Dealing With the Very Different Possibilities of What May Be a Definition of Art

An interview with Valentinas Klimašauskas, Program Director of kim? Contemporary Art Centre

15/09/2017

Early this past summer, the kim? Contemporary Art Centre announced that beginning with August, the Lithuanian curator and author Valentinas Klimašauskas would be taking over as the Centre’s program director. Now the new season at kim? has begun and the first shows have opened, so we spoke to Klimašauskas about his curatorial experiences, his outlook on today’s contemporary art, and the upcoming plans for kim?.

From 2003 to 2013 Klimašauskas worked on the curatorial team at Vilnius’ Contemporary Art Centre (CAC), but he has also put together numerous independent projects and created international solo and group shows. Klimašauskas has also written articles and reviews for several international art publications, including Cura, Dot Dot Dot, Mousse, and Spike Art Quarterly. His book B, an Exhibition Guide In Search of Its Exhibition (Torpedo Press, Oslo), came out in 2014.

“Sparrows”, the CAC Vilnius, 2012. Photo: Dalia Dūdėnaitė

For several years you worked as a curator at CAC, as well as an independent curator. What made you become a curator?

One thing leads to another, and at the end we get something we call “the unknown”. I’d like to think I started at CAC in Vilnius in 2003 as a curator because of my exhibition reviews. However, it could be the allure of being nearer to the artistic domain, or just receiving a job proposal I couldn’t refuse. Or the poetics of that huge, monstrous brutalist building of CAC, pretending to be a neutral white cube. Or my very professional colleagues. Also, I remember being six and asking my mom to let me make my own display of various aromatic soaps that my mother collected. I recall spending hours arranging different packages on shelves, realizing how many possibilities I had. Since then, that feeling of realizing your own limits, as well as the endlessness of the inside and outside worlds, has been both intoxicating and sickening. I intended to impress my beautiful aunt with that display of soaps, as I guess I was thinking that she would find some beauty in it. I still have no idea whom I wanted to impress by becoming a curator. And now it’s too late to impress. As Boris Groys[1] has argued, nowadays everyone is a conceptual artist, arranging images and text on social networks. And we could add to this that today, everyone is even more of a curator as they arrange found objects, texts, images and videos in their social, economic and private lives. Maybe I was just following a general trend?

I assume that your new position will also involve curatorial practice. What do you think is the curator’s responsibility?

A curator’s responsibilities differ in dissimilar contexts. In our neighborhood, I’d like to see more curators fighting for better conditions for artists, better exhibitions (whatever that may mean), transparent and open institutions, and a lucid distribution of funds. In her brilliant book When Attitudes Become the Norm. The Contemporary Curator and Institutional Art, Beti Žerovc[2] spins that not-so-new curator’s chair by making a historical overview of the curator’s position and noticing how the curator became an instrument that the richer classes and the powerful used to softly apply their power and policies in culture. She likens the curator’s position to a pawn’s – as it is used to intermediate between what is authentic (the artistic voice) and the hegemony of the state or capital. Thus, in this context, the curator’s responsibility would mean to: show awareness; (self-)criticism regarding the sometimes invisible but clearly existing contract between an art institution, the state, sponsors, artists, and the audience; and also to rethink and challenge the aforementioned web.

What are the themes or issues that you are interested in as a curator and writer?

I’m interested in various poetic and interdisciplinary entanglements, for example: how beauty seems to appear disinterested but overwhelming; how history copies and pastes itself in formats that become artistic when new media formats are created; and why did the bad, kitschy taste of the 90s became a part of Eastern European identity (and which is still very present in Latvia). Is AI going to be good at art? (Today I read in the news about AI composing classical music as well as human composers do.[3]) If robots take our jobs, will they also steal our pleasures? What about our worries and sorrows? If we teach bots to talk, will we learn their language? Will we understand their sense of poetry? Why do people avoid reality? (“Reality is not a given: it has to be continually sought out, held — I am tempted to say salvaged,” wrote the critic John Berger[4] in his 1983 essay “The Production of the World”.) Is it because we have culture? Can we seek out more of our common reality by doing better shows? Can we distribute the future equally? If yes, would it be really formalistic and boring?

