The in-between as art

A conversation with Paula Zvane / shortlisted for the Purvītis Prize 2025

Paula Zvane’s work combines experimental searches for materials, intermediate states between the familiar and the unfamiliar, and a constant desire to challenge the boundaries of sculpture. She works with a wide range of materials – metal, animal furs, sugar, plant fibres, and even tea mushrooms – creating creations that do not belong to any particular species but that are made from a fusion of familiar elements. Her artistic exploration moves beyond the conventional aesthetic, striving for an uncommon beauty that reveals itself through the process of material transformation and the fallacies of perception.

Her exhibition Neredzams (Invisible), shown at LOOK! Gallery in February 2024 and nominated for the Purvītis Prize, is an experience of a whole – a ‘dream-room’ in which the viewer is drawn into a surreal environment where objects seem both alluring and frightening at the same time. Technically, the making of the work itself is an in-between state – a process in which the outcome is never entirely predictable.

In the following interview, Zvane talks about her creative process – how she goes from an idea to a finished work, why exploring the properties and durability of materials is so important to her, and how perceptual play through materials becomes part of her artistic language. She also shares her thoughts on both the international and the Latvian art scenes, on working in laboratories and collaborating with scientists, and how an artist can become ‘invisible’ by immersing themselves in their work.

Work in progress

You currently live in London. A city of layers, contrasts and constant change. What is it about this particular cityscape that most captures your attention right now? What visual or emotional feelings does this city evoke in you at the moment?

Yes, I live in London, and one of the things I’m most drawn to here is the really vibrant art scene – the exhibitions, the creative processes, and also the way people perceive art. London is one of the central points of art development in the world right now, which makes it a very competitive environment. It’s the reason I’m here, and it’s the place where I challenge myself the most in what I can do in art. London inspires and challenges me, both professionally and personally.

Heavy Sleep, 2023. Oil on canvas, 105x85 cm. Photo: Gints Zvanis

You have studied in Latvia, London and Iceland. How have these different experiences influenced your view on art and the use of materials? Has each place left a lasting impression?

Absolutely. Studying and living outside of Latvia has strengthened me and made me realise that there is no one right way to make art. I went abroad to study in order to develop technical skills that I didn’t feel I could do to a sufficient level in Latvia at the time. So it was a natural and necessary step to take. It was particularly significant for me to work with several materials at the same time.

It was important for me to develop my metalworking skills and to broaden my view of sculpture. When I was studying at Central Saint Martins arts and design college, I had the opportunity to work alongside fashion design students who, for example, were welding corsets. This inspired me and made me realise how closely different creative disciplines can be linked. From that, new connections and collaborations grew.

In Iceland and London, you have worked in the synergy between art and science – for example, in the Making Waves residency with Japanese scientists. How have these collaborations influenced your artistic thinking? Is science and experimentation with materials as important to you as the means of expression in sculpture and painting?

It is important for me to be able to realise my ideas as precisely as possible, and this often means working with a wide variety of materials. I tend to follow the idea, which often leads to complex materials and technical solutions. That is why experimenting with materials is as important to me as traditional means of artistic expression.

