All of my objects are practically spaceships

A conversation with Romāns Korovins / shortlisted for the Purvītis Prize 2025

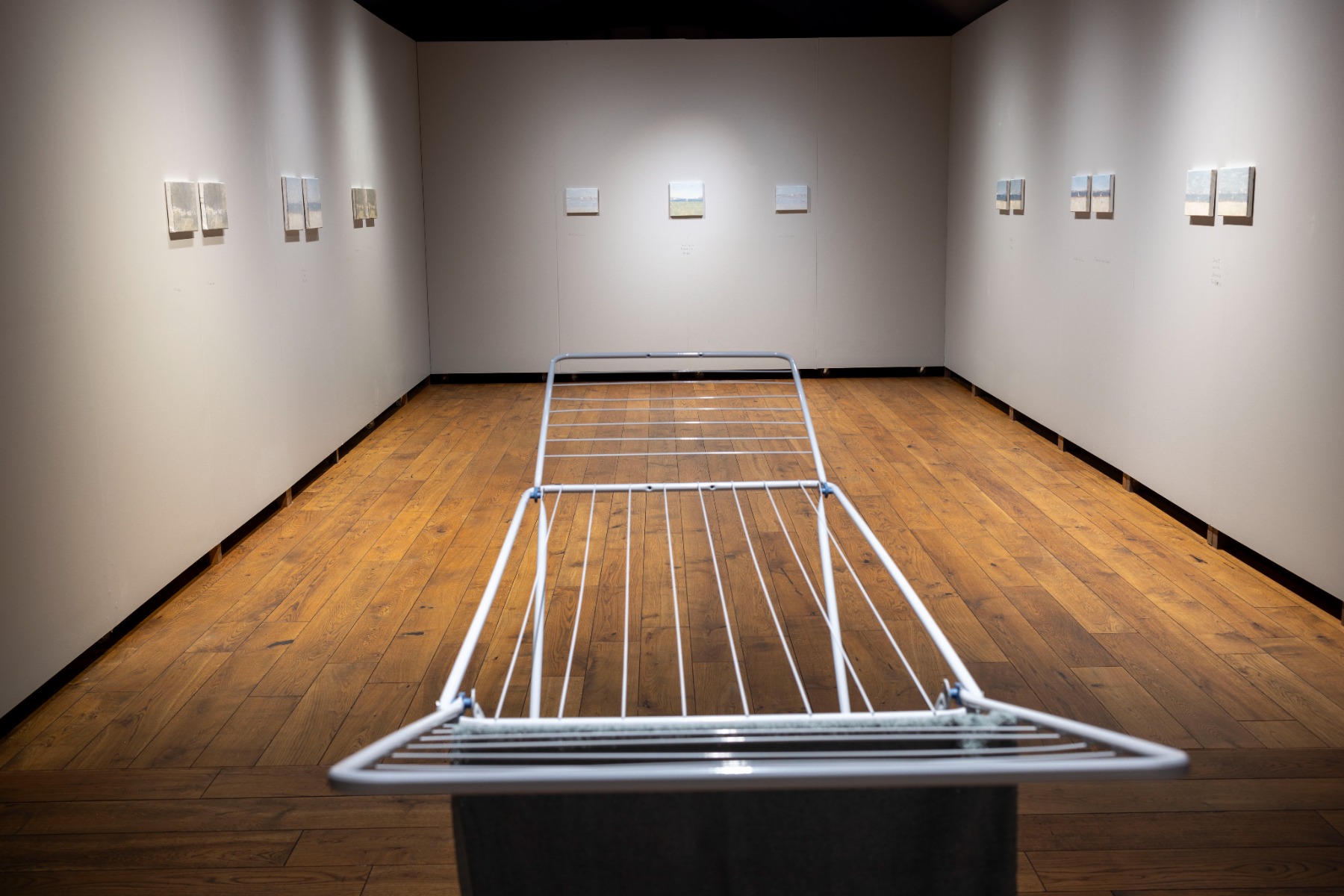

Last spring saw Romāns Korovins’ solo exhibition ‘Let’s Die Together’ run at the Rothko Museum in Daugavpils between 1 March and 19 May 2024. Nominated as a finalist by the Purvītis Prize panel of experts, it will go on view once more, this time as part of the Purvītis Prize finalists’ show at the Latvian National Museum of Art from April 12 through June 8, 2025.

