A hammer drops, striking some wires...

A conversation with Krišs Salmanis / shortlisted for the Purvītis Prize 2025

...And then music plays. Why did artist Krišs Salmanis come up with this idea, and what does it mean? I spoke to Salmanis about his exhibition Rūgts (Bitter), which took place at the Kim?Contemporary Art Centre from 5 May to 11 June 2023. From 12 April to 8 June of this year, Bitter will be on view at the Latvian National Museum of Art, as part of the special exhibition of works by the candidates for the 2025 PURVĪTIS PRIZE.

Krišs Salmanis creates things slash ideas, things slash preconceived notions, and things slash performances. He paints not with paint but with objects that seem both real and unreal – as if sourced from dreams or long-forgotten memories. He puts firecrackers in red petrol cans, his vinyl-framed windows are in the shape of the five-pointed Soviet star, and he exhibits panels of plasterboard as abstract paintings. Salmanis works with a variety of mediums, including video, animation, and children’s book illustration. In 2013, together with Kaspars Podnieks, he represented Latvia at the Venice Biennale, and in 2015 he received the Purvītis Prize for the exhibition Dziesma (Song), which he created together with his sister, artist Anna Salmanis, and composer Kristaps Pētersons. I also had the opportunity to collaborate with Salmanis when he created the video works and set design for Edgars Mākens’ opera Kontakts (Contact) at the Ģertrūdes ielas teātris theatre, for which I wrote the libretto. It was 2021, the pandemic hadn’t yet settled down, but at least it didn’t seem as scary and unpredictable as in did the spring of 2020. There was a feeling that we just might emerge from this global challenge wiser and more supportive of each other. Everyone was looking forward to the next stage of AI – which was also the subject of Contact.

But then 2022 came, and the 21st century suddenly fell back into the 20th century – or rather, it turned out that the 20th century had never really gone away. And this was exactly the subject of Krišs Salmanis’ exhibition Bitter at the KIM? Contemporary Art Centre. We met up for the following interview in the offices of the Orbīta cultural group – in the same building that houses the Ģertrūdes ielas teātris theatre, and where we held rehearsals four years ago.

All-Terrain Vehicle. 2023. Fabric on board / Latvian National Museum of Art collection

In preparation for this conversation, I looked at what Arterritory has written about you at various points in time. In an interview in 2013, Anna Iltnere discussed with you the notion of ‘the abnormally normal’ (the title of the piece was The Abnormally Normal Salmanis). At the time, you said: ‘Art has gone through complete expressionism, then dry conceptualism, and now a balance is being sought. Maybe the time is right because before, it just wasn’t interesting – who was attracted to the idea of being “normal”?’ In another interview (2017), you call yourself ‘maybe an emotional conceptualist’. Has anything changed since then in how you define yourself?

Nothing seems to have changed that much about normality. As a person, I’m so normal that I’m not very interesting, but now it’s so interesting around me that I can’t complain. The further all this craziness goes around, the more it seems that artists have now taken on a different role. Artists used to be seen as the ones doing crazy things, right? They were written about in books and so on. But now I have hope in artists and cultural workers – that they are the ones who are still trying to sort the world out somehow and make it more normal, or at least create that feeling for a while…like when you go into an exhibition, and you see that...

...everything is in order.

Yes, the artworks are arranged with some kind of thought, and the works themselves are an accumulation of different thoughts and experiences – whether it’s a painting, a sound, or some event – but it’s something concentrated and organised.

Of course, I feel it best when I go to a classical music or symphony concert. Lately we’ve been going to these kinds of concerts more often than to other kinds. And then you get the feeling that there’s this orchestra sitting or standing on the stage, with weird pieces of wood adapted for playing – they’re moving bows along strings, maybe hitting something, or blowing into some other thing. They’re organising the air around them, and that air comes over me in waves.

Organised...

Yes; in a very organised way, these molecules are pushing at me and trying to organise me a little bit.

