A network of roots that keeps the sand stabilised on a windy day

A conversation with Inga Meldere and Luīze Nežberte about their joint exhibition Sunpoles / shortlisted for the Purvītis Prize 2025

Inga Meldere’s and Luīze Nežberte’s preparation for their joint exhibition Sunpoles took about a year of intensive work (‘I had a quite strict rhythm to which I adhered to via a rather athletic method,’ says Meldere) in the artists’ respective studios in Helsinki and Vienna. The following online conversation between the artists and myself, the curator of the exhibition, took place on October 9, 2024, when both artists had already returned to their home bases outside of Latvia; it provides further insight into the exhibition’s concept, artistic choices, and methods of collaboration.

Inga Meldere and Luīze Nežberte. Exhibition view at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre Photo: Ansis Starks

A couple of years ago, I invited Inga to create a long-awaited solo exhibition at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre, which developed into Inga expressing an interest in bringing Luīze on board and creating a joint exhibition. Inga, what prompted you to develop your solo exhibition into a collaboration and dialogue with Luīze specifically? How do you interrelate with each other’s work?

Inga Meldere: What attracted me to Luīze’s practice was that I associated it with something new and undiscovered. Something that could be described as a kind of interest in romanticism – a new kind of romanticism. I first formulated this term for myself after attending the Venice Biennale in 2017, when German performance artist Anne Imhof received the Golden Lion for her project Faust. Watching her performance and studying her work, I felt that a new kind of visuality and understanding of how art can be talked about and executed was emerging here. Luīze’s artistic practice is successfully moving into this territory – the so-called ‘new romanticism’ – which I also find fascinating. Luīze is interested in things; she is constantly engaging with new kinds of research and exploration; she is open to dialogue with artists and thinkers of various generations, both living and dead. This, in turn, resonated with my own artistic practice, where interests and directions are constantly emerging and changing, and often in interaction with other creative thinkers.

A view from Inga Melder's studio in Helsinki with works in progress. Photo: Inga Meldere

Luīze Nežberte: Even before we met in person, we started to engagingly communicate on Instagram. There was a mutual understanding and trust that brought us closer, and when you live outside of Latvia, it is often valuable to have a like-minded person with whom you can discuss things in a familiar language when observing processes from the outside. We share a mutual interest in history, in playing with reality, in mixing up classifications, and in the fascination of bringing moments of previously forgotten or obscured history to life in a new way.

Inga Meldere and Luīze Nežberte. Exhibition view at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre Photo: Ansis Starks

Turning more specifically to the exhibition, Inga’s invitation to collaborate came with the additional intention of following what Luīze would offer as a starting point – a kind of ‘call and response’ method where the sequence of two different elements lays the foundation for a longer conversation. Luīze’s starting point was a very specific, even marginal, episode of Latvian cultural history linked to the cultural and vernacular architectural heritage left behind by the Moravian Brethren in the 18th–19th centuries. Luīze, what was your initial encounter with what has developed into one of the central cornerstones of the exhibition – the so-called ‘sun columns/poles’ and the legacy of Pauls Kundziņš? And Inga, what was your response to this ‘call’?

L.N.: It began with my conversations with the exhibition’s self-published zine’s graphic designer Stefans Pavlovskis, who is also an architect and worked with Austris Mailītis on the exhibition illustrating the construction of the new Song Festival Stage. Stefan researched archive materials and reconstructed historical stages for the book The Evolution of Latvian Song Festival Structures, 1873–2023[1]. After talking about this history, I visited the pavilion next to the new stage, which is where historical artefacts from past Song Festivals are kept and exhibited.

