We’ll figure it out

Interview with Edd Schouten, Artistic Director and Curator of the Riga Art Space TUR

If you have ever been to an opening at the art space TUR, located in Riga’s Tallinas kvartāls, you could hardly miss the tall, distinguished man, who warmly and kindly welcomes visitors and tells everyone interested about the exhibited projects and their authors. This is the Dutch curator Edd Schouten, who has been leading the space for several years now and working there in one team with Kristīne Ercika and Ada Ruszkiewicz. The space itself is truly impressive – a huge cube with very high brick walls, concrete ceilings, and a large number of windows. And every exhibition that takes place here rethinks the space and its scenography in some new way.

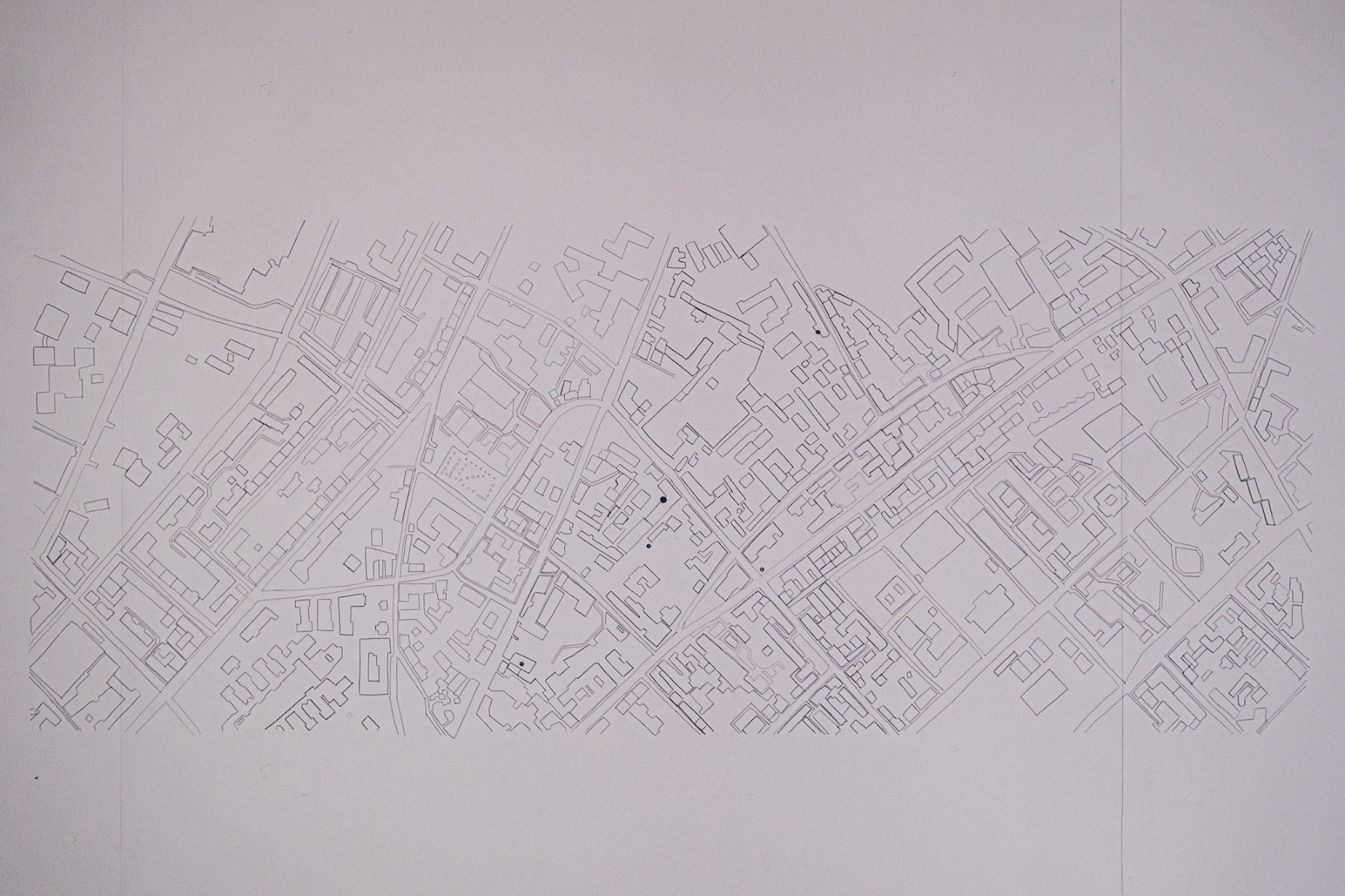

This January, TUR opened an exhibition by the emerging artist Oto Holgers Ozoliņš titled Artifacts of Process (on view until 7 February). And once again, upon entering through the massive doors, an amazed “wow” escapes you. In front of you stands the cabin of an old Soviet ZIL-130 truck, empty and without wheels, and on the truck’s chassis a kind of “house” made of wooden panels has been erected. Inside, there is an entirely white space with a stove in the centre – a clear reference to the traditional definition of gallery space as the “white cube.” On the wall hangs a map of the area surrounding TUR – only the outlines of buildings and streets, without any names or markings.

Oto Holgers Ozoliņš. Artifacts of Process. 2026. Photo: Dāvis Drēziņš

As the curatorial text explains, Ozoliņš’s practice is rooted in process-based sculpture, “where personal growth and the countering of idleness are central. During the lockdown, he carved a wooden spoon each day for 400 consecutive days, a project that led to his first solo exhibition. This disciplined, habit-building approach has since expanded into attempts to build a boat, quit smoking, run a marathon, and complete an Ironman triathlon. Each endeavor transforms his understanding of how form can emerge from repetition and constraint. For this exhibition, he extends this inquiry, turning the act of foraging for wood into a daily ritual and artistic score and exploring how it can be placed into the context of “the exhibition”.

Oto Holgers Ozoliņš. Artifacts of Process. 2026. Photo: Dāvis Drēziņš

