There is everything, and there is nothing

A conversation with Romāns Korovins, shortlisted for the Purvītis Prize 2019

08/04/2019

Romāns Korovins graduated from the Graphic Art Department of the Art Academy of Latvia in 1997, and yet came into his own as an abstract expressionist painter. As a result of a predictable contingency of circumstances, however, he started to earn his living as a director of TV commercials and musical videos. In 2000 he moved to New York, where he worked as a manager of one of the weirdest art galleries existing in the city at the time. When he returned to Latvia, he continued his work in advertising. Alongside that, never giving up painting, he gradually started creating his trademark Romano-Korovinian pieces. These are basically always very simple things – static (in case of photographs) or moving (video) pictures with half-mocking, half-ironic captions/titles. A bit absurd, a bit surreal, they somehow wonderfully and entertainingly help us recover our sense of reality: the reality of life outside the window, the reality of life around the corner, behind the nearest turn of the road – of completely pomposity-free and self-sufficient reality. With equal ease, Korovin interchanges or questions the concepts of ‘the sublime’ and ‘the base’, the big and the small, the distant and the close. All with a goal of (expressing it through the words of curator Viktor Misiano) ‘detecting contradictions and gaps in the structure of the world, win back some short yet intoxicating and therefore indecent moments of freedom’. In 2015 he contributed to the group project Ornamentalism. Purvītis Prize. Latvian Contemporary Art as part of the collateral event programme of the 56th Venice Biennale. In 2016 he was exhibited at the Extension.lv group show hosted by the influential Triumph Gallery in Moscow. In 2018 his works were represented at the Achtung – Mind the Gap: The Rohkunstbau XXIV Project exhibition in Germany, and a solo exhibition awaits him in Helsinki in 2020. In recent years Korovins has successfully started to combine his ironic photos with paintings, in many ways very much akin to them with the mundane subject matters, visual humbleness and a sort of philosophical ‘gaggism’. And his Satori of Master Wu and Master Lee exhibition (which ran in Arsenāls exhibition hall’s Creative Workshop a year ago and was selected as one of eight candidates for the Purvītis Prize 2019) saw the artist combine these two media again, adding to them video and objects. The result was a full-fledged and substantial statement about two ‘masters’, two beings who, to the best of their modest or immodest abilities, strive to attain enlightenment or whatever they understand by the word – attempting, of course, to forgo any words or concepts, at least temporarily.

Romāns Korovins. Master Wu and Master Lee childhood. 2016

We could structure our conversation as a sort of reconstruction of the exhibition…

There was actually a reasonably articulate story behind it all. The format of a historical material on two Zen masters – non-existent, imaginary ones, who were progressing along the path of their practice. And then there were their own teachers, mysterious friends and examples of meditation. Everything in pictures. And the result of their practice was also presented: one of them became enlightened, the other one – not so much; it didn’t quite work out for him. And then he took up painting. So there were his purported paintings hanging on the wall. It could, in fact, be considered a documentation of their lives, their life story in pictures.

Where did these names come form – Master Wu and Master Lee?

I just made them up. There was a Master Bo, after all (in one of the early songs by Boris Grebenshchikov and Akvarium band – Ed.). It is all very Taoish, very Chinesey, and yet, as it becomes clear at the exhibition, it can perfectly well be quite Latvian, too, quite local.

Romāns Korovins. First meditation. 2016

Have you read a lot of that sort of literature – the life stories of wise men and sages?

Yes, and I like them very much. Not that a lot of that ever sticks in my mind; it’s just that it somehow tunes me to a very pleasant frequency or something. And I find it calming. I have stumbled across many a little book with an orange Buddhist cover. So I read them, and read them, and then I made this exhibition.

A review said that it was a deliberate mystical fake.

Who am I to hold forth about enlightenment, satori and that sort of stuff? I presume that it is possible to see the world from a completely different angle and outside of any conceptual thinking. I can imagine that. But personally I have never had an experience of that sort.

Romāns Korovins. Roots Woman. 2016

Then you are yourself closer to the other master, the one who eventually took up painting?

