When the blue light suddenly comes on

A conversation with Indriķis Ģelzis / shortlisted for the Purvītis Prize 2025

Artist Indriķis Ģelzis is one of the candidates for the 2025 PURVITIS PRIZE. His solo exhibition Ūdeņaina dienas actiņa (Watery Day’s Eye) was on view at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre in 2023. His exhibition Watery Day’s Eye will be on view again – as part of the2025 PURVĪTIS PRIZE finalists’ show at the Latvian National Museum of Art from April 12 through June 8, 2025.

‘Mediated through our society living under the precondition of shattering flux that permeates the politics of relationships, identities and economics, Watery Day’s Eye is an ode to the personalised, analogue cyberspace masquerading itself under the foil of visual resemblances and contextual meaning of the public swimming pool. A folkloric, nature-inspired colour palette casts the customary white walls of institutional normality with brightness. Flashes of experience and memory act as binders for sculptural appropriations of the infographic ecosystem in metal. Urban planning and the ebb and flow of the stock market are represented in the gallery via welded, bended, oiled artworks which absorb and entrap the shapes and forms of the living organisms and bodily details. The functionally utilitarian details – tiles, carpets – of the living or communal spaces lying underneath establish the rhythm-grid to which the emotional passage of the entire Watery Day’s Eye exhibition plays out,’ wrote Zane Onckule, curator of the exhibition, in 2023.

‘And then I realised that all I could offer was a more cutting view of the world. I’m learning to be open to illogical choices and to be committed to them. I’ve noticed that viewers who don’t fully understand the nature of a work of art tend to entrust themselves to it, and I find that deeply moving...and it also creates a huge sense of responsibility,’ Ģelzis said to me at one point during our conversation in his studio, a large room with high ceilings in a former industrial building on Vagonu iela. ‘As an artist, I work with a visual language that, truthfully, exists in a world where there is no sound and no words.’

The language is distinctly modern and, at the same time, based on various art movements of the 20th century, from Constructivism to Brutalism. Using this language masterfully, Ģelzis creates his own series of sculptures from steel, wood and fabric, reflecting a syntactically fractured reality that is open to wide interpretation. These works are initially created in a digital environment, and only later take on their analogue form.

Indriķis Ģelzis holds a master’s degree from the Visual Communication Department of the Art Academy of Latvia, and later continued his studies at the Higher Institute of Fine Arts (HISK) in Ghent. Since 2012, he has held 26 solo exhibitions and participated in numerous group exhibitions worldwide. Yet Watery Day’s Eye is his most significant and impressive artistic gesture to date. How did that come about? He started talking about it as soon as we sat down at the table and I turned on the recorder: ‘...I recently looked at the photographs of the exhibition, and realised that it is probably even more relevant than it was two years ago.’

Why is that?

In a way, the exhibition is about change. And looking at everything that’s happening in the world... Are we starting [the interview]?

Yes!

Good. Speaking of change, in 2015, while studying at HISK, I consciously put an end to doing video art and decided that I wanted to find a single and distinctive form of expression that I would continue to cultivate until the sun stopped rotating around my axis. And luckily, that is what happened. Now that ten years have passed, I have found that the visual language I created has, over time, split into three sub-directions. Watery Day’s Eye is an exhibition in which all of these strands came together. One of the challenges for this exhibition was to create the conditions that would further define the hierarchy of the works’ mutual existence. It was a serious challenge. I didn’t want the artworks to become too theatrical in their own way. I remember that during the making of the exhibition, I felt that they were in too close of a dialogue with each other, but it was important to me that each of the works retained its autonomy and existed on its own and made a direct connection with the viewer.

Images from Indriķis Ģelzis’ solo exhibition "Watery Day’s Eye" at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre / August 25–October 8, 2023. Photo: Mārtiņš Cīrulis

Theatrical...?

