'Act early, decide quickly, have a good eye, and be brave'

An interview with Polish art collector Piotr Bazylko

Piotr Bazylko is one of the most interesting and inspiring art collectors not only in Poland but in the whole region of Central and Eastern Europe. This assertion is not based on the scale of his collection (which has approximately 600 works of art – a quite respectable figure but not necessarily mind blowing), nor on the private museum dedicated to representing him (which does not exist and has not even been planned as of yet). Instead, it lies in the fact that Piotr is not only an expert of contemporary Polish and East European art and a collector of this art, but also an individual who deems it important and interesting to share his own experience. Having a journalistic background (in TV and printed media, and as a former head of Reuters Polska), he and his ‘partner in crime’, Krzysztof Masiewicz, with whom Piotr became friends after initially getting to know him as a collector, spent ten years running the ArtBazaar blog on art collecting. In 2008 they jointly published the book The Contemporary Art Collectors’ Guide in Polish, which represents the essence of their experience and a sort of interpretation of the local art scene. That was a time of a real uplift for Polish art: new museum collections and new galleries were springing up in the biggest cities all over the country, local artists (Wilhelm Sasnal, Mirosław Bałka and many others) had begun gaining international recognition, and Polish art acquired the status of an ‘export product’.

More than ten years have passed and the book has now become a bibliographic rarity. A new version of The Guide was printed in December 2019, its text almost entirely reworked and a whole lot of new experience reflected within its pages. The book represents an insiders’ view on collecting art, making public the knowledge accumulated by its two authors who have no art-related degrees but whose interest in and dedication to contemporary art is extraordinary. In the introductory part of the book, Piotr and Krzysztof write: ‘Collecting art is an adventure that can truly change your life. We can’t imagine living without art in our homes every day. We can’t imagine not meeting other collectors and people we’ve met thanks to art. Nor can we imagine life without interacting with gallery owners. Collecting contemporary art is more than just collecting art – it’s collecting priceless experiences... Whatever the main motive for buying a work of art or building a collection is, remember that its primary purpose is to bring us joy. Collecting helps us better express our personality and our way of seeing the world while helping us to communicate with others and show off our aspirations. It allows us to experience special moments – the emotions that result from buying a long-sought-after work, as well as the camaraderie of meeting other art collectors. And finally, what we’ll most begin to appreciate in the fullness of time will be the “heritage” we leave for future generations’.

I was introduced to Piotr in September 2019 during Warsaw Gallery Weekend, when both of us took part in a discussion supported by the Adam Mickiewicz Institute on the role of collecting art on the scale of Central and Eastern Europe. All of the participants of the discussion panel had gone strolling through galleries, and we met again just to go see the winner of the event – the work Blacksmiths (Kowale) by Mikołaj Sobczak in the New Kingdom exhibition organised by the Polana Institute. With excitement and his own authentic form of knowledge, Piotr verbally expressed to us how he contemplated this painting full of symbols and allusions to Poland’s recent past. Being informed and possessing the skills to work with information are what he considers extraordinarily important professional qualities. After leaving journalism, he switched over to the sphere of public relations and became a partner and co-owner of the media consulting company Bridge, which has approximately 60 works of art from his collection hanging on the walls and standing in the corridors of its offices on Zielna Street.

Around 100 more works of art have, in a witty and tasteful way, found a place in his private home in the capital city’s Żoliborz district; built in the 1930s, the house is where the imperial garrison had its training grounds before World War I. The mutual interaction one senses between art and space – both physical and functional – in the house of Piotr and his wife Alina Prawdzik (who is VC investor and member of the board) is a story that deserves a documentary feature of its own. Consisting of paintings, graphics, objects, and even video works, Piotr’s collection has several directions: thematic ones like those that play around with Polish national symbols, and those that are associated with format. For example, Piotr collects musical and sound recordings created and distributed by artists; included are exhibition catalogues from collaborations between artists and musicians (Andy Warhol and The Rolling Stones, Robert Rauschenberg and Talking Heads, Damien Hirst and Red Hot Chilli Peppers, etc.), LPs, CDs, cassettes, and even USB memory sticks.

We went to the home of Piotr and his family during the latter half of the day. The first half of the day – almost immediately after my arrival in Warsaw – was spent in a room at the Bridge agency. The conversation began with a discussion about the works of art on view in the agency’s offices.

