There is no single truth

Review of the Abstraction as an Open Experiment exhibition at the Tallinn Art Hall

25/10/2018

It has long been no secret that the 20th century was one of the most exciting and rapidly changing periods in the global art history. Over the course of roughly a hundred years, the art life underwent radical changes, from impressionism and symbolism to land art, feminist art and even forms of digital art, crossing the boundaries of some 40 forms of artistic expression in all (the number refers to the most popular styles only) and performing a giant leap in its development. It is another ‘universally acknowledged fact’, of course, and it may seem superfluous to repeat it. And yet ‒ repetitio est mater studiorum, and revisiting well-known things is often worth one’s while if the context of the reason behind this interest has changed. In this case, a reassessment of the ‘magnificent century’ is inspired by exhibition ‘Abstraction as an Open Experiment’ on view at the Tallinn Art Hall (Tallinn Kunstihoone) though 4 November 2018.

A happening at the former airfield in Lasnamäe, Tallinn. 1974. Photo: Jüri Okas

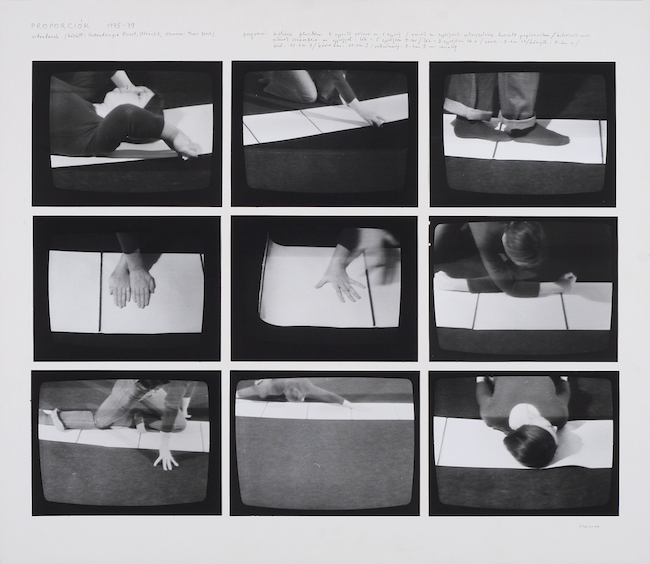

Dóra Maurer. Proportions, 1979. Photo: Miklos Sulyok

Since the early 1900s, abstraction has been one of the main forms of the modern language of art; as suggested by the title, it has also taken the spotlight at this particular show. In the contemporary lexicon, the terms ‘abstraction’ and ‘abstractionism’ are used quite freely, often referring to phenomena that are hard to link with natural, self-evident content and form. To a certain extent, it also reflects the criteria of cultural, artistic, sartorial, social etc. values espoused by the contemporary Homo Sapiens: the context of each specific phenomenon does not necessarily need to be glaringly obvious as it may be mistakenly perceived as a veiled insult to the person’s intelligence. Another correct interpretation of the term ‘abstraction’ dates back to 14th-century French where it is defined as renunciation of all things worldly or asceticism. And yet it is hard to imagine that in art, where ‘abstraction’ is a tentative description and its trends are embodied by a number of avant-garde movements, it would be possible to limit oneself to an interpretation of ‘abstract’ as ‘ascetic’.

Sirje Runge. Proposal for the Design of Areas in Central Tallinn, 1975. Photo: Auguste Petre

