The fifth Kochi-Muziris Biennale is about to open

23 December 2022 sees the opening of the key exhibitions at Kochi-Muziris Biennale, the biggest art event in South-East Asia.

Situated on the Malabar Coast of the Arabian Sea, the Indian city of Kochi (or Cochin) has always been (under various names) a hub for exchange of goods and ideas. This, until the fourteenth century, was the location of the legendary port city of Muziris that was then swept away by a huge flood. It was then that the actual Kochi was built, a cosmopolitan port city, quite large for its time. Control over it was first seized by the Portuguese (their settlement was founded in 1500, and it was in Kochi that Vasco da Gama was first buried; his remains were later moved to Portugal). Then, in the seventeenth century, they were driven away by the Dutch who, in their turn, lost this place to the British.

View of the Aspinwall House complex from the sea. Photo: Kochi Biennale Foundation

Spice trade was a very profitable business back then, and the city was filled with warehouses and offices of companies and family clans dealing in it. However, times and priorities changed. These numerous buildings have now been abandoned or are currently living a ‘life after life’ of some kind, including as art spaces. Founded in 2011, the Kochi Biennale (incorporating into its name a reference to Muziris, the city that had been swallowed by historical oblivion) soon evolved into the largest contemporary art event not just in India but the whole South-East Asian region.

Preparatory works in the courtyard of the Aspinwall House

In 2019, Shubigi Rao, a Singaporean artist and writer of Indian descent, was chosen as the curator of the upcoming edition. And the biennale was scheduled to open in December 2020. But all plans were thwarted by the pandemic: as winter approached, it had the state of Kerala firmly in its grip; the biennale was cancelled, and the plans were revisited only in 2022. This forced pause, however, took a substantial toll on the actual institutional structure of the biennale and on its capacities. The belatedly received funds from the state; the disbanded and reassembled team; problems with the principal venues of the biennale – the Aspinwall House compound of buildings, also Pepper House and Anand Warehouse (including hole-ridden roofs and streams of water unexpectedly descending on freshly installed works)… All this led to a situation where late on 12 December 2022, that is, a day before the scheduled official opening, it was postponed by ten days. The decision was made after a meeting with dozens of extremely angry artists, incensed by countless organisational blunders; apparently, Kochi Biennale historically had always battled with this kind of problems but this year the level had skyrocketed.

This is what the already exhibited works looked like on December 16, hidden under the film