But January also brought other news – a couple of weeks ago Edd Schouten was nominated for the Latvian Annual Art Award as Curator of the Year. At the same time, from 13 February onwards, visitors will be able to see the large-scale exhibition Collections at Zuzeum Art Museum, also curated by Edd. About his mission at TUR, the new exhibition in this space, and the upcoming show at Zuzeum, we talked in person – we met at the Orbīta office on Ģertrūdes Street. I mentioned to Edd that Orbīta once had its own big space – the Elektrocehs – at Andrejsala. But gentrification long ago buried the hopes connected with that territory. Edd told me he is afraid that Tallinas kvartāls might face a similar fate – at the end of last year it got a new owner: the territory and buildings were bought by the company Winfinity, which, as Edd says, is planning a major redevelopment of the complex of buildings adjacent to TUR.

For now, it is not very clear what kind of future awaits TUR in a year or two. “And it probably means the end of TUR, because what is the point of this place? It’s very much about the space — and the size of the space, too. I think one of the things we offer the art scene in Riga is precisely that: we have this scale available, and we have a dialogue with the space. This is the unique character of TUR. How I curate exhibitions here is by treating the space as a collaborator, rather than merely as a neutral container”.

It would be incredibly sad to lose a place like this, founded just five years ago, and it would be a real loss for Riga if we were to be deprived of Edd’s experience, ideas, and charisma. Let’s hope, as Edd says in our conversation, that “we’ll figure it out.” But first of all, I would like to find out…

Edd Schouten. Photo: Inga Erdmane

How did you get involved in the “TUR process”?

First, I had an exhibition in TUR in 2022. Rūdolfs Štamers, one of the founders of the place, subsequently asked me for feedback. One thing I said was: you consider yourself a curated space, but you’re basically just choose the artist and give him the key. Sometimes that works, if the artist knows how to make an exhibition, but if they don’t, you’re not really offering anything except the space. After that talk, Rūdolfs suggested I try curating. I thought, why not? It’s an interesting project and a very interesting space. I said I’d do it, but only if we also had a winter programme, because winter stories are just as important as summer ones. My first three shows in winter 2023 were with people I already knew. I wanted relationships I could trust. And immediately you see it’s not only about curating: there’s social media, publicity, identity, etc.

