A pagan’s prayer

A conversation with Ieva Kraule-Kūna / shortlisted for the Purvītis Prize 2025

Ieva Kraule-Kūna’s exhibition Rīma (Glutton) was on show at the 427 gallery in autumn 2024. Actually, Glutton could also be called the artist’s private diary entries or reflections prompted by her move from the city to the countryside, where, as Kraule-Kūna says, she has ‘a greater need for sunny days and less for cute shoes’.

Kraule-Kūna studied in the Ceramics Programme at the Riga School of Design and Art, then in the Department of Visual Communication at the Art Academy of Latvia, as well as at the Sandberg Institute in Amsterdam.

She is one of eight candidates nominated for the 2025 PURVĪTIS PRIZE. Her exhibition Glutton will be on view as part of the Purvītis Prize finalists’ show at the Latvian National Museum of Art from April 12 through June 8, 2025.

What is the story behind Glutton? The exhibition appears very poetic in its execution, although the word ‘glutton’ is not exactly romantic, and the narrative of the exhibition revolves around the fact that we need a lot of everything and increasingly more of it – it’s about our desire to consume.

It’s the story of how I moved from living in the city to living in the suburbs, which are physically very close but at the same time, very far – it’s like the countryside here, with cows grazing across the road from me. My studio differs from contemporary artists’ studios, which are usually heated industrial spaces. In my studio, it’s almost like being outside – it has a roof and walls, but no heating. All of this – the cycles of nature – affects the rhythm of my work. I can’t work in winter because it’s too cold, and if it’s too hot, I also can’t work. So, the making of all the big objects in the exhibition was very much conditional to what was happening in nature. What the weather was like – whether it was wet or dry.

It had nothing to do with the city and its current events, so there was a kind of distancing from the life of consuming. A feeling that I can look at it all from the outside, and not be so gluttonous myself… at least not so very. That’s because I have a greater need for sunny days and less for cute shoes. Because I live in the countryside, I rarely get to go to a party where I would need those shoes. But at the same time, exhibition deadlines are always coming up and I’m becoming increasingly more dependent on the weather. I’m becoming almost primitive, ready to pray that it will be dry enough and that the clay objects will dry out...that they don’t collapse from their own weight...so that I can work faster. It was not all up to me. When the sun shone, I could ‘build’ ten centimetres a day. But when it rained for three days in a row, I couldn’t manage more than two. And so the process becomes a pagan’s prayer because it is the only way I can have any influence on it...to receive the grace to work.

And then the ‘gluttony’ becomes different. The objects are a cry for nature’s favour, and at the same time, an affirmation that everything else is unimportant. If you can’t do what you have to do, everything else is unnecessary and superfluous. And it is at that moment that you realise that back when you thought you desperately needed the latest shoes and the chicest dress and the car and everything else – maybe it really wasn’t so important back then either. It was just that the comfortable conditions that you had made you look for what seemed to be missing. Trying to fill the void with things. Creating problems where there were none. Because everyone has emptiness, and it makes a thinking person act – something is missing, something has to be filled and completed. Only, sometimes, you lose focus and it starts to feel like you should start filling with material things, when in fact, it is something else that you have to fill yourself with.

The characters in this exhibition are not the most popular figures found in contemporary art stories – pumpkins and courgettes, firewood and ears of corn.

That’s true. In my context, pumpkins and courgettes are associated with loneliness. Once I had a daughter, I became even more isolated because most of my artist friends don’t have children. There are very few children in my immediate circle. It created a kind of gap – I couldn’t go to parties on weeknights and have a nightlife because I had other responsibilities. Moving away from the city increased this gap because nobody comes to visit me at noon anymore, just to stop by because it’s convenient, or on their way to somewhere else. I don’t go to many events because the logistics are too complicated, and it doesn’t seem worth it. Homegrown pumpkins and courgettes... friends are always offering them to each other, complaining that they have too many – their granny sent them from the countryside. Nobody offers me any. I have to grow my own. Otherwise there will be no pumpkins, no courgettes. Nobody brings them to me.

