A Forum for the Indigenous

Notes after visiting the 60th Venice Biennale

I read the first reviews of the 60th Venice Biennale while flying home from Venice. They all discuss how one should comprehend the Biennale’s main exhibition, Foreigners Everywhere, curated by Adriano Pedrosa, which at its deepest core, is about foreigners (the viewers, mostly representing the Western art scene and cultural outlook) meeting other foreigners (artists from the so-called Global South and Asia, indigenous peoples, queers, and other minorities), who in no way fit into the existing and familiar context of the Western art scene, and whose names are unfamiliar to the majority of the Biennale’s classical audience.

Works by Aycoobo (Wilson Rodríguez). Photo: Matteo de Mayda / Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

As J.J. Charlesworth writes in ArtReview (60th Biennale Review:Who Can Judge?): ‘In front of the bright acrylic-on-paper psychedelism of Colombian artist Aycoobo, whose intricate and dazzling paintings elaborate on the worldview of the Nonuya people, a culture whose cosmogeny and origin myths he represents, how do we relate? As a secular atheist, cosmologies and mythologies of every sort have never interested me. What, then, can we speak of? Politics and aesthetics don’t necessarily coincide, nor do “we” all see or speak of the same experiences.’

Work by Aycoobo (Wilson Rodríguez). Photo: Matteo de Mayda / Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

In a sense, the Biennale very directly confronts each viewer with themselves – with your experiences, with your subsequent perceptions, and whether you are either more open or more closed to it all. In other words, it is our individual view of the world; or even more simply, our humanity. And at its deepest core, that’s what art is all about. As the British neuroscientist Daniel Glaser once said to me in an interview: ‘I don’t think we can get either from active scientific observation or from theory the fundamental answer to the question – What is it that you see? Because what you see is to understand that you need to understand who you are. What you see is the result of who you are, what your experiences are, what is your cultural immersion.’ That is, people with different cultural traditions and histories, as well as differing personal experiences, will look at the same work of art in completely different ways – how you see art is very directly influenced by who you are both culturally and personally.

Alleging that in his attempts at illustrating the topical and politically correct theme of both past and present colonialism, Pedrosa has just committed yet another form of colonialism by displaying indigenous art in a setting generally accepted as ‘the Olympics of Western art’, is a somewhat simplistic, albeit very convenient, commentary. Looking at it from a colonial aspect, i.e. with ‘western’ eyes, indigenous artists who exhibit at the Biennale will always be considered minorities and outsiders. However, their own cosmological point of view has, through time immemorial, allowed them to be connected to something larger than our modern-day generally accepted geopolitical boundaries. The strength of their culture, self-awareness and survival lies in living in union with the natural elements that surround their living space – water, land, mountains, jungle, animals and plants. They understand the importance of this union and its continuous interaction. Unlike many Westerners, indigenous peoples have never completely lost this connection, even when attempts have been made to deliberately eradicate it. They are able to speak freely, without division and without demarcation, about the relationship between human and non-human beings. Whereas we Westerners, more often than not, go into our forests excessively equipped with gear and gadgets, ready to confront any danger, real or imagined...if we dare to enter them at all. Not to mention that our own ‘inner forests’ can be just as threatening as a biological forest, seeing that both are inhabited by real and imaginary bogeymen alike. I remember many years ago in the Amazon, when I tried to start a conversation with a jungle guide about stress, and he – who had learned to speak 12 languages with the help of audio cassettes – didn’t really understand what ‘stress’ was.

Photo: Una Meistere

Consequently, Pedrosa’s Biennale is a bit like a fisherman’s net full of exotic fish that has just been emptied out onto the beach. The fish are many and colourful, but since there are none of the fish we are used to, either by name or type – such as herring, cod or halibut (not even a single tuna) – no one really knows what to do with them. There is no context provided by a museum, gallery, collection or auction house; in short, there is no framing. Most of the works are accompanied by the following note: ‘This is the first time [name of work or artist] is presented at Biennale Arte.’