I am the same as everybody. We sometimes think that we are on some sort of a sublime plane and sometimes – that we are base. Also, our time, the time of our life, it’s so... long. Probably, at this point, yes, I am closer to him. But then again, it is not a once-in-a-lifetime thing; I could knock at the gate later again. Which means that we shouldn’t call it while we are not dead yet. We can think about it and practice something to the very end. Better practice than think.

Do you practice anything?

Of course, I am an artist. It is in itself quite a good practice. The choice of colours, the combinations... Generally, there is this moment, right now, when we are what we are. We are sitting here, and we are right in this very moment and on this spot. If we wander off in our thoughts, we start to define everything that is around us. Look, that is Sergejs Timofejevs sitting there, and he has this sweater on. These are books; who has published them? Why have they published them? But we can also look at it all without naming things. I’m not saying – abandoning thoughts completely, but sort of stepping away from the flow of thoughts. You can simply be in the moment. Feel the presence outside the concept of ideas and names.

Photo: Andris Zieds

There is a certain shifted temporality in your works, your diptychs. One image, another image, and they are both very close. A binarity. But in the second picture, there is an additional plane of another time or an imprint of yet another space. Together, they constitute a now that is also a tomorrow and a day before yesterday.

That is exactly the sort of presence where there seems to be no time: you are right here all the time. A slight timelessness. Or you could say that, when the ‘before’ and the ‘after’ overlap, a different time is formed, a consolidated one. (Pauses, then reaches for the catalogue of his exhibition on the table.) Wait, let me see what I am talking about here. (Both laugh.)

You have been doing this kind of thing for quite some time in photography, but for a couple of years now this kind of binarity has been present in your paintings as well.

Yes, there is also a story here with a beginning and an end. A super short one. Just the beginning and the end. The middle is an emptiness or a pause. I find it interesting that you can create a story like this, one that doesn’t have a particular meaning. You cannot explain verbally what it was all about. There is snow here and white paint there... So what about it? In painting, there emerges a certain plastic correlation between these two white colours, and it carries a content of its own; it takes us to a point of emptiness, of ‘non-conceptualization’. There is no literary narrative there. Nothing to tell. A scoop net and a hedgehog. The scoop net covered the hedgehog. For me, there is everything in this, and there is nothing. Nothing really happened, and everything happened. There is a moment of pause. What makes art important? A pause, an emptiness filled with a content that you cannot really define using words. A sort of ‘Fuuuck... Well, I say!’ And there are different levels at that; you can look at it one way and another, and yet another... And, no matter what your angle, your vantage point is, it’s still awesome.

Photo: Krišjānis Piliņš

Photo: Andris Zieds

Symbolism?

No, not symbolism. Perhaps if there was just this pure white screen in the beginning, which eventually overgrew with bushes, then you could say that it was symbolism. This is more about a movement: there was this pothole in the tarmac, and someone had put little flowers in the hole. If you describe it with words, it’s just silly, whereas in painting the result is good, and it speaks to us about things that are best not described with words. A yellow flower is covered with a blue bucket. What happened there? A drama of some kind. You can analyse it, but it doesn’t work very well. It would probably work better in music or in a poem.

A young artist who wrote about your exhibition added to the review a few of her own haikus.

Cool, now that’s something!

Have you read them? (Hands a printout.)

No... (Reads.) ‘Snow-covered road. / Two pairs of trousers / Talk about life.’* Excellent! Yes... Although I was thinking that, when you walk, you represent the part of yourself that is the most important one at the moment – your legs.

Romāns Korovins. Walking legs. 2011

Many interpret this picture as a mysterious disappearance.

The farther these two go, the more they fade. In the beginning they are complete, in the middle – just the legs have remained, and by the end no more than their shadows have been left over. And then there is nothing. Lovely! (Laughs.) And everything in white...

Alongside your photographs and paintings, you were also showing an object at your exhibition...

Yes, I thought that we did not actually know what this great enlightenment looked like. What is it that a person sees when he or she has reached satori. In this case, it is a sort of energetic explosion, an emergence from a 2D photograph into an object. There was also a door; I managed to use it in an excellent way, as if the person had walked through a ‘window’. There is this continuous pulse on the wall created by a single repeated photograph with blossoms of fireweed – like a line, and then the same photograph, but as a giant blossom or something like that constructed of countless prints – something pink and fiery, a portal, a blow-up. As if he had walked out. And right next to it, for the other master: when the flowers wilted, nothing happened – zero. (Laughs.) It’s great to be able to find delight in serious matters – not make fun of them but just smile about some sort of important stuff. Because over-egged solemnity is even funnier.