From my background as a choreographer, I work with movement, time, and space. That became the starting point. TUR became something I could observe in motion: how space, time, and people move together. That’s at the core. But there are all these other things moving along with it: how do you get funding; how do you pay the artist? That’s a really important element. It’s surprising how many art spaces still don’t pay their artists, even when they’re making solo shows with them. In the Netherlands you have a guideline that art spaces and museums are obliged to follow, which is based on the minimum wage. So, when you invite an artist for a solo show with new work to be shown for two months you have to pay around 13.000 euros. I’m not sure it’s always good, because it can make it difficult for smaller spaces to invite artists, but it’s certainly important that an artist gets paid.

Here in Latvia the budgets are very different, of course. Anyway, the first thing in our budget is always the artist fee and material costs. We want to support artists so they can stay in Latvia and not feel they have to move to the Netherlands, France, or the UK to make a living. If you’re successful, the opportunities outside are much bigger. So how do we create conditions where artists can stay in Latvia and still grow?

Of course, they should also have shows abroad. We try to bring artists outside Latvia and create new opportunities. It’s very exciting that Liga Spunde will have a solo show at 1646 in May. 1646 is one of the premier contemporary art spaces in the Netherlands, and that came from the show we had here. She was part of that. Last October we presented three Latvian artists at Sofia Art Fair. It is our intention to participate in an international art fair again this year.

I think the quality of art in Latvia is really high. There’s a kind of canon, a tradition where this generation of artists refer to the generations before. Now we have this new show by Oto Holgers Ozoliņš, and you can’t not see Andris Eglītis in that kind of work. There’s always this looking back at what has come before and at previous generations, and I think that’s really valuable. But there are also fundamentally Latvian issues that come through the work.

And Oto going around and finding wood – it’s also very Latvian story. It’s like going to pick mushrooms in the forest – this way of finding how to supplement. Maybe the money isn’t very big in Latvia, but there are ways to supplement your income through nature. You supplement your food through the garden, through picking, through foraging, but also through repurposing. You don’t throw things away so easily. And maybe this is even stronger in the artistic community – how to salvage, how to repurpose, how to find ways to make things work. A lot of people are very handy, in a real “do-it-yourself” manner.

Which I’ve also become. I used to be the type of artist who would say, “Okay, I need a hole here, there, and over there. And in the meantime, I’ll go get a coffee for you.” Now, I’m on the lifter with the perforators, drilling holes in the ceiling – and I love it. “It has to be done, so we do it.” I think it comes, in part, from this Latvian attitude: we’ll figure it out. You can achieve so much without just buying everything. I really appreciate that quality, and you can see it in the work of many Latvian artists.

I’d even call it a bit of “trashiness.” Maybe the artist can’t afford the materials they would use otherwise – but they can still use these and communicate their idea, bring it to life. I say “trashiness,” and I know it sounds almost derogatory – but I don’t mean it that way. I’m just saying it can become its own kind of aesthetic, where you don’t have to worry so much about how clean or polished something is.

Oto Holgers Ozoliņš. Artifacts of Process. 2026. Photo: Dāvis Drēziņš

In that sense, we could mention Oto’s exhibition again. Could we even say that, in a way, it literally comes from trash – from things people throw out?

Well, let’s not call it trash – first of all, because it’s a combination. There are some new materials, too. It’s really about taking things that are no longer needed for their original purpose and reusing them. Otherwise, they’d probably just sit and rot. We even have this at our house: there’s a trash can, and behind it, furniture that’s been there for months. Someone moved out and threw it away, and it just sits there. So yes, it’s trash on the one hand – but I think of it more as “material with potential.”

Oto Holgers Ozoliņš. Artifacts of Process. 2026. Photo: Dāvis Drēziņš

For sure, wood – and things from wood – are always something more than trash.

Yeah, exactly. But it’s also in our tradition – the whole cuboid that we built already a year ago in 2024 – all the materials were already in TUR, all of it. They’d been there for years, I guess, just sitting around, always in the way. There wasn’t anything except some screws and that sort of thing that wasn’t already in the space. And so, it was really, really pleasurable to take all of that material and just make something new out of it. So, yeah, wood definitely – but also other materials, maybe a little less easy to use. I think that in Oto’s case, he also works with aluminium.

I know that for his work in Liminal Limbo, the group show in 2024, he cast these little soldiers, these figurines of soldiers that kids used to play with. Back in the old days, they were made from aluminium. And he made larger figures out of them. I think he also used metal from wheels, melted it down, and turned it into art material. So, he’s been doing that for a while.