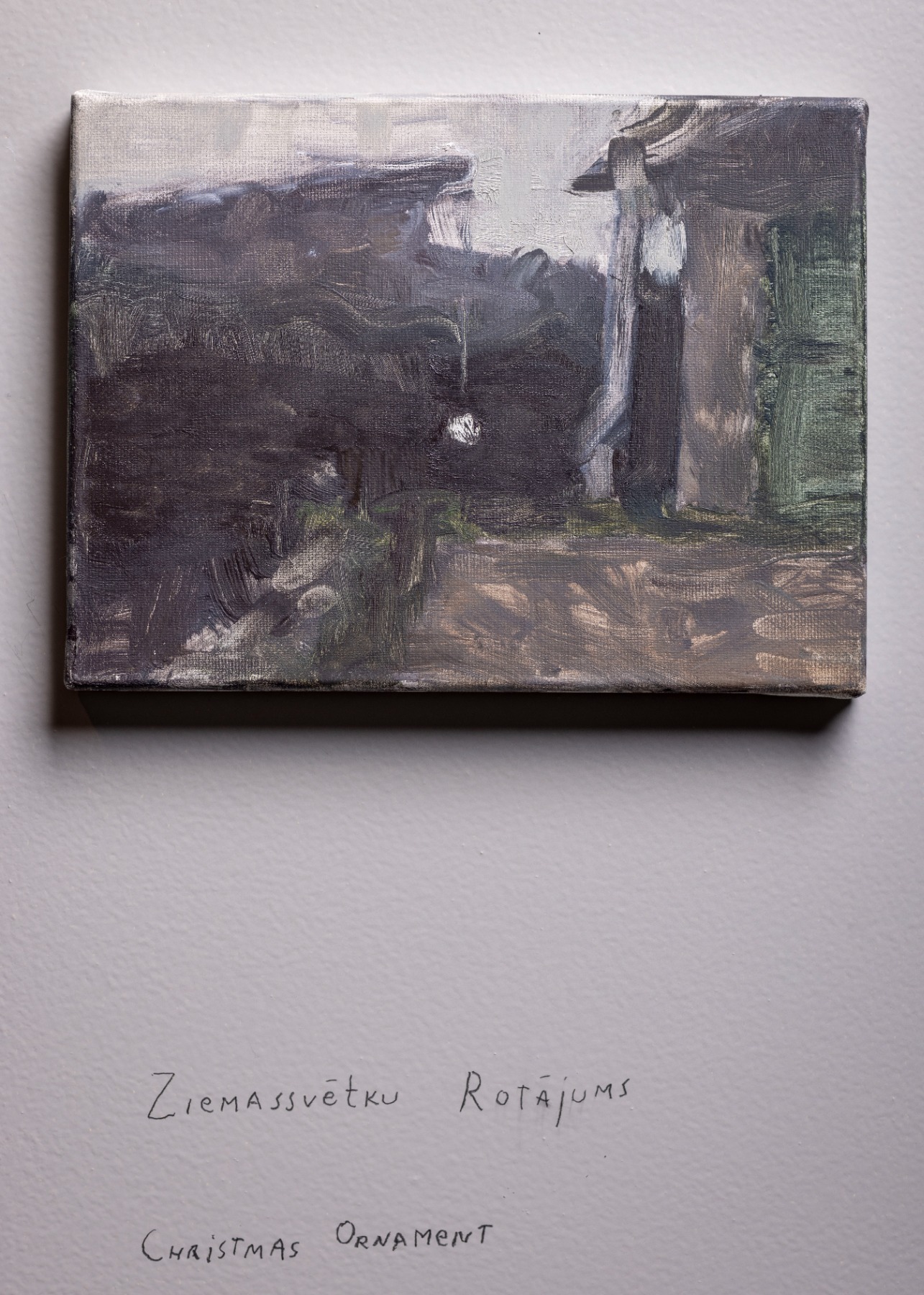

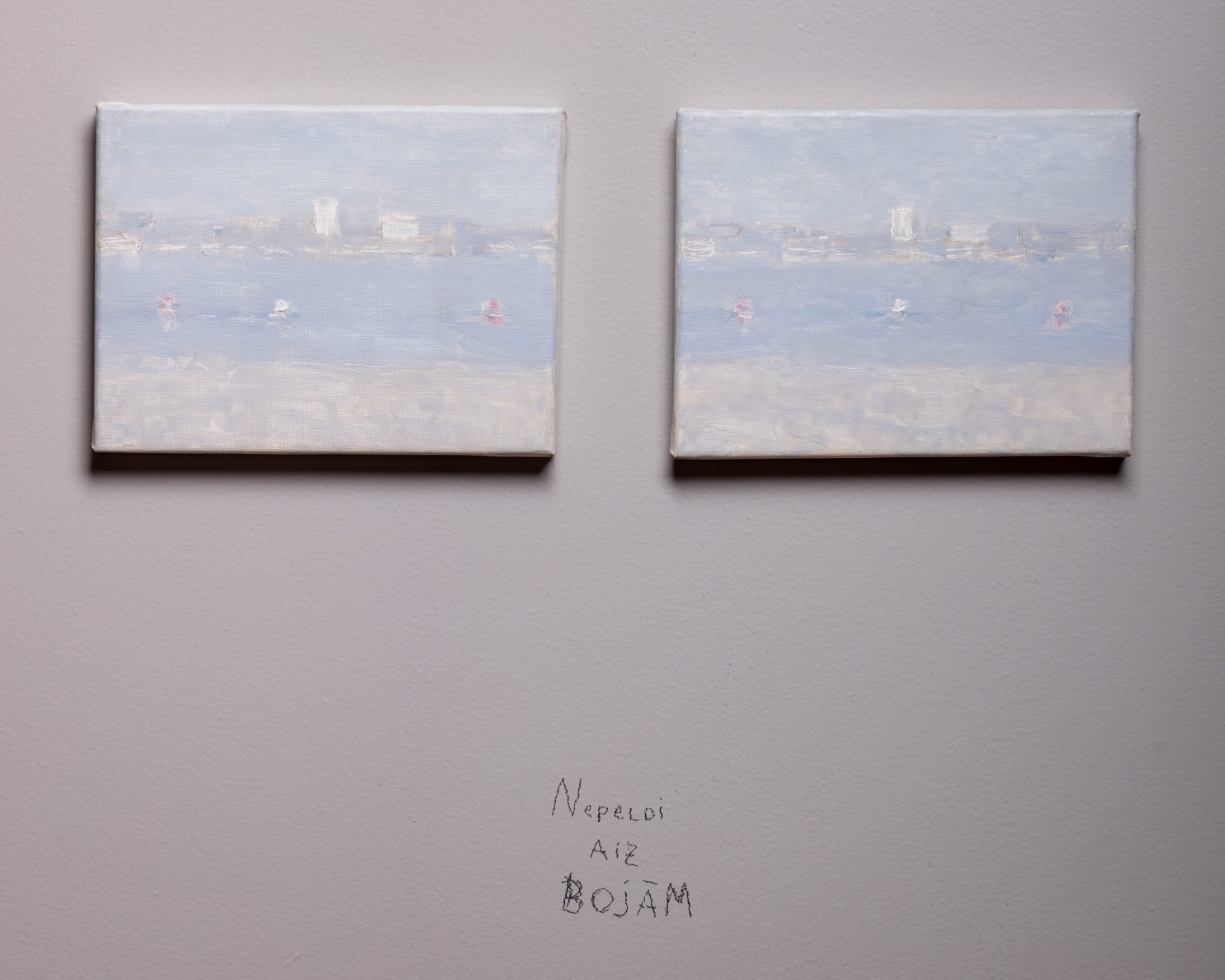

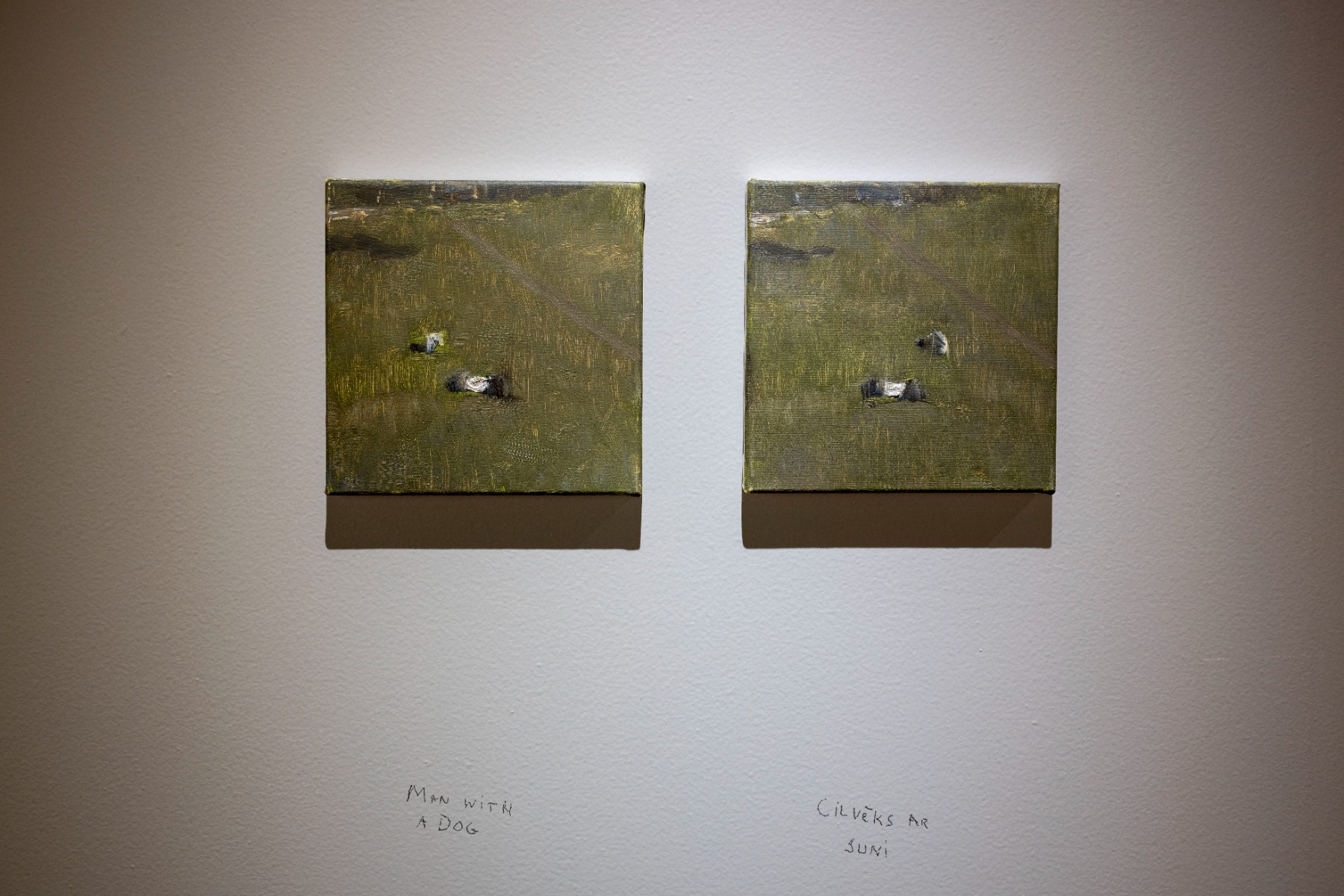

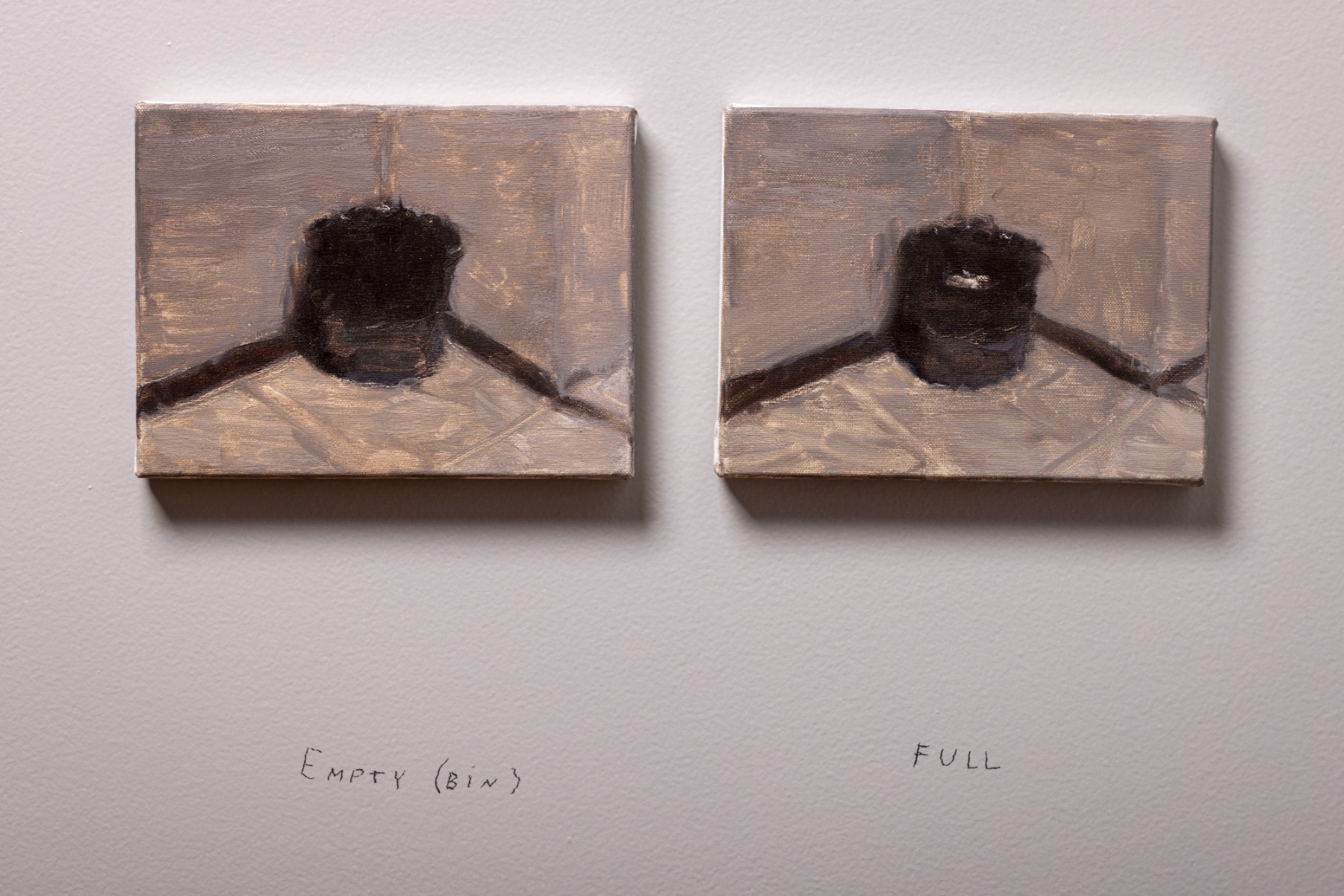

‘The art tools in Romāns Korovins’ arsenal are a paintbrush and oils. Dots and lines. Brushstrokes. His paintings are quite simple: an element of a varied degree of realism or abstraction is placed in the centre of the canvas, while the rest of the composition has been decluttered of anything superfluous. A diptych. Two paintings denoting the starting point and the end of an event. But what exactly has happened in between? [..] Staying true to his characteristic approach, the artist centres his ‘Let’s Die Together’ exhibition around the subject of life – time – and relationships. A