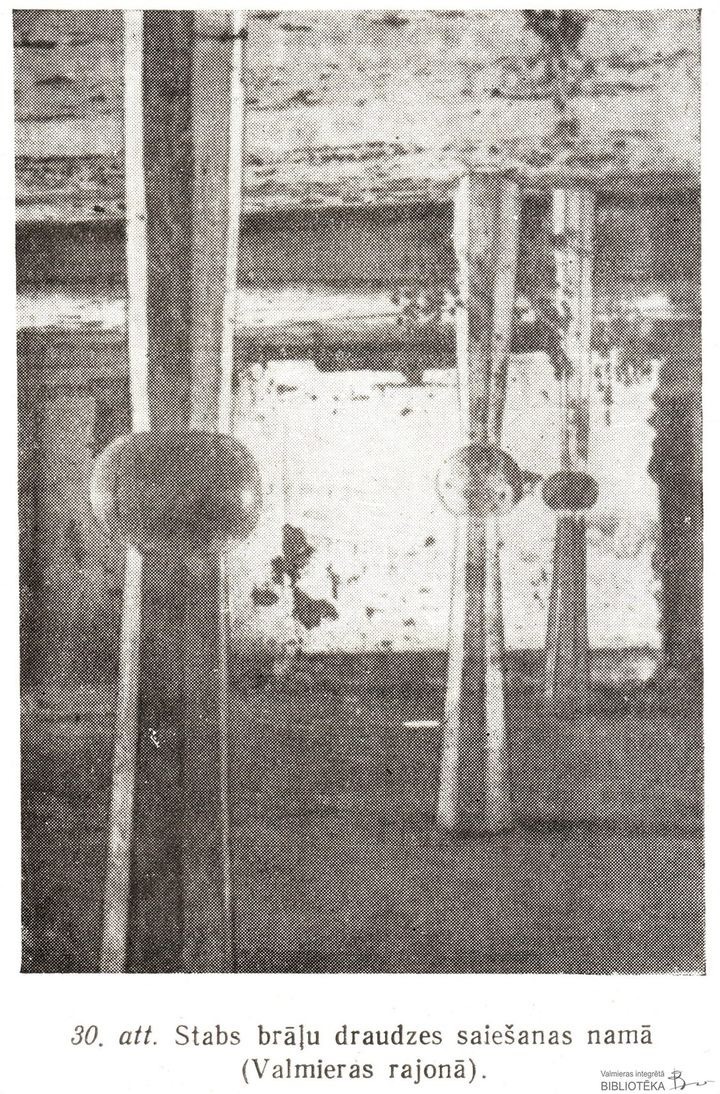

In the exhibition, there was a small model of the 1926 Song Festival column designed by Pauls Kundziņš[2], and I was intrigued by its shape. Then, in the magazine Latvian Architecture[3], I came across an article by Kundziņš on the ‘sun columns’ and the use of vernacular architectural elements. The material was accompanied by a black-and-white photograph of Latvia’s first state-protected cultural monument, the Moravian Brethren Meeting House, built in 1756 in the town of Gaide. I was fascinated by the perimeter columns with their faceted vertical sections radiating upwards and downwards from a central sphere, and which brought to mind the sculptural canon of the Western world – Italian Futurist space-age design of the 1960s and 70s and such. My initial fascination with this shape, which I had inadvertently come upon, turned into a deep-dive into the activities and significant impact that the Moravian Brethren had left on Latvian history. I sent Inga the black-and-white picture of the columns of the meeting house in Gaide, as well as a picture of the columns designed by Pauls Kundziņš. That was how it all started.

Column manufacturing process in Vienna. Photo: Luīze Nežberte

I.M.: I’m also really interested in all of these topics and references, although from a slightly different point of view – less through form and shape, but rather through other kinds of associations, which encouraged me to do a different kind of intuitive research. During one of our conversations, we began talking about the Lithuanian archaeologist and anthropologist Marija Gimbutas (1921–1994) and her research on the Neolithic and Bronze Ages in the Baltic region. Her books interested me, and in them I found answers to various questions that I had been pondering for a long time – for example, a conscious understanding of the historic formation and delineation of the current territory of Latvia. I was interested in the place where I came from; I wanted to explore in more depth a period in history that was not all that clear to me. Although they could all be seen as interpretations of a kind, I have clarified a lot for myself through this research.

Gimbute’s exploration of aspects of the region’s history and geography is also seen as a celebration of the role of women – how the region’s cult of the female/mother-nature laid the foundations for our relatively matriarchal society. I think this fits well with both your individual and shared practices (in regards to the exhibition), all of which are tinged with feminist conviction. Interestingly, your views form a peculiar and evocative tension with the majestic vertical objects (the above-mentioned columns) that were placed around the perimeter of the exhibition. In your interpretation, these inevitably masculine pillars or stanchions – often associated with power, even aggression – become ‘calmer’, ‘more restrained’.