Now he’s taking parts of the truck, which he brought into the exhibition – this old ZIL 130. It’s like that truck once drove in here and ended its existence, because it could no longer move – but then, on the same chassis, he builds the house. But it’s also the source of materials – there are these cutouts in the truck that he’s just sawed out, and they’ve been used to make additions for the exhibition. The steel from the truck is being reused, and he’s turning it into artworks.

Oto Holgers Ozoliņš. Artifacts of Process. 2026. Photo: Dāvis Drēziņš

Oto goes around the district near TUR, gathering wood and other materials. Some of that wood he uses in his works, and what’s left he burns for heating in the self-made house – built from wood pieces and constructed on the chassis of the ZIL-130. And that’s how the small onion on the windowsill of the house can grow.

One of the other things he does – he draws this map, basically, that marks and commemorates where he found the wood. He also draws the contours of these found pieces on the wall, so it sort of becomes a drawing or painting. What he finds, he evaluates, cuts down into pieces, and if there’s a salvageable piece that he likes and wants to work with, he puts it aside. Then there’s the onion. The onion represents the living element – the person behind the artist – who needs to be sustained through heat, through food, and all of these things. And the heat symbolises the primary needs being met.

Oto’s there every day, and he spends the day making a new sculpture. We have this exhibition edition – a new initiative we started with Katrīna Biksone’s show in the summer of 2025. We’re trying to find ways to generate a little more income for the artist, but also to create value for the visitor – for people who would love to have, for example, a Liga Spunde’s work in their home but can’t afford the thousand euros to buy one. Most of the people who appreciate her work are also artists, and many don’t have a large budget to spend on art.

We think it’s important for people to be encouraged to collect – or at least to collect what they like. So it’s a little bit of a “gateway drug,” you know? For under €100, we have ten works you can choose from – a series that the artist has made especially for this exhibition. In this case, Oto is literally making ten new works, which are the exhibition edition. These works are actually almost outside of the main exhibition. The main exhibition is centered around the idea of the process-driven work – and it’s happening inside and around the “totally white cube” of the house on the chassis.

Oto Holgers Ozoliņš. Artifacts of Process. 2026. Photo: Dāvis Drēziņš

And Oto is there himself – “The Artist is Present,” so to say.

He's there every day.

Is he also talking with people?

Yes. It really helps to understand the idea that there’s a process – and the process is happening inside the space. Over the five weeks that it will be taking place, it will change. It’s dynamic. So it really helps to understand that you can come back and see the process develop.

And if Oto isn’t there, one of us will be – we always make sure there’s a mediator to help people access the ideas behind the work. Often, when you see a show, you kind of get it, but it’s always nice to have a little background or to be able to have a conversation about it. What do you see? How do you see it as a challenge? How do you communicate the work?

I don’t know if the work should automatically communicate the ideas, but I think it should invite you in – make you want to know more about it. I think that’s maybe a better function of the work, especially when it’s complex and multilayered. It should be inviting enough to make you think, okay, what’s happening here? I really want to know more. Give me the text, I want to read it, or I need to ask someone a question. And I think that’s definitely happening.

For one thing, it’s nice and warm in there, so it’s literally creating a warm environment for someone to take the time to really see what’s happening. And I think there’s a lot of information there that you can maybe piece together.

Oto Holgers Ozoliņš. Artifacts of Process. 2026. Photo: Dāvis Drēziņš

Talking about process-driven work – I think TUR, as a place and as a project, is also very process-driven, because it’s so different with every exhibition. It’s also a very different space in summer and in winter. It’s very connected with what’s going on around – in nature, in the weather, in everything.

Yeah, it’s really essential. There are three solo shows in the winter and three in the summer – that’s the format. And we try to connect the three shows. It’s not essential – we don’t invite an artist based on, you know, oh, what theme are you working with? Or we need you to work with this kind of theme. But generally, we find that there is a connection. This cycle will be very much about shelter and conditions. Krišs Salmanis, our next artist, will also work with similar ideas, and Krišjānis Beļavskis will build something similar.

And the connection to the season is quite important, because – if you’re going to engage with the space, and this is something we ask – winter TUR is very different from summer TUR.