Piotr Bazylko. Background: Dan Perjovschi, Drawings from Venice Biennale, 2007. Photo: ® Szymon Rogiński

In the meeting room of the agency of which you are a co-owner, and where a part of your collection is on view, there are several works of art associated with the Holocaust. This seems a rather unorthodox space in which to present works of such a nature – they are quite dramatic…

And they are not pleasant, are they?

Exactly.

But you need to go into it to be able to get to the essence; you need to sink into it because they are rather beautiful on the surface. A group of people, buildings, surrealism... If you do not know the context, everything seems rather beautiful. This is characteristic of contemporary art – without context, it can look quite nice. However, add a context and everything changes. I wanted to add works of art to this space that would say something about us as a company. We work in public relations. We work with government institutions, among others; we communicate with people and we relate to current events, which sometimes are good and sometimes are not good at all. This provides an appropriate environment for choosing works of art of that kind. Life is not very nice in fact, especially if you have to follow the political situation. So why exhibit some sort of flattering art there?

You began your career as a journalist, and you very much worked with information and conveying information to people. Did you feel any kind of influence from contemporary art at the time?

I would not say so. Of course, I attended exhibitions and museums of modern and contemporary art. We had a few paintings at home. But I was rather far from collecting at that time. Changes happened during the last years of my career in journalism, when my wife gave me a present – she sent me to a class about art photography. After that I began buying black-and-white photographs, and several items of from that time are still part of my collection. Then, a real revolution in the sphere of art took place in Poland. It was, in essence, due to the activities of the Raster Gallery and the Ładnie Group, which included Sasnal, Bujnowski and Maciejowski. All of that somehow had a profound impact on me.

Wilhelm Sasnal. Bez tytułu (No title). 1999. Photo: Daniel Rumiancew

When exactly was that?

During the transition to the new millennium. Probably in 2000, maybe 2001… The artists I am talking about were very close to my generation, just a few years younger than me. And they were talking about issues and the things that were going on around us. They were talking about how capitalism is changing the world around us – about how, on one hand, it gives us freedom, but on the other, it makes us vulnerable through the things that we crave. That was art about all of us, about the ways we were at the time – me included. That is where the urge to collect appeared from.

What were the first items of art in your collection?

Usually collectors feel a deep emotional attachment to their first items while, at the same time, these items are seldom the most important ones in their collection. I would say that Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, a painting by Marek Sobczyk, was my first item of that sort. It was hanging on my wall for some time, but I would not say that it is the kind of painting which I would like to cohabit with. It does not speak to me like it used to. However, it still remains part of my collection and it is important to me as my very first choice.

But do you remember what you felt when you hung it on the wall for the first time?

I rather remember what I felt during the visit to the artist’s studio. How I was looking at the paintings, how difficult it was to make my choice, the smell of the paint… I also recall my considerations – is my wife going to agree with my choice? Or, when the painting was already selected, doubts were still springing up – maybe I should have picked a different one… The studio was situated in the basement of a house in Ursynów, a new district in the south of Warsaw. The painting was comparatively medium in size and it could easily fit in my car, therefore I did not have to organise its delivery. I remember all of this very well.

Many collectors of paintings speak of a mystic power that they have. Do you feel a fundamental difference between works of art based on whether they are expressed through painting, photography, or any sort of art object for that matter?

I like figurative painting. And I like to touch a painting that has been painted in oil. Acrylic has a completely different feel – it is flat. Paintings in oil have their own individual surface, and you can feel it. When I am in a museum that has paintings, I like to get as close to them as possible and try to examine the surface. I do not like paintings under glass for this reason. Indeed, painting possesses some kind of mystique. Of course, there are sculptures in my collection, there are objects, there are new media (photographs, video works, sound works), but it is paintings that represent the essence of art to me.

Katarzyna Przezwanska. Fotel (Armchair). 2013–2019. Photo: Daniel Rumiancew

Have you experienced the situation of buying a work of art only to later understand that it is difficult to coexist with its energy, its aura?

Recently I did have such an experience with a young artist, Martyna Czech. I bought several of her paintings; three are hanging in my office (Eye, Rose, and Fallen Angels), and one is at home (Self Portrait). Her paintings are about her feelings, and these are very powerful and dark feelings. I like her paintings very much, but some of them are simply too powerful to be exhibited in a space where you spend a lot of time. They are excellent and I have no intention of getting rid of them. But I am keeping them in my warehouse. There is so much dark energy there and strange feelings towards other people and towards the author herself. Art does not necessarily have to be inappropriate or brutal to make it difficult to coexist with it.

