Robert Ryman Meets Posthumanism

Ēriks Apaļais

Robert Ryman Meets Posthumanism

Elza Sīle, an artist trained at the Art Academy of Latvia and later at Zurich University of the Arts (ZHdK), draws heavily on the influences of artists like Robert Ryman, Cy Twombly, and Louise Bourgeois. Her engagement with Minimalism, Abstract Expressionism, and Post-Minimalism informs her own artistic language, which she has developed within the framework of expanded painting. Sīle frequently incorporates industrial materials — such as aluminum and plaster—alongside traditional art media like textiles and oil paint, crafting works that challenge established norms. Often playing the role of provocateur, her art provocatively redefines fragile materials, delivering the subversion through a playful yet intimate handling of form, as if “whispering” its defiance.

Photo: Pēteris Rūcis

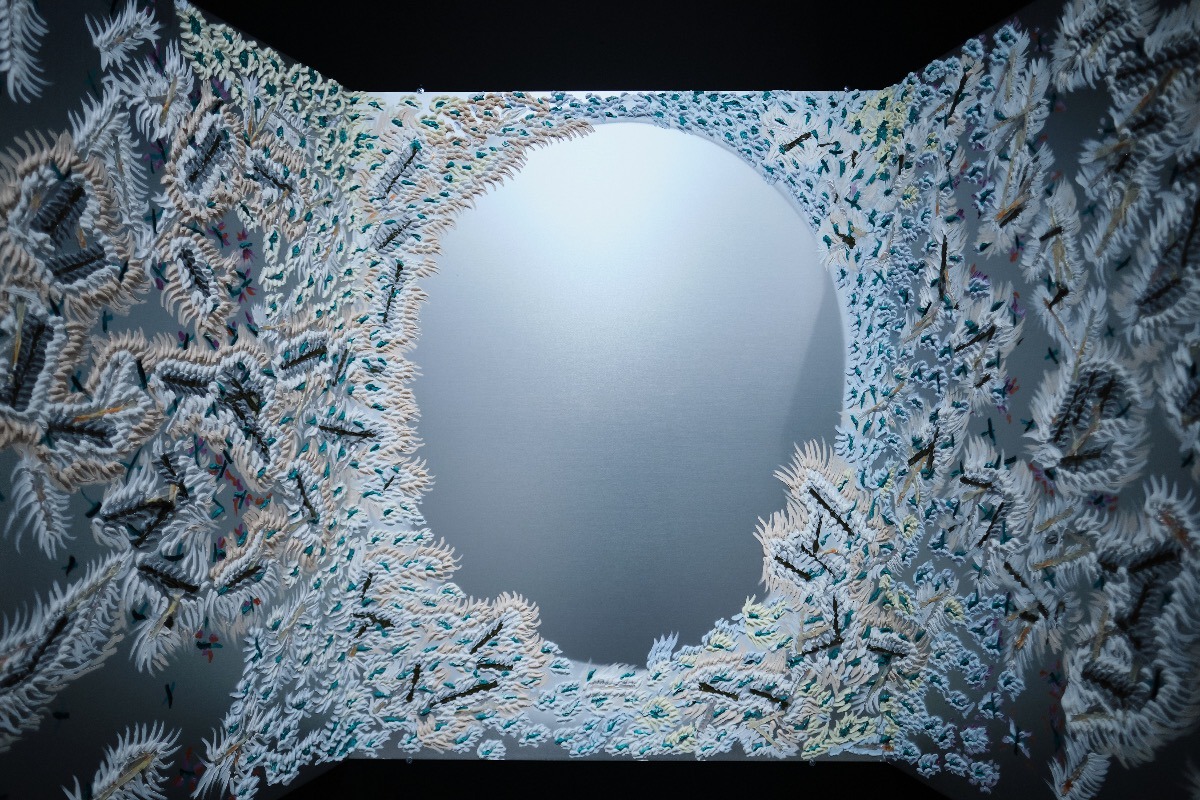

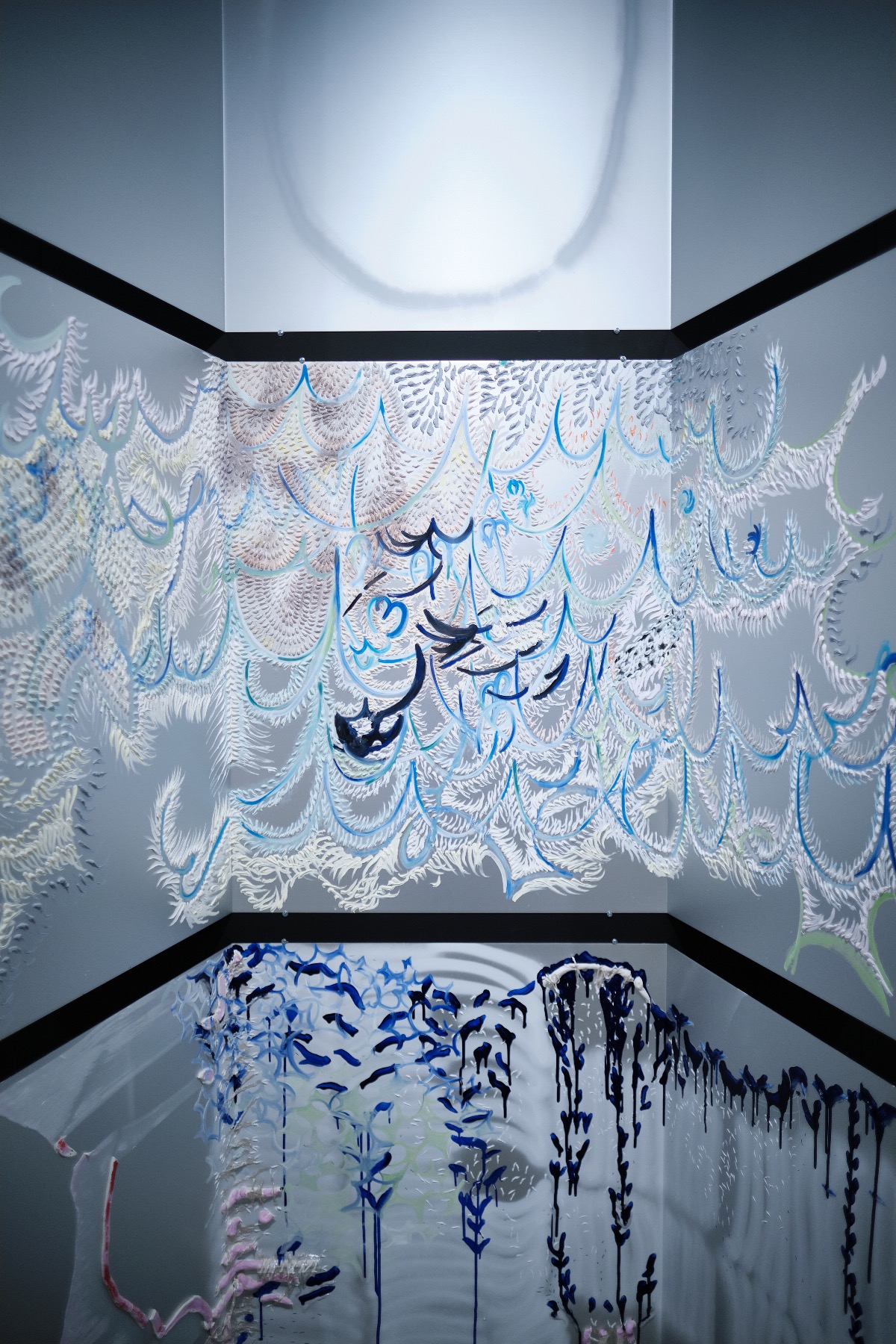

In her latest exhibition, Zaķīšu pirtiņa/Bailes un Trīsas (“Bunny Bathhouse/Fear and Trembling”), Sīle transforms the space into a complex installation where images, suspended sculptures, and floor-bound objects co-exist, breaking from conventional modes of display. The sculptures defy the traditional use of pedestals, and images are hung in experimental ways, enhancing the immersive effect of the exhibition.The absence of pedestals and the experimental ways in which works are presented create an engaging space, but the visual density sometimes overwhelms the viewer, muddying the conceptual clarity. From a distance, the space takes on the appearance of an enlarged architectural model—a nod, perhaps, to the artist’s upbringing in a family of architects, where such models may have influenced her approach to space and scale. In this way, Sīle’s installations seem to echo a childlike sense of wonder, filtered through an adult’s analytical lens. The result is an exhibition characterized by an oxymoronic blend of structure and magic.