And they often succeed. I listen and I think – at least in this room, with these people, everything is fine for now. Everything’s fine with their heads, at least...

I think you also quite often have the desire to completely change the flow for a while. When you go take part in artist residencies – in the US, China – you’re swimming in completely different waves. And this gives you new ideas again, perhaps about how to structure the flow a little bit, organise it, show it visually.

It’s probably also because I think I’m quite boring. It’s interesting for me to look at other people who are, maybe, if not more interesting, at least different from me. It somehow revives my joie de vivre and, of course, it also gives me some inspiration.

Construction. Exhibition view at the Alma Gallery, 2021

The time you spent in China had a big influence on your exhibitions that came directly after that experience.

Yes, that could be. But it doesn’t bother me anymore. It used to worry me, but if you look at them and put them side by side, the two ‘Chinese works’ are quite different from each other. You can’t tell just by looking at them that they’re by the same artist. But since I’m not really going to ‘break into’ the big galleries anymore, where you have to have your own very clear visual brand, I make things that are cool and that interest me.

I was thinking more about the fact that you are very reactive to the environment, and so it might be interesting for you to change your environment – just to have more new reactions.

I have a little ‘cheat-sheet’ for myself: if I think that everything is very good and fine where I am, and I’m not really yearning for anything, I need to quickly go somewhere else – because I’m too used to things and I’ve become too boring even by my own standards. That’s why these residencies are a wonderful opportunity to see something different. I go to China or the middle of the US, I live there for a couple of months, and I don’t become less of a Latvian artist. I’m just a Latvian artist who sees other, different things...nonetheless, I can’t do things any other way than as a Latvian.

Yes, but a change in environment can be something else than just going abroad. In terms of the exhibition that we’re going to talk about, it all began with the time you spent in the countryside during the pandemic. And that was a different environment, with different impressions and different thoughts.

I remember that back then, Arterritory had this column: a quick interview with an artist about where they are and what they are doing. Indriķis Ģelzis had a wonderful video from New York in which he goes up to the roof of a building, saying: ‘Hopefully, I won’t set off an alarm!’ And the video ends with an alarm going off.

I thought I was going to live in Bernāti[1] and treat it as a residency. Of course, a residency is also about being away from your family, but I was there with my whole family, and life went on as usual. The impressions from that time – only later, perhaps – turned into this exhibition.

I’m half used to the fact that the first month in a residency is filled with worry and dread, and nothing comes to mind. Then, for a month and a half, something emerges out of its own accord; and then at the end, everything is fine and you make something that you like. In Bernāti, it didn’t work that way for a while, and there were altogether other circumstances due to the pandemic.

The Old One. 2023. A historical window / Museum of Contemporary Art Kiasma (Finland) collection

Did that time of self-isolation and all kinds of strict rules make any impression on you at all?

Two things have stayed with me. The first is a conversation with Mārtiņš Vizbulis. We were chatting about the pandemic and laughing – how some artists tap elbows with each other as a greeting, while others just say hello from a distance. Then we agreed that it was probably a test, because there was a feeling in the world at that time that war might break out. Then we had a pandemic to remind us that, actually, there’s no need to go to war – just deal with the pandemic, calm down, and then try to rebuild some kind of a sensible world.

And then Viesturs Kairišs wrote (or said in an interview) that judging by the way we are behaving in the pandemic, and by the way our public opinion is already divided on whether we should get vaccinated or not, he is afraid to imagine what would happen if something even crazier were to suddenly happen. He was also alluding to a war. And that war did come, and the pandemic had done nothing to prepare us.

So, I am a little disappointed in the pandemic’s performance.

Irradiation, 2023. Plywood, paint, spray foam

I understand that for you, that period gave you the impetus to think about the consequences of post-Sovietism, and what still remains of that time around us.

