On T-shirts, but not exclusively

Maria Helen Känd

Photos: Paul Kuimet, Tallinna Kunstihoone

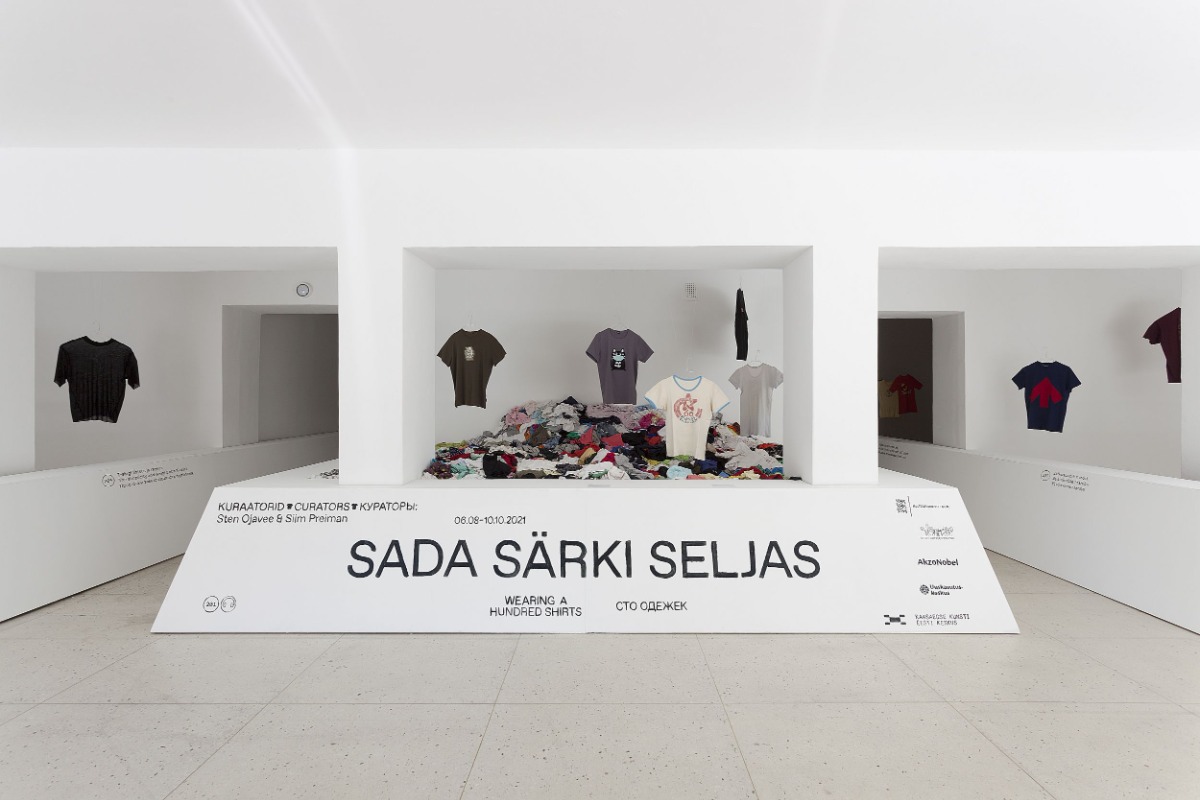

The exhibition “Wearing a Hundred Shirts”, at Tallinn Art Hall

Upon entering Tallinn Art Hall Gallery’s new exhibition “Wearing a Hundred Shirts”, visitors are faced with a counter for clothes that, as to expected from the name, is piled with T-shirts (recycled ones, fortunately). Why T-shirts, and what do they have to do with art? One possible answer is given by Siim Preiman and Sten Ojavee, the curators of this exhibition that looks beyond the fashion and consumer value of T-shirts, and which has been divided into shirt-chapters.

Ironically, but maybe not intentionally, the title of the exhibition could be considered a namesake of shows that took place as part of the EV100 celebrations (the 100th birthday of the Republic of Estonia). Furthermore, the presented T-shirts narrate the history of key events that have taken place in the last 100 years of Estonian history, highlighting the fashion statements of different eras. Even if shirts are at the heart of the exhibition, a design experience is not its main aim – seeing as the curators view shirts as carriers and conveyors of one’s identity, in this case it’s the social perspective of T-shirts that is more prevalent and exciting.

One of the good features of this exhibition is the recognizable signature style of its two curators. Ojavee has previously focused on the intersections between art, fashion, and culture, such as in the 2018 Artishok Biennale project. In this current project he elaborates on the background of the fashion market and its brands, as well as introduces the work of designers (with his local favourites,[1] such as Laivi’s shirt, among them).