Yes, I don’t know if ‘theatrical’ is the best word for what I want to say. During my studies at HISK, I came into close contact with an American professor, John Welchman, who recommended I study Michael Freud’s essay Art and Objecthood. In it, he criticises artworks that focus only on formal visual dialogues between objects because they lose emotional connection with the viewer. He stresses that art should be a direct experience, not a passive observation of an object where works only communicate with one another. Of course, I won’t say that this opinion is either right or wrong – Michael’s ideas are still relevant – but they may seem outdated in the context of contemporary art.

Do you mean that each work should have more space around it?

This includes the space around all of the artworks. I had originally envisioned this exhibition in one large exhibition hall, but I had to fragment this idea across the KIM? Contemporary Art Centre’s four exhibition spaces, which I think turned out very well. I have to admit that after a break of ten years, I was seriously determined to create a new video work and include it in this exhibition. I had imagined it as a link between all the works in the exhibition. I tried different ways of approaching it, but couldn’t find a meaningful solution. There was a complete void in my head until I realised that I could deconstruct the medium of video into its defining variables of image, movement and sound, and then from these components, create a mechanised and immersive installation in the space. I was immediately intrigued by this idea, and I knew very clearly what to do next. It was comforting to know that the six years I had spent studying video art had not been thrown away, and that over time, this knowledge had led me to an exciting solution. I remember the first time we managed to successfully run the installation, especially the moment when the lights in the room switched from fluorescent to blue and the sound came on. There was no other option but to gasp.

What does this blue light, which occasionally turns on, mean to you?

‘Fragments’ of blue light simulate falling into a lagoon. In this case, it was interesting for me to imagine a digital and electric water array in which the whole field of consciousness is immersed. It was important to find a way to create a sense of the presence of a great and unfathomable force, to which both the viewer and all the works in the exhibition are subjected. I quickly realised that symbolically, the Baltic Sea was an interesting source of inspiration, as I grew up in the presence of this massive body of water and it has always been a constant influence on my identity. And, of course, the current geopolitical reality, which is becoming increasingly oppressive. But, you know, this installation is very multifaceted – I see it as a kind of mechanism of consciousness, like in a public space or information landscape that is so saturated with information that it becomes impossible to digest. That’s why I made this installation with one-way communication that goes only towards the viewer: it gives the viewer various facts and, at the end, asks a question that is impossible to answer because the space is automated – there is no live person there who can listen to the answer.

I think you’re right. You live in an environment that you are used to, that is safe and understandable, and suddenly the world takes unexpected and rapid turns that are beyond your control. And now you’re looking at it all with different eyes, like when the blue light surprises you.

Yes, and I could say that I now live with that pair of eyes, but I also feel how quickly my eyes have adapted to new circumstances. Actually, when I was working on this show, I was going through a big change. My wife, Sabine, was pregnant and we were expecting our daughter, Bianka. I started working on the show in the first few months of the pregnancy, and when we opened the show, Bianka was only a few months old. I think that was our most intense period so far – we had just two weeks of parental leave, after which we both went back to our studios. Emotions were running at their highest, I think! [Laughs]. Now, two years later, we’ve become used to our parental roles and have established a good daily routine.

But now we are on the threshold of a much more serious change in the world order, and that makes me look at this exhibition in a completely different way. Looking back on it, I have the feeling that it exists in a kind of frozen state, one in which you can’t really tell if there is a big event coming up, or if something has already happened. But what am I waiting for?

There are two phases in the exhibition: the first is when the fluorescent lights are on, and the kinetic sculptures are synchronously ticking. And then there’s the moment of switching – the fluorescent light changes to blue, and the ‘daisies’ stop – and so does time. At that moment, you’re receiving new information.

It is interesting that we understand it this way. I think in more peaceful times, people would have probably talked about ‘satori’, the divine light that comes from above and gives insight… ‘And suddenly, everything was clear!’

Two years have passed, and I have the feeling that the world has changed beyond recognition. Consequently, this exhibition will be looked upon very differently.