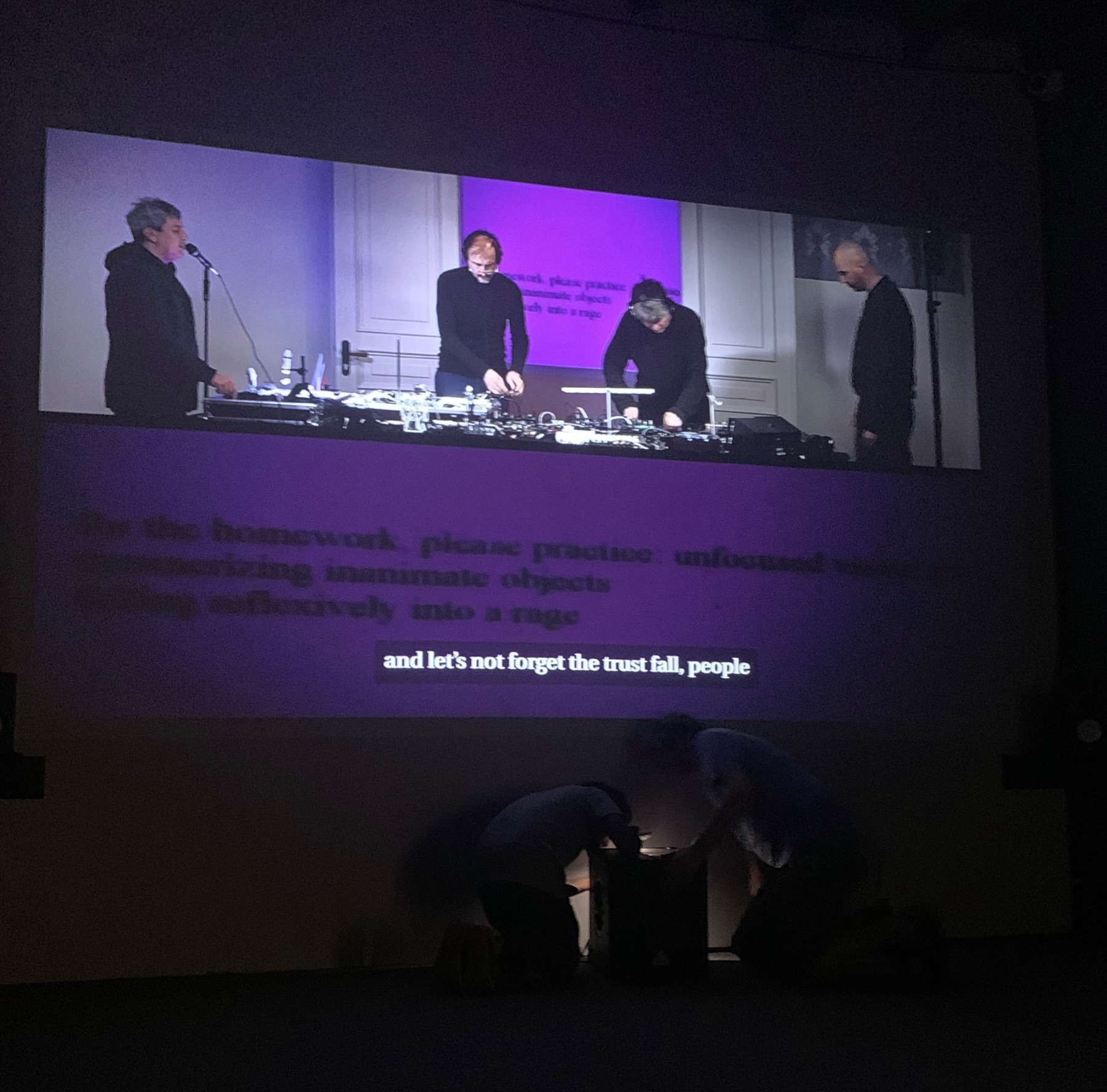

Following this decision, all the works, even the ones that had already been installed (mostly paintings, prints or photographs), were wrapped or covered with plastic, almost completely obscuring any hints of their shape and content. The assemblage and setting up of the rest – installations, video projections and so on – were switched to a regime of permanent feverish activity. I speak of it from my own experience. Back in 2019, Shubigi Rao invited the Latvian Orbita group of artists and poets to take part in the biennale. As a member of the group, I arrived in Kochi on 9 December; initially we were supposed to present a performance using various local materials that we intended to find in the streets of the city, as well as our new video, a film entitled ‘Motopoesis’. The performance was cancelled due to postponement of the opening date, and we only managed to finish setting up the video projection – part of the exhibition at Aspinwall House – a few hours before our flight home on 17 December. You would think it was ever so simple: all you need is a video projector, a media player and a sound system. For the first few days, whenever we visited our space, we only encountered local workers who had chosen this dark back room deep inside Aspinwall House as a place for rest: someone was always either asleep here or spending time horizontally while scrolling their phone. Endless negotiations with technicians and production managers did help us make some progress, albeit a very slow one. Perhaps it was exactly because the majority of problems people were having with the installation process were getting solved simultaneously: the artists snatched somebody or other from the organisers’ team and buried them under the load of their current requirements. The poor devils tried to start solving said issues, at which point they were immediately abducted by other artists whose problems were even more urgent and glaring…

Taming the subwoofer in the Orbit room at the Aspinwall House. Projection – movie 'Motopoiesis' (2022)

An enormous load of responsibility in this situation landed on the shoulders of the curator Shubigi Rao, despite the fact that she was the one person who had done her work in a timely fashion: she had come up with a concept under the motto ‘In Our Veins Flow Ink and Fire’, chosen some 90 participating artists and commissioned more than 40 new works for the biennale. And yet she was forced to spend the last few weeks prior to the opening practically without leaving the construction site dust-filled buildings undergoing endless renovation. She had to make multiple visits to the hospital for a lung and ear infection as a result of that. The curator was also absolutely the last person who the participating artists blamed, well aware as we were that pushing the builders and making sure they had been paid for their work was not really her job.