“We are all cyborgs now. To the point where this reality no longer appears at all striking,” writes McKenzie Wark[5]. I’d like to think that contemporary art institutions may help society in creating a common ground in terms of realizing what extraordinary technological, political, social and other changes our societies have experienced in a relatively short period.

“Everybody Reads” night at Nida Art Colony, 2016. Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

On the Internet, I came across the following characterization of your work – “Interested in speculative economies of language, he is into linking concepts and readers into language-based performative systems.” Could you please explain what this means?

I used to curate exhibitions that were organized from a textual position, and I also organized reading nights, such as a series of “Everybody Reads” events – the so-called nights of horizontal readings that were inspired by the idea of “the open work”, horizontal structures, and a quote by Roberto Bolaño[6]: “Reading is always more important than writing”. Everyone attending participates by reading something – a letter, a sentence, a found or written poem, a text message, a short essay, etc., according to a chosen topic. Although the format may resemble a hybrid between Speakers’ Corner at Hyde Park and a meeting of Alcoholics Anonymous, the event generates surprisingly varying collections of opinions, voices and texts that have been chosen or written and read by anyone willing to participate. I can’t wait to start doing it at kim?

You have written a book B, an Exhibition Guide In Search of Its Exhibition. Could you give a short summary of it so as to entice our readers into reading it?

As a young curator working in the provinces (that was before cheap airlines, Google, Facebook, Contemporary Art Daily, etc.), I came up with the rather logical conclusion that the cheapest and easiest way to organize international exhibitions is to use easy-to-transport textual, language-based works using only copy-and-paste functions; and so I decided to “curate” texts as exhibitions. Thus, the book is the result of these efforts and collaborations with other artists and writers and, as truthfully advertised, it contains written exhibitions that float in time and space, either with or within a joke, in one’s mind, on Voyager 1, in Chauvet Cave, or inside the novel 2666 by Roberto Bolaño.

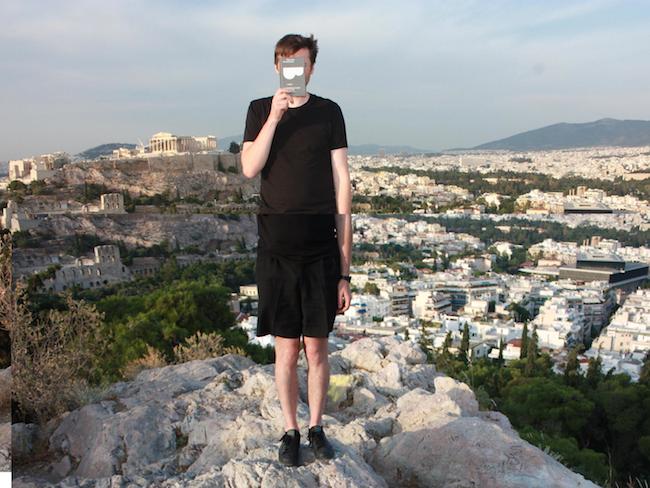

Valentinas Klimašauskas’ “B and/or an Exhibition Guide In Search Of Its Exhibition” (Torpedo Press, 2014) in Athens. Photo: Salomėja Marcinkevičiūtė

How do you feel about what is happening with contemporary art right now? People are talking a lot about how there haven’t been any radical new phenomena or directions in the past ten or even twenty years. Do you agree with that?

I categorically do not. Even if someone were to make art in the same way as in the last century, it would have a different meaning, and thus would be different. One of the most important components of the art world – the audience and the context – has radically changed. The world today is very different from what it was five, ten or twenty years ago. Just listen to the news. We are constantly reminded that we live in the age of the greatest climactic, conceptual, economic, political and social arguments, controversies, differences, etc. known to recent history; when some scientists speculate that the Universe might be just a hologram[10], and counting. We are constantly reminded that we are and will be experiencing the exponentially growing consequences of global warming, and we muse about its causes, consequences and retaliation. Thus, while I am quite far from finishing the list, when concepts like hyper-objects are traversing the universe as we know it (and as we don’t), how is it that one can think that there are no radically new phenomena in exhibiting, making, or understanding art? The ways in which the art world is organized are always shifting; for example, racist colonialist history is being critically rethought and rewritten; the hegemony of the Western world and patriarchy are being actively revoked. I hope kim? and its audiences will dynamically participate in the aforementioned processes.

