I am very suspicious of a global art market machine

An interview with Daniel Hug, the director of Art Cologne

15/01/2018

Upon meeting Daniel Hug, the director of Art Cologne, last summer, I remarked: ‘I’ve heard that your ideal house would be something like Casa Malaparte, the house built by the Italian writer Curzio Malaparte on the Isle of Capri. Is that true?’ ‘Yes,’ he answered, ‘I could build my Casa Malaparte here in Latvia, in Jūrmala, among the pine trees.’

We had met up in Riga, a city he tends to visit rather regularly. Yet this is only one of many places in the world which Hug could call a frequent stop, since he is quite the cosmopolitan – a fitting image in this era of globalisation. He was born in Europe (Switzerland), grew up in the US Midwest (Chicago), moved to Los Angeles, and then returned to Europe, but this time to Germany. He tends to laugh a lot and joke around, as well as point out the ironic, but as a whole, he leaves one with the impression of a very goal-orientated person who is pleasantly open and direct.

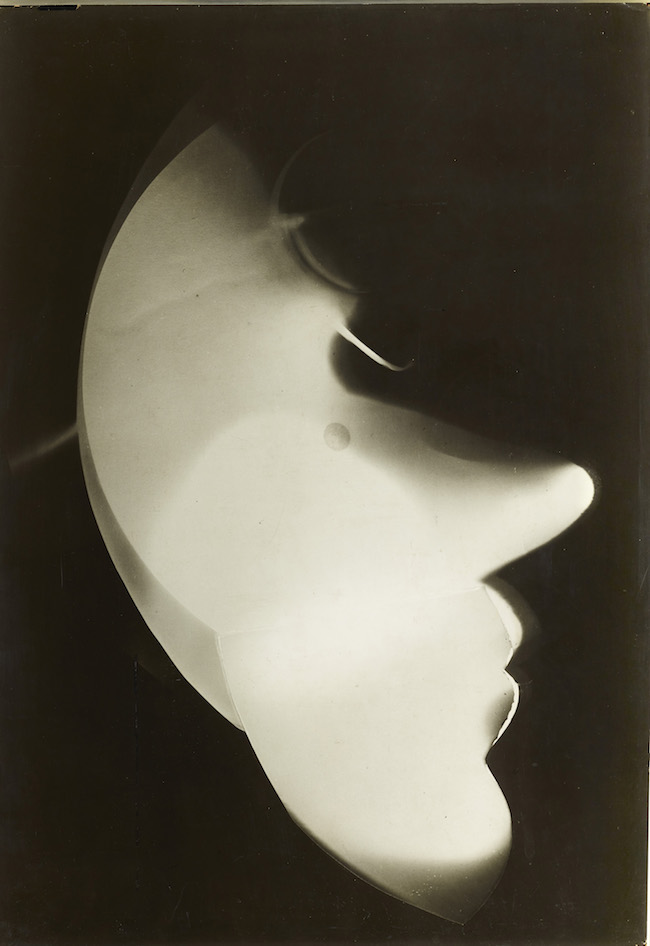

Nine years ago Daniel Hug left Los Angeles for Germany, where he became the director of the Art Cologne art fair. Although his home is in Cologne now, Berlin is also an important city to him, not only because of recent business developments (September saw the premier of the Art Berlin art fair, a co-production of Art Cologne and Art Berlin Contemporary ABC), but also due to personal ties. Berlin is where his grandfather, László Moholy-Nagy – the legendary Hungarian artist, theoretician and one of the founders of the Bauhaus school – spent his most productive years, and it is where Hug’s mother was born. ‘I have a closer, more familiar connection to Berlin,’ he says. ‘Moholy-Nagy identified himself as a Berliner.’ Hug kept quiet about his influential ancestry for years, pulling it out as a trump card only when he had to prove that he knew his way around modernist art when applying for the job of director of Art Cologne. Now he has become a real patriot of the German art scene as he emphasises the regional focus and local orientation of Art Cologne. Becoming a global phenomenon is not on the schedule, Hug says, explaining: ‘The idea of an international movement was really born in the 19th century, and partly influenced by Marxism – the idea of creating a new world, a new vision, and a new way of living and dealing with technology and politics. It worked. It worked because it was a tiny little group of bohemians doing it. It was interesting because it was a small group. If the entire world is doing it, it's a disaster.’