One of the most interesting satellite projects is an excursion into the past of the Tibetan resistance to Chinese occupation. Ritu Sarin refers to the archive of his father, who was the secret leader of the Tibetan guerrillas - they were supported by the CIA in the 50s and 60s. Ritu Sarin was preparing the project with her husband, filmmaker Tenzing Sonam. The exhibition is titled 'Shadow Circus: A Personal Archive of Tibetan Resistance (1957–1974)'

‘But once the biennale opens, everybody will see that it is wonderful,’ we were assured over our morning coffee by the California-based collector of contemporary Indian art Asha Jadeja Motwani who meticulously explored all the venues where she took furtive peeks under the plastic sheets covering the works. ‘A biennale can be so much more than a mere accumulation of coincidental collisions. As a bulwark against despair the biennale as commons may seem an impossible idea. But we remember the ability of our species, our communities, to flourish artistically even in fraught and dire situations, with a refusal in the face of disillusionment to disavow our poetry, our languages, our art and music, our optimism and humour. To envision this biennale as a persistent yet unpredictable murmuration in the face of capriciousness and volatility comes from my unshakeable conviction in the power of storytelling as strategy, of the transgressive potency of ink, and transformative fire of satire and humour,’ it says in the curatorial statement. The fifth edition of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale promises to be poetic and philosophical and task itself with examining a diverse range of human stories – predominantly stories from South-East Asia, of course.

The TKM Warehouse building complex, which houses seven satellite projects of the Biennale

Because it is, of course, first and foremost a regional project, an opportunity for artists from Bangladesh and Singapore, Nepal, Indonesia, India, Thailand and other countries to meet and get a sense of the shared context, the shared range of problems.

On the final night of our stay in India, Shubigi tore herself away from her endless organizational worries to join us for a conversation in the Orbita room where we were awaiting the final word from the technicians (who were busy connecting a subwoofer to the loudspeakers in some very complicated way, soldering away under the very ceiling). We asked her about the way she saw the biennale that she had conceived four years ago and that was currently already taking shape before our very eyes, and she said: ‘For me one of the loveliest things [is that] I had this idea of how works would be speaking to each other in their proximity and that came out really well. So when you experience one work and you move to the next work, you don’t disconnect. Each work leads you somewhere else, it’s like a flow. And to me it’s really important and really beautiful because we don’t make works in the vacuum, we don’t write in the vacuum, we don’t exist in the vacuum.’

At the Student Biennale, also housed in old warehouses in Kochi

Asked about the poetic character of this edition of the biennale (it is, after all, ink and fire that ‘in our veins flow’, according to Shubigi), she told us: ‘It’s intentional. Because I’m also a writer after all. And for me the reason why art is so powerful is because language is a failure, language can’t tell you everything. There is no proper communication. And because we have gaps in our communication, we fill those gaps with poetry and music and art. And that’s why I think is important to look for poetry in unexpected places. And everyone has different poetics. So you have to leave space for the other people forms of poetry as well and I mean also poetry which exists without any words. I don’t know if this exhibition is very ‘instagrammable’ or really ‘bombastic’. To me it’s more about the reason to slow down, to take the time. This is the exhibition which took 4 years to make it. So I would like that people don’t just walk past things.’