What are your personal goals as you begin working with kim??

To add some controversy or points for further discussions, I’d like to point out that in the 90s, contemporary art in the Baltic countries was seen as a tool with which to “Westernize” and “modernize” our countries; although never very well supported or popular, it did, however, have an aesthetic and political appeal. And our countries have already moved into a new era now. The function and meaning of contemporary art in our societies has changed. After entering the EU and NATO socio-politically, our societies do not vocalize any new political aims except for economical ones. I don’t really hear any ideas about a forthcoming social utopia coming from our politicians; and the Baltic countries are still pretty nationalistic, homophobic, racist, and anti-immigrant. The idea of “modernization” is left to the private sector and investors, and in this context, it mostly means neo-liberalism and further privatization of the social sphere. At the same time, some political parties express reactionary and traditionalist feelings, and recent events in Hungary and Poland foreshadow the dangers our rather young democracies might meet one day. As we know, at least since Pierre Bourdieu[11], culture is very well connected to the concept of class, and our societies, sadly or not, are transforming into class societies. This process has already happened in the West, but we still have a chance to try our best to confront this tendency.

However, our scenes are also very different from those of our Western colleagues. For better or worse, our contemporary audiences are not big enough to perceive it as an anonymous mass – we may really have an impact on the local scene, but also, we may be visible internationally while promoting the Latvian and the Baltic scenes in general. Wonder if it sounds personal enough?

“CLOUD DATING IN THE AGE OF (UN)CONTROLLED PRECIPITATION” on www.vokai.io

For the past eight years, the exhibition program of kim? had been focused mostly on conceptual art, young artists, and new works. What will be your strategy for the kim? exhibition program?

To single out an example, I am looking back with pleasure to the 60s, when post-war artists were still as yet not seeking to sell, but to challenge artistic and social norms and standards, to communicate – although most often with no success at all with wider audiences. Think about Allan Kaprow[12] and his idea that life is more interesting than so-called Art art, or George Maciunas[13], who thought big and idealistically planned to establish a cooperatively-run Fluxus Island on one of the Virgin Islands called Ginger Island. As this plan did not succeed, he was more productive with his Fluxhouses Cooperative project in SoHo in 1966, converting warehouses into living and working spaces for artists; although later, this indeed served to gentrify the neighborhood, maybe even originating the phenomenon itself, even though it went against Maciuna’s own designs.

This higher utopian vision is what contemporary art institutions were and are lacking in the last decade, on a global scale. They are trying to find, once again, their new function in society’s heart while, at the same time, they are immersing themselves into or are analyzing very important global issues such as right-wing populism, climate change, the Anthropocene, post-Westphalian geopolitics, etc. However, it often just looks like artificial and fashionable rhetoric; so, how do you make it sound real, inviting, and important locally? This is a huge and problematic, but meaningful, undertaking.

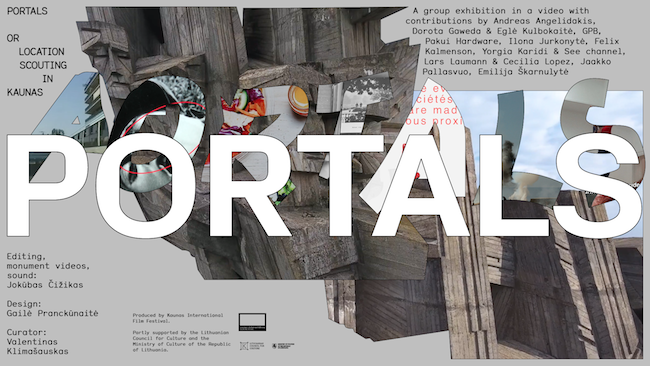

A group exhibition in a video: Portals … or location scouting in Kaunas

What do you mean by “the concept of global asynchronicity as a juxtaposition of diverse, sometimes even mismatched, discourses and narratives”? (taken from your statement in kim?’s press release)

I like to use this rather popular expression by William Gibson[14] to describe contemporary life – “The future is already here, it’s just not equally distributed”. So let’s think about the “now” as a kaleidoscope of various narratives and times mixed together – there are a few who live like they do in Silicon Valley, creating apps and capitalizing on that, while within a five-kilometer radius from their suburban houses you may find farmers living almost like they did back in the 19th century; others are stuck in the Cold War times, in their block houses; or are fighting neo-liberal or feminist wars with the patriarchy and new reactionaries on social forums online – it seems that for today’s society, it’s almost impossible to find a common ground. This definition also suits the art scene – you may find various aesthetics from 19th-century symbolism and simplistic 70s conceptualism to post–accelerationism and new materialism, now being practiced by students at the same art academy or in different galleries located on the same street. Having made studio visits from Reykjavik to Athens to Helsinki over these last years, I think this asynchronicity is global.