Do you buy works of art from artists or from galleries?

I buy from different sources. If an artist is not represented by a gallery (and that was the case with Martyna – she was still a very young artist studying in the Academy), I buy directly from the artists. However, if an artist works with a gallery, I always deal with the gallery. I feel it is my duty as the collector to support galleries. From time to time I also buy through auction houses and dealers, but not too often.

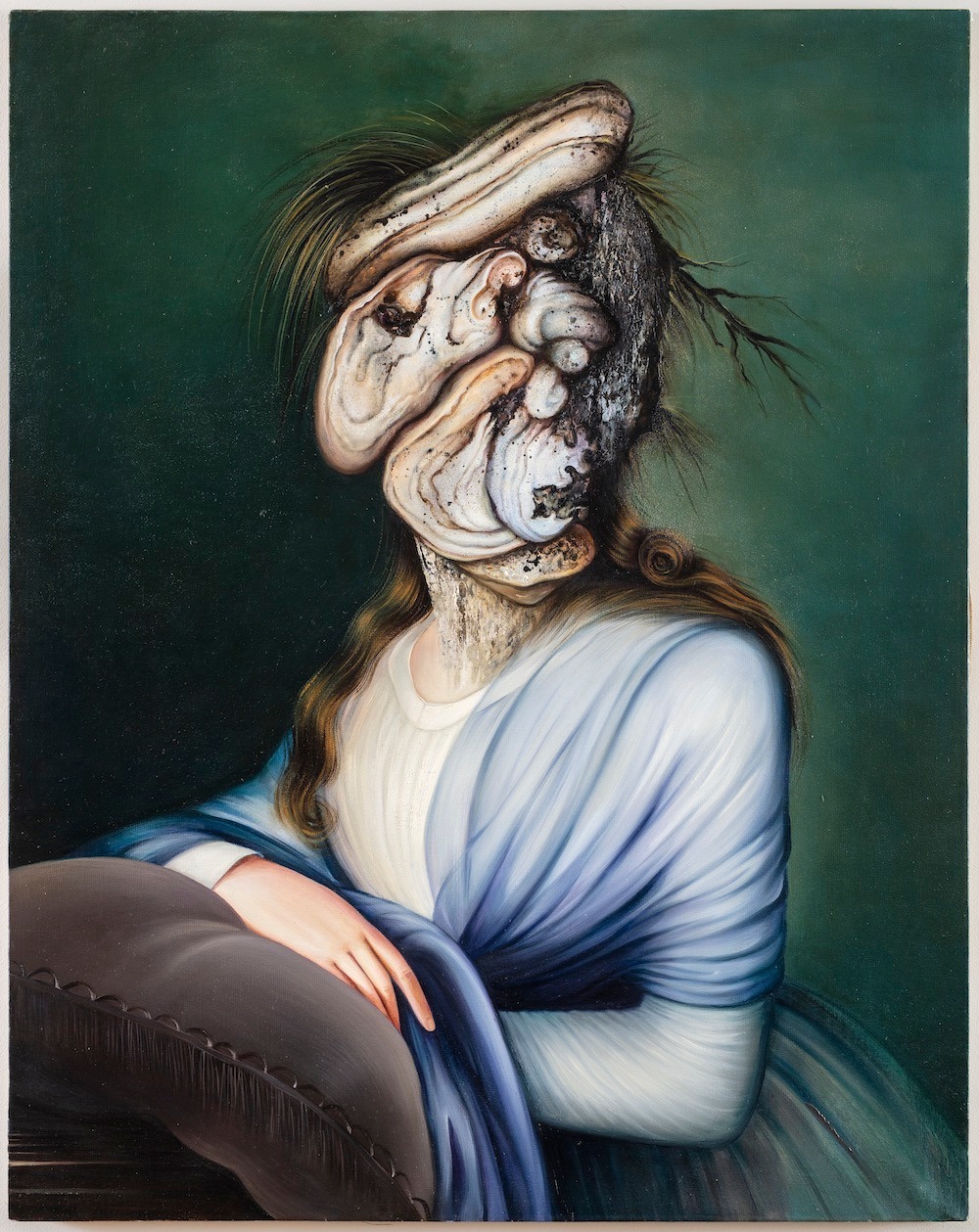

Ewa Juszkiewicz. Portret damy (Portrait of a Lady). 2013. Photo: Daniel Rumiancew

Concerning auctions – do you have your own preferred strategy?