Sīle’s use of preparatory sketches, diagrams, and notes as final artworks themselves raises interesting questions about process versus product. However, at times, her pieces border on mere visual illustrations of ideas rather than fully formed autonomous works. The artist’s interrogation of material and form—between plane and brushstroke, image and sculpture—sometimes feels like a checklist of academic questions, lacking the urgency that such inquiries could carry. For instance, as the texture of paint thickens, it transforms into a more sculptural object. This conceptual play extends into questions about posthumanism, where materiality is central: How does a brushstroke change when applied in ceramic on aluminum? How does a painterly gesture become a written sign? These inquiries are at once technical and analytical, opening the door for interpretations that bridge medium-specific critique and broader posthumanist ideas.

Despite her embrace of contemporary materials and modes, Sīle’s works remain tethered to a critique of Minimalism, Abstract Expressionism, and Post-Minimalism. Her exploration of these legacies often offer fresh insights into the roles of gesture, materiality, and form. However, at times, her approach feels overly direct, as with her translation of painterly marks into plaster reliefs, which can seem literal in their critique of medium. The dematerialization discourse she engages in also risks redundancy, where the concepts seem almost overly familiar within contemporary art’s critical lexicon.

A key conceptual thread throughout the exhibition is its engagement with posthumanism, though here, it is combined with a deconstructive approach. Rather than treating the material as autonomous, Sīle continues to subject it to critical interrogation within the frameworks of art history. It’s as if she revisits Ryman’s restrained brushwork or Twombly’s spontaneous scribbles, but through a posthumanist, even mystical, lens. While this can yield intriguing results, the works sometimes feel bogged down by the weight of their conceptual underpinnings. The dense visual syntax can cause the artworks’ arguments to lose clarity, making it difficult to resolve the tension between critical rereading and decentralized views on materiality. This tension is central to the exhibition’s aesthetic, creating a conceptual friction that both energizes and complicates the work. There is a lingering sense that Sīle is grappling with too many concepts at once, and this results in a body of work that feels overcrowded, both visually and intellectually.

In the exhibition’s curatorial text, a post-apocalyptic scenario is invoked, with art envisioned as a playground for speculating on humanity’s creative expressions after the collapse of civilization. Sīle imagines a return to art’s primal functions—ritual and symbol-making—unburdened by market forces. The materials surviving this imagined apocalypse, such as plastic and aluminum, are seen not as pollutants but as the inevitable detritus of human existence, now repurposed alongside organic materials to forge new, hybrid futures.

In conclusion, while Sīle’s worksometimes feels weighed down by the complexity of its conceptual ambitions, it also exhibits genuine curiosity and a thoughtful engagement with art historical discourse. Her merging of autobiographical elements with broader themes like posthumanism invites interesting dialogue, but the layering of ideas can make the exhibition feel overcrowded, both visually and intellectually.

***

Exhibition “Bunny Bathhouse/Fear and Trembling” by Elza Sīle was on display in the Great Hall of the exhibition hall “Riga Contemporary Art Space” from September 7 to October 27, 2024.