Yes... In general, I’m very lucky. I was born at the right time to know what it was like in the Soviet Union, but not to be so entrenched in it as to be particularly nostalgic about it. I was just young enough to get away for secondary school – I went to an all-boys school in England. After that, I was convinced that I had nothing to do with that ‘post-Soviet human’.

And then during the pandemic, living in the countryside, my partner and I would take the children on nature walks. And in the middle of all that beautiful nature, you still see those white-brick pig farms with collapsed roofs, or dilapidated grain elevators, or suddenly – three-storey apartment blocks in the middle of nowhere… In the countryside, where there are quaint farmsteads and beautiful scenery all around! It’s surreal! And we would just walk on and continue chatting, until I realised that I was just accepting the situation as nothing out of the ordinary. I was so used to it, since childhood, that it was just…there. For at least 50 years now.

And then it came to me that this ‘post-Soviet human’ is also inside of me – and he is all around me. In the beginning, I wrote it all off to the fact that we [Latvians] are poor. That’s why [in Riga], each of the flats in an Art Nouveau building has their own kind of vinyl window frames that are disproportionate to the original window opening, with the resulting gaps just filled in with blocks of construction material. Everybody renovates as best they can…some have put in brown vinyl window frames, while others have put in white ones. But maybe it’s not all that difficult to at least coordinate with the neighbours, and if your neighbour has already done their windows, to put in the same kind. You can write it off as some kind of historical Latvian need for detachment and doing it on your own – ‘I’ll do things the way I want to!’ But I think it’s also partly the principle of ‘divide and conquer’, which is a holdover from the Soviet era. It was not in the interests of the rulers that people communicate and cooperate with each other. In Ukraine, if I understand correctly, a big part of their strong sense of resistance is that they have horizontal cooperation – they have networks of friends and families who support each other all the time.

I think cooperation is more difficult for us.

Victory, 2017. Animation still

But Ukraine also had a Soviet past.

I don’t know…maybe they’re just friendlier with each other. I can’t explain it.

It really is a good question. The Finns are supposedly even colder and more withdrawn than us, so how do they manage to communicate, to coordinate everything with each other...

What does this post-Soviet type of thinking really mean?

I think that, at least here, it means that, ‘I am more important than you, and my family is more important than your family’. This way of thinking expresses itself very well on the roads. If you drive at the speed limit, and don’t straddle the shoulder while doing so, you’re ‘a fool’ because you’re not fitting in with the flow.

We still need to learn that, at the end of the day, the public good is also our own good.

You have lived in America, at least for a few months – do you think that this kind of thinking is more common there?

That’s also a good question. Because there, the concept of: ‘I have an idea, maybe it will make me rich,’ is even stronger than it is here.

Maybe ‘the American dream’ is the substance that pulls everything together?

Over there, there’s the factor that if you have an idea and it’s clear that you can’t do it alone, you need to find someone who can invest in your idea, someone who can then implement it, someone who will sell it, and someone who will buy it. There has to be collaboration with people. Maybe ‘the American dream’ is also something that unites. It seems terribly materialistic, but there are also wonderful cultural things and collaborations in the USA.

31.12.2022.23:00, 2023. Fireworks in a jerrycan / VV Foundation collection

As I understand from the description of the exhibition, New Year’s Eve from 2022 to 2023 was also very important for you.

At midnight according to Moscow time [11:00 p.m. in Latvia], once again, people were setting off fireworks. It was also the year when everyone agreed that we wouldn’t do fireworks this New Year’s Eve, because there are a lot of Ukrainian refugees here and they flinch at the sound of every shot, don’t they? Secondly, there is nothing to celebrate when there is such madness going on. But then, of course, it turned out that ‘everyone’ was just the group of like-minded people in my spouse’s Twitter bubble.

I remember that there were also calls in the media not to not set off fireworks that year.