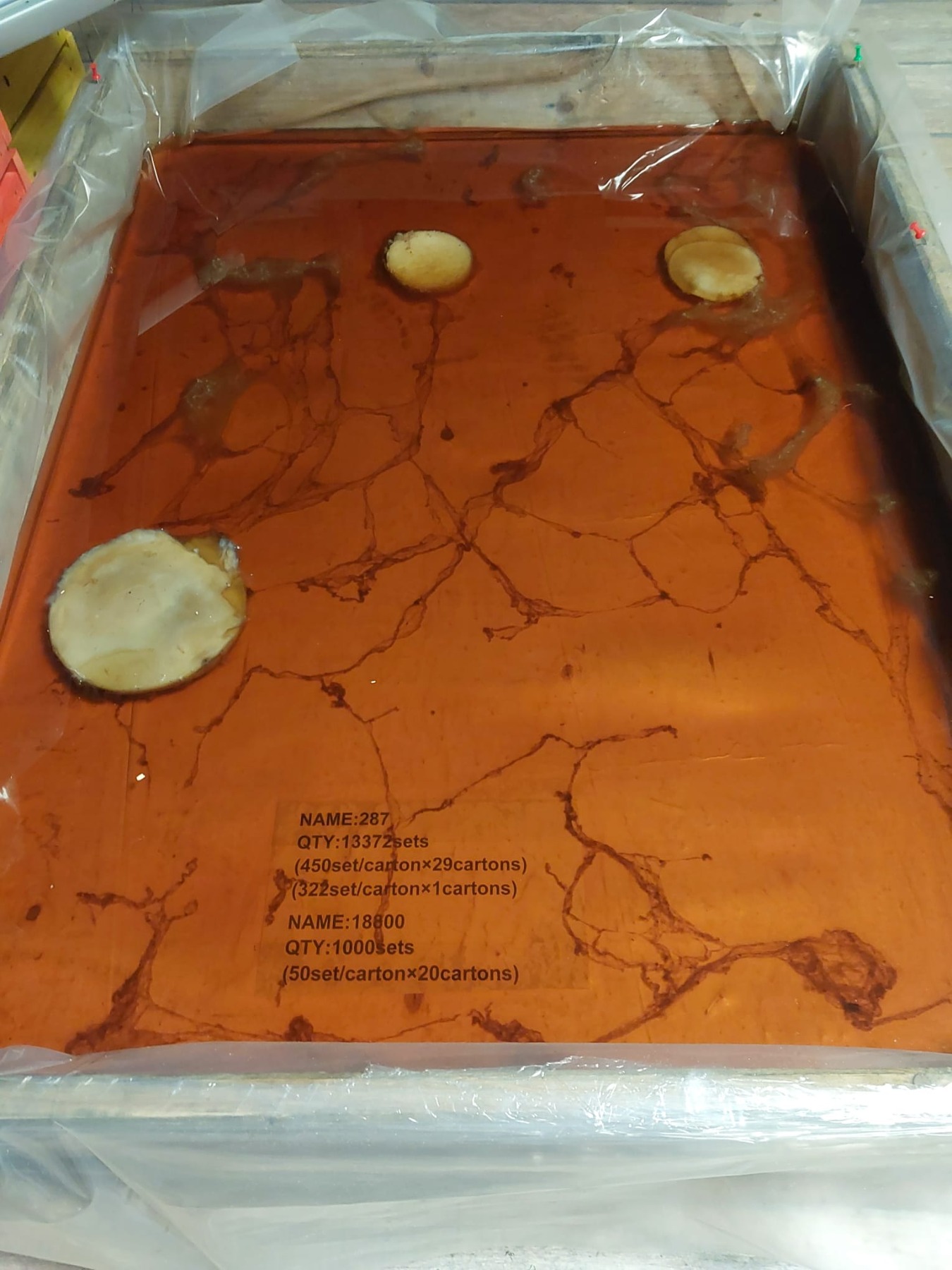

While studying in London, I had the opportunity to participate in a residency where I worked with Japanese scientists in laboratories, exploring biological innovation in art. During this residency, we experimented with slime mould and tea mushroom cultures, creating new structures and shapes. The project was also based on observations of nature and how such observations can help in the process of creating a work of art. This experience was special. But I do love the traditional art mediums. With anything that seems experimental, I always go back to classical painting and sculpture.

Invisible. Exhibition view. Photo: Emīls Lacums

Would you say that your choice of materials is based on a careful research process during which different combinations and reactions are tested, that is, without any room for intuitive exploration?

Materials follow the ideas; I don’t think it’s an intuitive process...perhaps more logical. The choice of materials is always based on research and experimentation until I fully understand the potential and possibilities of each material. It is important for me to understand how a material will behave in the long term, what its properties and possible applications are. When experimenting, I look not only for visual impact, but also for durability and quality.

