We can see her being seen

A conversation with Alise Tīfentāle, Līga Goldberga, Sophie Thun, and Zane Onckule at the exhibition “I Don’t Remember a Thing: Entering the Elusive Estate of ZDZ” at Kim? CAC.

For the exhibition “I Don’t Remember a Thing: Entering the Elusive Estate of ZDZ” currently up at Kim?, the art space has become something of a laboratory. One room of the show has been turned into a darkroom, where during the week the artist Sophie Thun is printing from negatives of the late artist Zenta Dzividzinska (1944-2011, also referred to as ZDZ). Dzividzinska was actively working in the 60s, but was struggling with the male-dominant photography scene in Soviet Latvia, making images that didn’t conform with the aesthetic expectations of the time. As her daughter, the art historian Alise Tīfentāle, notes, what Dzividzinska was making was not considered to be art photography: “There was no institutional framework or intellectual context in which a young woman from Riga could exhibit such images and expect to be understood.”

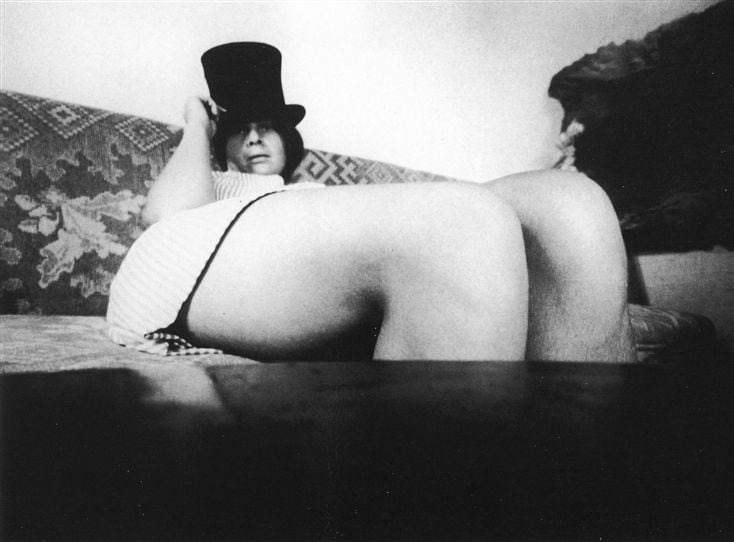

Zenta Dzividzinska, Self Portrait, 1968

Alise and curator Zane Onckule had talked about organising a show with Dzividzinska’s work for years. The idea for this exhibition came together when Zane saw Sophie’s work and recognised a certain similarity between the two artists. Part of the exhibition at Kim? consists of Sophie’s previous work and prints that ZDZ made during her lifetime, while the other part is the laboratory, which extends beyond the chemical processes in the darkroom. For the exhibition, Alise, the owner of the archive, has given Sophie and archivist Līga Goldberga permission to go through the cardboard boxes of this largely unseen material and use it to print images and to re-organise the negatives. More than an art show, “I Don’t Remember a Thing: Entering the Elusive Estate of ZDZ” is an experiment in how relationships between people, institutions, artists and their estates can work through mutual trust and curiosity while proposing new ways of looking at archival practices – thinking about preservation as something more than a physical act of keeping things in order, but also as a process of bringing to light that which has previously been boxed in.

Ieva: I wanted to start the conversation by acknowledging the sixth person, who is very present in the exhibition, but not here with us today. Everyone here has a different relationship to Zenta Dzividzinska, so maybe each person could share their first encounter with her?

Zane: Akin to the title of the project we have gathered here to talk about – “I Don’t Remember A Thing” – I have a tendency either to not remember, to remember badly, or to remember selectively. So at different times I may recall different things about the origin of this idea (laughs). One thing is certain – I remember having conversations with Alise about approaching Zenta’s archive and developing a project – either a posthumous solo exhibition or a duo project including Juris Tīfentāls’ (Zenta Dzividzinka’s husband and Alise’s father) works – already eight or so years ago.

To briefly comment on my personal history with Zenta – I had a chance to meet her a couple of times in passing. She was a graphic designer for “Fotokvartāls” when it was a printed magazine, and Alise was its chief editor at the time. I joined the team as the news editor, critic, and writer. I remember meeting her a couple of times at the “Neputns” office on Tērbatas street, so that was my professional encounter with her. Then, I think, Alise invited me to the opening of Zenta’s exhibition in 2005 at the LMS gallery, which was her second solo show. I felt really impacted by what I saw – large-scale black and white photos and, of course, the way that the seemingly ordinary if not mundane daily snapshots were composed. This encounter certainly added to my own understanding of photography, as at that time I was invested in it and regularly spent hours in the darkroom at the studio of Andrejs Grants. After that there was a break, but I kept in touch with Alise, and there was always an idea about trying to do something with Zenta’s archive and her legacy. We tried to approach museums for large and “proper” institutional shows locally and internationally, but right now I am pleased with what this lengthy preparatory work has culminated into.