Yes, I also saw that request somewhere besides the social networks. But I was quite shocked that after such a terrible year, someone could still celebrate midnight according to Moscow time. Until that year, I had tried to comfort myself with the fact that even though the neighbours were setting off fireworks at 11:00 p.m., I would also see the same neighbours setting them off at midnight, our time. Before the war, maybe it was possible to assume that they were celebrating both their ethnic roots and where they now live – the more reasons to celebrate, the better, right? But in 2022, I didn’t think there was anything to celebrate. But, of course, at midnight, the fireworks went off as usual...and even more than there had been at 11:00 p.m. [Takes on a sarcastic tone] It’s not as if there’s anything to worry about any longer – Ukrainian refugees, dogs, birds, the fact that it harms the environment...or that it is simply no longer a cool thing to do?

The booming noises didn’t let me sleep. It kind of felt like I had rockets exploding inside of me – boom! It was such a disgusting feeling. Then there was this ‘click’ in my head, and I first thought of the red petrol can. On our next trip to the countryside, my dad and I put firecrackers into a metal petrol can. We lit them, and like little boys, we piled rocks on top of the can to keep it from going up in the air and ran away. There was a wonderful ‘POP!’, and we both had such a good time. It turned out to be the same with everything else, too... Absolutely every piece that seemed to have come from a bad start, I liked, and in the end, I liked the show and I felt better. It was completely banal – the art had been a rather healing event for me, more or less.

The Window to Europe, 2023. PVC window / Latvian National Museum of Art collection

When did you get the idea to make a star from vinyl window frames?

You know, I predict that in the next municipal elections, it will once again be popular among politicians to say that we are nevertheless ‘a bridge’...that we have to cultivate communication with the East...that we cannot live without transit, and that the concept of Latvia being ‘a window to Europe’ will return. Well, if we want to be that kind of a liminal pass-through place, then we really will end up like a cheap roadside pub and motel.

And of course, as with all these things, I just wanted to make one.

Biiter. Exhibition view at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre, 2023