couple. A family. Two people who have spent a lifetime together. Sharing the joys of celebrations and the swamp of mundane worries. Working, hoping, feeling happy and disappointed. It seems like they have been living hand in hand, as one – but have they? People may be going through the same thing yet experience it differently, responding to it each with their own unique feelings and emotions. Even should they die together, drawing the line beyond which neither holds the advantage of revising the shared past, the two versions of said shared past can be mutually incommensurable: overlapping in places yet miles apart in others’ – this is how the idea behind the ‘Let’s Die Together’ exhibition is described by its curator Iliana Veinberga.

Photo: Didzis Grodzs / Rotko Museum

‘What makes art important? A pause, an emptiness filled with a content that you cannot really define using words,’ Romāns Korovins told me in 2019 when I interviewed him on the occasion of becoming a first-time Purvītis Prize nominee for his exhibition entitled ‘Satori of Master Wu and Master Lee’. His transition from the kind of ironic trick photography he had been making for quite a while (including publishing his hallmark photobook ‘Rock’) to painting, quite similar in its mundane stories and markedly understated style, was already very much underway at the time. In fact, it could be as well described as a comeback of sorts: Romāns initially was trained as a painter at the Department of Graphic Art of the Latvian Academy of Arts and started his artistic career as a painter but switched his media in the 1990s, turning to video and settling in the director’s chair for a long time: making commercials, music videos and shorts, which eventually led him to photography, which was – once again – within spitting distance from painting. All this experience amassed by having his fingers in so many different visual media pies, so to speak, has now brought a new quality to Korovins’ painting, a new level of saturation – despite the minimalist colour scheme and narrative. It is genuinely a case of ‘there is nothing and everything there’, to rephrase the title of our said previous conversation that took place at the Orbita office in Ģertrūdes Street.