You mentioned new information... In general, the visual language that you have developed over these ten years is, I think, strongly influenced by infographics. It’s ‘information through sculpture’.

You know, during my studies in Belgium I rediscovered myself as an artist. Before that, I was mostly looking towards Western culture. I had my heroes that I liked and tried to interpret in some way. However, I felt that I was imitating someone; I had a huge identity problem. During my studies, I realised that I had to invent my own visual expression that only I could create, based on my life experiences and what I had experienced in the world. Or, for example, I should trust the visuals that were present in my life growing up as a Latvian, here in Riga. When I was looking for the strongest visual antecedents, I thought of my dad and grandfather’s construction drawings of buildings, as well as Gustavs Klucis’ works, which I remember vividly from museum exhibitions in Riga. Looking back now, I understand why, as a young boy, Klucis’ works appealed to me at the time – they seemed visually familiar, similar to the technical drafts of my father and grandfather. Eventually I came upon statistical distribution curves, and they appealed to me because of their universal parameters – graphical statistics analyse information from the whole of humanity without focusing on any single individual or group. And then I realised that the visual language of infographics is very similar to architectural sketches. I made my first digital models, and then the sculptural works started to incrementally take on shape.

How did you choose the material?

Once I had made the first digital sketches, I started going to home improvement / construction stores to look for materials. I remember when I first walked into one that specialised in metal – I touched some plain steel and my hands were instantly dirty. I immediately associated it with pencil graphite and thought, ok, this could be a bit like a three-dimensional drawing. I also found it interesting that metal is used in the construction of urban infrastructure, which I personally associate with the skeleton of a city. When metal becomes the body of art, for me, it symbolises the skeleton of a meaning, a point, an event, or a situation.

I had come to the decision that I would use metal, but at the same time, I realised that I was missing an essential element that would activate the constructed object and make it come alive. I remember sitting in our apartment in Antwerp, among piles of fabrics while Sabine was sewing together pattern pieces, and literally being swallowed up by the realisation that I was sitting in the answer I was looking for [laughs]. I was fascinated by the idea of the material collision between metal and fabric, which together form a kind of relationship between something animate and inanimate. Eventually, I came up with the idea of using pieces of fabric to highlight headless figures. Symbolically, I imagine that the headless figure is incapable of making decisions – it has no thoughts, character or soul of its own, which points to automated or programmed action...like the digital assistants that are becoming ever more present in our daily lives and are supposedly making our lives easier.

Yes, automation is advancing rapidly.

Much faster than we are. It would be great if I had a robot that could weld for me.

But for now, you do it yourself. What’s your process?

There is something architecture-like in my working process. First, I always work out the digital model down to the last detail, and when that’s ready, I print it out on a white A4 sheet and write down the dimensions of the lines with a pen; then I start welding it together. Over these ten years, my skills in making digital models have become more refined and sophisticated, largely due to the improvement of my finger reflexes and the accumulation of intuitive knowledge. In some ways, I can see parallels with the abstract expressionists. I find it fascinating –you take a big brush, saturate it with paint, and make seemingly chaotic movements on a canvas; and you do this for years, until the works take on an inexplicable logic. I think it’s a way of revealing personal characteristics through repetitive and instinctive gestures, and getting at something very intimate. In my case, gestures and reflexes are expressed by sliding my fingertips along a touchscreen and organising the lines between two and three dimensions.

And then what?

I take metal square tubing and rods, an angle grinder, a tape measure and other tools, and start welding the pieces together, one by one. My work is always set on the floor, and I’m literally standing in the middle of it. Only when the work is completely welded do I pick it up, step back, and look at how it’s turned out. When the structure is ready, I draw the outlines of the wooden pieces that I will need on cardboard, which I then hand over to be made by a carpenter. A painter’s palette has paints in various colours and tones, whereas my ‘palette’ consists of wood veneer and fabrics in various shades and textures, which I use to control the expression of the artwork. I must confess that working with colours and textures often gives me a huge headache, because there are an infinite number of combinations and solutions, and there is always the feeling that one will be better than another. So I always feel that I am making the wrong decision.