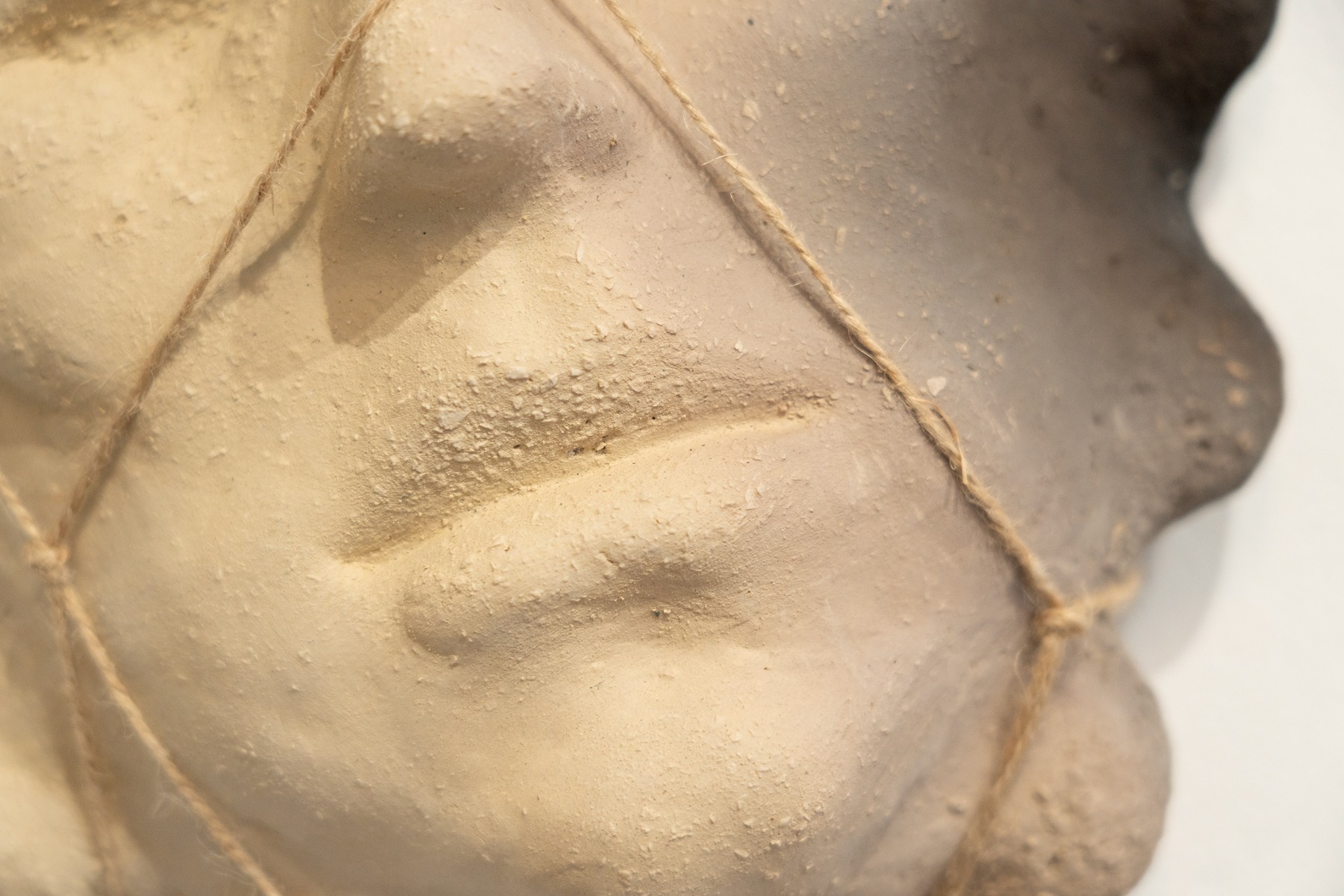

And this exaggerated, even caricatured expression that the pumpkins/courgettes have?

Outwardly, these faces resemble masks, but the story is about what’s inside us; what’s hiding underneath the prettiness. How often in life do people feel beautiful? I don’t know about other people, but I’ll speak for myself: I usually don’t feel beautiful. Either you’re too sad or too immersed or too angry. Everyday life forces you to be normal, reasonable. You have to function in society, you have to do this and that.

Is there any basis in associating these string-tied pumpkin and courgette grimaces with the ubiquitous clay medals[1] that could be found in almost every home during the Soviet era? They were usually hung from a string. I’ve heard they played an important part in the creation of this exhibition.