László Moholy-Nagy. Photogram Mondgesicht (Moonface) or Self-Portrait in Profile, 1926. Gelatin silver photogram (enlargement), 97 x 68 cm. © Moholy-Nagy Foundation

Why did you decide to become an art fair director nine years ago?

This is a funny thing. I felt that there were too many galleries and too few art fairs at the time. I mean, relevant art fairs.

But the story begins with the moment that I moved my gallery to LA. I had thought that there we would be, maybe, five or six galleries of the same caliber, while, for instance, in New York, there were already fifty galleries at this level, and there we’d just be number fifty-one. So our first thought was ‘Wow! Let’s move to LA, where there are only five other galleries to compete with! There we’ll be number six, while in NYC we’d be number fifty-one.’ Of course, we didn’t realise at the time that New York has 200 collectors, while LA only had about seven.

One year later we closed. It was a disaster. After a few years, I reopened the gallery and applied to Frieze in London, which was a kind of cool fair back then. And I was rejected. I remember my confusion...I knew everyone on the committee – there were six people, five of whom showed artists that I had worked with when I had my previous gallery. ‘Why did you guys reject me? We know each other.’ I remember I sent them an email: ‘Hello, what's going on?’ They answered that they knew what I did back then, but now I have a new gallery and a different programme. And that’s the problem with the art world – if you step out of it for even a moment, it’s very hard to get back in. Then I started to think – maybe I could start a fair in Los Angeles? It's much cooler than London. Who cares about London? Grey, horrible weather. And there was a terrible regional fair in LA, in which I had decided to participate. It was quite interesting when all of the collectors who showed up asked me – What are you doing here? And I asked them back – What are you doing here?

So then I told the owner of the fair – look, we could make a really great fair. The year after, I recruited all of the galleries; we did it only with LA galleries. Within a month I had figured out that it doesn't make sense to bring international galleries because LA is like Berlin. It's huge and so many of the galleries are sprawled throughout – from Santa Monica along the ocean to Hollywood and all the way downtown to Chinatown – a hundred galleries, from very young ones to very established ones. The idea of doing a fair with just these galleries simply made a lot of sense. And it went really well. Works were sold, people were happy.

On the last day I went to a bar (after the fair I was quite happy since I had sold very well). There I found that the director of Art Cologne had been relieved of his duties. I went home and thought about it. Two hours later, I sent an email: ‘I would like to apply for this job’. They called me and said: ‘You have great experience working with contemporary art, but what about classic modern art, what about modernism? We have a lot of modernist exhibitors at Art Cologne.’ I replied: ‘Well, my grandfather was László Moholy-Nagy.’ It was the first time I had used that bit of information; people didn't really know. I didn't tell anyone who my grandfather was.

Gagosian Gallery, Hall 11.2. © Koelnmesse GmbH, Harald Fleissner

Did the fact that your grandfather was one of the leading figures of the 20th-century avant-garde influence your relationship to art, your views on art? And if so, how?

It definitely did. In the beginning, it had a huge influence. In my childhood, my parents would take me along to galleries and museums. I remember going to gallery openings as a very young child. When I went to art school and was thinking of becoming an artist myself, it [my grandfather’s fame] became something I wanted to bury. I didn't want to be associated with this sort of legacy of modernism and Bauhaus. This was in the late 80s, early 90s in Chicago. The schools had a really postmodern programme...with a focus on gender politics, on issues of race. It was a very different focus compared to the classic modernist approach. After art school, together with Michael Hall I opened my first gallery in Chicago – Chicago Project Room. And there we became obsessed with appropriation and neo-conceptual art, which was seemingly far away from the ideology of classical modernism and Bauhaus. And it's only been recently that I’ve seen, particularly in my grandfather’s work, approaches to conceptual art. He is something of a missing link between 60s conceptual art and modernism from the first half of the 20th century. So, yes, it's been a huge influence. I think that only more recently I’ve been able to deal with it more. I mean, I kept it really secret while running my gallery.