Mole with Sugar Claws, 2024. Fur, metal, sugar, 105x88x33 cm. Photo: Emīls Lacums

Does the technical work with materials also require collaboration with other craftsmen or artisans, or do you execute the whole process by yourself?

I do most of the work myself, but it also depends on the budget. If resources are limited, I work alone because it’s important for me to learn and understand the process. But whenever possible, I am happy to work with professionals – especially if specific knowledge is needed.

If, in the future, the opportunity arose to do larger works on a larger scale, I would definitely involve other professionals. There are many talented engineers and scientists who are interested in the arts and willing to take on the challenge of creating something seemingly impossible.

Turning to the Purvītis Prize-nominated exhibition Invisible, it would be interesting to know how, for example, the ‘mole with sugar claws’ was made. Are the materials in this work treated with any specific technologies that produce this surreal effect?

For a long time now I have been working on a series of sculptures in which I create creatures that are not specific animals but in which you can recognise parts of different animals. I’m interested in the idea of how various materials and shapes can be combined to create something unprecedented. For example, this piece is shaped like a mole, but the tail is visually similar to that of a chicken. All these creatures have been transmorphed – they don’t belong to any particular species. It’s important for me to create objects that seem at once familiar and alien, suggestive and slightly disturbing. This mole wants to be petted, but at the same time, it seems a little scary.

Technically, this piece is part of a series in which I weld metal skeletons and place skins on top of them. I’m interested in how different surfaces can translate different emotions – this piece is a good example of that. The choice of materials and the treatment allows for an illusionary sense of reality where the viewer can feel both the tactility and the visual disparity between the familiar and the unexpected.