Līga: I knew her work before the exhibition, but my knowledge was very scattered. I remember seeing her book in the library, and I remember seeing some of her works online. But it’s a completely different experience working in the exhibition because of the materiality and tactility of the archive. Online you don’t really get to feel the presence of the artist.

When working with an archive, one develops a relationship to the person. It’s important that Alise is always there to comment. We send her pictures, texts, and questions, and she always answers and gives us the necessary context. This relationship to the author is imagined, but Alise helps a lot in making our insights grounded in facts.

Sophie: I got to know Zenta Dzividzinska, or her artwork, through Zane, who contacted me over a year ago with an invitation for this show – an exhibition about Dzividzinska’s practice and mine. I remember being very impressed with how Zane, from a distance, not knowing me, put these two together and saw a kinship between us. When Zane sent me texts that Alise had written and PowerPoint presentations from talks, I also saw a relationship between the way that we both work, which is something that is difficult to put your finger on and verbalise. I see it amongst others in this “in-betweenness” of making art, and as a certain self-sufficiency; I think I read this in a text that Alise wrote – “the self-sufficient women” that Zenta was portraying. I see a kinship in this.

Alise: My relationship with Zenta Dzividzinska is the closest, but in a way also the most complicated. I have mentioned this previously, but when I was growing up in the 80s, I didn’t even know that she was a photographer. I have only a couple of pictures from my childhood and we don’t even have a proper family picture – photography was not around at all. Then in the 90s there was some interest from curators, such as Mark Allen Svede and Inga Šteimane, who were starting to research the history of photography in Latvia and what happened in the 60s. Somehow they found out that at that time there was this well-known, young and promising artist-photographer Zenta who did a lot of interesting work in the 60s, and then after that, disappeared from the scene.

Of course, later, in the early 2000s and 2010s, and especially in the last couple of years of Zenta’s life, I was helping her to scan some stuff and got an idea of what her archive might contain. But, of course, I have never looked at it as a professional would, so I also have no idea what’s actually in there. When Līga and Sophie find some negatives and I see the prints, it’s such a surprise because I had no idea that it existed.

What happens with the belongings of lesser-known artists or lesser-known photographers, with their archives and libraries? Everything depends on whether there is enough interest from relatives and family of the people who have passed away. While doing my own research on other Latvian photographers, I have seen many cases where archives are simply untraceable. For people who have passed away and there was no relative who saw value in this, most likely things were just thrown out. I always think this wouldn’t happen with painters because it’s more difficult to imagine that you just put paintings into the trash. People can’t just do that, but photography is always just papers or something, and there is no value in that.

That was the issue that we were talking a lot about with Zane, because after my mom passed away, I lived in the US and I had all her things just stored in a storage space. I couldn’t figure out how to make sense of this material, how to exhibit it, because most of these works were never printed in an exhibition size and format during the artist’s life. It’s kind of interesting – how do you exhibit something that doesn’t exist as an artwork yet and is just a negative? The way Zane connected Sophie and Līga together in this exhibition, it kind of answers all of these questions. This is the right way to approach a legacy like that.

“I Don’t Remember a Thing: Entering the Elusive Estate of ZDZ” at Kim? CAC. Exhibition view. Photo: Kristīne Madjare

Ieva: I also think it’s interesting that most people that I have spoken to, who have seen the exhibition, are very impressed and also very surprised that they’ve never heard of Zenta Dzividzinska. This seems both logical and shocking that there has been so little interest in female photographers and artists in the history of art in Latvia.

Alise: It’s not really shocking, it’s just the status quo of the research and how the history of photography in Latvia is treated. I think that there just hasn’t been a lot of interest in photography and especially in lesser-known artists who have been forgotten because they haven’t continued being in the public eye.

Zane: To add to what Alise said about photo-archives being less valuable in comparison to painting – if she wouldn’t be someone who is interested in art history, the chances that Zenta’s archive would have survived would be even less realistic. Throughout the years, Alise has numerous times used possibilities or invitations to communicate about Zenta’s practice. For example, by lending her works to Moderna Museet in Malmö for the group show “The Moderna Exhibition 2014 – Society Acts”, which was devoted to Baltic and Scandinavian artists. In this exhibition, a small selection of Zenta’s works were included to represent the artists from the 60s and 70s; talks and presentations about Zenta’s practice were also given. Thanks to all of that, Zenta’s presence, both locally and internationally, is already cemented via the boxes of archive material that have been saved and protected, as well as through the ongoing work to contextualise and interpret her work and archive.