I do not attend auctions myself. I buy either via telephone or online. That’s because it is easier to say ‘no’ this way – you do not feel the passion growing in the room where the auction is taking place. There have been a couple of cases when I wanted to buy a particular piece of art so badly that I simply bid too high. Usually, if the price is more than I can afford, I take it easy – there will be other auctions, other works of art, other opportunities. This is the way I usually buy art by modernists, and they are not essentially ‘critical’ for my collection dedicated to contemporary art. But there are authors who are important as a kind of landmark or point of reference – Andrzej Wróblewski, Jerzy Lewczynski, Erna Rosenstein, Julius Koller, and Miriam Cahn.

Do you have any personal contact with the artists whose works you collect? Is this aspect of collecting important to you?

I like to have that. One artist, Robert Maciejuk, would come to our home on a regular basis – we cooked food together; this lasted for several years. These dinners usually went on until two or three o’clock in the morning. We were dead the next day, but we had to go to work anyway. For me, the possibility to meet artists – to talk to them, ask them questions – constitutes an important element of delving into contemporary art. After all of that, you start seeing beyond just art itself – you start seeing the imprint of the artists’ personalities.

But there are collectors who say that they try to avoid such contact; they try to avoid forming any personal impressions of the artist…

Sometimes such meetings can bring disappointment, as in when the artist has, in principle, nothing to tell about his or her work. But this does not necessarily automatically mean that the work of art itself is poor; it may simply be that the artist may not be strong in communicating and perhaps expresses all of their reasoning through their art. There have been times when I have met artists in person and after which I stopped collecting their works. But such cases are very, very rare.

Do you look for something specific in art – some sort of drama, conflict…?

A work of art needs to talk to me. It can be a story associated with its making or its fate. It can be something about the technique the work has been created in. It can be the artist themselves… On the other hand, I can tell from my own experience that the more the work of art grabs my attention at the very beginning, the less interest I have in it afterwards. It is usually a good sign if I am not absolutely fascinated by it upon first sight and instead, as time goes on, there are layers that the work possesses and these gradually begin to reveal their existence. These can be details that suddenly change your ‘reading’ of the work. In any case, it should be something interesting, something that is not obvious, a thing that does not grab your attention at first sight. By the way, I do not buy for the sake of the artist’s name. If a work does not ‘talk’ to me, I am not going to buy it – even if its author is a celebrity in their sphere of art.

Mikołaj Sobczak. Barricade. 2016. Photo: Daniel Rumiancew

When did you decide to share with others your experience of collecting?

About 15 years ago, several articles about art investments appeared in Polish papers – about collecting as a way of investing. Names and dates were usually mixed up in these articles, as they were written by people with little knowledge of the subject. Then Krzysztof Masiewicz and I decided that something must be done with this situation in order to clarify some things and at the same time inspire other people to collect art.

I have been collecting art for about 20 years now, and it turned out that such a decision was made after approximately five years of experience in the field. My knowledge was not bad at all already at that time, but definitely not as broad as it is today. I am still learning and finding out new things about collecting and the art market. As a collector, you must continually keep supplementing your knowledge.

I do not know how many collectors of art there are in Poland, maybe 100 or twice that. This cannot be called a ‘success story’ for such a big country and a sufficiently important member state of the EU. There is plenty to do in this sphere… People liked what Krzysztof Masiewicz and I figured out and offered, I think. It was liked not only by collectors or those knowledgeable about the subject – artists and curators liked it, too. Our ArtBazaar blog was quite active and there were people who told us that their day begins with browsing through our blog – just to see if something new had been published.

What were you writing about in the blog?

About how to collect art. About auctions in Poland and internationally. About what is happening in the world of art and in the art market. About Polish artists abroad. We produced a series of interviews with collectors, artists, gallery people. A very broad spectrum of things.

More than one thousand posts were published, as far as I understand…

Yes, approximately. The blog was active for about ten years.

And then the idea about putting together a book appeared. Was this also a joint project?