However, I don’t see this asynchronicity as something negative or untimely – I’d like to embrace it in creating a curatorial model in which all of the perspectives may come together as manifestations of diversity and, hopefully, as new friendships and collaborations. I like to think about the models in terms of “distributing the future equally”, but I also see the value of being non-synchronised with art scenes in Beijing, Berlin, or NYC.

Thus, I’d like to propose a curatorial program based on asynchronicity; a juxtaposition of the very diverse; a collaboration of the dissimilar, and, at first sight, the un-matching; a program based on the idea of connecting the very various notions of what contemporary art may stand for or be described as. Isn’t this also programmed into the name of kim?? Think of the different clocks in a hotel lobby showing the different times in various time zones – however different the positions of the clock hands may be, they still refer to the same global time, no?

Will there be any significant changes in the working model of the organization? For some years now, kim? has been taking an active role in the international promotion of local artists by organizing exhibitions for them abroad, arranging studio visits for international curators, creating a residency program in collaboration with international institutions, and so on. What are your plans regarding the international promotion of Latvian contemporary art and kim? as an institution? What are kim?’s plans regarding collaboration with independent curators?

It’s my first weeks in Riga. I’ve only started meeting artists, visiting institutions, and even talking to strangers on the street or in a bar. I’d like to listen first – for advice, and to find out the relevant needs and wishes – and then make real plans later. However, I may assure you that we have many ideas and proposals on our calendar, and a list of friendly institutions worldwide who are willing to collaborate. Kim? is and will stay an open institution for proposals, and it is willing to invite artists, non-artists, writers, philosophers and other cultural producers to collaborate in our projects, both at kim? and abroad.

A group exhibition in a video: Portals … or location scouting in Kaunas

In an interview for Arterritory, Zane Čulkstēna says that kim? Has always been interested in attracting as large an audience as possible. How important is it for you to reach out to a broader audience and make an impact on how things are approached/perceived in society?

The real danger of contemporary exhibition-making is in ending up with the wrong audiences, as Brian O’Doherty[15] already concluded in the 70s with his seminal work Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space. To summarize, the general audience has never been alienated from contemporary art as much as it is now; the new formats of exhibition-making should not focus just on the rich, on the few highly-educated and privileged people who collect art or are able to pay for vast white spaces, and who affirm the art system. Otherwise, at the end, you exclude your fellow neighbors from a block house, or the multitudes that you may meet in a tram, but not those at an opening or a conference. If we fail to connect to wider audiences, we will all meet in some white-cube gallery opening, adding to the gentrification of the neighborhood; or in line at some hyper-museum, as tourists who are there to increase the ever-growing institution’s attendance numbers.

The name “kim?” is an abbreviation of the insistent question “What is art?” in Latvian (kas ir māksla?). What is art?

I’m not sure yet what art is in Latvian, but there were many disputes about the same issue in French, for example. While on the beach in Nice in 1947, three artist friends rather boyishly and egocentrically choose to “divide the world up” between them. Fernandez Armand[16] got the land and its riches, Claude Pascal[17] got the air, and Yves Klein[18] got the sky and its infiniteness.

When another French artist, Robert Filliou[19], said that “art is what makes life more interesting than art,” another French artist, Benoît Maire[20], replied a few decades later that “art is what makes art more interesting than life”.

Around the same time, the whole world started to become a white cube and the white cube lost it walls. According to Marshal McLuhan[23] (1931–1965) introduced his “Live fingers”, a new form of art, as he declared, that was achieved by pointing his finger at people on the street and declaring that they were his works of art. And this was not the beginning – as early as 1954, Greco claimed that he had started signing “walls, streets, and bathrooms in Paris”. He also claimed to have signed the whole city of Buenos Aires in 1961; however, there is no way to prove this.