Laurent Godin Gallery, Hall 11.2. © Koelnmesse GmbH, Harald Fleissner

You once you said that the focus of Art Cologne is progressive art. Could you give me a definition for, or a characteristic of, progressive art?

When Rudolf Zwirner and Hein Stünke started Art Cologne, in order to build an art fair and rent a building from the city, they had to start-up a non-profit organisation. So they founded the Association of Progressive German Art Dealers. I liked that, for one. I like the idea of art being progressive. I think it's the intention behind modernism and also conceptual art and contemporary art practices. Progressive art is a nice, general term. I think it's a departure from academia, from the traditional moods of art making – landscape painting, portrait painting – and really aims for something higher. So, it made sense to me (especially after arriving at Art Cologne) to go back to the roots – to 1967 and this approach. I mean, one fascinating thing is that, in the first edition of Kunstmarkt Köln, which is what Art Cologne is usually called, there were 18 galleries, and only three or four of them specialised in art that could be characterised as ‘old art’ or early 20th-century modern art. And that all took place in 1967, only twenty-two years after World War II, and, taking into account the fact that between 1937 and 1945, not too much happened in the art world because of World War II! If we look at it from today’s perspective, go back 22 years and you are in 1995.

Which seems like only yesterday...

Yes, it's not even the 80s. But how much has changed over the last 22 years! Using the example of my grandfather, you can understand how important it is for art to be able to adjust to a new way of living. Moholy-Nagy saw this as a sort of critical point for mankind in which it had to get used to a new world being run with machines, a world in which airplanes had suddenly appeared. He grew up in a small village, but he saw the first automobile, then the first airplane, then electricity, telegraph lines, the telephone... These were huge steps. And I think that in the last twenty years, we’ve also taken huge and enormous steps. Mostly in terms of the internet, and virtual reality. I think there is something very similar going on.

László Moholy-Nagy. CH 7 or Chicago Space 7, 1941. Oil and graphite on canvas, 120 x 120 cm. © Moholy-Nagy Foundation

But does the form of expression being used have any relationship to progress? For instance, you mentioned painting. Does painting, as a manifestation, have the ability to be progressive?

Of course. It's funny but, you know, Moholy-Nagy declared painting dead. I think he did that in 1930. And in 1935, he started painting again. He just couldn't get away from it. There is a nice letter he wrote which was printed in Telehor, a Czech magazine published just once, in 1936. In the letter he wrote that, for the time being, we have to continue with easel painting because there is no other means of painting. A lot of art historians like to speculate that Moholy had a really huge impact on internet art. Possibly, but I still think that he was a painter. Painting… is… art. It's a kind of abstract thing we call art. It's most easily identified as art. You hang a painting on the wall in a museum, and people understand that it's art.

But how can one distinguish good art from bad art, and progressive art from non-progressive art?

Oh, yes... I think that good art reflects our life today more sacredly, and it's something that develops over time. I think that looking back 20 years, even looking back at the art made in the 1980s, there are works that, for a time, played a hugely important role. But today, many of them are kind of meaningless. Time has done its work, and today we look at this art from a completely different viewpoint.

Could you name some examples of this?

Perhaps Julian Schnabel, who was one of the leading artists in the 1980s...

I like him very much...

Yes, he is a good painter, very postmodern. But I think his role in art history will surely diminish in the coming years. Or David Salle – yes, he is the best example! He was the most expensive artist of his time; in 1987, I think Mary Boon was selling his paintings for a million. You can buy him today for 60 thousand. His value fell. That’s not to say he won't have a revival. There's a good chance that David Salle could see a revival. But never of the kind that he had in the 80s. In the cultural space, fashion, and music of that time, David Salle fits rather perfectly.

