I have no sentiment for watching the world come to an end

A conversation with Elza Sīle / shortlisted for the Purvītis Prize 2025

‘Imagine a world after a global catastrophe in which you are one of the few survivors. (...) You decide to nevertheless have some hope, and want to express this newfound hope in some physical form – but what might that look like?’ These are lines from the conceptual layout of the exhibition Zaķīšu pirtiņa / Bailes un trīsas (Bunny Bathhouse / Fear and Trembling) by Zurich-based Latvian artist Elza Sīle. The exhibition was on show at the Riga Contemporary Art Space in autumn 2024.

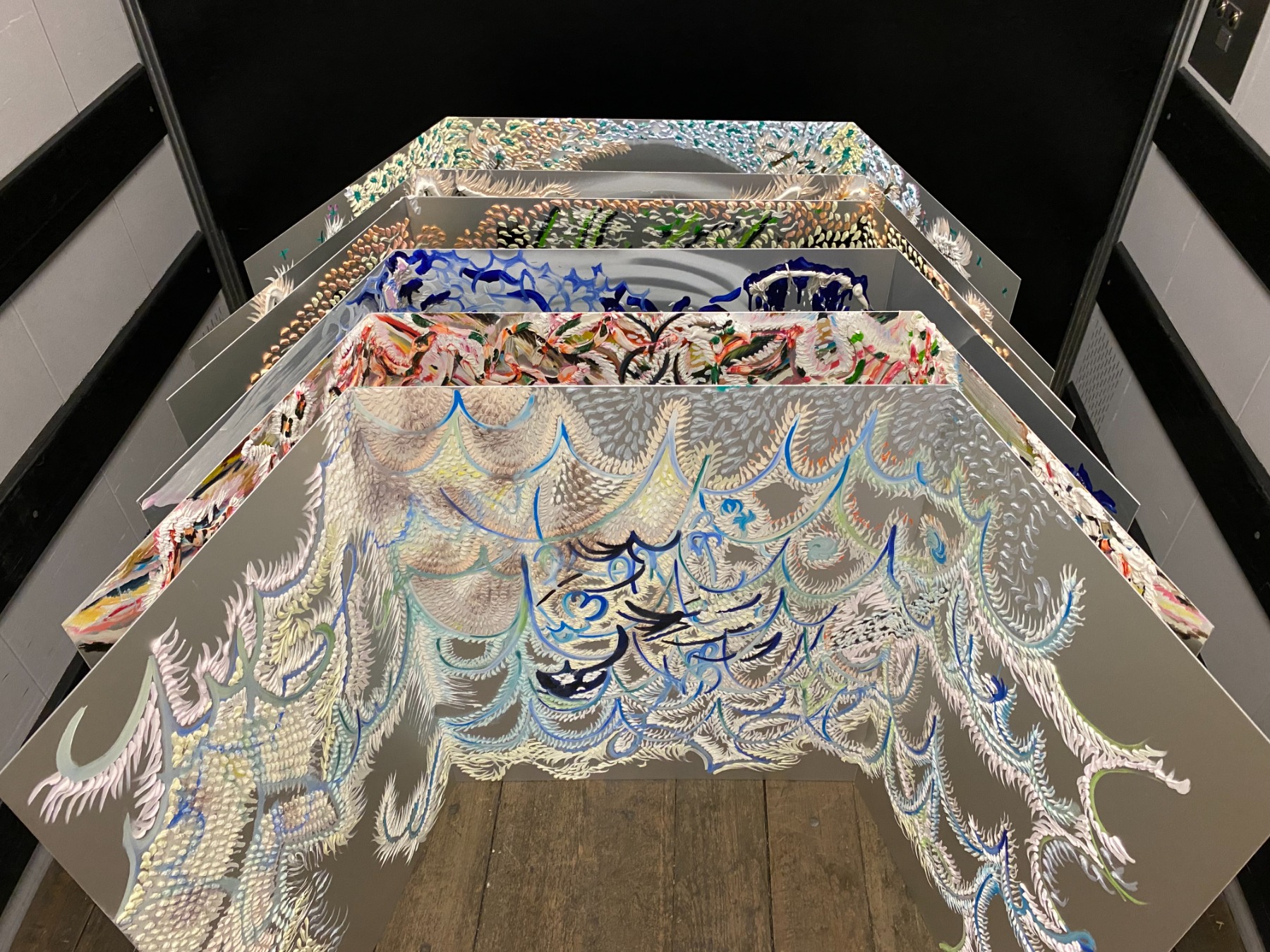

The exhibition’s narrative is concentrated and highly focused, but unfolds in an impressive and dense maze of 200 paintings and objects. The use of the endearing classic Latvian poem Bunny Bathhouse, familiar to every Latvian child, may at first seem both dissonantly incomprehensible and intellectually challenging, but as Elza wrote to me (our ‘conversation’ took place in writing): ‘Lately, I have noticed that some words – such as “death”, “mental illness”, “thorns, chains and hooks”, “depression”, “neuroses”, “catastrophe” and “apocalypse”, as well as “intellectualism” – are easily accepted, whereas words like “bunny baths”, “strawberries” and “brightness” seem to make people cringe.’

The exhibition Bunny Bathhouse / Fear and Trembling is a tribute to the apocalypse, which, among other things, has always captured the attention of art. Why is that, do you think? What is it that attracts you to this narrative? Do you feel it in the current zeitgeist, or are you coming at it from a completely different angle? This exhibition is not your first to have reflected on apocalyptic themes.

I’m not so sure that art will continue to exist in its contemporary forms of commercial and institutional practice for much longer. I’m not sure how soon, but it’s very likely that most people will find themselves in a state of constant migration – with portable possessions, tents, and the ability to adapt and improvise in random situations. Of course, the billions of euros worth of art and valuables stored in the Geneva Freeport can be transported to the St. Gotthard high-security vaulting facility, where it will be under the supervision of the neutrally silent dwarves who live in these Swiss mountain boreholes.

