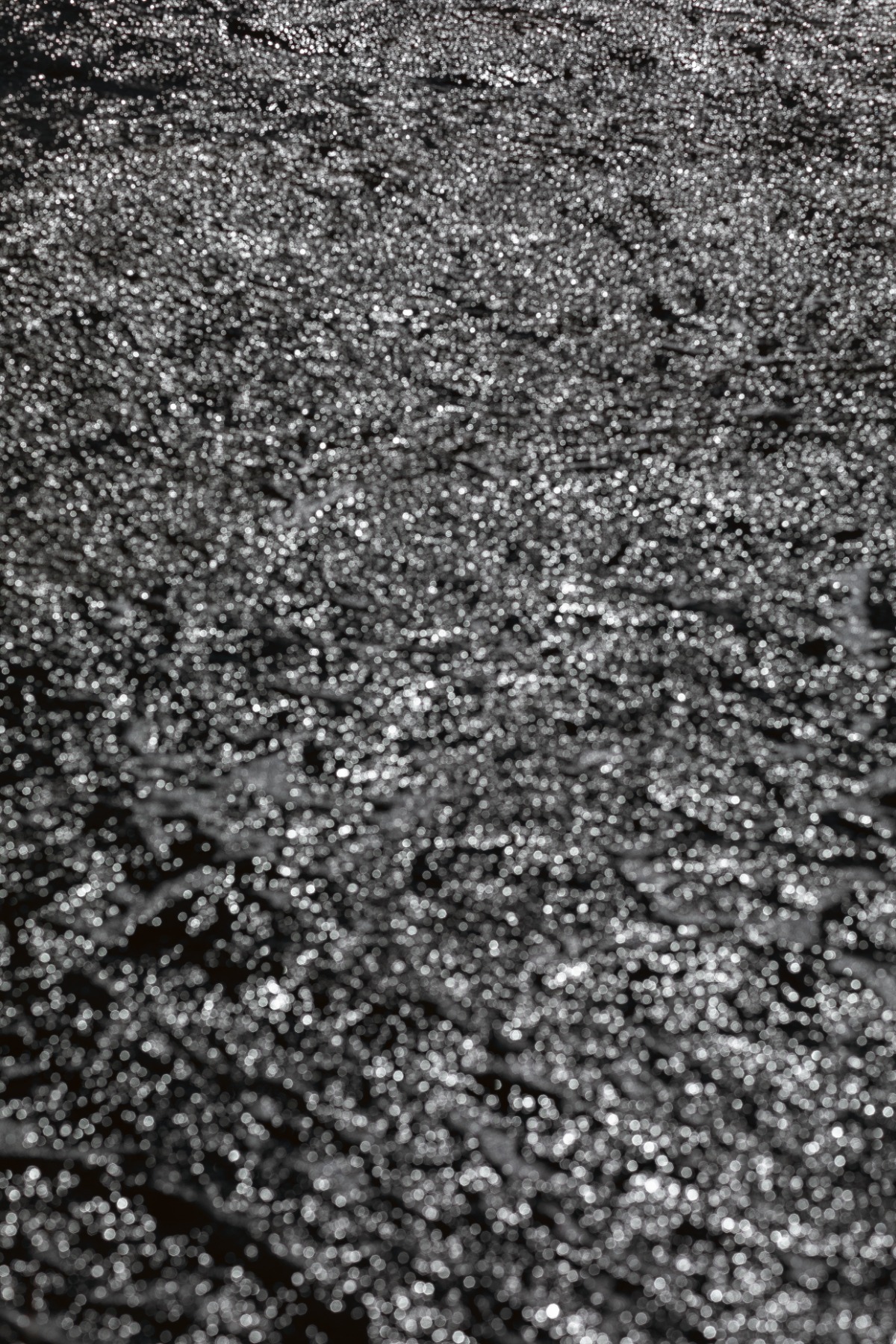

In this new body of work, Muravskaja consciously moves away from overtly political or socially critical statements. Instead, she offers what she calls a “silent, empty utterance” – a gesture that refuses to engage with any known ideological frameworks. Her works are photographs of the sea, taken in her hometown Pärnu. It might sound simple, but the dark, almost oil-slick-like expanses of water in these large, meticulously framed prints – shimmering with reflections that fracture the world (or our view of it) into black-and-white atoms – resist immediate reading. To understand how the artist herself sees them, we met her on the top floor of the Saarinen House, in the quiet of the exhibition space.