Yes, we do everything together: write about contemporary art and collecting it, organise small exhibitions, etc. We have even launched our own record label, called ArtBazaar Records, with which we publish recordings done and decorated in a special way by artists.

Co-authors of the “The Contemporary Art Collectors’ Guide” Krzysztof Masiewicz and Piotr Bazylko

Was coming out with a book an offer from a third party?

Yes; at the beginning it was not even a book but something more like a brochure. It turned out to be so popular that we were asked to write a whole book. It was published in December 2008. And people have still been trying to buy it although it’s old and many things have changed and happened since then. Therefore, we decided to publish a new and renewed edition, which was published in December 2019, exactly eleven years after the first edition.

What sort of changes were included in the new edition?

We wrote most of the new book from scratch. After all, we had to translate an additional eleven years of our combined experience into a new text. We also decided to pick a different concept for the new book and to talk about particular works of art rather than artists. So, the second edition has a section titled ‘The 75 most interesting works of Polish artists in the 21st century’ – beginning with the year 2000 and ending with 2019.

It’s turned out to also be a sort of tour of the contemporary Polish art scene.

Indeed. And there is more than only paintings, sculptures and installations in it. There’s an Instagram account, a photobook, and audio recordings. Anything can be art, and it can play a role that is important and even legendary, in a way.

How has the art scene changed over the last 20 years?

It has become much more professional. There were only a few galleries 20 years ago. There are about thirty in Warsaw alone now. Polish artists are included in the collections of key contemporary art museums around the world. There have been many positive changes. However, the number of collectors is still comparatively small, and they mostly collect Polish art. This does not have a good influence on local art – the perspective and the context are lost. Thus, notwithstanding the extensive progress that has taken place, there is plenty to do still. And more in the sphere of collecting than in the sphere of the work of art galleries.

At the same time, the best-known Polish collectors are opening their own museums, but not in Poland…

Yes, in Germany (Werner Jerke’s in Reclinghausen) and the Susch Muzeum by Grażyna Kulczyk in Switzerland. From a global point of view, opening the museum in Susch instead of in Poznan or in Warsaw, as earlier planned, might actually have a positive influence on the Polish art scene due to the fact that it is a really international museum in which Polish art is presented in a global context. But from the point of view of local collectors and spectators, it is not that great since you cannot see this art in Poland itself anymore. And to add more bad news – there is no permanent collection of Polish contemporary art in Warsaw that is currently open. The situation will change in 2022 when the new building of the Museum of Contemporary Art will be finished. But this is only going to happen in a couple of years!

Why did those museums not open in Poland after all?

Art is not considered to be an important matter here. For local politicians, it is more important to build a new football stadium instead of a new museum. I tried to analyse the situation a few years ago and took a look at the 100 richest people in Poland as reported by Forbes. Nine persons out of these one hundred were investing in football clubs, and only two were supporting art in some way. This speaks volumes about what place art has in people’s perception. It is sad and is has to change, and that’s why we decided to rewrite the book – to provide a stimulus to new collectors just beginning to get into this business.

Andrzej Wróblewski. Dziewczynka (Girl). 1956. Photo: Daniel Rumiancew

How do you see this new generation of collectors? How are they different?

They are very different! They like to show everything that they buy on social media. I do not have the courage to do this (laughing). Krzysztof Masiewicz and I write about art, but we do not publish photographs of the works we have purchased, tagged with ‘What do you think of it?’. However, I do not think that what they are doing is wrong; sometimes I learn from them. But it is a completely different approach, I think. And they are generally more open. They are enjoying art and showing it to everybody, while we are also enjoying it, but…not showing this as directly as they are.

Are they interested in art related to new formats and technologies? Or is it too soon to be making any generalisations?

Yes, it is too soon, I think…

I interviewed the well-known German collector Julia Stoschek, and she said that for her, an interest in time-based art and the moving image is absolutely natural as she grew up during the rise of video clips and MTV.

I think that if my son becomes a collector in the future, he will definitely collect videos instead of paintings. When we go to exhibitions, he is not very interested in the paintings and photographs, but as soon as he notices that a video is on exhibit, it immediately grabs all of his attention.

Interestingly, two or three years ago there was much hype being generated around virtual reality. I recall an English curator who specially travelled across the Baltic States in search of artists working in this direction. Strangely enough, I have not managed to stumble upon something truly interesting and revolutionary that has been made using this technology. As a form of entertainment – yes, but no more than that…

Perhaps they will never appear. Both the good and the bad characteristics of the future stem from the fact that we do not know what it is going to be like.