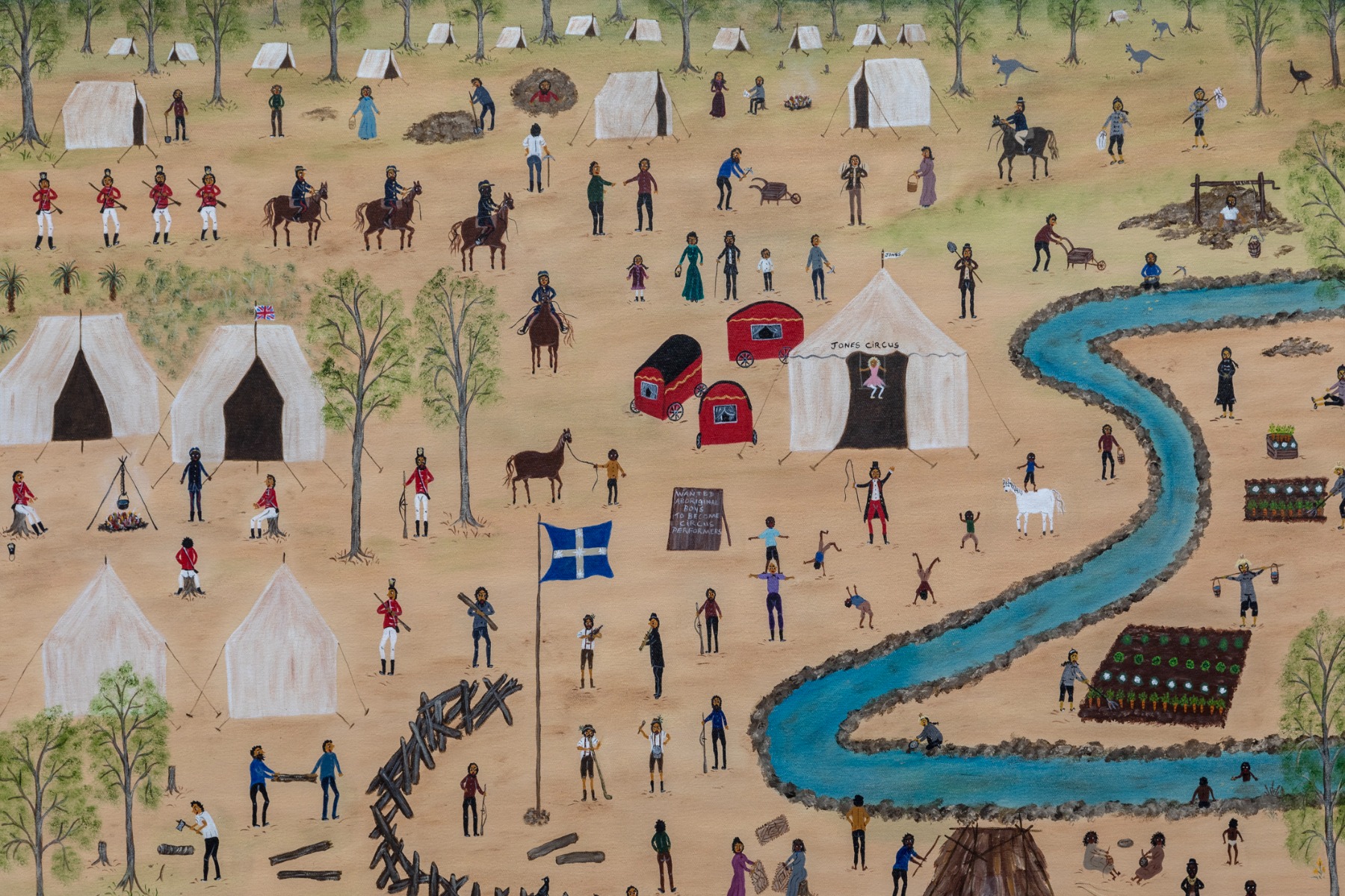

Marlene Gilson, Building the Stockade at Eureka, 2021. Acrylic on linen, 100 x 120 cm. Collection Martin Browne. Photo: Marco Zorzanello / Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

It is also true that the period of planetary evolution we are currently experiencing is unpredictable and far from certain. Perhaps that is why this exhibition, and the Biennale as a whole, is worth looking at from a completely different angle this time – not as an art event in the usual sense (and analysing it as such) but as a tool for exploring the world...an exercise for the mind and one’s emotional intelligence, both from a visual and an intellectual point of view. Looking inwards, feel how what you see resonates, and try to remain as free as possible from any prejudices, arrogance, or attempts to make it all fit into a frame.

In my experience of travelling, including in the regions that this Biennale has focused upon, being in another culture is a very good exercise for one’s open-mindedness since many of the preconceptions that you might have had upon arrival tend to disappear quite quickly. Because what are we doing here on earth, living through this life lesson, if not trying to figure out (while inhabiting a particular body) where we have ended up and who we are. And the current backdrop of global turbulence of all kinds only accentuates this state we are in, for it is no longer only the alien Others that are being threatened – by diseases of incomprehensible origin, colonialism, violence, etc. – but we are being threatened as well. In a way, the Biennale is an exercise in empathy – to learn and understand how differently what is happening on this planet can be perceived depending on who you are…including how to live and survive on it.

In a way, it also allows us to experience a completely different understanding of time as a concept, or time as a construct. In the language of the Native American Hopi tribe, for example, there is no word for ‘time’. For them, time is a continuum without a clearly defined past, present or future. In Hindu philosophy, time is an illusion – maya. The Australian Aborigines, on the other hand, have what they call ‘dream time’, a whole web of songs that connects the people to their land, their ancestors, and animals and plants. Their art is, in a sense, a navigational tool, a mapping of these territories in a visual language. It is also interesting to note that the Aboriginal gods mostly live within the earth. Nevertheless, they have a very special relationship with the stars and the way they read the sky.