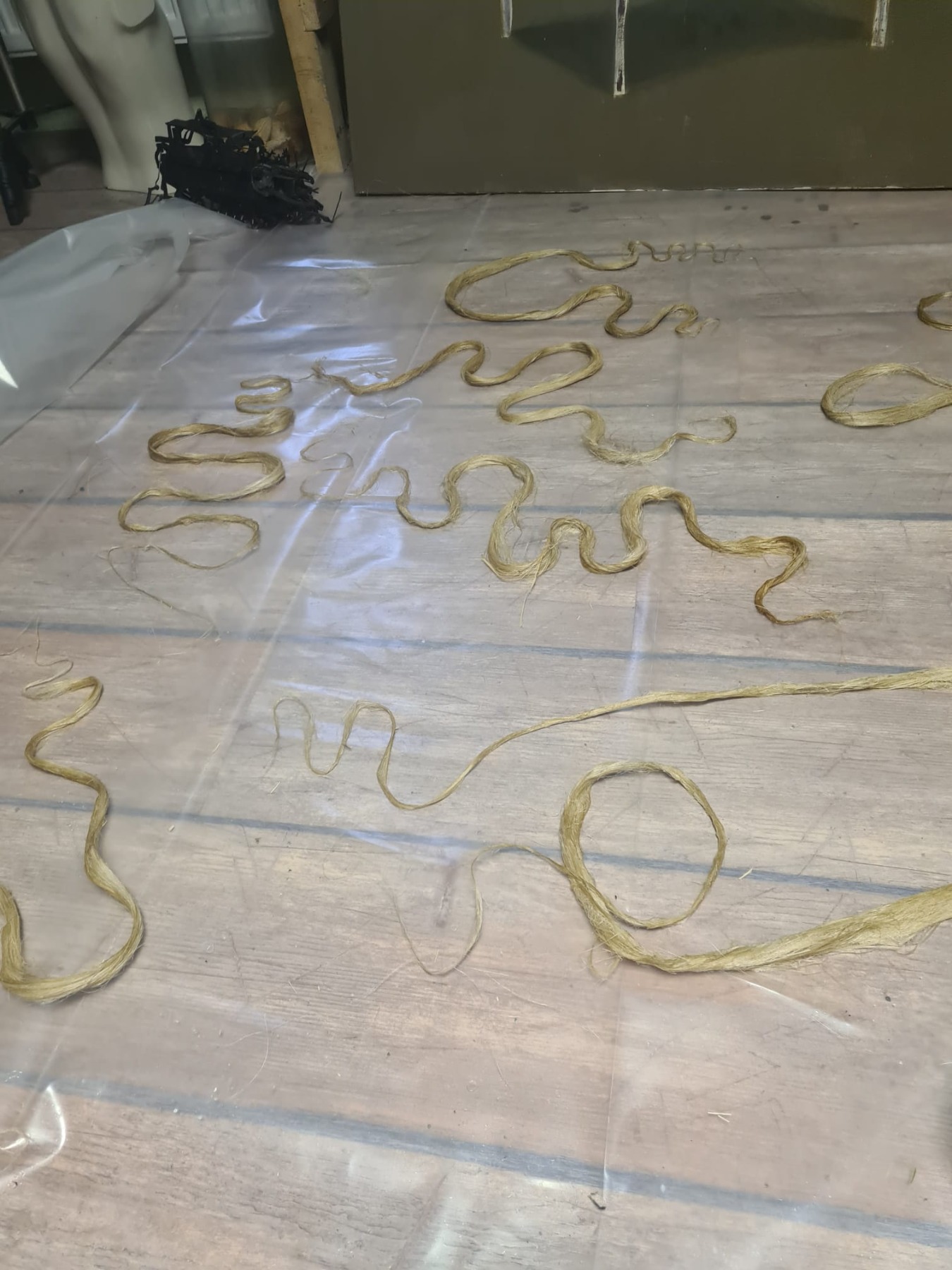

Work in progress

How would you describe your creative process in general, step by step?

I write a lot – I think that ideas start in word form and only then turn into images and forms. First, I write down everything that comes to mind, then I try to visualise and draw these ideas, and only then do I come up with the best material solution to realise them.

Some ideas become three-dimensional objects, others become drawings or paintings. A lot of inspiration comes from observation – when looking around, I pay attention to clothes, fabrics, architecture. I think about materials, their meaning, and their possibilities – what would happen if the material itself started to think? How could I connect with it? What happens when two different substances are fused together? What is this new third substance that emerges from them?

Through my studies I have acquired a wide range of technical skills that allow me to experiment and build sculptures, to test ideas and follow their development. For example, when welding steel skeletons, I am fascinated by the idea that they are stronger and more durable than those made of bone – they are like special ‘fish-bones’ or ‘internal fences’ that give new narratives to the material structure.

Work in progress

Velvet, hair, sugar, leather – these are all materials with a strong tactile dimension. To what extent is the viewer allowed to feel these works physically? Does touch play a special role in your art?

The works in the exhibition are not meant to be tactile, although I am very interested in this aspect. In this exhibition, they have to be ‘touched’ with the eyes. I am attracted to the way different materials can mislead the viewer’s perception – for example, by creating the illusion that something that visually resembles skin is actually made of plant fibres or a tea mushroom. The exhibition is a kind of delusion and a dream, and dreams are delusive.

In the future, I’m interested in thinking about the tactile sensation and how that can be achieved visually. But there is a challenge here – anything that is exposed to direct touch wears out quickly. Think of bronze sculptures, for example... And I think that’s very beautiful!

Work in progress

But these materials will change over time even without being touched. For example, leather can dry up, sugar can crumble...

By the way, the tea mushroom can be very durable if handled properly. If it simply dries out, it becomes brittle and turns to dust, but if treated with wax and other methods, it can last for years. The works in the exhibition have been preserved for seven years. There are designers who make bags and jackets out of this material. Of course, the material changes colour over time, but that is part of its natural transformation.

Katrīna Jaunupe, the director of the Art Needs Space foundation, commented that your work is both fragile and very robust. Do you agree with this statement? How do you achieve this contrast?

Yes, I totally agree. I don’t specifically try to achieve that contrast, but it comes naturally – maybe because I’m interested in the properties of materials and their potential. My work is powerful and sensitive at the same time – that’s how I see it. In terms of robustness, I want to be even more sustainable in the future. I’m interested in how, for example, the winding and fragile fibres of flax could be made hard, strong, and seemingly everlasting.