My trips to Bangkok, Mexico and Puerto Rico, and my observations while in Miami, New York and Zurich – in terms of human actions and states of mind – could all be summed up into a split-second scene of a film playing in your head, in which an unseen narrator asks the audience: ‘Well, if you had to answer honestly... is what you see worth existing?’ In proportion to the consumption of resources and the pollution most of it produces, unfortunately, I’ve often had to answer, ‘No.’ I feel sorrow for the opportunities that people have/have been given, but which they have squandered. However, along the way I have also met people who, if there were many more just like them, the world would be a better place.

The concept of the ‘bunny bathhouse’[1] is distinctly Latvian and a part of our literary canon.What does it mean to you, and what role does it play in your exhibition – in the context of this intellectual game?

I chose to enter the art game not to be a piece moving about the board, but because I was attracted to the game board itself. I used to snowboard, and at age 17 I accepted that if I want to take part in artistic disciplines, I really shouldn’t risk breaking an arm, but I can still enjoy an intellectual ‘freeride’. In snowboard terminology, this means snowboarding on terrain with fresh snow that is often unaltered or unpatrolled, and so your values and positions are recorded through your movement style. If I had lived in an earlier time, I would have chosen the natural sciences, archaeology or alchemy; in a futuristic scenario of unlimited resources, I would have looked for ways to manage the growing desert wastelands, or for new defences for cities to prepare themselves against an encroaching ocean. In short, the ‘playing out of freedom’ is part of my motivation. Lately, I have noticed that some words – such as ‘death’, ‘mental illness’, ‘thorns, chains and hooks’, ‘depression’, ‘neuroses’, ‘catastrophe’ and ‘apocalypse’, as well as ‘intellectualism’ – are easily accepted, whereas words like ‘bunny baths’, ‘strawberries’ and ‘brightness’ seem to make people cringe. As if ‘depth’ always implies something dark, and ‘meaning’ is always a reflection on the negative. I think that after a few hundred years of use, they have become clichés. That’s why it’s so easy for an artist to look like a ‘real and deep artist’ when they reflecting on something ‘damning’. So, without wearing any protective clothing, I decided to try out the alternatives.