Naminapu Maymuru-White. Mayaŋura malaŋu miḻŋ’miḻŋ. (Stars reflected in the River), 2023 Multi-panel bark painting, appr. 300×1100 cm. Photo: Marco Zorzanello / Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

This is perfectly reflected in the works on tree bark done with oil paint and embroidery by Aboriginal artist Naminapu Maymuru-White. Born at the Yirrkala mission station in Northeast Arnhem Land, Maymuru-White began learning to paint at the age of 12, picking up the skills from her father and his brother. Maymuru-White’s works are essentially a record of the Milŋiyawuy, the epic songline of her clan which connects the earthly dimension of life with the spiritual dimension. Maymuru-White is, it must be said, reasonably well known in the Australian art scene, having participated in group exhibitions both within Australia and abroad, and her works can be found in various private collections. The series of works on show at the Biennale is a tribute to the Milky Way (Milŋiyawuy), from where, according to legend, her ancestors originated. The works are created using a fine brush made of human hair, a wooden skewer, and a palette of natural earth pigments in white. Needless to say, their creation is an extremely time-consuming process.

In the book Yorro Yorro, an elder of the Ngarinyin clan describes the Aboriginal worldview: ‘Everything under Creation is represented in the soil and the stars. Everything has two witnesses, one on earth and one in the sky.’ Maymuru-White’s Yirrkala clan is where the largest collection of Aboriginal astronomical ideas and concepts – in the form of drawings – have been found. Aboriginal people associate the Milky Way with a river in the sky in which the spirits of their ancient ancestors live, surrounded by fish and water lilies (stars), thus emphasising the interconnectedness of everything – heaven and earth, life and death. Maymuru-White’s work reveals that the web of dream lines on earth are the same as those in the sky, the serpent-like river casting almost identical twists and turns in the starry universe as on earth. Interestingly, legends of the ancient Baltic peoples also indicate that we may have descended from the Milky Way. Moreover, modern science has confirmed that the same elements that make up our bodies were synthesised in the stars over billions of years ago. In fact, it is likely that some of the hydrogen (by mass, about 9.5% of a human body) and the trace amounts of lithium in our bodies were produced by the Big Bang.