This time around, we spoke under completely different circumstances, remotely, via Google Docs. I wrote down a question and messaged Romāns to let him know in WhatsApp, and he answered whenever he had the opportunity. The comments you will find in the text, like ‘laughs’ or ‘smiles’, were included in Romāns’ answers. Sometimes the pause between two paragraphs could last for several days. The conversation faded out and then resumed again. In all, the whole thing took us three weeks. You could say it was born from pauses. A pause, an interval, the white noise between streams of information – these are all key notions in Romāns’ practice.

Your exhibition was hosted by the Rothko Museum. Is Mark Rothko a key figure for you? Did you see his works ‘live’, as it were, when you were living in America?

Mark Rothko is very much ‘my’ painter. I love his cosmic emptiness. I think his whole art is very logical: it is an evolution from his early works to the final paintings where anything superfluous is swept away and what remains is the otherworldly existence of the colour. His last works are all about the purity of death, not about the worldly stuff. And yet his early figurative compositions are also very much about painting, about the colour. Thank goodness we have a place where we can see that in Latvia as well, his foreign-era cosmic classical pieces. The Rothko in Daugavpils is an excellent museum, a very competent one; it has its own character, its own face. But did I see Rothko’s work while in America… I don’t even remember; all the things I saw in the United States have merged together into one whole; it seems to me now that I did see a Rothko show, as well as De Kooning and Pollock: that’s how much they have become a part of me; they are practically family to me.

Your exhibition fits your trademark colour scheme – greyish-green, brown with unexpected flashes of pale blue – quite well. Even the objects that are included in the exhibition – the chair, table, laundry drying rack with a couple of towels – do not disturb it. To what extent are your colour solutions informed by the reality that surrounds you?

I tell you what, if you see all of a sudden something pink or orange in my stuff, call me. (Laughs.) This is true that my colours are exactly the ones we see every day. LV-type of colours. Brown, grey, bluish tones, muddy green, typical baroque. 500 years before the Impressionists, folks painted brown and black shades. Using cool tones. You cannot get away from it. It is in our blood. This unreal baroque light: there is nothing better than that to take you to the mystical. And since I paint the things that are around me, the objects also part of my life. In this case, all the objects from my studio travelled to the exhibition together so that no-one was left behind feeling rejected. (Laughs.) The paintings, chairs, tables, bottles, speakers, even the Bob Dylan records I listen to when I work.

This reminds me of a conversation I had with a Latvian poet whose aunt, after listening to her reading her poems, called her a ‘poet of the mundane’. Can we say that you are an artist of the mundane? While you do, of course, paint nature as well, it is always somehow very human-used. Quite mundane, everyday-like as well. And it is very obvious that it is exactly through this mundaneness, this ordinariness that you can enter some kind of completely different levels. Like going up in a lift.

The word ‘mundane’ seems to carry a kind of negative connotation. As in, I’ve had it up to here with this mundane shit. It is something very down-to-earth, completely devoid of fantasy. Whereas all of my objects are practically spaceships. (Laughs.) I am an artist of the cosmic-mundane.

Wherever I find myself, that is where I paint whatever I see around. In the garden, I paint the garden. On a bridge, I paint the river. In the studio, I paint the window. All the objects that are around us are equally valuable for me. It is all about light and shade. Patches of colour. Subtle contrasts. Everybody must know these objects well. It makes it easier for the viewer to enter this state of light metaphysics. And the title also contributes to this gentle entrance into the painting.

The original title of your show at the Rothko Museum, now represented in the Purvītis Prize final, consists of two words: ‘Nomirsim kopā’ (‘Let’s Die Together’). The accompanying text to the exhibition makes it clear that the subject you are exploring is relationships, a couple who are so close that they may dream of passing away together. And yet even their shared past is perceived by these two in two different ways. Why was it important for you and why did you give the exhibition this title?

I liked the idea of two people who lived together and died together. They went through the same situations, yet each of them experienced them slightly differently. It is this ‘slightly’ that actually constitutes the content of the show.

The subject of a pair, a couple, is the subject of a diptych, which I have been pursuing for quite a long time now. It is the perfect match: a pair of pictures and a pair of people. What could be better than that? And the point after which you can take a look at a life in its complete form. I mean death.