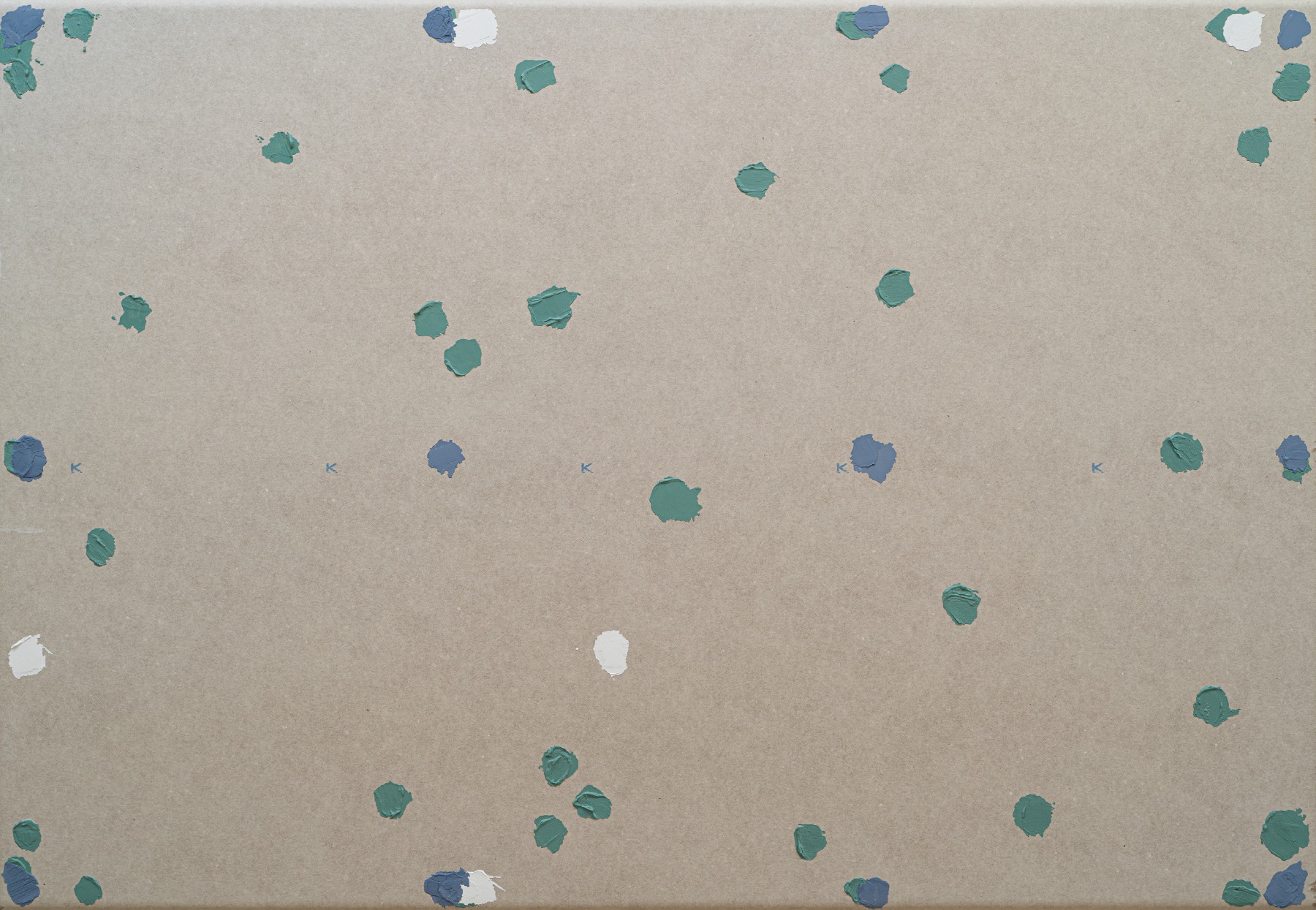

You had a lot of other, as we say, euro-renovation[2] material in the exhibition: plasterboard paintings...

Sometimes I really don’t like something for a very long time. For example, a colour. When I worked in the National Opera in the late 1990s, I noticed that the public usually came dressed in dark greys and browns. But if the ladies got seriously dressed up, they’d wear this bright bluish-green colour. Probably because it was the only bright colour you could really get at the time. Before that, it was this shade of purple, and then this bluish green. I didn’t like it very much, but I ended up gifting my sister a jumper like that, and I ended up liking it myself. It was like forcing myself to like it. It was the same with plasterboard.

When we were renovating the apartment, I tried to avoid it, but I eventually realised that [the Latvian vernacular for plasterboard] is an abbreviation of ‘Rīgas ģipsis’[3]. And it’s probably not such a bad material either – it’s made from plaster and paper, both natural materials. That’s how I started to come to like plasterboard. I just liked what happens when you screw it on the wall, and then you fill the screw holes with spackling paste, and all you see are small tinted dots – it’s very minimal. A kind of ‘abstract painting’ that most carpenters are not even aware that they have painted. I thought that I could make paintings like that, too.

Breath. 2023. Putty on plasterboard, aluminium

You also had ‘clothes’.

This was also an observation from life. I remember a conversation when I was still a student at the Art Academy – [art critic] Kaspars Vanags had come to talk to us, and at one point he threw out this term: Purvciems Versace.[4]

This has stayed with me for 30 years. Maybe it was just a phase of the slow economic development in the 1990s, and when the nouveau riche showed up, they wanted to show off as much as possible – brag about how much they earned, drive around in a Bentley, etc. Those who weren’t in this nouveau riche class wanted to at least look like they were, and so they’d buy a shirt with an Armani logo on it. Never mind that this person would then set off fireworks at 11:00 pm on New Year’s Eve, in the hope that ‘his president’ was in Moscow, not here. I thought that this discordance, or rather the accordance, was amazing – that you can pine for the Soviet Union but long for the Western quality of life – and actually be enjoying that Western freedom of going to the polls and casting your vote for whom you like, rather than voting for one party because there is no other.