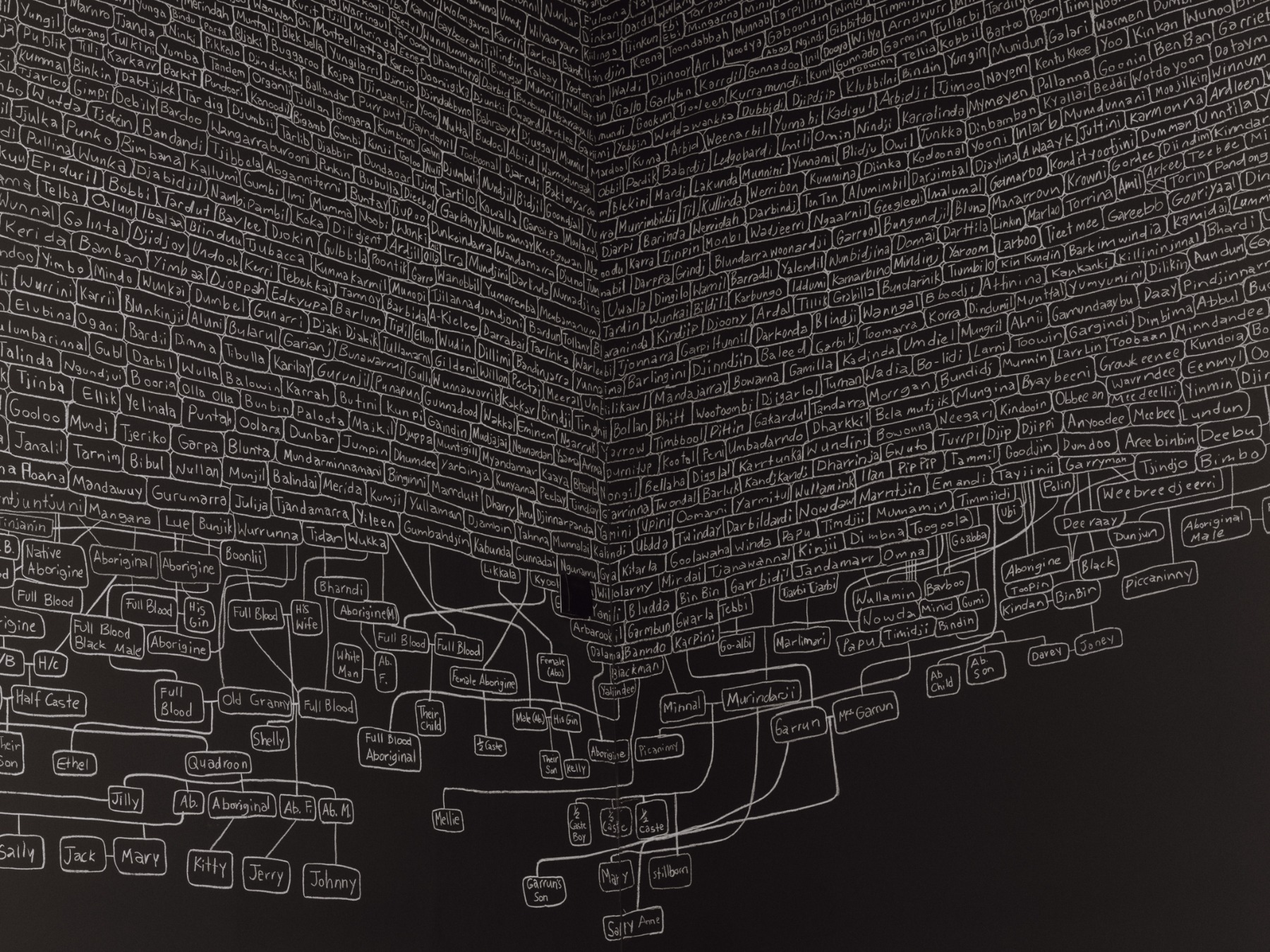

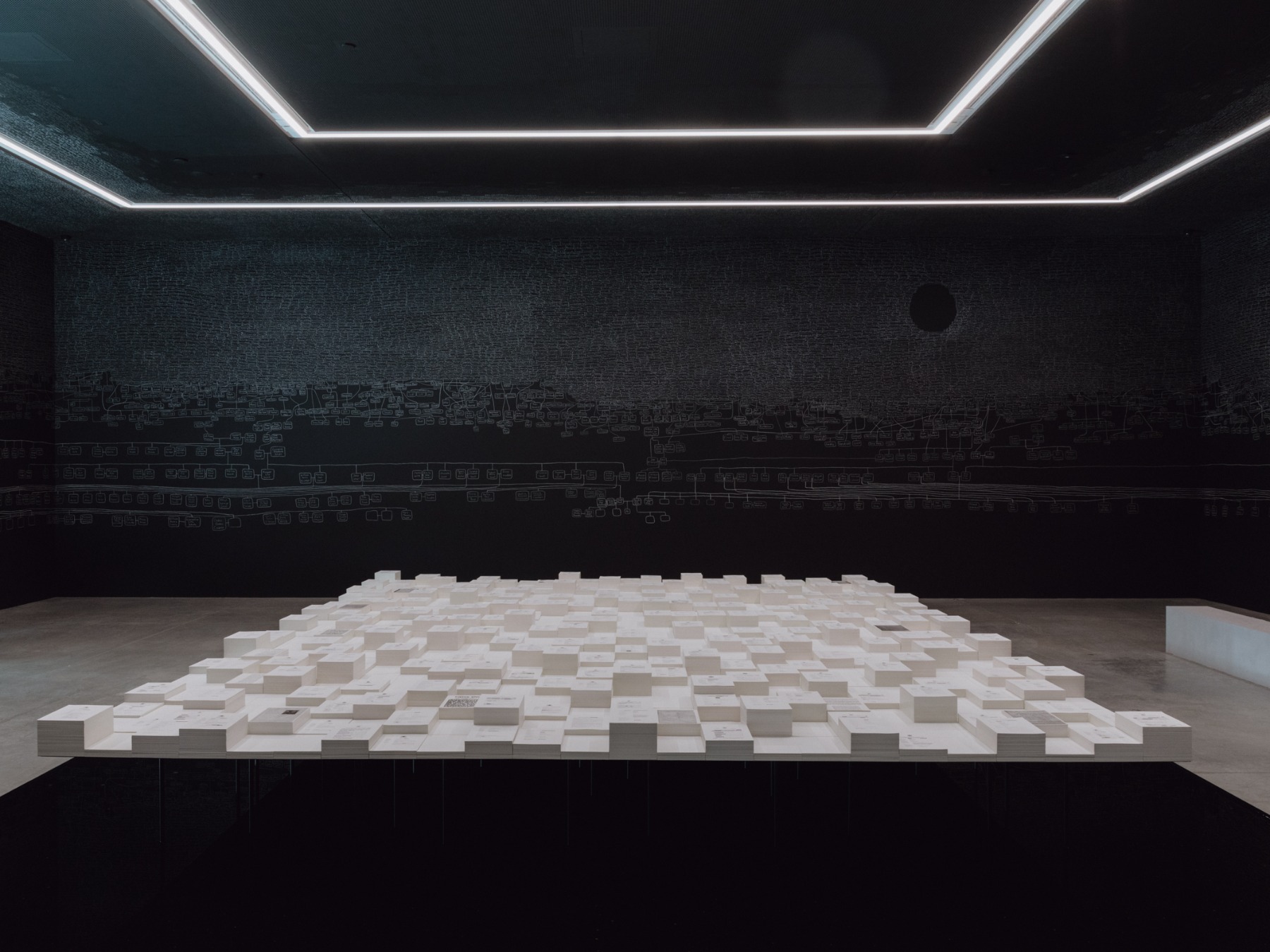

Australian pavilion. Photo: Matteo de Mayda / Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

The fact that the Australian pavilion was awarded the Golden Lion prize for Best National Participation at the Biennale will not, of course, solve political or economic issues, nor will it solve or alleviate the problem of the so-called ‘Stolen Generations’, which refers to the Aboriginal children forcibly removed from their families by Australian government agencies between the mid-19th century and the 1970s, thereby depriving the children of any contact with their culture, environment or parents. Such cases continue to flare up from time to time, more or less quietly, and the Aboriginal voice continues to carry little weight. The only thing the Biennale can do is make that voice a little louder.