Hall view, Hall 11.2. © Koelnmesse GmbH, Harald Fleissner

It seems that today, the art market and the art scene are more closely linked than even back in the 1980s, of which you just spoke. Perhaps even disturbingly close, to the point where art is thought of as an economic sphere and artworks are simply yet another consumer product.

The market is a difficult thing. Largely, it's misunderstood. You know this is me, personally, talking. You can buy a painting by Moholy-Nagy at auction for maybe 1.5 million. And there are contemporary artists like Mark Bradford – his paintings are selling for tens of millions. But you know, that's the market. The market doesn't make any sense. One is a museum artist who has made a true impact on how we think visually, and the other is just some sort of an art-market darling. Does this mean anything? I mean, in the 1950s, Bernard Buffet was bigger then Picasso. He bought a limousine before Picasso bought a limousine. Bernard Buffet was huge. He was a superstar. Twenty years before that, it was Raoul Dufy. Where are they now? I don’t think the art market should be taken so seriously. It's always been like this. People think that before today, the art market was never so huge and so global. But that’s not true! If you look at the French salons of the 19th century, they were huge. People came from all over to buy pastoral still-life paintings of cows and meadows. People from Germany, France, Italy – all of Europe would go to a French salon to buy something. And there is a tonne of the stuff, but it's all pretty much worthless today. You can find it on e-bay, you can find it in antique shops. Van Gogh sold one painting in his life; Kurt Schwitters couldn't sell his collages after World War II. Marlborough Gallery created a market for him. They were selling beautiful Kurt Schwitters collages for 500 dollars. We would never succeed in refining the art market into a smoothly running machine. It doesn't run smoothly. It's unpredictable.

I am very suspicious of a global art market machine. Everyone in the art world knows the schedule – you have Art Basel in the summer, you have spring auctions at Sotheby's and Christie’s in New York and London, then you have the autumn auctions at Sotheby's and Christie’s, and then you have Art Basel Miami Beach. You have these sort of events all over the world. Up until the 1960s, the Venice Biennale had a sales office in the back where you would go to buy the works that were on view at the show. Now when you go to the Venice Biennale, you see the gallerists of the artists represented in the pavilions. At least in the American and British pavilions, and so on. They offer their assistance right there.

Like a network.

They think so. But there’s nothing wrong with it; it's all fine. I just doubt that it works. It works for the short term, maybe. Long term…? The determining factors that will make an artist relevant or irrelevant in the future are determined through academic structures, through museums, through future generations, maybe. It's not something that we decide today.

Large-scale installation by Michael Riedel, Entrance Hall © Koelnmesse GmbH, Thomas Klerx

What about Art Cologne? What does it reflect?

Art Cologne focuses more on the regional market.

On the German market?

Yes. It's a relevant market. In Germany you have over 600 galleries, twenty of which are over fifty years old, with long traditions and countless artists, and which have played an important role going all the way back to the Middle Ages...

Art Cologne had a very intelligent background from its beginning – the progressive art statement that you mentioned before. Why didn't it become as fashionable as Art Basel?

Well, you have to look at it this way. There are two reasons. Number one is – there was an art market crash in the early 90s. That destroyed the art market for at least five years. And at the same time, in 1991, there was the reunification of Germany. And with that came the rise of Berlin. All of the focus went to Berlin and the new generation. Basically, the art market allowed a new generation of galleries to take the helm, to take the lead. And these galleries established themselves in Berlin. Cologne, at that time, was a very closed art scene ruled by a few power gallerists. Art Cologne was the leading art fair from it's founding in 1967 up until about 1997. So for thirty years it was more important then Basel, which is something a lot of people don't realize. Basel, prior to the mid-90s, was more of a dealers’ fair; it was more like TEFAF. It didn't really attract contemporary art. It was where very rich people went and bought Miró or Picasso or some other status symbols. Cologne lost its position because of the art market crash and Berlin, and apart from this, also because it had become too big. In 1967 they started with 18 galleries. In 1985 they had 165 exhibiting galleries, and in 1991 they already had 360 galleries. Art Cologne became very difficult to navigate. It was basically its own success that killed it. Now Basel has been very careful not to replicate that. They have chosen to go a different way, and that's by expanding into different parts of the world. First there was the founding of Miami Beach in 2001, then Art Basel Hong Kong in 2009. It presents itself as a global fair. If it is a global fair, why do they have a fair in China? Why do they have a fair in the USA? Americans know Art Basel Miami; they don't know Art Basel in Basel. We’re still basically dealing with a regional market. It's a nice idea and it's impressive to be able to say – We’re a global organisation!” But how global are you if you need two additional fairs to cover the market? It's impossible to have one fair that reflects the goings-on of an entire world art scene. There is no such thing. You know, this goes back to modernist ideology. The idea of an international movement was really born in the 19th century, and partly influenced by Marxism – the idea of creating a new world, a new vision, and a new way of living and dealing with technology and politics. It worked. It worked because it was a tiny little group of bohemians doing it. It was interesting because it was a small group. If the entire world is doing it, it's a disaster. Basel is creating this idea of a global monoculture of an art market. Not even visual culture, but an art market.