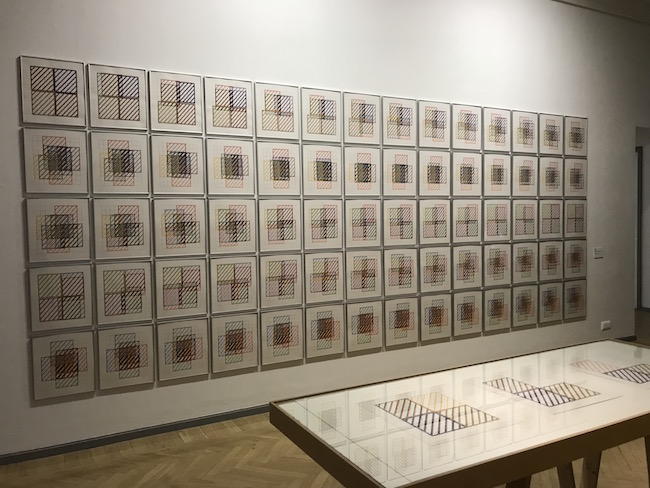

Dora Maurer. Displacements, 1972-1982. Photo: Auguste Petre

,%202008.%20Photo%20Croy%20Nielsen.jpg)

Falke Pisano and Benoît Maire. Organon (and the audience perception), 2008. Photo: Croy Nielsen

It is perhaps for this reason that the exhibition on view at one of the main art spaces in Tallinn since mid-September presents abstraction in the form of an open experiment. Four female artists of different generations and nationalities ‒ Sirje Runge (Estonia, 1950), Zofia Kulik (Poland, 1947), Dóra Maurer (Hungary, 1937) and Falke Pisano, (the Netherlands, 1978) are represented at the exhibition. They are joined by three gentlemen ‒ Przemysław Kwiek, Benoît Maire and Jüri Okas ‒ as the co-authors of selected works.

Sirje Runge. Space I, 1977. Photo: Auguste Petre

The exhibition as a whole is centred around the Estonian artist Sirje Runge and her early art. The 1970s saw this influential painter and designer and a group of similarly minded fellow artists dedicate themselves to exploring the traditions of the local geometric abstractionism, focusing on restoration of the artistic legacy of the 1920s Group of Estonian Artists (Eesti Kunstnikkude Rühm). Unsurprisingly, this special interest in colour, form and legacy of the past evolved into a certain protest against the official Soviet art, the school of socialist realism. Clearly Runge’s art does not in any way conform to this somewhat ambivalent artistic ideology imposed on every creative person in the Soviet Union at the time. While the main definition of socialist realism ‒ ‘socialistic in content and national in form’ ‒ was never explicitly elaborated, any attempts to interpret in a more relaxed manner were also forbidden, which makes the presence of abstractionism in this kind of atmosphere truly unbelievable. A phenomenon that seems intriguing in the context of the development of Estonian art is the interest of a number of artists (including Runge) in Pop Art in the 1970s when trends of the ‘low-brow’ mass culture were transformed into an elitist art form as part of the so-called Soviet Pop. Why is it important to mention this when speaking of the exhibition ‘Abstraction as an Open Experiment’? As I said earlier, while neither abstractionism nor 20th-century art history are unfamiliar or unexplored areas, the emergence of ‘pure’ geometric abstraction in the context of Soviet art is a most unusual phenomenon. It may be recognisable to an Estonian viewer; to any other visitor insufficiently well-versed in the history of Soviet art, the curator of the exhibition Maari Laanemets has left this connection unexplained.

Sirje Runge, Space II, 1977. Photo: Auguste Petre

.jpg)

Zofia Kulik. Legnica/Working Chimney, 1971 (2018). Photo: Auguste Petre

The featured works by Sirje Runge range from surreal pencil drawings to studies/paintings of Pärnu kindergarten buildings and playgrounds and images of other architectural forms. Special attention should be paid to the ‘Geometry’ and ‘Space’ painting series in which the artist uses pure form and colour to create a sense of presence somewhat detached from reality and identity. A similar mood defines the works of the other artists, for instance, the 1919 black-and-white video ‘Proportions’ by Dóra Maurer that captures repetitive strings of simple actions, or the ‘Legnica’ (1971/2018) series of photography prints by Zofia Kulik.