Mataaho Collective. Takapau, 2022 Installation (polyester hi-vis tiedowns, stainless steel buckles and j-hooks) Site specific reconfiguration Museum of New Zealand, Te Papa Tongarewa. Photo: Marco Zorzanello / Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

The second Golden Lion of the Biennale, for Best Artist, went to the Mataaho Collective from New Zealand, which is made up of four Maori women artists. As a collective, they have been together for more than 10 years, creating contemporary installations rooted in tribal traditions that provide insights into Maori life and knowledge systems. The work on display at the Biennale, Takapau, was created in 2022 and is inspired by whariki takapau – specially woven rugs used for very special occasions, including the birth of a child. In Maori culture, the mother’s womb is a sacred place where the baby is connected to the divine, while the takapau marks a moment of transcendence between light and darkness – Te Ao Marama (the world of light) and Te Ao Atua (the world of the gods). The play of light is also one of the most magical elements of the work, bringing the viewer into an open-air world that is in constant flux; in fact, the work is made of very prosaic industrial materials – grey reflective trucking straps used to secure cargo with steel hooks and buckles. But perhaps the most unique feature of the Mataaho Collective is that the making of any work is a wānanga (forum) for them, as it embodies not only knowledge and its transmission but also collective work; they laughingly call themselves ‘four brains and eight hands’. The work of the Mataaho Collective highlights another very clear trend of this Biennale: the strong dominance of textiles, which is also very much in line with general trends in the art scene at the moment.

MAHKU (Movimento dos Artistas Huni Kuin). Kapewe Pukeni [Bridgealligator], 2024 Site-specific installationm 750 m2. Photo: Matteo de Mayda / Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

The hyperdimensional world

The entrance to the main pavilion in the Biennale’s Giardini has been painted by the Huni Kuin collective MAHKU from the Brazilian Amazon. On Opening Day, they are all there, happily chatting with anyone interested in starting up a conversation… even if only with a smile. The mural took 45 days to paint and depicts the Huni Kuin world origin myth. According to their legends, the world originated from an alligator. The disarming brightness and visual appeal of the work are only the outer shell of this work, however. Every element of this drawing is important, as the painting embodies the Huni Kuin’s story of the forces that shape their world, one where human and non-human aspects of the environment are equally present. The visible is intertwined with the invisible, the aesthetic, and the spiritual.

MAHKU (Movimento dos Artistas Huni Kuin). Kapewe Pukeni [Bridgealligator], 2024 Site-specific installationm 750 m2. Photo: Matteo de Mayda / Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

The human figures and natural elements in the painting are united by a single pattern, known in the Huni Kuin language as kene, or ‘true drawing’. They also call it the ‘snake drawing’ because according to their mythology, these patterns were taught to their ancestors by a boa constrictor. They are present in almost every visual element of Huni Kuin culture and are also used as drawings on the body. The drawings also represent the world into which they are brought and connected to by the sacred plants. One of these is nixi-pae, which Westerners call by the generalised name of ayahuasca, although each of the indigenous tribes has its own name for this combination of plants. For centuries, nixi-pae has been, and continues to be, a teacher of the Huni Kuin and other indigenous peoples. Besides ceremonial practice, is also used for sacred moments, which in the Huni Kuin tradition includes the creation of art. When asked if nixi-pae was also present in the creation of the Venice mural, the MAHKU team smiles knowingly. Questions about the obvious can sometimes be quite silly.