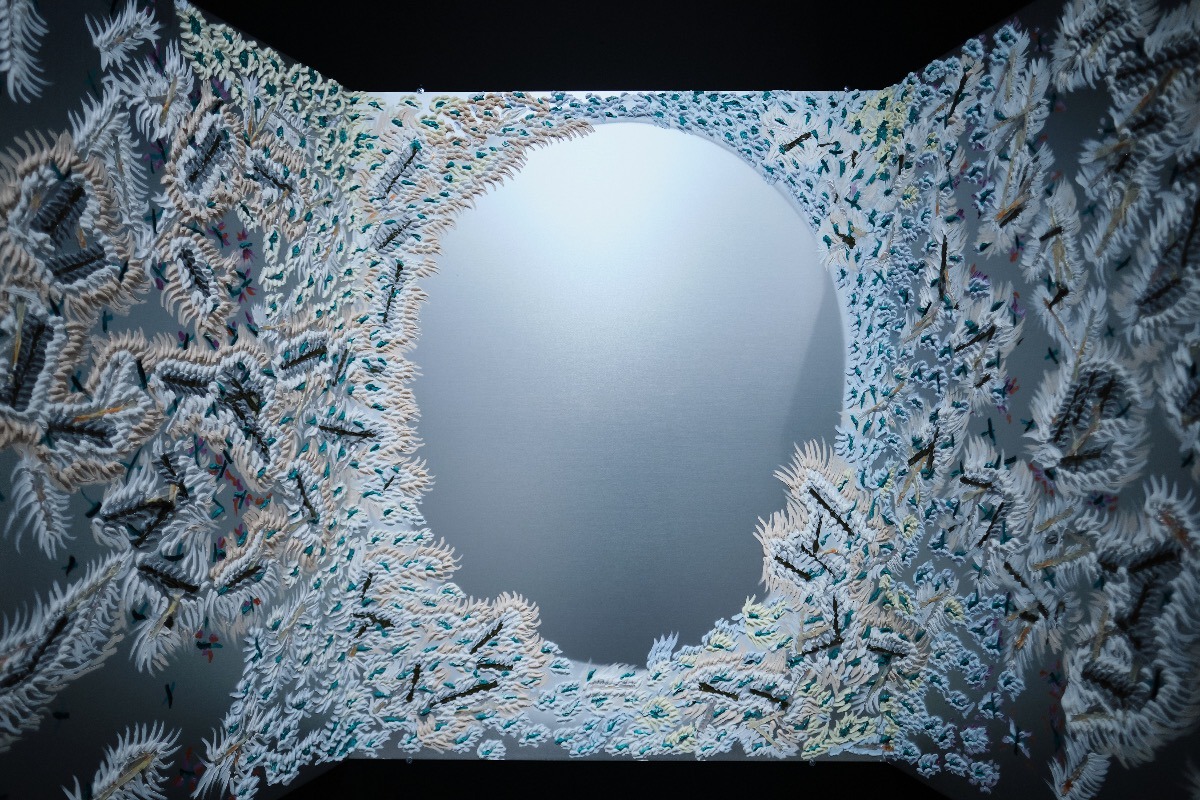

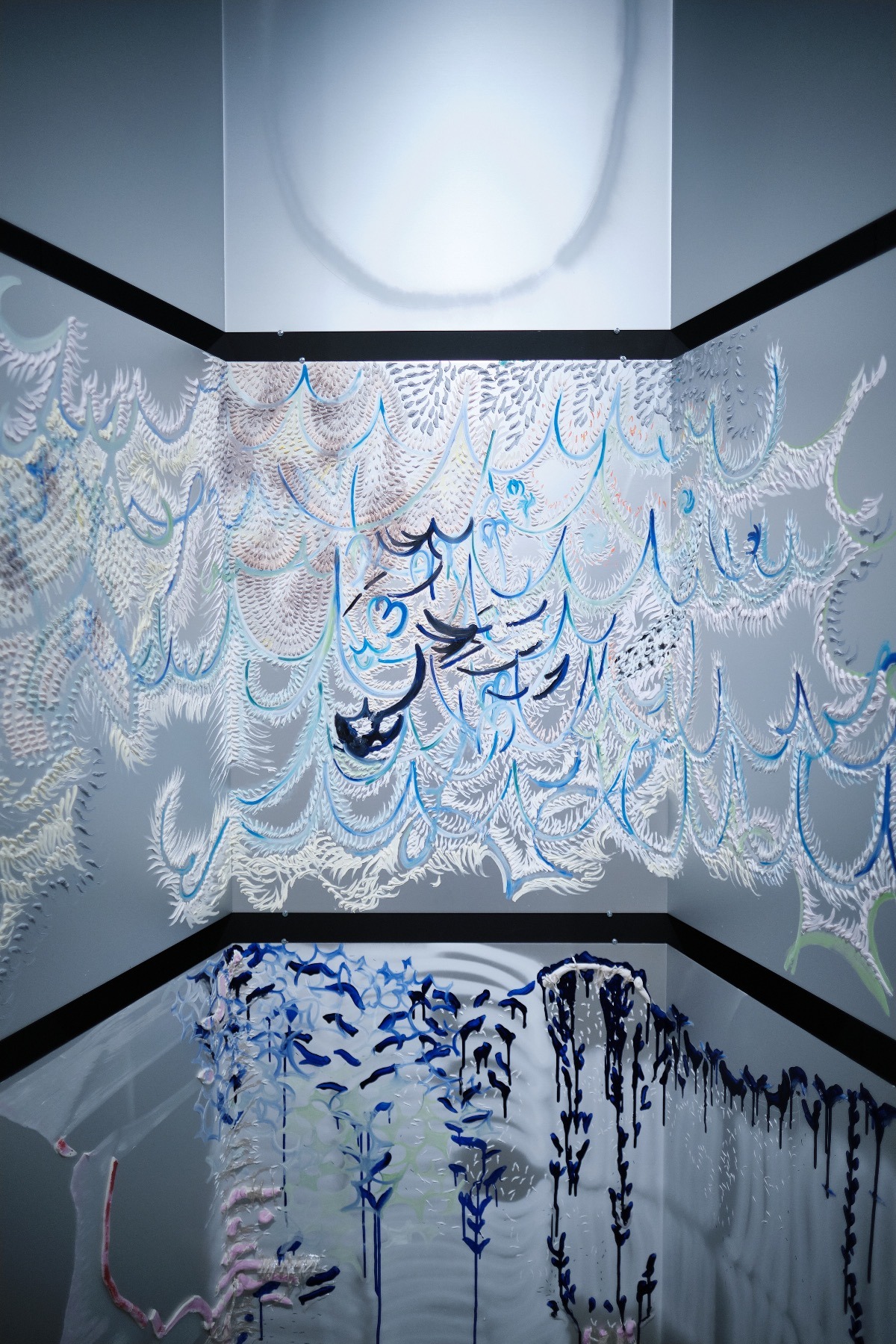

The exhibition was described as an installation-labyrinth. At Riga Art Space, it consisted of more than 200 objects – paintings and sculptural formations. I think the primary medium there was painting, however – the kind that went beyond a strict framework and became spatial, sculptural. What role does painting play in today’s art scene? How has it transformed (if at all)? And are you a painter?

I was pleasantly surprised by Santa Hirša’s review in the Diena newspaper, and I quote: ‘The combination of these [painting elements] and the final result does not resemble an architectural model; instead, it returns once again to a composition similar to a pointillist image made up of spatialised brushstrokes – colour as both substance and matter.

Walking around the exhibition hall, it is not really possible to walk around the individual works or to change your perspective and look at them from all sides, as it is possible, for example, with sculpture or classical installation art. Consequently, the Bunny Bathhouse paradoxically remains flat while, at the same time, it expands into the space.’