In the context of these examples, all of which show that the art world was and still is very much about dividing and owning, we should remember the following overused but democratic and liberating quote by Joseph Beuys[24]: “Even the act of peeling a potato can be an artistic act if it is consciously done”.

And I’ve only quoted a few white male artists who were having a dispute after the Second World War. I’d like to think that every show at kim? will continue illustrating the very different possibilities of what may be a definition of art, and that they will also include AI, animalistic, feminist, eco, LGBTQI, nonhuman, non-Western, posthuman, robotic, and other perspectives.

Valentinas Klimašauskas at kim?. Photo: Renāte Prancāne

[1]Boris Groys (1947) – born in the USSR, resides in Germany; art historian, media theoretician, philosopher, specializes in Slavic studies; professor at several European and US universities.

[2] Beti Žerovc – Slovenian art historian and theoretician, educator in the Faculty of the Arts at the University of Ljubljana; author of several books on the role of the curator in contemporary art.

[3] futurism.com/a-new-ai-can-write-music-as-well-as-a-human-composer/

[4] John Berger (1926–2017) – English art critic, writer and painter; his essay “Ways of Seeing” (1972) has become a standard academic text.

[5] McKenzie Wark (1961) – Australian-born author and scholar of media theory, critical theory, and new media; well-known works are A Hacker Manifesto (2004) and Gamer Theory (2007).

[6] Roberto Bolaño (1953–2003) – Chilean writer and poet; his most internationally well-known work is the posthumously published novel 2666 (2004); in 2008 he was awarded the National Book Critics Circle Award for Fiction (USA) for 2666.

[7] www.nature.com/news/simulations-back-up-theory-that-universe-is-a-hologram-1.14328

[8] mitpress.mit.edu/books/stack

[9] Westphalian sovereignty is the principle of international law that each nation-state has sovereignty over its territory and domestic affairs. The Peace of Westpahlia, signed in 1648, ended the Thirty Years’ War, and is believed to be the impetus for the modern international system of states. Since the end of the 20th century, Westphalian sovereignty has been widely seen as becoming anachronistic due to globalization and international terrorism.

[11] Pierre Bourdieu (1930–2002) – French sociologist, anthropologist, philosopher and public intellectual whose main field of interest was the dynamics of power in society; his best-known work is La Distinction. Critique sociale du jugement (1979).

[12] Allan Kaprow (1927–2006) – American painter, assemblagist, and pioneer in performance art and installations.

[13] George Maciunas (1931–1978) – Lithuanian-born American painter, one of the founders and most active members of the Fluxus artists group.

[14] William Gibson (1948) – American-born Canadian writer, widely regarded as the inventor of the cyberpunk genre.

[15] Brian O’Doherty (1928) – Irish-American art critic, author, artist and educator; his collection of essays, Inside the White Cube: Ideologies of the Gallery Space (1976), has become a canon of art history; has written several novels.

[16] Armand Fernandez/Arman (1928–2005) – French-born American painter known as “Arman”; one of the founders of the Nouveau réalisme group.

[17] Claude Pascal (1921–2017) – French composer who worked in practically every musical genre; professor at the Paris Conservatoire and music critic for Le Figaro newspaper.

[18] Yves Klein (1928–1962) – French artist, leading member of the Nouveau réalisme group; regarded as one of the first performance artists, as well as an inspiration to minimalism and pop art.

[19] Robert Filliou (1926–1987) – French Fluxus artist, author of films, videos and happenings, sculptor and “action poet”.

[20] Benoît Maire (1978) – French artist working in film, sculpture, painting, photography, collage, and performance art. Known for his views on theory as an independent art form.

[21] Marshal McLuhan (1911–1980) – Canadian professor of media theory, philosopher, and public intellectual; coined the expression “the medium is the message” and the term “global village”.

[22] https://marshallmcluhanspeaks.com/interview/1972-the-planet-as-art-form/

[23] Alberto Greco (1931–1965) – Argentinian artist and poet; spent most of his life in Spain; having started with painting, he moved on to conceptual art, and is now regarded as a pioneer of Spanish conceptual art.

[24] Joseph Beuys (1921–1986) – German artist and theoretician; one of the most influential authors of the second half of the 20th century.