L.N.: I didn’t specifically think about the masculine ‘gesture’ that a column may give off, nevertheless, there undeniably is a well-known culturally and historically loaded message that comes across when you place something vertically oriented into a space. What was important to me was how the ‘sun columns’ would exhibit and react in the given location and architecture of the Kim? space – these sculptures are like ‘coats’ for the existing columns/posts in the Kim? exhibit area. Gimbute specifically wrote about the totems and columns of these ancient tribes; about how, in their perception, ‘the sky above our heads is nothing but a roof held up by these columns’. In my interpretation, this action remains a gesture – the drawing of a line in space that connects these planes of heaven and earth.

I.M.: ‘Dressing’ the columns in ‘coats’ is also a very protective and motherly expression of love.

Computer sketches for the painting "Swallow’s Brood". Photo: Inga Meldere

Turning more to your individual practices and work in the studio, which is invisible to the audience, I’ll first address you, Inga. One of the most obvious approaches in your practice is what you call ‘expanded painting’, in which you increasingly develop and ‘expand’ the work in question. Over the last few years, two distinct pairs of ‘mirroring’ have become clearly discernible in your work. The first case involves pictures you’ve taken on a smartphone – e.g. of a museum in Athens, a bus stop on the outskirts of Helsinki – overlaid with a layer borrowed from various existing sources and references of cultural history and folklore, which are then – to a greater or lesser degree of unrecognisability – reinterpreted by you in a painterly way. In your second case of ‘mirroring’, the very technique of making the works is multi-layered: the UV printing of digitally processed images onto a canvas which is then coated with acrylic and/or oil overlays.

I.M.: As far as ‘expanded painting’ is concerned, I see it as painting on an image that goes beyond the usual starting point, i.e. the applying of paint on a white canvas. The image serves as a starting point for the ‘problem’ that I have to solve through painting. Starting with a white canvas would take longer since it would involve creating the problem, which would then outweigh the process of searching for solutions. Interestingly, this time I had the UV-printed canvases ready, but they had been just standing there, unresolved, because I had come to an impasse with them. The context of the exhibition was the perfect excuse to return to them. All I had to do was congeal the ideas in my head and sit with them. Usually I work with images intuitively – going through archives of images, putting them together, seeing if they click or not, if there's a good follow-up or not, etc. One of the folklore resources I took advantage of was the Digital Repository of the Archives of Latvian Folklore, which I was told about by folklorist and storyteller Ina Celitāne – she is interested in looking for new ways to promote folklore beyond the usual didactic and somewhat traditional approaches.

Inga Meldere and Luīze Nežberte. Exhibition view at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre Photo: Ansis Starks

Another question for Inga regards your smallest works in the exhibition, which belong to a series of a few hundred such works: you began making them during the recent pandemic, and call them a kind of ‘breathing exercise’. Do they contain references and connections to emotional and mental health, self-healing, meditation?

I.M.: Yes, that’s definitely the case. I approach them as a routine for both breath and hand training. I let my hand unconsciously and relaxedly explore the ‘territory’, and only then did I connect my mind and react to the impressions – the strokes, streaks and/or trajectories made by foam rolls – that I had just created on the surface.

Work "Waterlilies" by Inga Meldere at the exhibition at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre. Photo: Ansis Starks

It was almost like the call-and-response method, where the hand makes a suggestion and my mind responds by creating a readable image. The original intention was to create them quickly – as an impulse during one painting session – and never come back to them, but that didn't always work, with some pieces calling for continuation, layering, and finally – a title.

A view of the working process in the studio. Photo: Luīze Nežberte

Luīze, you also deal with the notion of expansion, but specifically in the fields of sculpture, modeling and installation. Could you elaborate on your codework for ‘expanded sculpture’? How do you approach it, and how do you integrate different conceptual gestures and develop them through the use of specific, deliberately chosen materials?