That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet, 2023. Field jackets, Armani labels, price tags, framed sketches / Latvian National Museum of Art collection

But you have lived in China, where there is one political party and all the most luxurious brands, and they all fit together in a way that is, admittedly, not very clear to us.

Somehow it just doesn’t click for me. So I tried to create things where it all came together. I still have my dad’s authentic ‘vatnik’[5] at our country home. Maybe he brought it home from the army. But I decided that I wanted to make vatniks that look nice and fashionable, with Armani tags – although they’re still really nothing more than just a vatnik. And they should have really long arms, so that they could stumblingly still chase after you, even without any legs, as they try to defeat you or claim you for their own. When they were made, I liked them. They’re nice.

Waltz No2, 2023. Hammer, motor, electronics

Tell me about the installation called Otrais valsis (The Second Waltz).

I’ve always liked that musical piece.. It turns out that Shostakovich’s Second Waltz comes from a work called The Suite for Jazz Orchestra No.2 [1938]. I’ll tell you how I found that to be funny: imagine the 1930s in the Soviet Union – the Stalin era...and jazz. You can’t really hear the jazz in it, but at least it’s in the title.

Could you explain how the mechanism in the piece works?

There is a hammer that goes up, and then it is released and the hammerhead strikes the ground; since the hammer is made of metal, upon touching the ground it connects the two ends of a wire. This then sends a signal to turn on the music that plays on a speaker. Then the hammer goes up again and the connection is broken. Silence. And then it repeats.

You want to know what do I mean by the artwork, how do I understand it, and why did I put it together the way I did? Well, I would go into the exhibition space every once in while to tweak or check something, and sometimes I would meet exhibition visitors, some of whom had such good comments that now I don’t remember what I was thinking when I came up with it. [Art historian] Inga Šteimane had come, and she said she liked the hammer because it reminded her of her childhood, when she had to go to music school and she was taught that opera as such began with Glinka[6], that Soviet composers were the best, and no one else really mattered. That was not my experience because I didn’t go to music school, and I don’t really understand any of it, but I thought that interpretation was more direct and more accurate than what I had thought of when I started on the work.

For me, this melody is the perfect embodiment of nostalgia for the Soviet era. When I hear this music, I see in my mind’s eye fuzzy scenes of a film in which Soviet officers are waltzing – so gallant, so dashing – with women in flowery dresses and the spring sun is shining...something like that.

With music by Shostakovich? Do you think that could have really happened?

I don’t know. But that’s what that waltz sounds like to me. I know that intelligent people can hear Shostakovich’s opposition to the existing regime in the piece, but I don’t hear it in this waltz. And then I thought that, combined with some kind of awful banging noise and that brutal hammer, it might express the contradiction I feel...

An excellent example of this phenomenon took place during another artist residency, this time in Finland, and at this one you had to talk about your work. [Latvian artist] Katrīna Neiburga was also there; she was talking about her work to the Finns, and she mentioned that she had a happy childhood. But the Finns refused to understand – how could someone have a happy childhood in the Soviet Union? So, perhaps this work is also about the fact that I, too, had a happy childhood. Most likely not because of the Soviet Union per se, but because I had both parents and a cool sister, and everything was good...I had a good childhood. But children are probably playing in Afghanistan, too...and in Ukraine. Maybe they will also someday remember something happy and bright from their childhood, but nobody will believe them and they will will be told that they must be traumatised. Clearly, they will be, but...

And so it seems to me that the hammer and the beautiful music also somehow express that contradiction. Maybe this one is finally something that is not so ‘abnormally normal’; maybe this work is a bit more complex.

Normally abnormal.

Yes.

Biiter. Exhibition view at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre, 2023

I think you generally like to make real contraptions that move and do something. Did you make anything like that as a child?

I had a toy construction set. You probably also had one.