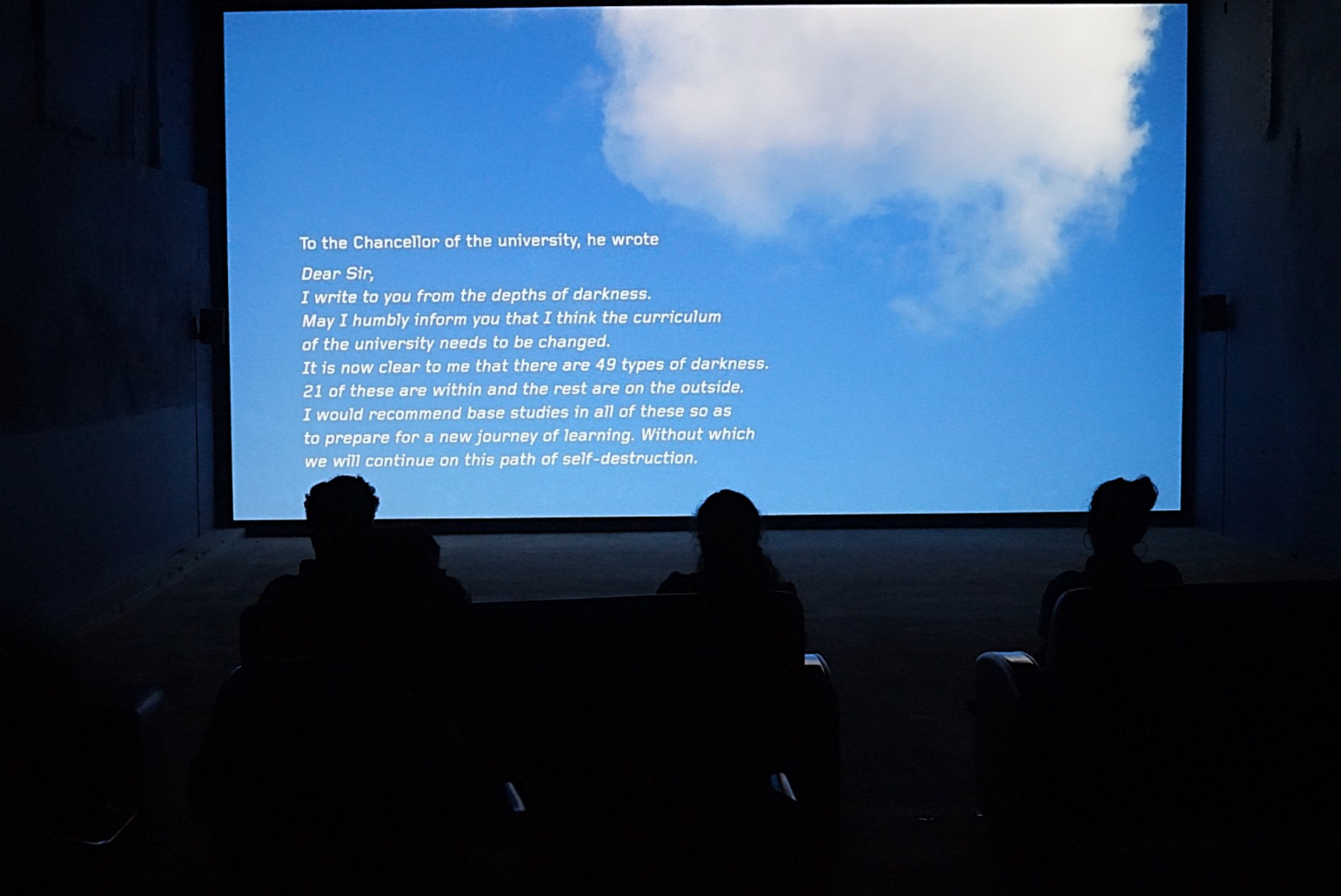

At Amar Kanwar's exhibition 'Such a Morning' at the Anand Warehouse

And it was exactly an experience of the sort referred to by Shubigi that the show by the Indian director and artist Amar Kanwar ‘Such a Morning’, presented in two enormous rooms at the Anand Warehouse, was for me: it is a film in which a professor of mathematics retires from the world and locks himself up in darkness to discover 49 shades of the dark, also an exhibition based on the professor’s letters to his students. ‘I had this feeling since around 2015 that, if you took a look around, many of the social and political systems were stalling; they did not offer any solutions. And it does not matter if the governments are liberal, leftist or right-wing ones. I had this feeling that I wanted to leave this illogical pattern. And it is exactly this that shaped the genesis of my film – this intent not to restart things that are around us but rather to prepare for an internal reboot, to restart the actual way we think. It seems to me that we need to take a step back to see the blind spots we keep not noticing.’ (Our conversation with Amar Kanwar will be published in full on Arterritory in late December.)

Amar Kanwar’s exhibition was already installed, although there was no accessible information about it anywhere, and people were dropping by all the time; it was largely the result of a timely decision made by Kanwar: he arrived in Kochi two months before the scheduled opening date and brought his own technical team.

My absolute favorite at the Student Biennale is artist Shiv Shankar and his 'Govar Toli' project

«Shiv Shankar recently completed a Bachelor of visual Arts at The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda in 2022. He dwells on the complexities and nuances of the Yadav community of Bihar, to which he belongs, as it continues to rise above the socio-economic and political barriers that disadvantaged the community based on the hierarchical system of caste structure»

«In the artist's telephonic conversations with his mother, community events and norms come up as frequent themes, leading the artist to re-imagine its imagery through paintings and image transfer by placing them into phone screens. The artist thus treats discarded phones as a canvas and a portal to display his societal connections»

13 December saw a string of other satellite projects open without a glitch; while presented under the umbrella of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, they were all mounted independently by various institutions and organisations. First, it was the Students’ Biennale that has taken over several buildings in the Mattancherry district of Kochi and serves as a platform for graduates and students of art colleges. It was followed by seven separate shows housed at the TKM Warehouse, one of which was William Kentridge’s ‘Oh to Believe in Another World’, a work visualising Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 10 in a manner characteristic of Kentridge’s art Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 10, featuring as its protagonists some well-known Soviet figures from the 1920s, from Mayakovsky and Lilya Brik to Stalin and Shostakovich himself. It is something like a Constructivist ballet staged as ‘post-archival animation’ with collage-like human figures as puppets. The video work premiered in summer at the London Goodman Gallery. Kentridge personally made an appearance in Kochi where he presented his performance ‘Ursonate’: accompanied by his animation and a group of local musicians, he delivered a brilliant rendering of Kurt Schwitters’ eponymous poem written in 1932, an example of Dadaist sound poem. Before the performance he gave a short talk and spoke of Dadaists as artists who had found themselves in a situation where the old logics and foundations no longer worked (resonating in some way with the words of Amar Kanwar).