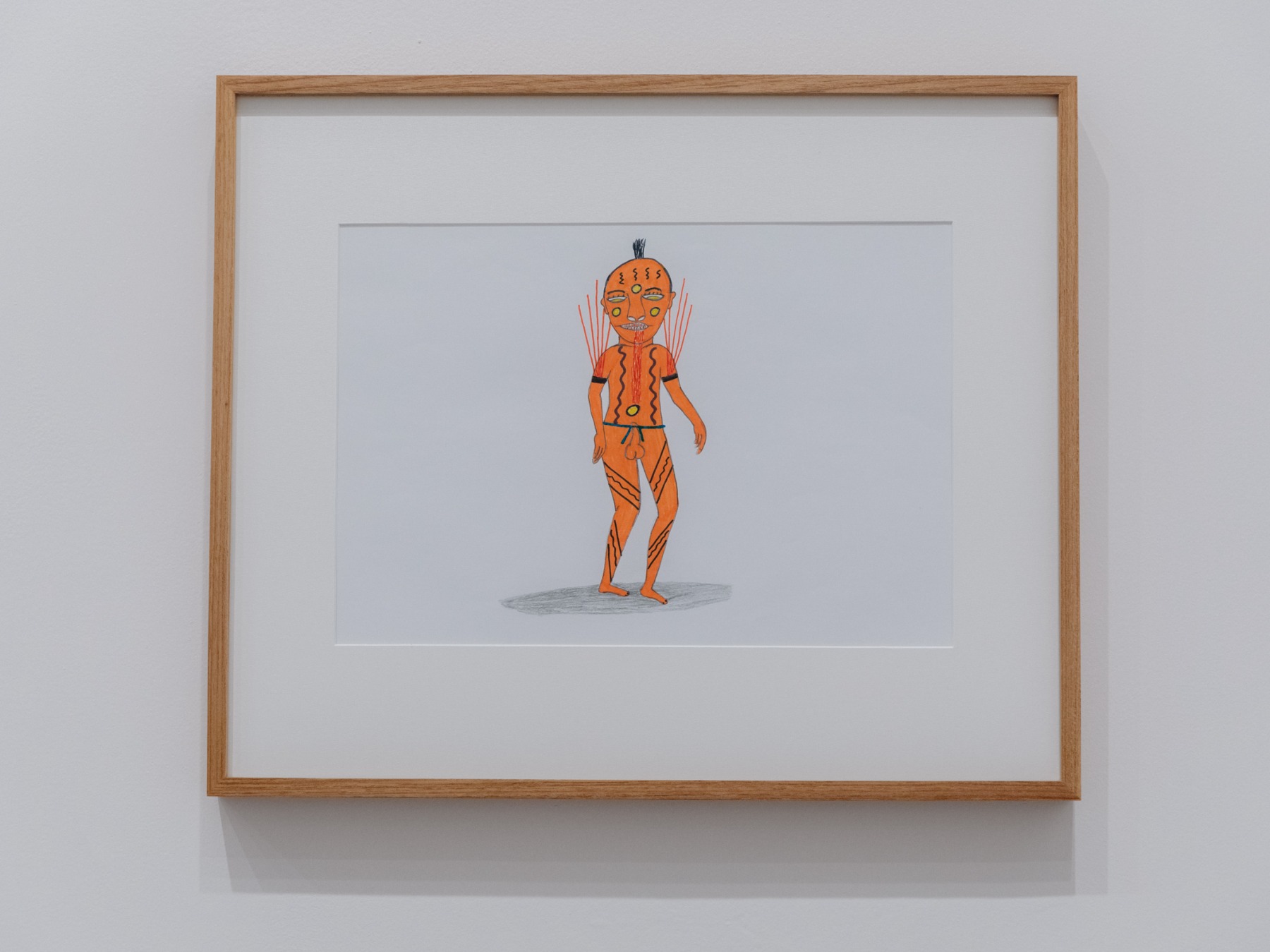

Joseca Mokahesi Yanomami.

Kami xapiri yamaki hwaithaki

yayoa nikere, inaha xapiriyamaki pihi kuënëhë maimi, ai yamaki hwaithaki rapenikere, ai

xapiri yamakihe marokoxi.

Kami xapiri yamakinë

në wari yama a xëi maprario

tëhë, yamaki tirei xoao tëhë,

inaha yamaki imiki kuo, kuë yaro yamaki areremorayu, 2011. Graphite, color pencils and felt-tip pen ink on paper

30 × 42 cm. Photo: Matteo de Mayda / Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

The mythology of his tribe is also depicted in the drawings of Joseca Mokahesi Yanomami, who lives in the Watoriki community in the Yanomami Indigenous Territory of the Brazilian Amazon. Joseca Mokahesi tells the story of his tribe’s daily life and the myths and spirits that are present in it. Each drawing is accompanied by a description that tells the story in a very simple way. For example, Yamanayoma, the feminine spirit of the bee, is depicted as a woman who treads tiny and determined steps on land and sees to it that food continues to grow well. As we know, thanks to monocultures and the use of pesticides, many bee populations around the world are in danger of dying out. Given their important role in the planet’s overall ecosystem, the threat to bees is also a threat to humanity as a whole, since the stability of the bee population is closely linked to the stability of the overall biodiversity, and therefore to the stability of the food that humans need. Yanomami illustrates this precarious situation in his own language.

Joseca Mokahesi Yanomami. Yamanayomani thë urihi karukai xoao tëhë wamotima thëpë raruu totihio tëhëma thëa. Yamanayoma a, 2013. Graphite, color pencils and felt-tip pen ink on paper

30 × 42 cm. Photo: Matteo de Mayda / Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

Colombian-born anthropologist Luis Eduardo Luna, who has extensively studied visionary art and had a long collaboration with Amazonian mestizo artist Pablo Amaringo, once told me in an interview: ‘Originally, probably not every Amazonian culture used psychoactive or sacred plants, and not every art is based on them. We don’t really know; we’d have to go back in time to find out. But certainly, as far as we know, a lot of the art is based on people’s contact with such plants. But again, I cannot generalise.