Tanja Muravskaja. Gardens. 2025. Digital chromogenic print, mounted on aluminium, framed in Showcase frame with museum glass, photo size 165x110.0 cm, frame outer size 168x113 cm. Series of 14 photographs

Tanja Muravskaja: This is my first time exhibiting as part of Tallinn Photomonth, although I’ve collaborated with the festival before – I curated a show of the Ukrainian photographer Boris Mikhailov, who lived in Berlin, and a Baltic photography exhibition exploring the 1980s.

My name has long been associated with figurative photography, with an interest in the new Estonian identity that emerged after the 1990s. I’ve done portraits of politicians, artists with flags, scouts, soldiers… those were my central themes. But over the last four or five years, I’ve felt an increasing need to step away from the saturation of political and socially critical discourse. I began searching for a kind of refuge – a garden as refuge – not an escape, but a new form of of inner recalibration. A space for restoring perception and language.

The first project in this direction was created for Kumu, together with curator Elnara Taidre, and was titled The Gardens of the Tuglas Couple. I was fascinated by how, for the modernist writer Friedebert Tuglas, the garden became such a refuge after he was expelled from the Writers’ Union. He became a persona non grata, withdrew into his house and garden in Nõmme, a district of private houses within Tallinn. Hardly anyone visited him; he lived there in seclusion and wrote. He and his wife also began photographing their garden – perhaps as a therapeutic act.

Since then, the theme of the garden, the search for some inner foundation, a shift of perspective – all this has increasingly occupied me. I used to work intensively with the theme of identity, of finding one’s place, of memory. My parents are Ukrainians who moved from Ukraine to Estonia, where I was born. All our relatives live in Ukraine – some are fighting, others live in towns and villages.

And I thought: this is a time when those who are truly in pain can and must speak. My role, perhaps, is to make more space. This is a silent statement – an empty one – which the viewer can fill themselves. These works are simply an entrance to somewhere, or something like windows.

Tanja Muravskaja. Gardens. 2025. Digital chromogenic print, mounted on aluminium, framed in Showcase frame with museum glass, photo size 165x110.0 cm, frame outer size 168x113 cm. Series of 14 photographs

Windows onto the sea?

Yes, the sea, photographed in Pärnu, where I was born. At first, I shot on film, but of course, you can’t control the element – you can’t repeat a frame. I’ve always followed the principle of leaving the shot unchanged; I control it only at the moment of taking it. So I had to switch to a digital camera, and I photographed the sea for an entire year.

Gaston Bachelard, in his book Water and Dreams, wrote beautifully about water. "The image of the mirror of water is an image of double nature: it gives us both presence and absence, appearance and disappearance". He saw in it an ideal symbol of the time “between beginning and end” – constantly in motion, transforming, yet never fully existing in any one state. The ripple, the reflection – it begins, and a moment later it’s gone. I tried to capture precisely that event “between beginning and end.”

These colour photographs are printed on a soft, almost velvet-like paper – thin, tactile, like skin. I printed them myself. The process of printing is, for me, an essential part of authorship.

Exhibition view: Joosep Kivimäe/ Tallinn Photomonth

But you say they’re colour photographs? They look rather monochrome.

Yes, they are colour. I love setting myself strict boundaries I must then overcome. I had only exposure and aperture – and focal distance. Within that, I tried to find this way of seeing, this gaze. That is, the exposure is very short – for example, 1/5000 of a second. And that’s how you get this dark background, this dark space. For a long time, I searched for what could be “nothing” for photography – something completely abstract. You can experiment in the darkroom, of course, but that felt artificial, a constructed world. I wanted to find something that already exists around me – to make it a gateway to another dimension.

And in Pärnu, where I spent my childhood and lived until I was eighteen, I was able to rediscover that childlike joy of encountering the elements – to feel again the emotions of a child. In the Estonian art scene, we tend to stay within strict conceptual frameworks. It’s usually modernist artists who speak of such things – the sea, the elements, and so on. But here, the sea simply became a ready-made surface, a living extension of the work itself.

The sun’s reflections – usually in the middle of the day, when the light is strongest – remain white in the frame, no matter the exposure or aperture. They become points of entry.