Photo: Andris Zieds

There was also a video at the exhibition...

There is this empty room in the front, quite a dark one, and I thought that it would be nice for a video; and then you move on from this dark place into the world of the two masters, a light-filled one. So that the same subject is treated in video, photography, object art and painting. I like it when the same idea is depicted in all the media and formats. The actual film was not about the two masters; the subject was a winter meditation and also displacement. Fishers disappear on the frozen Daugava – now they’re here, now they’re gone. There is white ice all around, a white desert. A bit of wintry stuff and a bit of cold, because when you move on to the satori, it is all very southerly, very spring-like. But it is cold in the dark. Warmth and cold, seasons of the year – all sorts of things are connected with that here in Latvia. Seasons are the most real of all things around us, the most active. The rest of it... politics and stuff... that’s all adopted from somewhere else, that’s borrowed...

A construct.

Nature dominates here.

Perhaps that is why, while there are all sorts of conflicts, nature seems to smooth things out. We never quite reach the boiling point.

Well, yes, things are heating up, but then it’s the Midsummer Night, and we all forget who is from which political party...

In your works, objects from ‘civilisation’ appear amidst this nature all the time, and they fit in the picture perfectly, never looking out of place in the landscape.

Better, they play the key role there.

A shopping bag from the Rimi supermarket...

You say it’s a Rimi bag; I see it as a red spot that moved from the lawn to the graffiti and kept shifting around until it ended up as a red cap on a swimmer that seems to be standing on the edge of a precipice. Very dramatic. I use everything that I see – monuments, graffiti on the wall...

What I mean is that there is an integrity of the world; there is no division into nature and civilisation.

No, no, it is all one. Everything is together. Also, civilisation, of course – such a word...

Fine, let’s say – nature and man, all sorts of man-made objects.

Perhaps so... A crumpled-up paper that looks like a rose and pretends to be one in the middle of a rose bush – it sort of fits size- and colour-wise, and yet it is not a rose, of course.

‘Pretends’ is the key word here. Pretence as an element of play.

There is someone who wants to be something else. Someone small wants to be bigger, or someone strong wants to be even stronger. It is dissatisfaction with who you are; it is like that for every human being. We all want something more... We all play some kind of roles, and it is quite funny when something small wants to be big. The contrast serves the purposes of introducing the protagonists, the characters. I didn’t do that before. This is how they look, this is what happens to them. And these are not just portraits; it is all action, movement. They are surrounded by all sorts of mystic creatures, and the whole thing happens here in Riga, in the heart of the city.

Photo: Andris Zieds

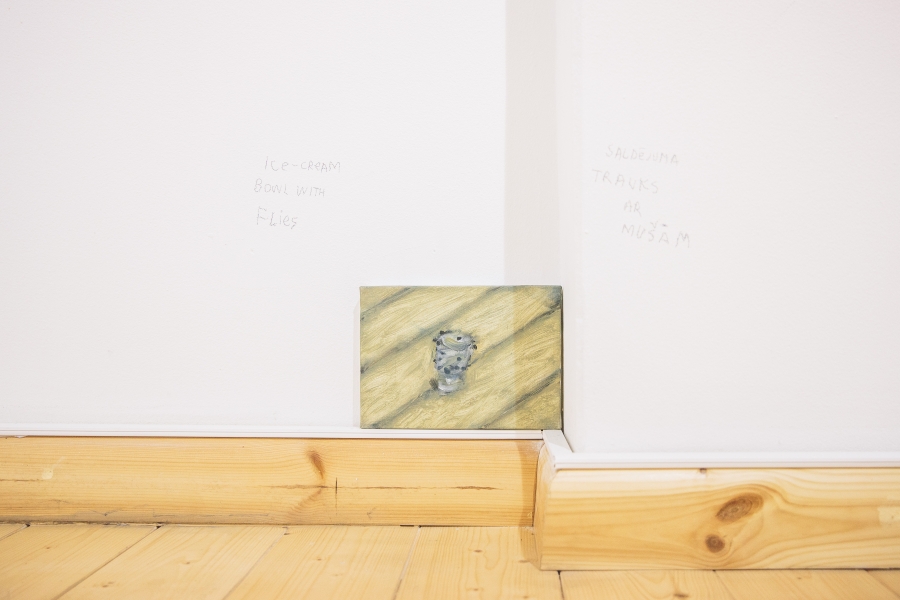

The final of the Purvītis Prize competition – it is definitely a sign of certain recognition and also an official confirmation of the fact that there exists an artist named Romāns Korovins with a distinctive style of his own. For instance, the titles of the works at your exhibition frequently appear as a pencil or ink inscription directly on the wall...

I tried other ways but found out that I actively disliked them. I find that these captions do not get in the way, and it is nice that you can just look at the picture or read the text, which almost like an ordinary wall, but there is nevertheless something written there. And there is no white square with printed words on it. It fits in so much more organically. I would even go as far as eliminate any sort of ‘art’ from the whole thing, in the sense of artificiality. There is this format in photography, 21 x 15. It is like the A4 format for a sheet of paper; everybody knows it and no-one even notices it anymore. (Picks up a sheet of paper from the table.) It has already become almost... disgusting. Everybody uses it; it is the standard. And I do, in fact, love these standard formats.

Which are so jam-packed that they have in fact become empty...

Yes, and so people wouldn’t say afterwards: ‘What an interesting play on formats – it’s smaller here and larger there!’ Here, there is nothing of the sort – at all. This is a cliché. As for the content: this stuff was standing upright in this picture; in this one, it is already lying on the ground; you can print it any old way, black-and-white or green – it does not alter the content in any way. It is like a logotype for which the most democratic, the most clichéd format is chosen. Everybody has some photographs which they simply stick on the wall with a double-sided tape. ‘Look, that’s just the way I hang them on the wall at home!’

Photo: Andris Zieds

Except the captions normally aren’t written directly on the wall at home.

It is necessary to make the photograph merge with the wall, to fuse the two together. With the caption written like that, it blends in even more. For the time being, I am keeping these captions... Although I did have a couple of exhibitions without any captions at all... Oh no, I didn’t! (Laughs.) It’s just that when it was not the usual white walls but the open brickwork of factory walls, what was needed there was not a pencil, which would have been invisible, but charcoal instead. But yes, it is the merging of the background surface and the work. It’s just like a song and a video; the video can enhance the song but it can also kill it. And everybody will remember the cool video, but what the actual song was – who knows. ‘Some kind of band or another.’

What is your situation with art collectors? Do your works ever end up in private collections?

It is, of course, nice to give away or sell something, because works do accumulate. It would be excellent if there were a small opening through which they would trickle away. There is no seepage as yet, and I am not going to make a special effort to make it happen. What I need is someone who would deal with that professionally. Although, two magic fairies from the LNMA visited me recently and bought 13 of my photographs... just to have some around. A proper Christmas miracle, that was. (Laughs.) And the curator of the German contemporary art exhibition at Arsenāls Mark Gisbourne also bought a couple. So there is, in fact, some trickling away happening occasionally...

Do you work with a gallery of any sort?

No… Generally, as far as money is concerned, it seems that God has been protecting me so far. Perhaps I’m not ready yet, perhaps I would lose the plot completely. As long as I get to draw… Money is a separate matter. In New York, if you make a couple of solo exhibitions and get a good press, you immediately start to go uphill, up, up. We don’t have that kind of market. It is silly to pretend that you are on a beach in Miami when you are actually in a wintry forest – to strip down to your swimming trunks and invite people to throw a ball around. You are in a forest and this is perfect for you. You’ve got everything – the mysterious Latvian land, the hills, and the sun, everything. Walk around drawing, photographing, doing whatever you can do while you have this opportunity. When somebody appears who wants to buy stuff from you, they will find you – they will call you. (Both laugh.) If it is about money, they will call you. They won’t neglect to call you.

* By Lote Vilma Vītiņa.