Sirje Runge. Space III, 1977. Photo: Auguste Petre

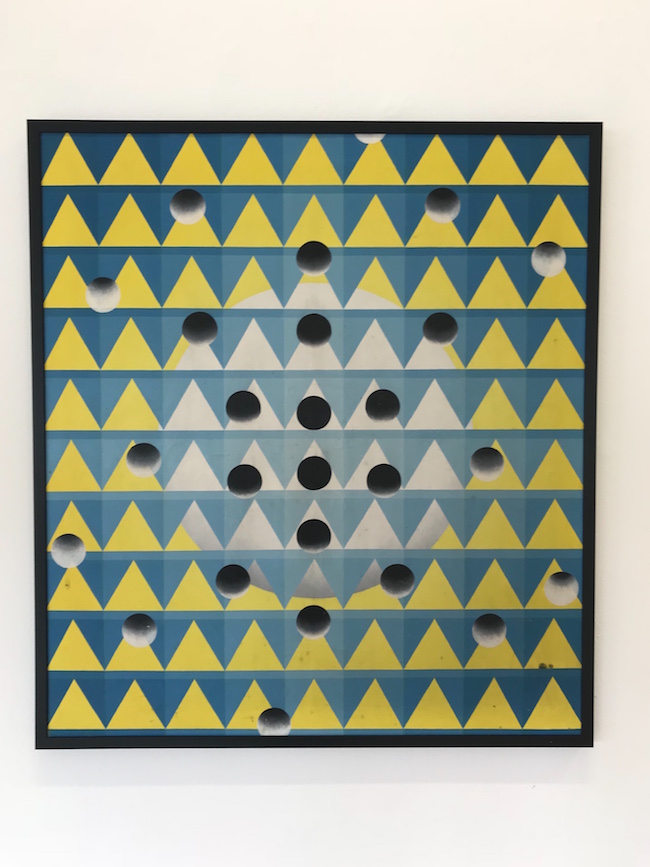

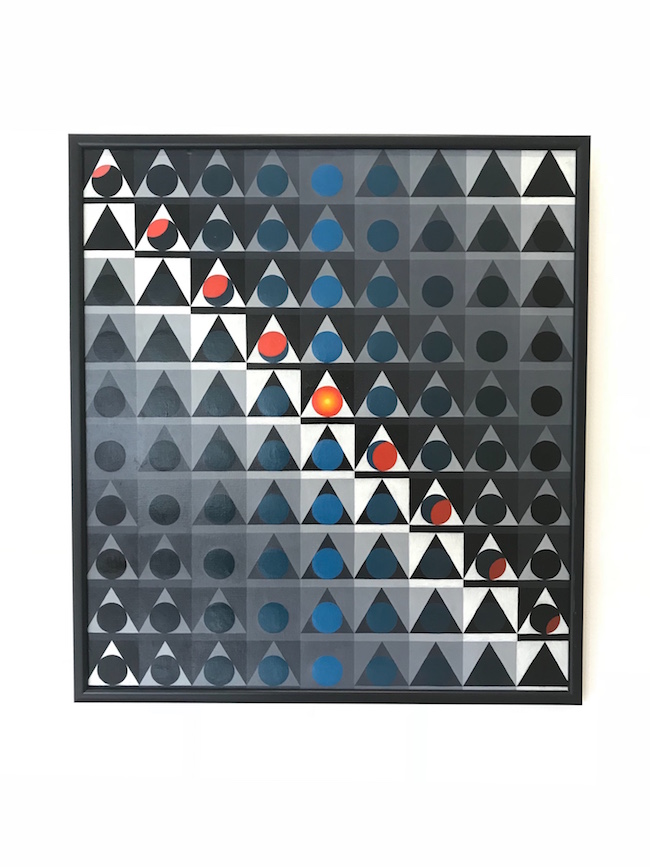

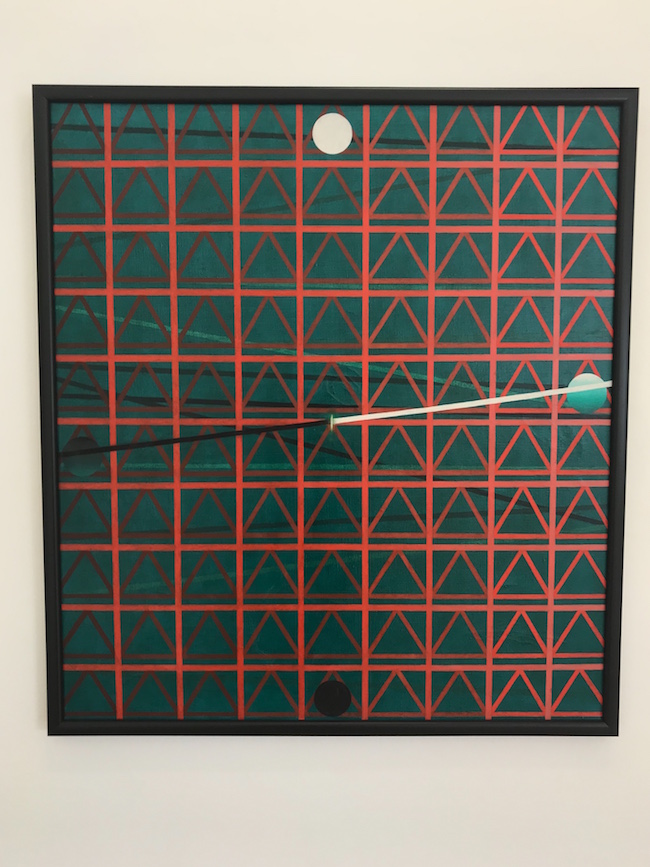

In her ‘Geometry’ cycle (1976‒1977), Runge focuses on depiction of primary geometric forms and methods of constructive painting, highlighting analysis of means of expression and the working process as the super-subject of the series. In these vividly colour-schemed oil paintings the artist explores combinations of perfect geometric forms, often ‒ triangles. Colour is assigned a dominant role, and the effect created by using smoothly textured expanses is almost poster-like (hence ‒ active). Similarly to her ‘Space’ (1977‒1978) series, Sirje Runge is playing with ‘rational abstractionism’ here, sometimes bringing to mind suprematism but most of all ‒ neo-plasticism and the so-called hard-edge school of painting. These are, of course, simple comparisons born somewhere along the winding path of visual consciousness, and yet it seems hardly coincidental that Californian hard-edge painting was influenced by geometric abstractionism as well as contributed to the development of conceptual and minimalist art. There is also a hint of indirect influence by op art in the paintings of the ‘Space’ series, the difference being that, with her repetitions of geometric forms and colour contrasts, Sirje Runge has not so much attempted to create an optical illusion as explore the boundaries of a new (perhaps super-real) space or existence. The element of composition uniting these works is the exact square-like division, which may seem merely