Of course I did! But I never really did anything much with it.

They came with instruction books, but I didn’t follow those. At that time, I liked to just screw things apart and together, and it wasn’t complicated, of course. But I liked tinkering. The little screws did as I told them, and there were some electric motors as well. My grandfather, for example, gave me an electric toy car that had a controller with a couple of buttons connected to it by a wire (we didn’t have radio remote control toys at the time). Granddad had not yet left my birthday party when I had already decided to find out how the toy worked. I remember screwing open the controller and taking out the wires, thinking that I’d know how to put it all back together...but I didn’t. Of course, Granddad was both disappointed and angry, but eventually, I had collected several electric motors from such events. But this apparatus I invented myself, and then I told Oskars from set design what I needed to make it. I think he had constructor sets when he was a kid, too, and he likes trying to figure out how to make things work. But in the case of the hammer, I made a little model out of cardboard and then my partner’s dad made the real thing for me.

I see you have your own ‘American dream’, where everyone has to work together...

Yes, this is how cooperation works.

More than a year has passed. Would you change anything in the exhibition?

No, it’s a whole, one where everything is solved and perfectly in the right place. I keep thinking about the next works I will make, and I want to do another exhibition. A kind of continuation of all this.

What will you be drawn to next? What do you want to do now?

I have already acquired taxidermy materials. I have to ‘release’ a dead bird I found in the yard. It must have flown into a window. It was still warm...a bullfinch. For a long time, I looked for someone who could stuff him, because I want to do another work with a vinyl-framed window but with this bullfinch in it. Imagine the bird boldly flying, straight into the window, and then...it’s all over. But I want to make a work where the bird has flown into the window – and beaten it. The window has broken into shards, and the bullfinch is standing there like an eagle, spreading his wings...like the winner...maybe even putting a leg up on the ‘defeated’ window.

That’s the power of art!

This is the artwork I want to make with the little bird so that, even if he is dead, at least he has won. I first looked for a taxidermist who could do it respectfully and professionally, but I guess little birds like this are too tiny and fussy, and nobody really wanted to do it. And then I thought, I’m an artist, I studied model-making at the Academy. I could probably stuff a little bird. That’s kind of my plan for the immediate future.

I remember in one of your older interviews, there was a question about ‘saving the world’. And you said at the time that you didn’t see art having any sort of mission to save the world. Yet you are interested in saving this bird.

A long time ago, a friend of mine said: ‘Krišs, you will lose your life in the details’. I still have a little notebook where I write down, in tiny little letters, everything I need to do. Maybe someday there will be something grand, something big, something lasting and profound that I might do, but in the meantime, I do little things – this little bird, little daubs of spackle on plasterboard...

About that bird… maybe it’s because you want that justice, that unwinnable victory?

Yes, and this may finally answer your first question, about ‘the emotional conceptualist’. Since that interview, I’ve probably become just a little bit more emotional. That’s what my wife tells me – ‘You’re sentimental’. Fair enough.

I simply create an artwork, but I make the sentimental or emotional aspects so minimal that it looks conceptual.

What you do often looks like models of ideas, or models of beliefs/viewpoints, but the solution is always very...perhaps not warm, but strong enough to evoke emotions.

Oh...I like that.

***

[1] Bernāti is a countryside village where Salmanis has a holiday home.

[2] The term ‘euro-renovation’ originated in the mid-90s within the construction industry in the post-Soviet space – contractors would encourage buyers to invest in ‘European-standard’ materials and solutions, using the prefix ‘euro’ as a symbol of quality.

[3] In 1938, the Rīgas ģipsis plaster company started producing plasterboard sheets used in dry construction.

[4] Purvciems is a working-class suburb of Riga with a high population of ethnic Russians.

[5] A vatnik is a Russian padded jacket made from cotton wool.

[6] Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka (1804–1857) was the first Russian composer to gain wide recognition within his own country and is often regarded as the fountainhead of Russian classical music.