Throughout my childhood, I had these clay medals hanging above my bed. I didn’t even ask my mother why that was. Knowing me, I probably told her that I liked them, so that’s why they were there. There were all sorts of medals, from sea festivals to folk-dancing groups. It’s not that I was specifically thinking about them... It’s more like they was subconsciously there.

But you’re not a ‘real’ child from the Soviet era.

But I do remember. First of all, things and objects stay around for a long time. It wasn’t as if, in 1991, Coca-Cola vending machines suddenly appeared on every corner. I remember everyday life, and it was different. Interestingly, during the Soviet period, I lived with my mum and grandparents. But when independence came, it was just my mum and I. In the first phase, there was grandma and homemade meals; in the second phase, when I came home from school, I had to make instant noodles for myself because mum was at work. Of course, it was precisely this transition phase that shaped me the most as a person. But it’s strange how there’s this one snap of the fingers, one moment – and the next generation is completely different. They no longer have memories of queues for sausages. For example, my husband has no memory of queuing, whereas I do. I have memories of that world looking different.

This exhibition is like a series of diary entries – could one say that? Feelings and reflections materialised into objects.

Absolutely, and it’s always like that for me. I tell everything about myself through a poetic form. Maybe the viewer doesn’t get it right away. But who wants to go to an exhibition and just hear that I’m lonely, I live in the country, it’s raining, everything is going badly... The viewer looks at these objects through the prism of their own personal experiences, and sees what is important and relevant to them. In fact, they are notes on daily life. Sometimes they are about the past, sometimes (as in this case) they are about the present. And then the critical position, it enters....

...and they are these reflections of yours.

Yes! [Laughs]

And what kind of feelings do objects like giant boots and sheaves of grain encompass?

Boots are the heaviness that you feel when you get out of bed and you don’t want to go anywhere. You can’t get very far. It’s what keeps you tied to the ground. You can put them on, stand up, but then not have the strength to take a single step. The sheaves of grain, on the other hand, are a symbol to be worshipped. Productiveness. Perhaps it comes from those Soviet-era medals?

When I was about 25, I contracted Lyme disease, and one of the lasting effects was rather severe memory damage. Ever since, I’ve had this fear in me – I don’t know what is coming or where it’s coming from. I’m better now, but the feeling remains – that there’s some kind of cache of memories in your subconscious that you pull out and try to put something together. And you’re somewhere to the side of it all, trying to understand where it’s all coming from. Something made me look all over the city for sheaves of grain.

The materiality of this exhibition is based on ceramics – what connects you to the materiality of clay? Why do your hands like to work with it?

Even if I’m making something on the computer, I use a programme that supposedly allows me to make something out of a lump of clay. In fact, the result is very similar to what I make with my hands. I was quite surprised the first time I used it.

But when it comes to ceramics, what is important to me is its unpredictability and contingencies – the weather, the humidity, the temperature. The physical constraints. How thin, how crooked its shape can be. Working with clay the way I do – pinching, smoothing, building with slabs – the material becomes very performative. They are like imprints of a particular moment – just like a tree trunk, where each ring preserves information about what kind of year it was. There’s a moment locked in there that, after it’s dried and fired, becomes almost embalmed. Captured. Preserved.

You deliberately preserve the rough surface of the clay – you don’t try to make it shinier with glazes.

Unglazed clay retains the feeling of an earthy material, while glazed clay immediately ‘brings in’ national romanticism and associations with Latgalian pottery[2] – something completely different. It is no longer the pagan who wove his own tunic.

Do you feel the pagan in you?

Yes. People believe in horoscopes, follow various spiritual practices...but I don’t believe in anything. Nothing in this world. But I am, however, interested in everything to do with the occult, witches, and the primal. I’m not going to dance naked in the dew myself, but I’m very fascinated by it. That’s because it can explain a lot. Through our ancestral customs and primitive cults, we can get to know that part of humans that is detached from the physiological and the material – the very thing that creates modern existential suffering in modern humans.

Do you like having physical contact with the clay?

Yes. For instance, I don’t really like making things out of plasticine. It’s oily; I don’t like it. I like a rougher clay, the kind in which you can feel the grit in it – not the smooth kind.

It’s a calming process for me. Rarely do I have a very clear plan of how it’s all going to be in the end. I take it, I shape it, and ‘it’ comes out depending on the feeling I have at that moment.