Choi & Lager Gallery, Hall 11.3. © Koelnmesse GmbH, Hanne Engwald

Yet isn’t Art Cologne also proud of having global blue-chip galleries?

Yes. You need the big brand names, of course. But how we differ from Art Basel is that we have a purpose. Basel is a pure market. Art Cologne was established to support the German galleries because there was a slump in the art market in the late 60s. And Hein Stünke and Rudolf Zwirner had an idea based on documenta – why not make a selling show, like documenta. And it worked like a charm. So, sticking to these roots is what's important to me. And it opens different possibilities.

I think what really fascinated me when I moved to Germany is that there were local galleries that played a very important role in Germany. But I didn't know about this when I was in the United States. There is a picture you have in your mind of a place, but then you go inside...

What did you see inside?

It all was very interesting to me, especially because Art Cologne had been such an important fair for so long. I had heard about these thirty galleries that were over 34 years old, and which had always been a part of the fair. Older galleries, like Galerie Utermann or the super-famous Galerie Hans Mayer or Galerie Thomas – there are a lot of them. Many of these galleries have been doing Art Cologne since 1967. It's so refreshing to talk to them, to get to know their thinking. You know, like, some years you sell nothing, but it's Ok because then you suddenly do sell. And it's really great! This is a different approach, and I think a more wise one and based on how things actually work in the art market. It was a challenge to bring these older men and women together with the new and young hot galleries. And to rediscover them.

One of the most exciting moments for me was getting Fred Jahn to do the fair again. Because he still is one of the most important gallerists in Munich. He was partners with Heiner Friedrich in the late 60s and early 70s; he was one of the key gallerists. He created the careers of Cy Twombly and numerous other artists. Fred Jahn stopped doing Art Basel, and he stopped doing Art Cologne in the 1980s, I believe. He just wasn't interested in art fairs. Insiders knew about him, but international art lovers had no idea who Fred Jahn is. I visited him and said: ‘Do Art Cologne!’; he answered – No. Then his son, Matthias Jahn, suddenly joined the business. And Matthias did want to do art fairs. So Fred said: ‘Ok, let's do Art Cologne.’ It went really well for them; they sold well. This was fantastic! This is what, for me, defines Art Cologne apart from Art Basel. We have this obligation and role to support the German art market. Our approach is to bring in galleries that should be in the fair, galleries that have had a historical impact. That's a very different approach from the idea of wanting to be fashionable, wanting to have only the best galleries from each country in the world –basically being an Olympics of the art world. Because art cannot be classified as such. If you have the Olympics of the art world, it’s like having somebody in a wheelchair competing against a Nigerian sprinter, but they’re both playing basketball. It doesn't make sense. Art is too different. You can't have this kind of a competitive nature.

I think there is a prescribed idea of what an artist is: The Young Artist... What does that mean? Is it someone who is physically young? Or are they young and fresh in how they do their work? Sadly, that's not how the art world sees it. At least not the art market.

Beck & Eggeling International Fine Art, Hall 11.1. © Koelnmesse GmbH, Thomas Klerx

The world is obsessed with youth, and so it follows that with young artists as well.