Is there a material with which you don’t have a relationship? Which material has been the most challenging? And are there any that you haven’t yet managed to tame?

I think I’m a very bad ceramicist/potter! I have a difficult relationship with ceramics – I can never get it to look exactly the way I want it to. Clay, on the other hand, I really like, but I use it more as a patch during the creative process than in the end result. But, in general, I like a challenge, and if a material seems difficult, I just want to work with it even more.

Invisible. Exhibition view. Photo: Emīls Lacums

The title of the exhibition, Invisible, seemingly addresses a conceptual challenge. Does the viewer have to actively search for this ‘invisible thing’ in your work?

The exhibition is visually present, but it is called Invisible. I am interested in this tension between perception and reality. I’m interested in the way the viewer looks at the exhibition.

My aim is that when someone is viewing the exhibition, they do not ‘see’ anyone else who may be viewing it at the same time – the viewer is invisible, and I am also invisible. The exhibition is made up of my remains.

The exhibition was made during winter, when everything was dark and shut down. I spent a lot of time in my studio – I didn’t go anywhere, I didn’t meet up with anyone. I was physically absent. It made me think about the feelings of presence and absence...and also about how an artist can become ‘invisible’ by immersing themselves in their work.

The works appear, yet the physical presence of the artist is no longer there – they are in a sort of dream world. They are in this conditional state of ‘invisibility’.