I borrowed the actual title from a song that has the lyrics: ‘Let’s come together. Right now. Oh, yeah. In sweet harmony.’ That is how the ‘Let’s Die Together’ came about. It sounds horrible in Russian: ‘Umryom vmeste’. And equally horrible in Latvian, too. (Laughs) I should have called it ‘Baby, Let’s Die Together’.

Pair, couple, coupledom – it is a significant principle for you in general. You have many diptychs capturing a ‘before’ and an ‘after’, complete with a certain assumed interval between the two. How and why did you arrive at this approach, extensively represented at you exhibition in Daugavpils?

Every time I happened to see two similar objects, I experienced a kind of aesthetic ‘torque’, a kind of visitation. Angels came on wings to visit me. There is a kind of koan to be found in looking for a difference between two similar objects. There is something Zen-like about it. A presence/absence or the other way round – it’s all about absence/presence, and there is a great difference. (Laughs.) A diptych for me is the shortest story ever. The beginning and the end. The pause between these two works – this pause is the actual content of the story, the zero state. Zero state between thoughts: yeees, how very Zen. (Laughs.)

What could reveal this zero state to us? The fragility of life, the ephemerality of it? What lies beyond the zero?

What lies beyond the zero is the thorny path to enlightenment. To quote a song by AC/DS: ‘It's a Long Way to the Top If You Wanna Rock-n-roll…’ (Smiles.)

Could you tell a little about working on these pieces? Did you paint everything at your studio? From memory, from photographs? Or did you paint some of it ‘from nature’?

Usually, when I see something noteworthy, I make like a little study on my phone. This is what I work with later. I remove the superfluous details, add whatever is lacking. I paint alla prima, all in a single take. Two pieces simultaneously, a diptych. It takes about five hours. And I never go back to them. I am all for this lightness and freshness of sketching. I cannot stop working until I am done. Until I have finished my work, it is impossible to do anything else. And going back to a painting for a second time, it is like attempting to step in the same river twice.

You may ask – if the picture is so unique, why don’t you show it all by itself? There are more of them at exhibitions and they are part of some sort of sequence. There are different ways of showing paintings in the exhibition format. You can show just one picture or edit them together like film frames. Editing – what follows what… the order – means emergence of new storylines. The individual frames combine to create a composition, something quite similar to a poem or a song. The content here is very poetic yet not literary. These are visual poems.