L.N.: For me, in general, sculpture embodies a tension between opposites. It is something that embraces immateriality through relationships, as well as materiality through relationships. Looking back through history, sculpture hasn’t been an artform that instructs or indicates to the viewer which is the ‘correct’ angle from which to look at it. It is the physical experience of looking at the work and finding your own point of view that is important. For me, the interpretative element is always important when thinking about a work because I'm not trying to imitate a historical shape or artefact. I'm interested not only in the shapes and forms, but also in the histories of the materials. The MDF material used in the two columns [in this exhibition] is a deliberate choice because these wood composite panels have an interesting history – MDF was developed as a way to make use of the huge amount of leftover wood chips and shavings that lumber mills discarded. This unpretentious panel of MDF – much like more precious materials, such as marble – carries its own unique material history, and the shift from leftover waste to refined material marks a change in attitude in both the manufacturing and creative industries.

Inga Meldere and Luīze Nežberte. Exhibition view at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre. Photo: Ansis Starks

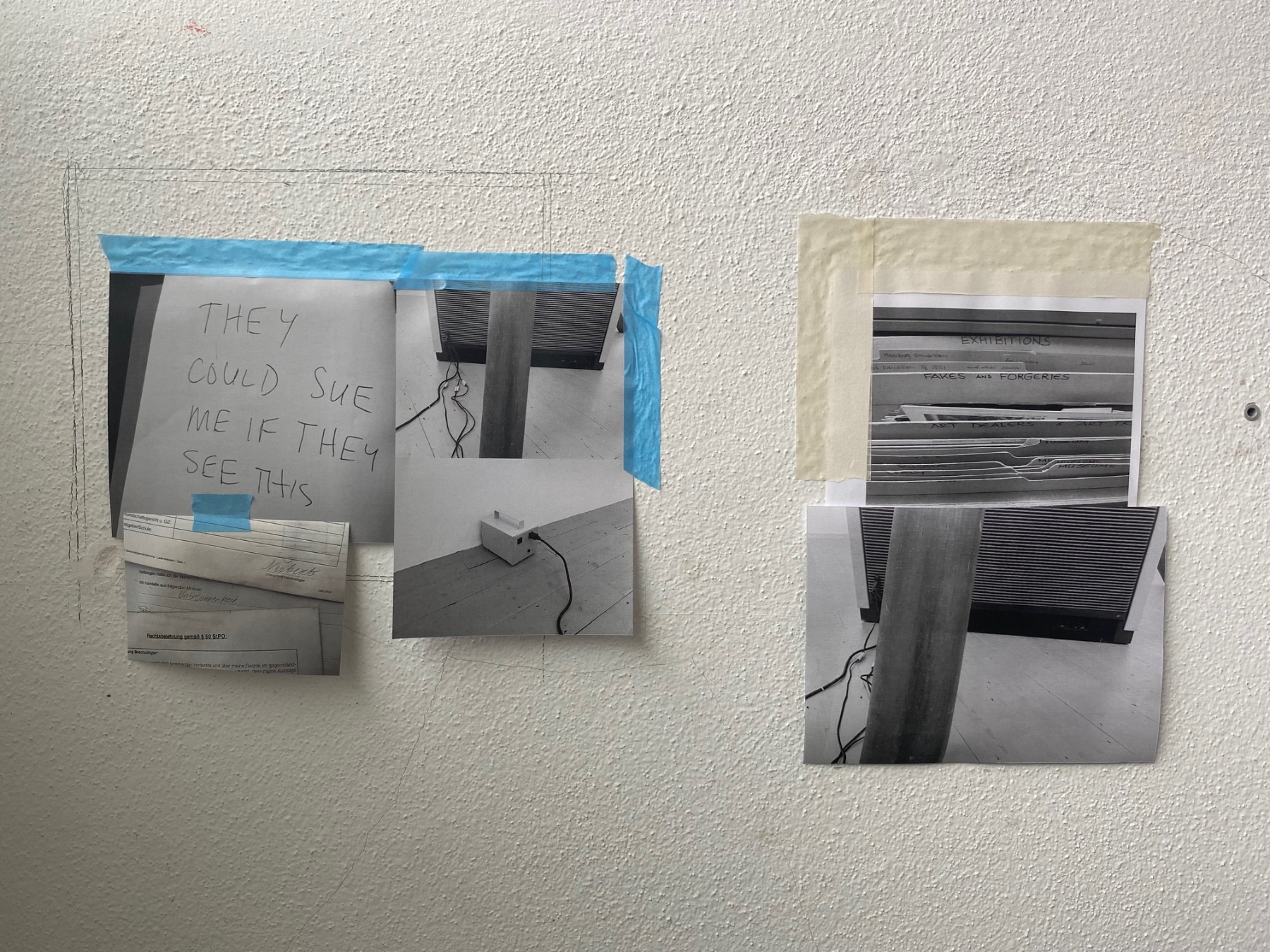

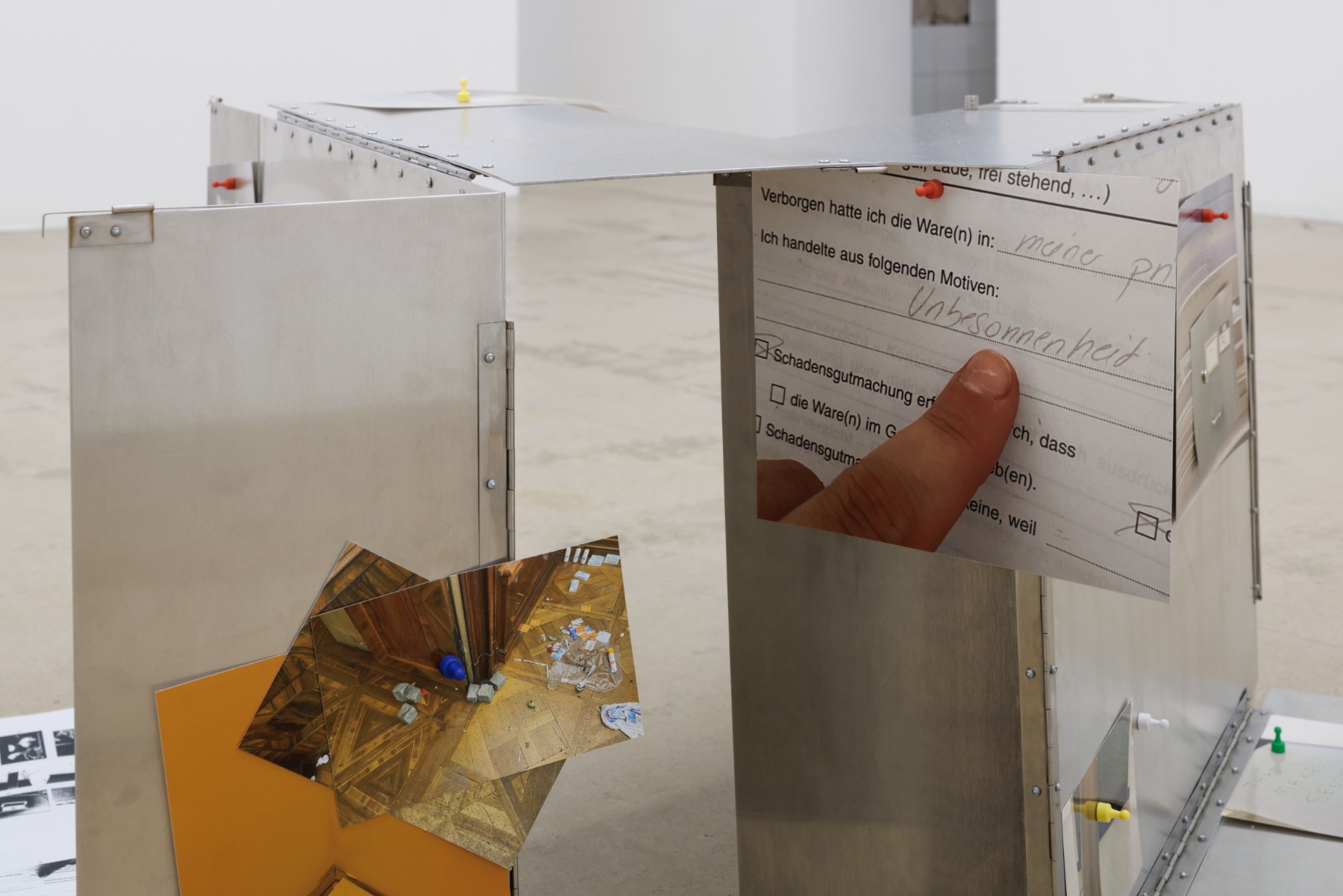

The second group of your works included in the exhibition is a metal structure/installation that resembles windows, boxes, even medical equipment. On the smooth and anonymous surfaces of these metal sculptures, you have pinned, inserted into seams, or even hidden from view various visual layers – photographs. These materials mark your interest in appropriation and quoting by borrowing and referring to very specific artists, both living and dead. We see Mike Kelley, Jason Dodge, and Lutz Bacher – names that are internationally known and, at the same time, shrouded in mystery. In the context of the exhibition, it makes me think of a kind of ‘analog thinking’ or ‘overlap’ in which you draw together and build relationships between those who, at first, seem to have nothing in common – for instance, Pauls Kundziņš and Mike Kelley.