You started with figures – automated beings – and then you moved on to anatomical systems and structures.

If I’m not mistaken, it was 2021 when I accidentally opened an anatomy encyclopaedia that my mother had given me. As I was going through it, studying the anatomical structures of the neck, spine, throat, eye socket and ear, I vividly remember imagining them as living spaces. I was very interested in that. It was an important moment that helped me start a new creative period. By imagining what would happen if, for example, the floor of the room interacted with the spinal structure and worked together, I was able to come up with new structural solutions. In fact, in my latest work I see a slight tendency towards surrealism. For example, in the piece called Naktsliesma (Night Flame), I depict the interaction between the fire and the cartilaginous structures of the neck, and to symbolise the presence of a flame, I painted the structure orange. This work, in my opinion, offers several interesting interpretations. We express words through our throats, but everything that goes up in flames – disappears. If we look at the human body symbolically, when it is confronted with emotional or psychological problems related to communication, expression or internal conflicts, then the throat is the place in the body where these problems manifest themselves, and it can result in feeling a burning pain in the throat.

You also exhibited some works from your series Time Camouflage. Those are completely different.

In 2020 I started making small, quick works – study cases, you could say. My aim was to learn and look for different compositional solutions that could later be integrated into works for walls. I didn’t take them too seriously at first, until a couple of friends noticed them and found them interesting. I see these works as clock mechanisms or places where different elements interact, such as landscapes, throats, caves, rain, teeth, hand gestures, (eye) pupils, and so on. In preparation for Arco Madrid, I have developed a new series of works. When I was making them, I was thinking about teeth that could be played as piano keys. This is my most direct comment on the contemporary zeitgeist in which words have become either very sensitive, or surprisingly frightening.

Your exhibition also featured spoken text.

Note that the entire structure of the exhibition was divided into five sections, each corresponding to the elements of nature: earth, water, air, fire and the universe. For each of these sectors, I created a separate paragraph inspired by the aesthetics and structure of television shows. I vividly remember a television quiz show where the facts were given first, and the question was asked at the end. The facts I presented in this show were related to the changes that take place through concrete materials and phenomena, followed by a rhetorical question. I wrote the text myself and tried to denote different states, for example, in the ‘water’ sector, I wrote: ‘A drop of water changes into a snowflake, changes into a feather, changes into an unidentifiable bird, changes into an urban drone, changes into a fan, changes into a boat propeller, changes into a daisy, changes into a clock. Which eye are you falling out of?’

How is your visual language perceived by audiences outside of Latvia?

The reactions are pretty similar everywhere, I think. At some point, I noticed that people first see my work as ‘pure’ abstraction, but when they catch on that there are figures in there, they go back and start all over again and try to decode the works. As I mentioned before, I quite deliberately work on making my visual language universal.

How do you choose the titles for your works and exhibitions?

The name Watery Day’s Eye came easily. If I have to wrack my brain for a long time about the title of a work, I feel that I am facing an internal and unnecessary conflict. With Watery Day’s Eye, my aim was to describe a state of disorientation but without emphasising whether the disorientation was due to positive or negative reasons. The eye can also become confused and momentarily lose its orientation, whether through tears of joy or tears of sadness.

Have you ever created a digital model that doesn’t transfer to being built in real life? You look at it and realise – this just doesn’t work...

Yes, I’ve had works that just annoyed me a lot. I tend to eventually destroy such works. Sabine doesn’t let me, but I sometimes do it without her knowledge.

Do you just take them apart?

I pick up an angle grinder and it’s gone in 15 minutes. Then I sweep it up into a small pile.