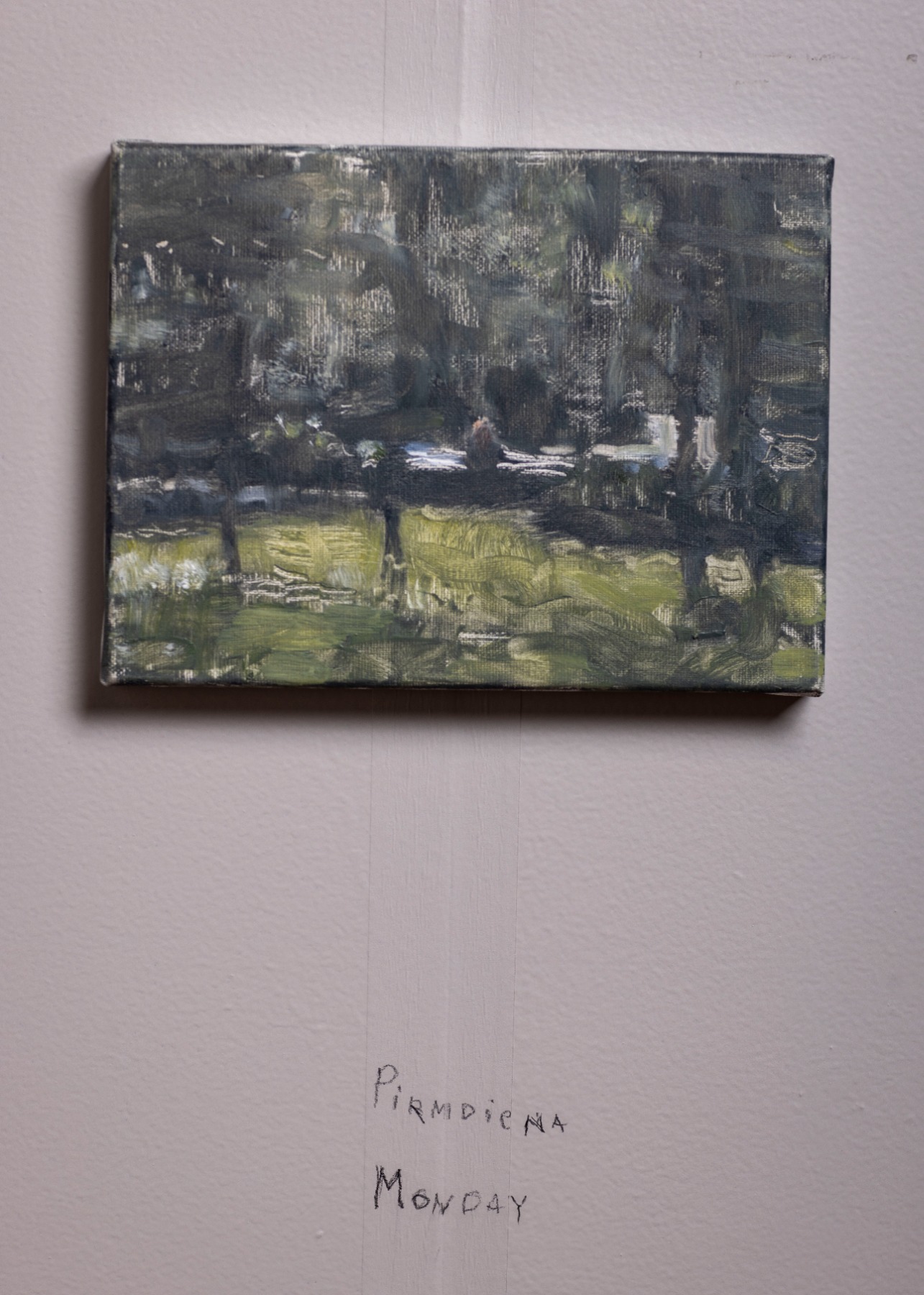

And yet words also matter to you, right? For you, the titles of the paintings become a part of the visual concept; these are handwritten inscriptions directly on the walls of the exhibition space. Just a tiny bit unsteady, very life-like.

Yes! I do it so as to not mess with the viewer’s head. If I speak about a boot in my work, if that’s what matters and that’s what is the most important thing, then the piece is called ‘Boot’, not ‘Reflections on the Colour Yellow’. This kind of title allows the viewer to immerse in the picture, to grasp the subject. I paint a wheelbarrow and a drying rack, so I want the viewer to see the relationship between the wheelbarrow and the drying rack in the painting. That is why I painted the picture in the first place.

There is another type of title, a witty interpretation of the story. For instance, old tyres, half-buried in the ground in a field – that’s one image; if you write the title ‘Used Rainbows’ next to the picture, it transforms into something completely different.

As for writing the titles on the wall – they are usually hung on the wall in the shape of little plaques… which creates a separate element. I mean, the painting is an element and the label, the plaque is another one. I have always found it quite distracting. You could write the title directly on the painting but letters and words are very active by nature. They hog the spotlight. By which I mean that the contrast between the letters and the image somehow become the main thing. That is why I write the title with a pencil right next to the painting, to tie together the picture and the space of the wall. It is almost as if it was floating in the air and making a sound. This creates an impression of lightness. The word merges with the image.

The unity of everything is important to you, then – a situation where all the elements, including the environment of the particular space, narrate a story they all share?

Each element, from a power socket to a photo fallen on the ground, is equally important. An exhibition is also a work in its own right, a single composition, one whole where individual paintings are its components. Therefore, the more character there is to the room, the easier and more interesting it is to come up with a story for an exhibition. In other words, I see a room, I think about it and find the right content for it.

The exhibition will now move to the National Museum of Art. A completely different space with different proportions. Is it going to be the same show? Or perhaps we should call it a representation, an impression of the original exhibition for the requirements of a different museum?

That’s right, it will be a different exhibition now. You can record a nine-minute song but you will have to make a 3:50 version for playing on the radio. A bit like that. It still is the same song, though – a love song. (Laughs)

Of all the other museums in the world, where would you like to show your works if you could choose any of them?

Oh, you know what, our own museum is quite enough for me: it has so many beautiful galleries. These days I somehow find myself wanting things that are achievable. In the words of a character from the animation film ‘Around the World in 80 Days’, use what you have in front of you and don’t go searching for anything else.