L.N.: All of these artists are very important to me. In my practice, I have turned to studying them in depth precisely because of their mystery and relevance; I am interested in the position of the artist-as-rogue. I refer to the zine of the exhibition, which includes a nice quote by Nicolas Bourriaud on artists’ intuitive relationship with art history now going beyond what we understand as appropriation and inferring an ideology of ownership. In recent decades, everything is, to quote Bourriaud, ‘moving towards a culture of use of forms, a culture of constant activity of signs based on a collective ideal: sharing.’ Absolutely everyone who makes art is trying to represent the experience of life in some authentic way. There is a constant sense of common purpose that remains unchanged. Along with copyright and ‘theft’, I am very interested in dialogue, legacy, and playing with what we regard as canon.

Sand from the Riežupe sandbanks and the drying process in Inga Melder's father's garage in Snēpele. The sand was used in the sand installation "Symbiocene". Photo: Juris Melderis

In closing, I would like to talk about the collaborative sand installation Simbiocēna (Symbiocene), made in collaboration with artists Elīna Vītola and Ieva Putniņa, which, spread out on the floor of the final room of the exhibition, serves as a tangible continuation of the pigment laboratory located here in the ‘kitchen area’ of the exhibition. Inga, could you expand on your work with colour pigments, its origins, and your interest in them?