In winter, there is no heating in the big space, so there’s this survival element.

Survival, exactly. It’s tough, it’s difficult. And whereas maybe you’d expect people to think, oh, I’d like to have a show in the summer because it’s open, warm, and comfortable, a lot of artists actually want the winter space because of the conditions. They like that it’s cold and that it’s a little bit serious – yeah, no messing around.

I really like that the shows in winter have a very different identity from the shows in summer. Summer shows are much more open. Of course, they’re warmer. The light is very different, and light is a very important aspect. We have wonderful light coming in around six or seven in the summer. In the winter, it’s very different, but we actually have beautiful light now as well, especially with this gorgeous winter weather.

I love the winter, but I also love the summer. And towards the end of the winter, you’re so excited for spring to come. It’s like, ready for spring. Not because I hate the winter – it’s just like, okay, we’ve had a couple of months of this, now it’s time for a little change.

Līga Spunde. Field of Exercises. Installation view. 2025

I just thought that it could be interesting to make this kind of, you know, time-lapse film, where every exhibition is maybe just five to seven seconds, and then to make a one-minute video from all the exhibitions. How it could look… that would really be the portrait of this process.

Yeah, absolutely. I love it. I love it when the space is so different, and people are just like, what did you do this time? I remember at one point, one of our producers came in and thought she was in the wrong place, because the space had changed so much. And I loved that reaction. I really want people to come back just to see – what have we done this time, and how have we transformed it?

I think our artists also see that as a challenge. How can I make TUR different from what’s been done in this space before? How can I bring my work – but also my voice – in a way that hasn’t been done yet in this weird space? I really liked Kristīne Daukste’s approach in that sense, where the work kind of came from the floor, as opposed to coming from the walls or the ceiling. The floor became a kind of canvas that she was working with.

And sometimes we also leave some works, like we have still Reinis Dzudzilo’s little “exit” sign in gold up on the top. We do that because we feel like each exhibition makes its mark in the space. And sometimes it's a little bit more obvious than other times, but we leave certain little “Easter eggs” there for people to discover because, yeah, that moment in time and space has impacted it. And for us to completely wipe it away and act like it was not there feels disingenuous. It was there. It was part of the space. It made its mark. Look, if it's really necessary that it is wiped away, we wipe it away. We colour it. But you will find little memories of different exhibitions there to be found. I really like that about TUR.

Reinis Dzudzilo .ONE WILL HEART ONE. Installation view. 2024 Photo: Kristīne Madjare

You mentioned Reinis Dzudzilo’s exhibition. I also thought that sometimes you don’t need so many objects – the sound can also transform the space very radically. In his case, it was like some kind of church, even.

Absolutely. Each artist brings their own perspective on the space – how they feel about it and what they see when they enter. You start to look at the space in a very different way based on how things are placed there. Often, leaving things out can enhance the space.

For my exhibition, there was nothing in the space except two performers – just two older men who were dancers, performing a score each day we were open. And that was it. There were six choreographic maps on the wall, but they were really in the corner and were part of the performative work. For the rest, the space was empty.

Dzelde Mierkalne. Doom Doom Delight. Installation view. 2024. Photo: Kristīne Madjare.

Luīze Rukšāne,.Folding Lines. Installation view. 2024. Photo: Kristīne Madjare.

Kaspars Groševs. Café de Paris.Installation view. 2024. Photo: Kristīne Madjare.

Kaspars Groševs. Café de Paris. Installation view. 2024. Photo: Kristīne Madjare.

Your work in the TUR space was the starting point of a process that has brought you to this moment – now, in January 2026, you’ve been nominated for the Latvian Annual Art Award as Curator of the Year. How do you feel about being a candidate for this prize?

I was very surprised. But, yeah – I see it as a recognition of what we as a team at TUR do, because you can never do it alone, but also the quality of the artists and the conversations. And of course, it’s very nice to be recognised.

Sometimes it feels difficult, and you’re a little on the fringe as a non-Latvian artist. I think, again, where I come from, it’s very normal. I believe at least 75% of funded artists aren’t originally Dutch, but they live and work in the Netherlands and contribute to the scene. So, yes – it’s always been my goal to find a way to contribute and to bring something to the scene that might not be happening yet, or to supplement it somehow. And we do it with integrity and with a lot of love for Latvia, for Riga, and for the artists we get to work with.