Miriam Cahn, OT (No title), 1976/2003. Photo: Daniel Rumiancew

What do you think – are there more female representatives among the new generation of Polish collectors than previously?

I hope so. Not only because of the lack of female collectors in Poland (and in fact, in all of Eastern Europe), but because a larger number of female collectors will also help female artists. If we look at some of the most important things to have taken place over the last five years, they are mostly related to female artists. We are a rather conservative country, but because of real socialism, women began working properly – there weren’t any women in my parents’ generation who sat at home doing only household jobs. Changes continue to take place in this direction. A larger number of female collectors would help support young female artists; it would also encourage them to not leave the profession as they near their thirties, which is what often happened in the past.

You referred to the socialist past of Poland. At the recent summit of collectors that took place during Warsaw Gallery Weekend, you said that a common past still unites Eastern Europe. Simultaneously, you encouraged Polish collectors to think on a more regional level…

Yes, at least on a regional scale. I don’t think they should stop there. It is important to not forget about the global context. However, I think that it is interesting and natural to be looking at Polish art from the point of view of the Central and Eastern European context. Notwithstanding the differences, we still have many things in common. The communist past is one. Another is the social position of women thanks to the role that they played in communist society. A third one is the phenomenon of American-style capitalism that we experienced in the 90s. All of us were caught up in it… So, the attempt to think regionally is very reasonable, and it is also a good first step towards a more global approach.

Tomasz Kowalski. Bez tytułu (Odwórcony krajobraz #1) [No title (The reversed Landscape #1)]. 2007. Photo: Daniel Rumiancew

In what ways are you implementing this ‘regional approach’ yourself? Do you attend, say, the viennacontemporary art market, which specialises in art from the region?

Yes, the viennacontemporary is an outstanding place to get an understanding about what is going on. Many interesting galleries, especially the new ones, exhibit works there. Another ‘regional approach’ opportunity is to follow what is happening in the key galleries in the region. And then there are the auctions, of course… The internet provides massive opportunities – it is not even necessary to go somewhere to find out something new. On the other hand, since around 2006, Polish galleries have been doing joint projects with galleries from other countries in the region through which they invite the other country’s artists over for special exhibitions. This is how I came to buy my first international work, Communism Never Happened by Romanian artist Ciprian Mureşan, without even leaving Poland – it was on view during an exhibition within the framework of the Villa Warsaw project.

However, when buying an artwork by, say, a Slovak artist, you most likely need to have some sort of awareness of the bigger picture, i.e. knowledge about the country’s art scene and that particular artist’s place in it…

Yes, you need to do some investigation, of course. However, a fundamental advantage lies in the fact that over the past 10-15 years, the works of key figures from the art scenes of the region have been quite accessible to ordinary collectors (in terms of financial capability), although the situation is changing now because they are increasingly attracting an international level of interest – they are being included in the collections of museums such as MOMA. This, however, is more applicable to ‘established’ artists who have a historic context. Things are slightly less definitive when in comes to younger artists, but if you manage to establish relationships with one or two galleries in each country, you will get a reasonable understanding about what is happening there, what is important.

Are there any thematic regional parallels besides the days when ‘capitalism ran wild’?

Yes, there are other connections. Even considering that every country that was in the socialist bloc had its own specific characteristics in terms of politics, special issues, the relationship between cities and rural areas, and so on. One thing that they all have in common is the way that people see art and the role of art in society, as well as how the artists there interact with society and portray social issues through art. Even under the communist regime, artists, in a way, lived within their own camp in which they were afforded more freedoms than others. Now we are bound by an interest in our past, an interest in the social and political changes that we underwent, and the whole topic of emigration and the movement of people. The entire region is facing these issues and the art reflects that, without a doubt.

Not many projects dedicated to the ‘regional dimension’ are entering established national art institutions. Perhaps collectors can trigger the process?

Maybe, since collectors usually react and act more swiftly than public institutions. If I can afford to buy a particular work of art, I can make my decision almost immediately. But for an institution it is a long and bureaucratic procedure. It’s the same situation with exhibitions – these are processes that take more than a year to prepare. For a collector as a private person, however, the most important things are to act early, decide quickly, have a good eye, and be brave.