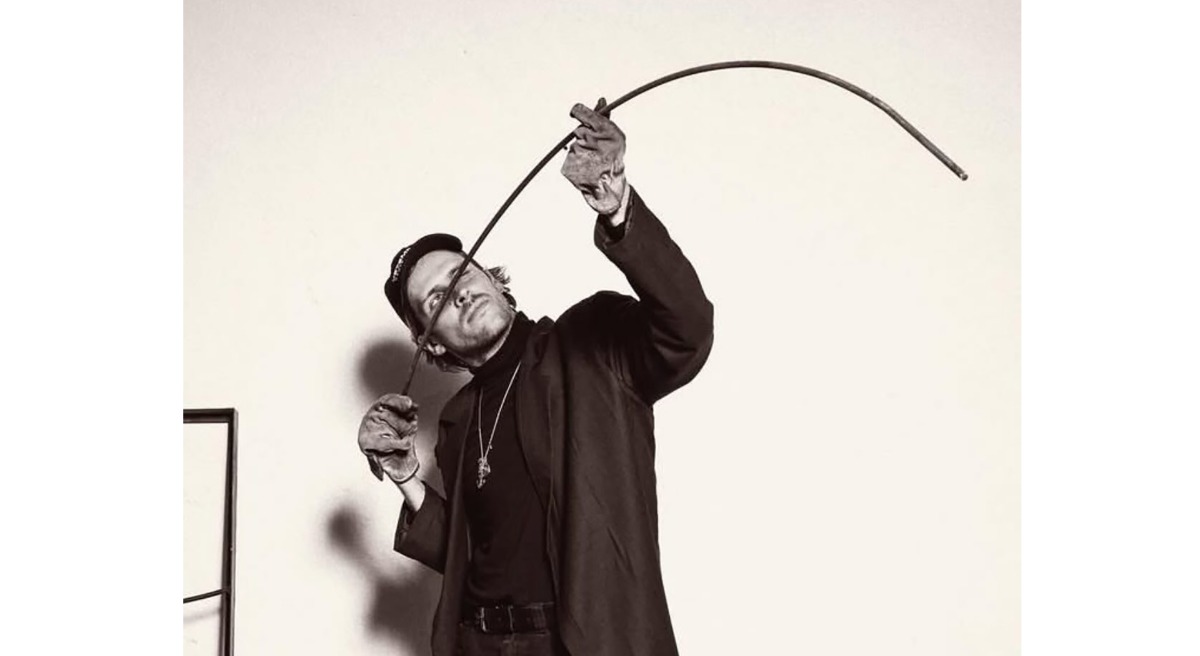

Indriķis Ģelzis a the opening of the exhibition. Photo: Kristīne Madjare

I think that everyone who knows anything about Latvian contemporary art is familiar with your artistic style and visual language, which has been the result of a big change. How do you see the future? Are there any more big changes waiting for you, or is this ‘art language’ good enough for you to develop it further and deeper?

I have identified with this style of art, and giving it up would be quite difficult and existentialistic. I must admit that for a long time now, I haven’t been working just for fun or inspiration – I have a mission. So, when I feel exhausted and like there’s nowhere left to go, it’s actually my very being that is exhausted. It’s not a struggle with artistic expression but a struggle with my deepest motivations. How much do I want to transcend these difficulties? It would be easier to just try something else... but it’s like being a singer who can’t just simply change his voice.

I don’t want to generalise – I can only speak for myself – but if I were to look for a new form of expression, or even just add new material, to me, this would be a sign of weakness and surrender. On my palette I have metal, wood and fabric – and that is my limitation; development has to take place in the execution, in my mind, with my reflexes, etc. Over the years, I have learned that innovation lies in constant and monotonous work and small details. It is the small details that break the bigger system. Looking back at each year, it is important for me to see progress, but also to keep the feeling that it is still the same. That is why I am very careful with each next step.

Why did I step away from video art? I’ve always been drawn to the physical presence of art objects that are constantly pulsating, moving and radiating energy. I don’t know… I even have the feeling that I started with video art by mistake, but now I realise that if I hadn’t, I wouldn’t have come to the point of creating this installation exhibition. Maybe this is the way it’s supposed to be.