A visitor in the hall with a video projection of Jittish Kallat. Photo: Vladimir Svetlov

Another noteworthy work among the projects on view at TKM Warehouse is the piece by the Indian artist Jitish Kallat, a video projection of a text in English on a wall of mist, constantly flowing and stratifying; it is a letter by Mahatma Gandhi to Adolf Hitler, written in 1939, a few weeks before the beginning of the war. Jitish is not just an artist but also a curator; it was in the latter role that he oversaw the Kochi Biennale in 2014. This time around, a group exhibition entitled ‘Tangled Hierarchy 2’ at self-same TKM Warehouse features a selection of works by considerably well-known artists hailing from a vast variety of locations, from Mona Khatum to Mykola Ridnyi. Ridnyi’s 2008 video ‘Seacoast’ is a footage of jellyfish falling to the ground on a beach in Odesa to a soundtrack of howling and blast of exploding bombs. This piece focusing on the speed with which military aggression can break out and spread in today’s world was made as a response to Russia invading Georgia – six years before the Russian annexation of Crimea and the hybrid war waged back in the artist’s native Ukraine.

A fragment of the exposition 'Bhumi'

An adjacent gallery at TKM Warehouse shows an exhibition titled ‘Bhumi’, a genuine example of collective authorship (which is also one of the key points of the concept behind the biennale). The project was initiated by several Bangladeshi art institutions during the outburst of the 2020 pandemic. In the north-west of Bangladesh, local artisans from four villages, left jobless due to the lockdown, joined forces with the artist Kamruzzaman Shadhin to create a whole separate world out of bamboo, jute and straws, a community of people and gods, a depiction of heaven and earth. This impressive array of figures has now moved to Kochi.

A fragment of the exposition of Prasanta Sahu at the Mocha Art Cafe

Presented in an exceptionally well-thought-out manner, a project by Prasanta Sahu, an artist from West Bengal, is another example of interaction between the worlds of contemporary art and traditional agriculture and crafts; it is housed in Mocha Art Cafe, a satellite venue for the biennale in the Jew Town district of Kochi. Over the span of three years, Sahu has tried to visualise using a diverse range of techniques the course of life and work of a landless farmer named Lakhmi Rans Khanda living near the place of residence of the artist himself. ‘I feel urban people are not sensitive enough to recognise, notice the contribution of rural India [..]. In my childhood days I remember the exchange/barter system where a cloth merchant would sell his clothes in exchange for rice from a household. In their system the scope of recognising the individual’s contribution is possible. In a post-industrial society with a highly developed trade, transportation, cooperatives etc., the producer and consumer remain completely unaware of and disconnected from each other,’ the artist observes. Plaster casts of vegetables, drawings of plants, maps with the geodata of fields make up an almost documentary story under the title ‘Anatomy of a Vegetable’.

Asim Waqif's work 'Improvise'. Photo and video: Vladimir Svetlov

Another work focusing on the plant world and its materials is the giant installation entitled ‘Improvise’ by Asim Waqif, an artist from New Delhi; his solo exhibition was on view at Palais de Tokyo in 2012, and he has long been interested in transforming rubbish, scraps and other stuff that costs nothing into large-scale art objects. The installation is built of various kinds of bamboo, coir fibre, pandan leaves and other things. The twisted vortex-like structure that has appeared in the yard of Aspinwall House seems to be about to uncoil and shoot up into the sky. As for Waqif, the creator of this piece, central for the biennale, he has voiced sharp criticism of the leadership of the Kochi Biennale Foundation and the technical team of organizers and was one of the initiators of the artists’ efforts of self-organisation and defending their rights.

Scottish artist Jim Lambie has transformed the space of another venue for the Biennale - David Hall

Understandably so. The Kochi-Muziris Biennale is extremely important for the artists of India and the whole region. Mistakes of the fifth edition must be recognised and corrected to prevent future editions from encountering equally critical and hopeless situations. Meanwhile, we can only guess how the upcoming biennale, expected to run from 23 December 2022 through mid-April 2023, will actually turn out. The butterfly is yet to emerge from the cocoon covered in construction site dust.

Title image: Amar Kanwar's exhibition 'Such a Morning' at the Anand Warehouse. Photo: Vladimir Svetlov