Eric Giraudet de Boudemange, Agnieszka Polska, Līga Spunde,

Agate Tūna. Under the Sun. Installation view. 2025. Photo: Bob Demper

It’s quite meaningful that, as a curator, you don’t have a traditional curatorial background – you come from an entirely artistic background. You completed the Art Science Department at the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague in 2005. But after that, most of your work was in choreographic and art projects…

I’m an artist, and that’s how I approach projects. So, it’s not academic. Obviously, I’ll read up on different themes, if necessary, but for me, it’s more about supporting the artist in their perspective and what they’re looking to communicate or bring into the space. How can you turn their interesting work into a great exhibition? There’s still a step to be made there, and not every artist knows how to translate their work into an engaging exhibition. That’s where the challenge lies – how can you take to a new level?

But sometimes it’s also about just facilitating basic needs. Maija Kurševa is a very good example – she doesn’t need that much conversation when developing her work for an exhibition. It’s nice to have a conversation with her, but she knows what she wants and what she’s doing. As a curator, the key is just to make sure she has everything she needs and let her get on with her work.

Then there are other artists who really want to have that conversation. I think with Oto, for instance, that was the case. We had really long, interesting coffees where we talked about the work and how we could bring it into the space.

Oto Holgers Ozoliņš. Artifacts of Process. 2026. Photo: Dāvis Drēziņš

And this kind of curatorial approach works perfectly with solo shows – and that’s actually what TUR is about. But you have a new mission: you’re the curator for the next exhibition at Zuzeum Art Museum, “Collections,” which will open in February. There will be many artists, very different works, and very different media. How are you managing this?

Yeah, that’s in less than a month, so most of the work is already done. And it’s true – it was a really, really challenging process for that reason. First of all, you’re working with artworks that are already made and are part of a very large collection, to which you don’t have immediate access. So you’re working from a database, from pictures on a screen. How to approach that was really challenging.

I thought again about what I wanted to offer the visitor. I wanted it to be very accessible to as wide a range of visitors as possible. I think Zuzeum is a wonderful place for people to take their first steps into exploring contemporary art and experiencing it. So I don’t want to scare them away. I want them to have a space where they really feel enriched.

We have more than 200 works that we’ve selected from all periods, from all aspects of Zuzeum’s collection. It’s really about – again – taking it from an artistic perspective and turning it into some kind of installation. In working with these works, we’ve clustered them. I say we because I’ve worked very closely with Andris Kaļiņins, who’s doing the scenography. We cluster the works based on different themes or tropes, letting people see that there are similarities in different works, but that each work is unique.

There’s a term I coined for this – generification – where, in our culture, it seems that everything is becoming increasingly grey. Everything is sort of homogenised to serve as wide a market as possible, and individuality is seeping out. The colour is seeping out – of our products, of our lives. Movies need to do well in China, in Brazil, and in the UK. So they kind of create something that nobody will find offensive, nobody will love, but nobody will hate. And it’s kind of like that when you look around – the colour of cars has changed. I think the colour of the year this year is white, which isn’t technically a colour. So the arts are kind of the last bastion where things cannot be generic. It’s always created by an individual’s creativity. It’s always a subjective expression.

And that’s so important – so valuable – because difference is really important in our society. We need to embrace our differences. I think with this sort of generification, everything is becoming kind of the same. This appreciation of difference has eroded, and we want to celebrate it a little by showing, for example, five or six works about the sun. Each one is very different, yet they’re all about the sun. And that might be a very obvious example, but there are also much more subtle things. Often, works and clusters can also relate to other works and clusters in the show.

And I like to show that a work by an artist from a hundred years ago can live next to the work of a contemporary artist. So there are a lot of contemporary artists in this exhibition, as well as the – you know – greats. The greats are there too.

This exhibition is also, in a way, a little homage to the collection and to the fact that there are collectors – people who collect. The show is called “Collections” in that sense: we all collect, you know. You can collect ideas and inspirations.

The show opens with several works related to elephants, because as a kid I was collecting elephants, and one of the collection keepers is also collecting elephants. This is something that got me interested in bringing things together and thinking creatively about objects – things you can have and place in the space. And it could very well be that having a collection is the first step in creating something.