Preiman’s curatorial position has an environmental agenda, and his focus has been on researching topics that look towards a more equal society. These themes are reflected in the shirts of political environmentalists (“Nuclear plant? Today? No!”), as well as in shirts by Kertu Ehala and Ave Teeääre, which have a feminist message and are socially critical, but still evoke comic relief.

A pile of T-shirts and T1

The societal aspect of T-shirts is, without a doubt, expressed in both their consumption and ecological footprint. It can take up to 2,700 to 5,800 litres of water to produce one cotton T-shirt. The container standing in the middle of the gallery and filled with piles of shirts represents the hundreds of thousands of T-shirts that end up in places like the Ghanaian landfill.

The minimalistic exhibition – set up in the white-walled space without any banners or signs – has only a few samples of T-shirts hung up and reminds one of a closed clothing store. The so-called “dead malls” or “ghost malls” in the United States are one of the most striking examples of consumerism and capitalist absurdity, a phenomenon that has manifested locally with the bankruptcy of the shopping complex T1. Consequently, it is quite possible that the curators were aiming for a similar atmosphere and meaningful intent.

The exhibited “Up-shirt” by Reet Aus illustrates more directly the problems and possibilities of contemporary production methodology. Aus’s shirts have become such a canonical trademark of Estonian environmental design that a T-shirt exhibition without one of his shirts is unimaginable – to the point of being predictable.

In addition, Marat – the oldest and still operational Estonian apparel brand – has been well introduced by the curators. However, the sad irony is that many Marat buyers nowadays do not know that the clothes of this fierce Estonian retro brand are produced in Belarus, where the average monthly salary in the textile industry is less than €200 per month. Moreover, we all have been witnessing the ongoing human right violations in the country.

T-shirts instead of posters

T-shirts communicate in the language of cultural signs and are comprehensible to many, but sometimes they are specific jokes for an inner circle. Mart Laar, historian and former Prime Minister of Estonia, once called the wearers of the ubiquitous Che Guevara shirt “useful idiots”; similar feelings may strike when one sees Kim Kardashian wearing a symbolic sickle and hammer, a sweater designed by Gosha Rubchinskiy. Ignorance does not absolve the wearer from responsibility of the contextuality of one’s clothes. (Pop) culture and fashion design are thus an inseparable pair, like the brothers Cain and Abel from the Bible – one may knock the other down, but he will still be trapped in the semiotic circle of brotherhood.

Without directly selecting sides, the curators have put out both peculiar and less-peculiar examples of T-shirts that carry loaded messages and symbols from Estonian history. There are shirts that demonstrate the political and opposing potential of this form of apparel, like the scandalous “Commies to oven” shirt from 2005 and the “Ours in Russia” shirt from the 2007 Bronze Night upheaval. These encounters bring back a bygone era that was close to the skin, launching the viewer on a bittersweet walk in the Estonia of the 00s .

However, the question arises as to why the curators decided to create these specific thematic chapters, because some of them – such as “Environmentalism”, “Sustainable fashion” and “Solidarity as a protest” – seem to overlap to a notable degree. Secondly: why are there only a few items put out as key works on each topic? Poignant additions, for example, could have been the shirt by SALK, a civil liberalist movement that put the face of Henn Põlluaas, a former Head of Parliament and right-wing party representative, on a T-shirt. Similarly, a plant-painted shirt by the artist Sandra Kosorotova would have convincingly fit into the categories “Art shirts”, “DIY”, or “Sustainable fashion”. Even though laconically designed exhibitions often allure, one may still feel the desire to flip through more examples – artistic design shirts, protest shirts, shirts with ironic messages, and so on. One may find the maniacal consumerist voice in oneself say: less is not always more. If you want to go all in, do it with a T-shirt show.

Despite the fascinating historical finds, the Art Hall Gallery had a somewhat empty and cold ambience. The shirts in the pile were there to be touched or even to be tried on, but in the twilight (the lights have been turned off so as to protect the objects that belong to museum collections) and in a rather modestly designed space, the individual T-shirts did not come to life. As a result of socio-analytical deconstruction, it wasn’t easy to imagine these shirts worn by bodies made of flesh and bone. Perhaps the shirts could have used additional videos or photo documentation – for example, of political protests in Estonia. In this sense, however, the curators stayed firm to their confident and dignified position – let each T-shirt speak for itself.

[1] The radio show where Ojavee brings out Laivi as one of his favourite local designers https://idaidaida.net/et/jarelkuulamine/materialism-kulas-sten-ojavee-13-02-19