I.M.: Thinking back on why I was interested in this process, I have to draw parallels with why I consciously chose to study restoration. I was influenced by where I grew up – Kuldīga – a town that was and is resilient, charming, and a bit shabby, but so very much connected to history. My hometown has also influenced other conscious choices – fine art painting and being active in pedagogy, which in the practice of painting, is reflected in my interest in layers and narrative. In the context of the exhibition, this is perfectly visualised in a sand painting – an installation where, in dialogue with Elīna and Ieva, we used pigments as a painting tool on the less familiar ‘canvas’ of sand.

In the foreground: Sand installation "Symbiocene" by Inga Meldere, Elīna Vītola and Ieva Putniņa. Photo: Ansis Starks

I studied painting in Helsinki and took a course on materials in which I learned that making pigments from plants was a new way to talk about the different agencies of nature, and even more simply, a way in which to equip myself with materials for painting. Not in terms of painting something with plants, but to extract dyes from them which I could then use for other things.

Scenes of the pigment boiling and drying process. Photo: Inga Meldere

Although painting with these pigment paints doesn’t interest me in the traditional sense, they fascinate me as a material. To look at the plants around me, to find out what else they can tell me beyond their smell, appearance, or whether they are medicinal or toxic. To admire plants for their ability to form a network of roots that keep the sand stabilised on a windy day. Rooting and networking also serve as a model for the cooperation we used while creating our ‘Symbiocene’, and which is why we chose this term as the title of the installation – borrowing and sharing with each other not only the energy of doing things together, but also the joy of creation.

Inga Meldere&Luīze Nežberte selfie / Riga, 2024

***

Exhibition Sunpoles was on view at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre from September 21 till November 1, 2024

***

[1] Latviešu Vispārējo dziesmu svētku būvju evolūcija 1873–2023

[2] Pauls Kundziņš (1888–1983), architect, historian, and founder of the The Ethnographic Open-Air Museum of Latvia

[3] Latvijas Architektūra