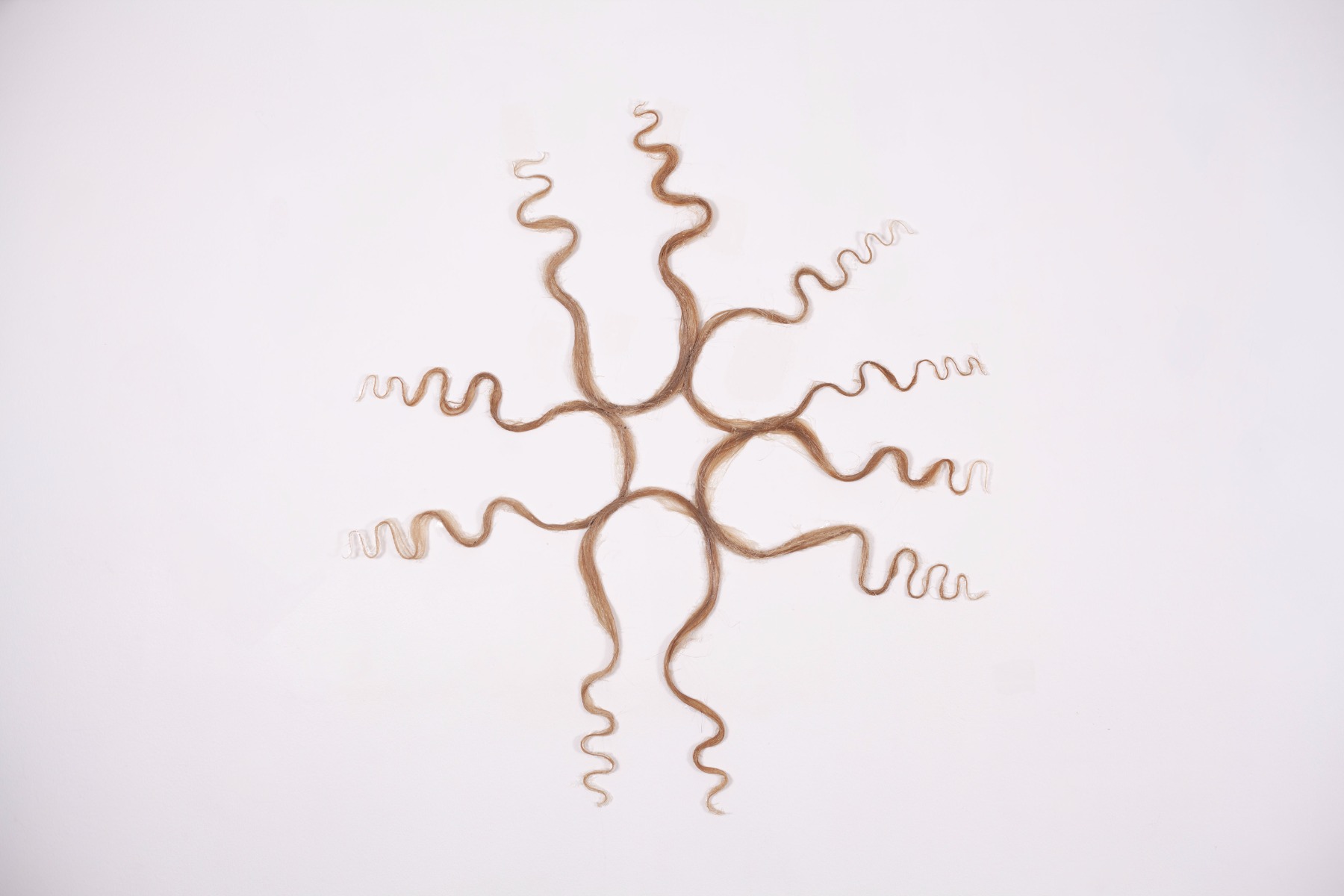

Hair Stars 1, 2024. Linen, epoxy resin, 101x92 cm. Photo: Gints Zvanis

Do you think the artist should be ‘visible’ in their work?

The artist is always present in their work – even if that is not their intention. The longer I work, the more I see that inevitably, my vision and experience infiltrate each work. It’s like the law of conservation of energy – everything I put into my work stays there in some form. Over time, movements and traits that are characteristic of me establish themselves, and inescapably, they permeate my work. I think it’s called the artist’s ‘signature’ – the combination of all these things.

You mentioned that the exhibition is like a dream. Is Invisible like a dream that can’t exist if you disassemble its structure? Can the artworks in this exhibition stand on their own, or are they like elements of a larger interconnected system?

This exhibition is designed as a whole – all the works were created specifically for this environment, and together they form a single spatial experience. Of course, some of them could stand on their own, but in this context, they are part of a single dream-space where each element complements and interacts with the others.

In terms of my approach to working in series, it’s more about working within the confines of a certain material while experimenting with different technical solutions. In this exhibition, these parallel approaches come together to create a closed, dreamlike environment – that’s because the specific space of the LOOK! Gallery evoked in me associations with a ‘dream-room’.

Heel Tent, 2024. Tea mushroom, textile, 40x40x16,5 cm

Hairs hearts, 2024. Linen, epoxy resin, 48x7 cm

Photo: Gints Zvanis

The following couplet appears in the exhibition statement for Invisible:

As if. You would be stuck.

In your mind. Your hair creating shapes of stars.

To paraphrase, is a ‘mind stuck in hair in the shapes of stars’ a metaphor for the creative process?

Yes, absolutely. And I think it can also be seen as a metaphor for the process of observation. This phrase, I think, is a verbal-visual reference to what can be seen in the exhibition – a kind of suggestion to the viewer that they just might truly see what is there.

You address in-between states – between sleep and wakefulness, between the material and sensation, between the familiar and the unfamiliar. Do these intermediate states seem more fruitful to you than clear boundaries?

In-between states are an important theme that I work with. My works often exist in this in-between state, too – for example, they are not specific animals, but they consist of familiar details that can make the viewer think of various possible characters.

The in-between state is something very seductive, something that is pleasant to be in – a state when one’s reality is perhaps not as comfortable as one would like. The in-between state is a dream that is between sleep and wakefulness.

Working with materials and being in this experimental territory is also an in-between state, because you never know exactly how it will turn out. The in-between state, I believe, is a very beautiful theme.

Work in progress

Do these characters – or creatures, as you call them – have a particular literary, mythological or visual source of inspiration?

Yes, I think all these images are combined from different sources of inspiration. I couldn’t name one particular myth or book that influenced them, but there are certainly many parallels with fairy tales and myths.