‘(...) Pablo (Amaringo), as well as Peruvian artist Agustin Rivas, who was an artist before he become shaman, they both told me exactly the same things. They said that it was ayahuasca that taught them how to mix colours or make sculptures. Agustin told me that he would take pieces of wood, put them on his shoulder, and the piece of wood would make a different sound every time. And that sound somehow gave him the shape of what he was going to do with that piece of wood. So, there’s another synesthetic process.

Santiago Yahuarcani. El Mundo del Agua, 2024

Natural pigments and acrylic on llanchama, 283 × 671 cm.

Photo: Andrea Avezzù / Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

So, what are they looking at? Well, I think what happens is that the picture of reality is much broader and more varied than we think it is. Simply because they have a conception of the world that is full of spirits, everything is full of spirit. It’s hyper-dimensional in a way, there are many dimensions. And with ayahuasca you can go into these other dimensions. You know, the world is not only that which we see with our eyes; it’s much richer. And of course, if you have more input, then there are more things coming to you.’

Those who have used ayahuasca in a ceremonial setting know that it has a healing knack for shaking out seemingly fixed concepts constructed by the mind...sometimes quite brutally and unpleasantly. Moreover, this sacred herbal compound, or the spirit that dwells within it, cannot be resisted, nor can your personal truth be imposed upon it – it will simply break it down into tiny shards, and without the slightest sense of piety. Whatever it may be like, the ayahuasca experience is real and authentic. It is a feeling that is clearly embodied in the art of indigenous peoples. And at the same time, it is a feeling that we in the West have lost to some extent, blocking some of our senses and sensory acuity with comfort and technology. Now we are trying to recover it through various practices that indigenous peoples in different parts of the world have known for a long time, from breathing to ritual dance and meditation. Moreover, we are legitimising sacred plants with the tools of modern science.

Incidentally, this is not the first time that the Huni Kuin people have been represented at the Venice Biennale. In fact, their first visit in 2017, as part of Brazilian artist Ernesto Neto’s Um Sagrado Lugar project, provoked an avalanche of criticism. ‘Now in the art scene there are people talking about the forest, about the indigenous and especially the Amazon indigenous force and knowledge, about everything... But when I went to Venice and said that Western society needs indigenous knowledge for the balance of the planet, the critics turned their backs and said, “Ernesto is using the indigenous.” They did not want to talk about it. Capitalism and the Western knowledge model have a key, and we’re allowed to criticise the system; that’s a part of democracy. But you can’t criticise the knowledge model; that’s a heresy. The Huni Kuin who were there, they’re spiritual and political leaders; they represent the knowledge they have. It was not just a project I did with some indigenous group – this was life and death, life alive, life for life! People only want to see interest and profits, because it’s easier, it’s a smoke screen.

(...) But this is the world we are in. And in these situations, especially places like the Venice Biennale, where there’s one work after another, you have all these pots putting out energy from everywhere. We need to begin to have a new way of reading what we’re doing as artists on this planet, as curators on this planet, as big institutions on this planet. We must have more respect, real respect towards the artwork. And not this respect of the celebrity or of the power of the market.’ said Neto at the time.

During the opening days of this year’s Venice Biennale, Ernesto Neto was in Portugal, where his installation Our Boat Drum Earth opened just a few days ago at MAAT, Lisbon’s Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology. “The work embodies ‘that ‘Gaia world’: ancestral, pre-colonial, and even pre-human – a planet obviously shaped by violent events and occurrences, such as the enforced displacement of millions of enslaved people during the colonial processes that marked history and the relationship between Portugal and Brazil, among many other countries. But it’s also a planet where, from the mix of races, populations, and peoples, surprising cultures and worldviews emerge, whose strength and beauty one must recognize, reaffirm, and celebrate,” says curator Jacopo Crivelli Visconti in designboom. The exhibition is accompanied by a musical programme featuring musicians from all over the world, but especially from the African and Asian diasporas. This included drumming. As is well known, missionaries once forbade African slaves in Brazil to play drums because they feared the power of this instrument, which has a consciousness-expanding effect, and believed that the rhythm of the drums summoned the devil.

On the opening day of the Biennale, Senegalese drum rhythms also filled the Arsenale’s main exhibition, Antonio Jose Guzman and Iva Jankovic’s project Orbital Mechanics, which embodies the story of the colonial history of indigo textiles.

A reminder of our common humanity

Brazil also devoted its national pavilion at the Biennale to indigenous peoples by featuring artists from the Tupinambá tribe, which lives on the country’s oceanic coast. The pavilion’s title, Ka’a Pûera: we are walking birds, embodies the tribe’s tragic history: like many other indigenous tribes in Brazil, they had been displaced from their historic lands for a long time, and up until 2001, were even declared to have died out. One of the elements of the exhibition is the maraca, a rattle-like musical instrument used by the Tupinambá and other indigenous Brazilian tribes in healing rituals.

Photo: Una Meistere

But perhaps one of the most remarkable aspects of the Biennial is that for the first time in its history, the United States is being represented with a solo exhibition by an indigenous and queer artist – Jeffrey Gibson. The title of the exhibition, the space in which to place me, is universal – as much a reference to the struggle of indigenous peoples and Others for their rights, as to the desire of any individual in an increasingly complex world. By using colour and skilfully stimulating joy as an emotion in his visitors, Jeffrey Gibson conjures up an alternative and slightly psychedelic world where seriousness and the capacity to enjoy life coexist, and in circumstances that are very complicated.