But I also like other materials because sometimes I have ideas that require something synthetic. If I want something to be transparent, for example. And I find it interesting to mix materials. Clay has its own story. It is natural; it is the earth. And then there are the synthetic materials that bring modernity into everything...that urban feeling.

Ieva Kraule-Kūna, Elīna Vītola. Artist Crisis Center II-B: Fair Gear. Work in "Black Market" exhibition at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre within the project "Artist Crisis Centre". The work was nominated for the Purvītis Prize 2021. Photo: Ansis Starks

What role does colour play in creating this feeling? Glutton is very subdued, natural. But you also tend to work with vivid, almost luminescent colours. I remember, for example, green and blue masks.

I have different colour palettes for different ideas. When it comes to something intimate, personal, natural, something that is not usually shown to others – it’s beige, white, pink, creamy. But the bright ones are about the outside world. Like the masks I mentioned. Like the clothes you put on to hide. Behind the vivid, the beige disappears.

In this exhibition, alongside objects made of natural materials (including readymades – sheaves of grain, firewood), there’s also video. Compared to the other materials here in your toolbox, it seems a bit alien.

I’ve never really felt the video artist in me. The use of video always comes more out of need. My first video works were made due to the need for text, which I didn’t want to reproduce on sheets of paper. Video was a way to provide intonation and convey information.

In this case, the video is a form of documentation, because I didn’t know if the object, the big ‘Glutton’ itself, would survive. I had never made something so big that I had to fire it from the inside as well. I knew that, technically, it wasn’t correct and that all rules dictated not to do it. So I accepted that it could all fall apart and turn to dust. I recorded it if only to make sure that something of it would remain. But the moment I lit the fire, I realised that the best moment in the existence of this object was the burning itself – how it popped and crackled, how it changed. I have the most complete experience of this exhibition, one that nobody else has seen. You can’t convey that feeling through video. The terrible heat coming out of the flaming mouth, the roar of the fire and the smell of the smoke that was so hard to wash away afterwards.

I hadn’t originally planned to include a video at all. It was more of a contingency in case everything fell apart. But as I lived through the experience, I realised that this was the best moment of this object’s life.

His performance.

Yes. I’m actually a ceramic-slash-performance artist [laughs].

You’ve already touched on the importance of texts, and you write them yourself. Is text also one of your forms of artistic expression?

Yes, definitely. Sometimes text can also be a separate object in an exhibition. But most often it is a way of giving the viewer the keys to enter my world. I probably haven’t yet met ‘my’ curator, one to whom I feel I could entrust this part. But I also like to write. If I did have ‘my’ curator, I could write even more abstractly, completely abandoning the explanatory function and allowing the text to be a self-contained work of art.

Taking on the role of curator has been a part of your artistic practice, however.

Yes, but that was different. I’ve never felt like a curator. In fact, the way I have engaged in the curatorial process is not really ethical – it was more about realising my artistic ideas through other people’s work. Those times that I did curate, I realised how much I didn’t want to do it – that I wanted to be an artist myself. Curating drains your resources, but it doesn’t make me feel fulfilled. Those are other people’s artworks, not mine.

Does the viewer, and their opinion, matter to you? Surveys show that contemporary art is one of the most misunderstood segments of arts and culture.

I suppose the average viewer can get the feeling that they are just not wanted. To some extent, this is also the fault of the art community. The elitism and the desire for champagne and oysters has been stronger than the desire to talk to the viewer. If I sometimes feel uncomfortable when I go to an exhibition opening because I don’t know anybody there, I can understand that it would be simply impossible for an outsider to just walk in.

What can the viewer gain through art?

The realisation that there are values that go beyond everyday life and the daily grind. Art makes existence easier. Otherwise there is only work – so that you can pay the bills and go on an annual holiday. Art says: Look, there is also something strange and unusual in the world! Maybe there is something more than just our mundane responsibilities. Like a psychotherapist, art talks to you about things you are not ready to talk about with someone directly. It gives you a chance to look at everything from the outside, and in this way, you are able to learn and understand something.

Like a pumpkin tied up in string, saying you don’t need new shoes.

You don’t need new shoes, but you need people who care for you and bring you a pumpkin from their garden. So that you are fed.

***

[1] These ‘medals’ were rather rustic ceramic (red clay) discs embossed with pictures, slogans and designs, and served as commemorative souvenirs.

[2] Latgalian pottery is known for its bright, shiny glazes and profuse use of embellishment.