an aesthetic touch at first glance but opens up wider fields of interpretation on further inspection. In each of the little ‘squares’ a number of miniature geometric forms come together, becoming a separate structure ‒ a tiny something that is a part of something bigger. The idea resonates with Maurer’s phase-like drawings of the ‘Displacement’ series, although they are essentially akin to the op art approach. In all, the work comprises 70 framed drawings in which the artist experiments with variations of shifting layers of colour. One by one, each field of a different colour is shifted from left to right, horizontally, vertically or diagonally. As the shifts intersect and overlap, a surprising spatial effect is created. Compatibility of dimensions is also explored in the largest piece featured in the exhibition, Falke Pisano and Benoît Maire’s installation ‘Organon (And the Audience Perception)” (2008). Through the irregularly shaped tables and the ‘objects’ or compositions of various materials placed on them, the subject of a creative dialogue is explored, underscoring the general theme of the whole exhibition.

Sirje Runge. Works from serie "Geometry", 1976. Photo: Auguste Petre

In her notes on the exhibition, the curator points out that one of the keywords of this project is openness ‒ an idea that developed in the 1960s as a radical counter force to the authoritarianism of modernism. The theory of openness in the context of exhibition ‘Abstraction as an Open Experiment’ can also be viewed as the experimentalism of individuality. An abstraction revealed by a human personality.

,%201975.JPG)