I have always been fascinated by the idea of creatures that do not fit into one category – creatures that are partly familiar but, at the same time, completely alien. It’s along the lines of Dr. Frankenstein – combining different things and creating something new. Visually, I have always been attracted to the principle of medieval bestiaries, in which animals were depicted not according to their actual nature but based on interpretations, assumptions, and various cultural layers.

But I don’t want to mention anything in particular – in my work, I try to create a new perspective on these creatures so that they are not just references to the past, but also a way to think anew about form, essence and boundaries.

What’s your view on the development of contemporary art in Latvia today? Do you think the local art scene is open enough to experimentation and new artistic approaches?

Art should not adapt to society’s readiness. It doesn’t matter whether the environment is ready or not – the artist’s task is to offer new forms, the shocking, and the seemingly boring, thereby pushing the boundaries of perception. Often society itself does not know what it wants, and that is why the artist must show their vision and guide cultural development.

The artist must not let society define what art is and what an artist should be – that is the artist’s job: to be, to create, and to challenge. Latvia’s cultural environment needs even more diversity and new ideas!

Latvia’s contemporary art scene is evolving, but in order for artists to have more opportunities to express themselves, an adequate infrastructure is essential. I think it is very important for young artists to have access to studios where they can learn the basics of working with materials. Such knowledge would not only help them to better understand technical processes, but also to know how to plan and realise their work effectively.

I also believe that contemporary art education should be included in primary and secondary school curricula. Art is not only aesthetic expression, but also a reflection of the times – it records thoughts, social changes, and cultural development. However, I am not sure to what extent society is aware of this and appreciates this.

It is very important to maintain artistic freedom – expression should never be restricted or censored. Every work of art has its place and context in which it best speaks to the viewer and fulfils its purpose.

Latvian artists should strive for international cooperation – establish contacts with foreign institutions and artists, involve them in projects both here and abroad. Latvia has many talented and knowledgeable artists, but our geographical location is not a traditional route for collectors and art market participants in Central Europe. It is therefore particularly important to actively engage in the international circuit and make Latvian art more visible.

One of Latvia’s greatest needs is a museum of contemporary art. It would be a strong reference point for both artists and audiences, helping the public to better understand and appreciate contemporary art. At the moment, it seems that many people perceive galleries as something alien, but a museum could become a bridge between art and society, promoting interest and understanding of contemporary art processes.

Of course, economic support is also an important aspect – Latvia should have more people who buy art, as this would contribute to both the development of art and the sustainability of artists. But artists themselves also need to be entrepreneurial and look for ways to finance and develop their creative activity. This is one of the most difficult challenges in the creative profession.

In Latvia, it is particularly important to allow experimentation and new initiatives to take place. Art should be a platform that stimulates thought and debate; it should challenge the conventional. Only through active engagement and continuous development can contemporary art reach its full potential.

Paula Zvane. Photo: Arnis Balčus

How would you define your place in the Latvian art scene? Do you still feel connected to the Latvian art process when working in an international environment?

Yes, I am very actively involved in the Latvian art scene – through exhibitions and especially through the organisation of residencies and participation in the Savvaļa open-air art space. This autumn we are planning an exhibition together with Icelandic artists, which will take place both in Estonia and Latvia. Alongside that, we are creating a joint residency at Savvaļa, to which we are inviting artists from Europe and the Nordic countries.

Of course, exhibitions abroad and the experience they bring are also important to me. Each place offers its own specificities – both challenges and advantages. The making of art never happens in ideal conditions, and no place offers a utopian environment where everything runs smoothly. It is important for artists to adapt, to collaborate, and to be able to deal with difficult situations. It’s not that everything is ‘better’ abroad – it’s just different, with different challenges and opportunities.

If I had complete freedom of choice, I wouldn’t want to be tied to one particular art environment – I would just make new work anywhere I had the opportunity to do so. What would be even better is if I could collaborate with inspiring people all over the world. At the same time, I love developing projects in Latvia because many foreign artists have a special experience when they’re here. They appreciate the freedom of expression that Latvia has to offer, which is not always available elsewhere.