The original horizontal plaster platforms that I unveiled in 2014 were also made both as miniature compressed worlds and as flat images. Information seems to become lost in one of the dimensions, simultaneously being there and taking part in the organisation of multiple

perspectives.

The materiality of art is something that has always been important to you. A thick ‘worm’ of paint placed upon the smooth, mirrored surface of aluminium or transparent plastic, for example. Why is aluminium one of your most used planes/platforms? It’s very smooth and flat, but at the same time, its colour is three-dimensional. And why do you use objects made of thin plaster that has been curved into labyrinths or undulating shapes?

There are several answers here. One of them is that simply more aluminium works were exhibited than works in other materials, such as the the aforementioned plaster works (2014–2017), which were more reminiscent of archaeological or resource excavation settings. The other answer is that in transitioning from horizontal plane-paintings to classically vertical ones (i.e. walls), one of the fundamental changes was taking account of gravity, which most clearly revealed itself in the stabilisation of the sliding brushstroke ‘worms’ on a vertical surface. Stainless steel associates more with medical ‘fears’. Each material has its own spectrum of use and meaning-association; in every environment in which I exhibit, the appearance of the works is transformed by synchronising with the states of the outside world, which I then translate into the material and my own positions...

or with what I choose to amplify.

The number of answers I could give you would go up to 20 if we had more time to talk. It should also be noted that I don’t come up with ideas, I just solve them. The ideas just present themselves and then look for an executor. The more the executor listens, the more they give of themself and offer innovative solutions...and the more more clients appear – at least in the world of ideas.

To what extent do you feel attracted to the most canonical art movements – such as minimalism, abstract expressionism, and post-minimalism – the latter being mentioned quite often when talking about your art and its language? Are you aware of your closeness to art history, or do you feel separated from it?

One could just as well analyse whether I am more a victim of the finishes and trims of the Baroque or the Renaissance Rococo. Or whether my first horizontal ‘extruded’ paintings in plaster (2014) – where the paint that was applied at a thickness of one centimetre could contain multitudes (i.e. many perspectives) – were examples of the early Romanesque, or rather, more flamingly Gothic in their construction. To me, art history is more like a Menu than a Bible.

What is the role of art in today’s society – can it speak the truth, and should it do so? And what are you thinking about these days?

Yes, why not set high standards? The truth is often linked with how many lies we are willing to acknowledge, both individually and as a mechanism operating within a community. One effective means of acknowledging lies is to neither absolutise them, nor associate them with one’s own identity, but rather treat them as flowing states of an uncontrolled mind – they are not an identity, but a choice that has not been reflected upon. Eventually, there accrues a sum of choices not reflected upon, a percentile against the vector of other choices, which can be seen as as a streaming set that characterises the individual. Therefore, you don’t have to hide the truth from yourself, because the lie does not belong to you. I think my mind is often small and stupid, and I would like to improve this situation.

Throughout art history, out of the many expressions on the theme of the apocalypse, which do you find closest to your heart?

I have never had a particular sentiment for watching the world come to an end. I would rather see all people come together, cast aside hatred, envy and greed, and use technological advances to realise incredibly beautiful and intelligent environments for themselves and plants and animals to live in. Flames can, of course, be beautifully and interestingly painted, but I would rather see the application of new electric-biological materials put in use towards outstanding new engineering structures and habitable surfaces. Mixed, of course, with natural materials that have been obtained without destroying some other distant land.

What will be left of today’s art after the apocalypse?

If I imagine that 80 % has been washed away, and I set up house in a warm place in the underbrush where garbage has washed up, then it is likely that the most refined trade-language that people will be left with will be the ability to poetically work with found ready-mades, creating jokes, intonations and meanings. Perhaps the legacy of conceptualism will have made these statements more concise. The wave of ceramics and textiles we’ve seen in recent years will produce some of the richest tradesmen of the surviving community. And overall, fewer people will be gullible – for they will now know how creating an illusion on the other side of a phone screen works.

[1] Zaķīšu pirtiņa is a classic children’s poem written by Vilis Plūdons and published in 1935.