Young galleries, too. When I opened my first gallery, suddenly we were embraced by the international art world. I made the mistake of thinking that they liked us because we were doing a good job.

But they liked us because we were young and we were new and we were a new flavour. It's like being a fashion model. After ten years your looks are gone, and you can forget it. It’s exactly the same with galleries. It's a pre-prescribed idea of what a young gallery is. And they show young artists. Like the Liste fair in Basel charges a premium for the booth if you show an artist who is over forty years old. But look at Louise Bourgeois. I think she was sixty when she was discovered. She was a young artist at sixty or fifty nine!

Art Cologne and Art Berlin Contemporary (ABC) have partnered to create a new art fair – Art Berlin. Are you not concerned that, although Berlin is a very energetic and spirited city, it is widely assumed that it does not have a concentration of big money?

The ‘no money’ thing is something I was prepared to face when I took over Art Cologne. It's really quite funny – back then people would say to me: ‘Mr. Hug, Art Cologne is dead! Everyone is in Berlin. Berlin is the new centre.’ And that is what happened – the gallerists went to Berlin, the artists went to Berlin, the curators went to Berlin. But the collectors didn't. They stayed where they lived, where their jobs were, where their factories are located, and so forth. And that is why Art Cologne is still important. This is what I said nine years ago. Is it still true? I don't know. The art world is small, it's tiny. I like to say that the market for mattresses is much bigger than the market for art. Everyone needs a mattress, but nobody needs art. If you have three or four collectors in a city, that's a huge amount. I remember when I had the gallery, I worked with a collector who would only the buy the works of one artist, but that allowed me to make a living. And I could show many other artists as a result. It was last autumn, during Sotheby's modern auction when Klimt's painting was sold for 48 million pounds. That sale made the auction go from being an absolute disaster to becoming a huge success. One Chinese collector changed the direction. That's the problem of the art world. It's too small. If there are three people who buy art from different galleries in Cologne, that makes it a centre of collecting.

Does this mean that in Berlin you also need three collectors?

Kind of. If they are really active and buy a lot. It's all that you need. In the meantime, there are a lot of collectors in Berlin. With my first gallery, I participated in the Art Forum Berlin fair in 1998, 1999 and 2000. And we sold well. It was a great fair. But is it true that Berlin is sexy but poor, and is the Rhineland full of money, full of wealthy industrials who buy art? I think there are collectors all over Germany. Some live in small towns and they travel. And if we do a fair in Berlin, they come to Berlin. And if we do a fair in Cologne, they come to Cologne. I know a few of the big Cologne collectors, but it's nothing extraordinary that doesn't exist in Berlin as well.

Portrait of László Moholy-Nagy on the streets of Berlin, 1933. © Moholy-Nagy Foundation

I also know Berlin collectors. There are different reasons for why we are doing Art Berlin and why I am stepping-in in Berlin. For one – my mother was born in Berlin and I have a closer, more familiar connection to Berlin. Moholy-Nagy’s best years as an artist were spent in Berlin. He identified himself as a Berliner. At that moment in time, Berlin was really a leading city of the avant-garde. The Weimar Republic years. So this is the reason why Berlin is interesting to me, personally. However, in terms of the fair, there’s a much more salient reason, and that’s linked to the processes going on in Berlin, with the closing down of Art Forum Berlin and the birth of the new and experimental ABC fair. I think it’s a fantastic platform which, by working together, we can make workable and sustainable. I think Berlin still has huge potential. There are so many international artists and there are a lot of international galleries active in Berlin. Doing a fair in Berlin makes sense. Berlin and Cologne are in no way competing with one another – the first takes place in the spring, the second in autumn. And besides, as I said before, Cologne is this really ancient, traditional model of an art fair. I spent the last nine years bringing Art Cologne back to what it used to be. Back to its original focus. Back to this sort of national idea of an art fair. With Berlin, we want to totally experiment and take it in a new direction. Both of the fairs will be focused on their own uniqueness.

Daniel Hug. Photo: Gene Glover, Berlin