Tanja Muravskaja. Gardens. 2025. Digital chromogenic print, mounted on aluminium, framed in Showcase frame with museum glass, photo size 165x110.0 cm, frame outer size 168x113 cm. Series of 14 photographs

Were you concerned about how people would react to such a sharp turn in your work?

You know, I recently went to Basel specifically to see Vija Celmins’ exhibition. In her works, I recognised the direction I had already been intuitively moving towards. That coincidence of vision gave me a sense of inner confidence.

Seeing her works in Basel, I realised that I had to move further – that there’s still so much to be done photographically.

Tanja Muravskaja. Gardens. 2025. Digital chromogenic print, mounted on aluminium, framed in Showcase frame with museum glass, photo size 165x110.0 cm, frame outer size 168x113 cm. Series of 14 photographs

But Celmins paints her works, doesn’t she?

She does. But she also wasn’t afraid to appear naïve or even absurd. Why paint what you could photograph? Or create what is already visible? Immersing yourself in the process, you constantly have to answer such questions. In her canvases – some large, some very small – you can sense that quiet courage and precision of thought.

How did you decide on the scale of your works – the way we see them in the exhibition?

I thought a lot about that. The chosen size allows for performative interaction with the image – you can step closer, study it, step back again.

An exhibition of photography should always have a kind of cinematic rhythm. Within a series, you create dynamics, tension – an internal scenography.

For me, this show is also a radical gesture: a step towards freedom from stricts expectations. But for me, this exhibition is also a radical gesture in the sense that this project became a step toward freedom from previous expectations. Everyone expects me to create portraits of Ukrainian refugees, certain politicians, or installations on pressing topics… But when your visual language has been honed for quite some time for sharp statements and serious dialogue, I think the truly radical thing is to find another form of expression – non-verbal, bodily, visual. Then the viewer receives air – and can fill it, or not fill it, with meaning. That freedom belongs to them.

Exhibition view: Joosep Kivimäe/ Tallinn Photomonth

Here there’s an optical approach that both brings the sea closer and simultaneously feels like a view from space – a cosmic gaze on how we live here. Because what’s happening to us also has something cosmic about it – the movement of uncontrolled, partly unknowable forces.

Yes, perhaps we really should look at ourselves from a greater distance.

The exhibition will remain open for two more weeks…

And I would really love to show it someday in Latvia. Where people know Vija Celmins’ works, maybe mine would resonate more deeply. You always imagine there’s an audience somewhere who will understand you more completely. I truly want a dialogue with a viewer who knows those cosmic paintings of hers – who might find more associations, more reflections.

When I discovered her works online, I asked Zuzeum to send me some reproductions – they have a few. But that’s nothing compared to seeing them in person. It was extraordinary. I watched a film about her and visited the exhibition three times. In that blackness she creates in her cosmic paintings, there are so many layers – so much space in that darkness. As a viewer, I feel I can breathe there.

And when I saw this, I was no longer so afraid to open my exhibition.

Tanja Muravskaja. Gardens. 2025. Digital chromogenic print, mounted on aluminium, framed in Showcase frame with museum glass, photo size 165x110.0 cm, frame outer size 168x113 cm. Series of 14 photographs

There’s also a fascinating physiology of vision here – the glares, reflections – as if the gaze isn’t in full focus, or as we say, you’re “looking from the corner of your eye”…

When the world is so full of horror, sometimes you just want to close your eyes. My cousin is in Kyiv – I message her on Telegram, waiting in tense moments for a reply, wondering if it will come at all… It’s hard to describe. Something cold settles inside you. There’s a physiological desire to close your eyes – and yet, you have to keep moving through life, keep looking. You can’t walk completely blind; you just half-close them.

And in the place where I was born and spent my childhood, you often look at the sea and the sun with half-closed eyes – through your eyelashes, and you begin to see a kind of blur, forming landscapes out of light. Those glimmers turn into something like…

Pictures?

Yes, pictures. I don’t go out searching for something to photograph – “here’s a beautiful place, let me shoot it.” No. It starts in my mind. I formulate it, build it, test whether it’s worth pursuing, whether I should try another direction, another medium.

When I realised that “through my eyelashes” I was still seeing something – that was the space I wanted to create. This very close space.

And at the same time, very cosmic.

Exactly.