Jeffrey Gibson: the space in which to place me. Photo: Una Meistere

When I asked during a brief conversation with Kathleen Ash-Milby, one of the curators of the pavilion and curator of Indigenous Art at the Portland Art Museum, what are the main lessons she has learned from this project, she replied: ‘Well, I think having Jeffrey Gibson here representing the United States is a really significant moment. It’s not only big for him personally, but it’s also the first time an indigenous artist from the United States has been chosen to represent the country in a solo exhibition at the Venice Biennale. So, yes, it’s a huge deal. I believe that the messages Jeffrey is conveying through his work aim to include people and foster a sense of welcome. Moreover, it’s a celebration of Native American culture and art, not just about him as an individual, but about the wider community.

Jeffrey Gibson: the space in which to place me. Photo: Una Meistere

I think this is a really important time for art because it reminds us of who we are as human beings, what we have in common, and what we share. Sometimes, artwork can convey far more than words. It’s crucial to be reminded of our shared humanity.’

Kathleen Ash-Milby is also convinced that the division between contemporary and traditional art in today’s art world is ‘somewhat arbitrary and artificial. Native artists should have the freedom to express themselves as they wish. Many, like Jeffrey, draw from multiple traditions, including contemporary art, and are truly embracing the essence of being an artist. It’s time to stop confining artists to boxes because Jeffrey, for instance, defies categorization. That’s what makes his work truly remarkable.’

Jeffrey Gibson: the space in which to place me. Photo: Una Meistere

Jeffrey Gibson himself says that the aim of the exhibition is to ‘place Indigenous histories and narratives, aesthetic histories, and material histories into a global context, which they have been a part of for a very long time. Historically, when we look at museum collections, oftentimes we don’t know the names of the makers, we don’t know how things were acquired. We’re doing what we can, or I’m doing what I can, to give them the same integrity as makers, to acknowledge that they had choices, that they were choosing to use materials in times of trauma and duress, and continued making beautiful objects. The way that I’ve come to understand those objects at this point is really about making a microcosm of possible hope, a microcosm of possible freedom.

I’m 52 years old. I started going to clubs early, at the age of 13; they made me feel normal. I began attending gay clubs in the 80s and the 90s. I belonged to a generation that didn’t understand that the generations above me had just lost all of their communities to AIDS. As I got older and began to listen to that music a little bit more, I realized they were cries for help, demands for justice, equity, and acknowledgment. That was the kind of thing that really taught me to start looking at how things, which we might simply call pop music, decorative art, wallpaper, lace, or fashion, have always been very powerful elements surrounding us.

For me, I wanted to not only address Native American history but also black American history in the United States. My family has roots in Mississippi and Oklahoma. I’m sure that I have African blood flowing through me. And I think it’s amazing that race and heritage continue to be such pivotal parts of conversations that we have, yet we haven’t found a comfortability to talk about them.

There are so many gaps in history. Although I’m focusing on my personal narrative here as a queer, indigenous man, among many other things, I know that everyone here is an intersection of so many disparate histories, and we haven’t written history in the way that it should be written, right? I mean, if we knew the whole story, it’s actually very logical why we are where we are today, and we’ll be happy.

So I think filling in those gaps, but also collecting as many first-person narratives and making sure that you pass that on, shows how complicated we are. And with that complication, I think we’re also extraordinarily capable of handling the challenges that we exist with now, but they’re certainly coming our way.

You know, I always tell people, it’s like, you just can’t guarantee anything, you know? You do your best, but I really believe that things unfold, and my job is to put things out in the world that I believe in. However, I can’t control what happens, you know? So, I felt the timing was right. I did feel like I have figured myself out in a way that I know what I want to say and how I say it as an artist. That’s what made me feel comfortable to do it now. But, I truly hope there are many more after this.’

Jeffrey Gibson: the space in which to place me. Photo: Matteo de Mayda / Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

And perhaps this is the greatest humanistic contribution of this Biennale – it tries to draw the viewer’s attention to certain points on this globe and to certain beliefs, cosmologies and myths, thus challenging the viewer to learn a little bit more about something. Of course, only if the viewer is willing, because this something is nothing other than themself...and someone who, at some point, may also turn out to be a complete stranger.

Titulbilde: Joseca Mokahesi Yanomami. Xapiri Parahorioma yani wahariomapë, roko ahikini pata hore ria reëri ehuhua kurarkiri, roko ahiki pata hore wakara praayaria kurakiri. Awei kami xapiri yamaki urihipë hoximaimi, yamakirihipëhore horepë siprërëhe xatiti totihi. Kuë yaro kami xapiriurihi a xamio pëha yamaki ithoimi, 2013

Graphite, color pencils and felt-tip pen ink on paper, 30 × 42 cm

Photo: Matteo de Mayda / Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia