Photography prevents alienation

An interview with curator Anna Kedziora

07/05/2019

The (Un)Natural Bodies exhibition, which is a part of the Riga Photography Biennial - NEXT 2019 and is on show at the Latvian Museum of Photography until May 12, focuses on the concepts of naturalness and unnaturalness in relation to the human body and various representations thereof. The exhibition is special in that the majority of the young Polish artists whose work is included in it are from a single school, namely, the University of the Arts in Poznan. The exhibition’s curator, Anna Kedziora (1982), is a teacher in the photography department at this school, meaning that she has worked with most of these artists for already quite some time.

For the past six years, Kedziora has combined these two professions, and her list of curated events includes, for example, the 2014 Photokina Academy in Cologne, the 9th Poznan Photography Biennale in 2015 and the European Month of Photography in Berlin in 2016. In addition, Kedziora is an artist herself. Her work examines the specific nature of photography as a language and its relationship to memory, reality, landscape and also the distinction between the natural and the artificial.

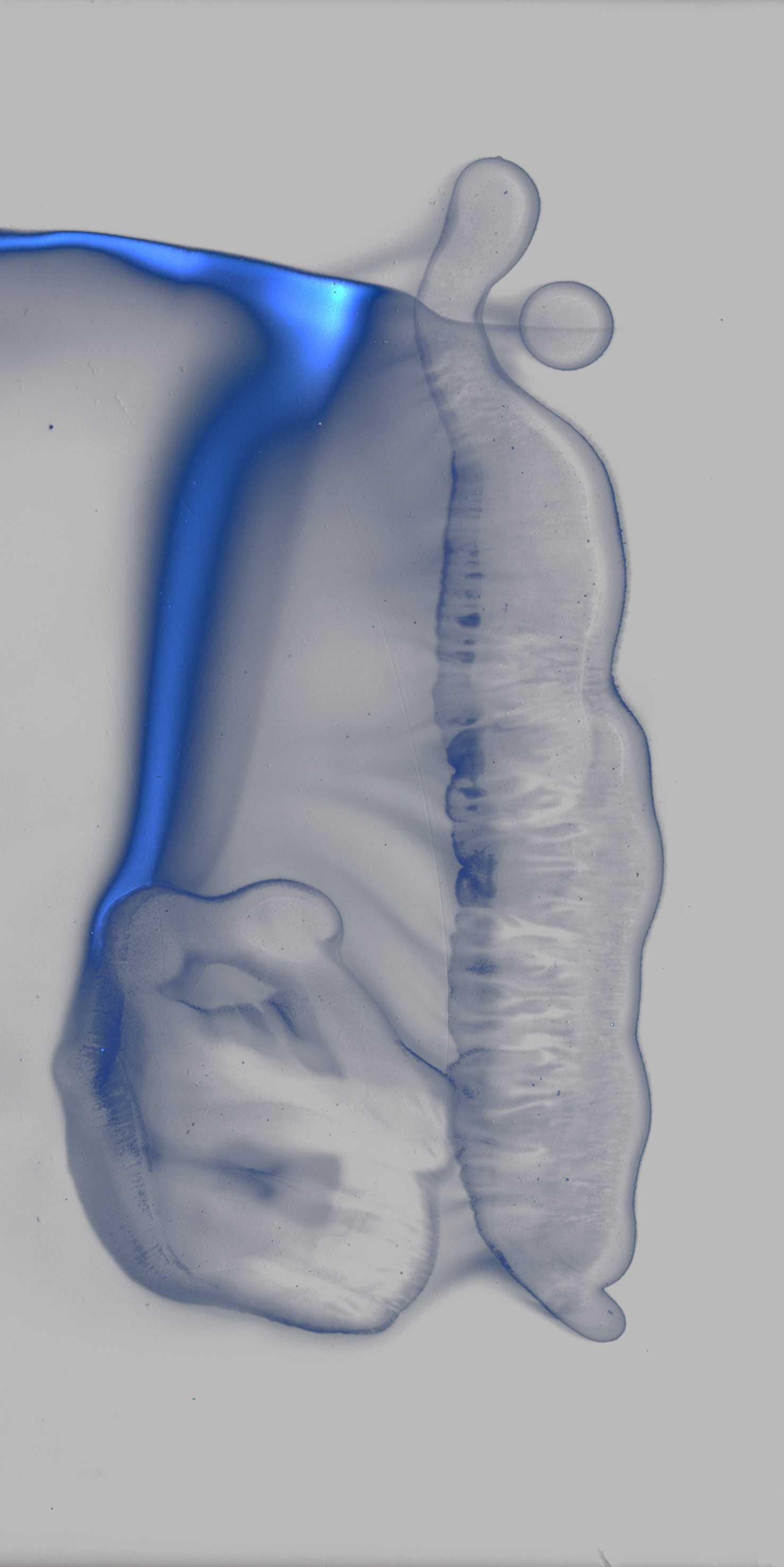

Agnieszka Hinc, from the series UX, 2018

Arterritory: The name of the exhibition you’ve curated at the Latvian Museum of Photography refers to the categories of naturalness and unnaturalness. Was your choice of this focus based on your own thoughts regarding the restrictive nature of the concept of ‘naturalness’?

Anna Kedziora: The idea was to examine the concept of the ‘natural’ in many different contexts – what exactly is the content of this idea about the opposites of the natural and unnatural, for example, from the perspective of the future, when the boundary between both of these will blur even more. But in general, the three most important elements of this exhibition are, first of all, the natural and unnatural; second, the body as an object of photography; and third, both of these aspects in the cross-section of time. What is considered naturally human right now might be in opposition to what will be considered naturally human in the future. For example, the issue of whether in the future we’ll even need a body – a body that we nowadays regard as natural.

The exhibition was created, first of all, by the motivation to examine this distinction between the natural and unnatural and, secondly, to examine the definition of the body – how to expand it, how to look at it differently in different contexts and at different times. Because I’m interested in landscape in my own work as an artist, I see quite well how fine and sometimes indefinite this line is between nature and culture. And increasingly it seems to me that what has long been considered nature is in fact the result of culture. I’ve gradually arrived at this concept both through my own work and through what I see students at Poznan’s University of the Arts working on.

Maybe you can give an example of a thing that is convincingly considered natural although it is in reality very much influenced by culture?

The first thing that comes to mind is, of course, the distinction between landscape and nature, in which landscape is understood as something that has been worked culturally, while nature is something supposedly untouched. But, if we stick to a purist definition like this, we quickly come to the realisation that we can’t consider anything to be ‘pure’ nature, because even the identification of something as supposedly untouched and its distinction from something else is an act of culture. Keeping this in mind, it’s interesting to then look at the human body and unusual perspectives about what a body can be.

And, as I already said, many students in Poznan are working with similar themes. The many interesting connections I saw between them helped me to create this project. In the end, it’s more than just a simple group exhibition – the participants have collaborated a lot while making it, and they kept discovering more and more new connections. There’s a very dynamic and dialogue-like process taking place between us, which is continuing. And as I watch that happen, I often think about how I’m seeing a good example of how work at arts universities should take place.

So, there are no real boundaries between the natural and ‘cultural’, or ‘cultivated’.

We’d have to look at the context in which we’re talking about it. But mostly, in general, I’d say no, there is no boundary, or it has blurred to such an extent that it no longer bears any meaning.

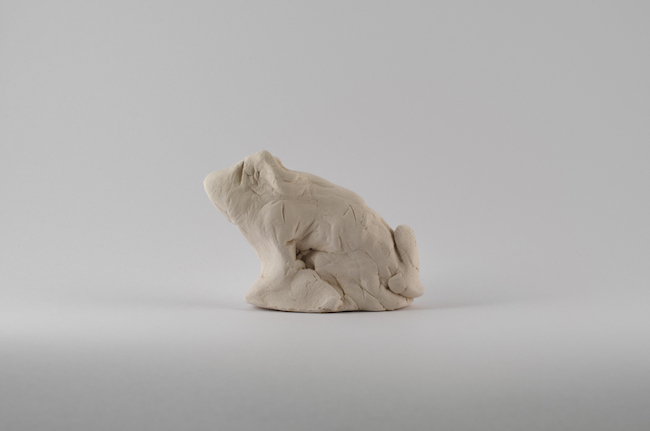

Katarzyna Bojko-Szymczewska, from the series Communicans, 2016

And yet, these are significant categories in which people think. Regarding the progress of art, do you think the existence of such categories is more likely to promote or hinder that progress?

I think it’s quite clear that it’s more likely to hinder the process. And that applies not only to the field of art. For example, our attitude towards the environment is determined by the extent to which we see ourselves as either a part of it or separate from it. Regarding art, the situation can be paradoxical, and there’s a lot of new art being made in Poland about this topic. You could say, for example, that the environmental crisis is in fact feeding the creation of art. It provides artists with many new perspectives to work with, but at the same time, they need to do this because other social groups have turned out to be powerless in solving this problem. So artists have to do it. The tension in art right now about how natural or unnatural we ourselves and our actions are is very palpable, at least in Poland. So, my answer to this question is nevertheless rather ambiguous.

How did you become interested in this topic yourself?

At least in part, it came from my desire to step outside my regular sphere of work, which is linked with landscapes. Sometimes I noticed that I assumed too automatically that there’s a strict distinction between the natural and artificial, and therefore I passed up many interesting things. I see great potential in attempts to expand the definition of the body, and many of our students are very mature artists who are able to challenge existing ideas about the body and its representation. For me, it seemed interesting to be at this point somewhere in the middle between the themes of nature, landscape and body. It’s a fertile mixture of things that I’m interested in and things that young artists are interested in.

Piotr Zugaj, from the series Rediscovered

How does this project tie in with your experience as a curator up to this point?

This is something new for me, because my previous experience as a curator differed slightly from what is usually understood by that term. I mostly work with final projects by students, and so my personal link and engagement with the exhibited artwork is different from that of curators who simply select artists to invite for a project. That’s why this experience, when I can travel with all of the artists to a new place and observe how they interact and the new points of contact they discover both in their work and between themselves as they work together with this one concept, is extremely interesting for me. This exhibition shows the exceptional sensitivity of young artists towards serious social issues and problems as well as their ability to speak about them in an aesthetically refined way.

If you don’t mind answering a very general question – how is it that precisely photography became the medium for this exhibition, for this concept? As opposed to any other genre.

The works in this exhibition are closely linked with photography, but not all of them can be considered photography; also, many of the artists are not primarily photographers. They’re artists who use photography. And why? I believe it’s a medium with broad potential for artistic expression, but at the same time it’s also a medium that’s very suited to people who are still interested in the environment and the world around them. Photography is a medium for people who do not want to become alienated from the world.

I find photography’s relationship with reality to be very interesting – it’s not a direct relationship. Photography is no longer a credible medium; maybe it never has been, but it’s especially not a credible medium today. And still, no matter how subjective it might be, it nevertheless retains a link with reality, which is very special in comparison to other media. This complex and deep connection photography has with reality is what makes many people rely on photography as a medium in their art. Being an artist who uses photography usually means making use of the deep connection to reality that’s available to us in art yet at the same time preserving lots of room for subjective manoeuvring.

Magdalena Adrynowska, from the series The whole emptiness

The theme for this exhibition inevitably touches people whose bodily identity is at the centre of very political discussions nowadays. For example, transgender people, as seen in the work of Johanna Berg. Maybe you can say something about how aesthetic and socially responsible aims either coexist or conflict with each other in your practice?

Both as an artist and a curator, and also as an observer of art, I definitely highly value people who address socially significant issues and speak about them through their practice, although I do not believe this is a duty. I’m most interested in art that focuses on social issues but is not outright activism – art that has found a kind of balance between social and aesthetic demands. Here, I think Johanna Berg is a wonderful example. As a curator, I know that the exhibition I’ve developed touches on socially sensitive issues, and I feel responsible for the way in which they’re spoken about.

Perhaps you can name a few examples of how this responsibility manifests itself in specific decisions you’ve made regarding the exhibition?

It’s quite possible that I’ve made lots of decisions like this without even really realising it, because I’m used to concentrating on this kind of work and artists. It’s my “natural” inclination to work with this kind of artists. It’s the way in which I communicate with the world and with these artists. If it weren’t so, I probably would not feel so sure about my need to do this work.

Machnicka Magdalena, from the series In order to see