Līga: You are both talking about negatives, and negatives don’t really have this immediate exhibition value as a painting or a print does. There are only so many prints that Zenta made, and then there are the digital copies that Alise has begun to make. So, there is this limited visual content that is accessible to the naked eye, but if you are working with negatives, and these boxes are full of them, you can’t really tell what is in there. It’s great that now you can take a picture on your phone and invert it, and then you can see what has been photographed. But it doesn’t have this accustomed exhibition value; how would visitors approach this little object? In this case, the body of the archive allows us to view it as a part of a whole – as an installation. It is important that these boxes are here and that all of these otherwise unseen processes, like printing and archiving, are revealed.

Sophie Thun, Reorganised (J&H), 2019

Ieva: When I was thinking about what we should talk about, I was thinking about archives in relation to which histories get to be preserved and which ones don’t. For example, a few years ago, the Getty museum in Los Angeles bought the entire archive of Harald Szeemann, the Swiss mega-curator. On the one hand, it’s one of the few institutions that can afford to buy and preserve it, but on the other hand, there were all of these questions of why is this Swiss curator’s archive being transported to the other side of the world, and maybe it should be the local histories of Los Angeles that should be archived instead.

Of course, there are fewer means in the geographical context that we find ourselves in, but there is still the question of what gets preserved and what doesn’t, and in that sense – what remains in history and what doesn’t.

Zane: I think that this is really the key question, a rather rhetorical one, of this exhibition. In one way, what was said about the negative being shelved, and then the phases and hierarchies of photography. What we have here starts with the slightly worn-out, barely over a dozen boxes housing the archive – precious material that hasn’t been touched for maybe 20 or 30 years; then the works from the museum collection and private collections by both artists; and then the large-scale labour-and-finances-consuming site-specific works by a contemporary artist made specially for this exhibition and that have a rather limited possibility of ever getting exhibited again unless the exhibition travels. For me, it is interesting to think about the ways how these separate works were acquired, what went into the decision to commission and produce these new individual pieces. Through the labour and the presence of the contemporary artist, I wanted to show the potential of how Zenta's archive could evolve or get re-introduced to the world in a new way, as well as to showcase the cross-generational dialogue born out of the absence of national, territorial and numerous other barriers, and the similarities and differences that have emerged.

“I Don’t Remember a Thing: Entering the Elusive Estate of ZDZ” at Kim? CAC. Exhibition view. Photo: Kristīne Madjare

Sophie: I think it’s also a choice or an effort to preserve things. I love this about the show – everyone was ok with us doing this. When Zane contacted me at first, it was about doing a two-person show; then she mentioned that there is this archive, and through Zane, I asked Alise’s permission to work with these negatives during the show, because Zane had seen my show at Secession. Alise agreed, which meant trusting someone she doesn’t know to work with these negatives. All of this is also possible because the negatives are in the state that they are in and don’t belong to an institution –because otherwise I can’t imagine anyone letting us work with them in the context of an exhibition.

Zane and I were doing Zoom calls every week and talking about finding someone who could archive the work – and then Zane found Līga. The exhibition was possible because of this team effort, of people agreeing to take risks, and also thanks to Kim? agreeing to this exhibition concept in which an artist tells them: Hey, I’ll just be here for two months, and I will just go in and out, and I will have your keys and turn your bathroom into a lab. I think it’s also something that isn’t so obvious – that an exhibition space lets you treat an exhibition as a genre, and that it continually changes every week.

Alise: It’s just magical that this is actually happening. And it’s so unusual for an exhibition to exist in such a format, especially for a photography exhibition. Here it is so different from what you’d expect from a photography exhibition in a museum or a gallery. But it makes so much sense considering the specificity of this archive and this person, and it is so personally moving – Zenta had, like, ten years when she was actively practicing photography, and later she had to devote her time to design work to earn an income for the family. Most of the things were left unsorted or unprinted because of a lack of time and resources. And now, ten years after her passing, there is time and there are resources, and there is actually someone who is looking at these negatives and working with them and printing new images from them – it’s beyond words.

Ieva: I like what you said about the fact that there aren’t a lot of original prints from the negatives, and that Sophie, you are making them in a way that you make prints, so there is none of this pretension to say that this is how Zenta would have done it; instead, it is an interpretation in a certain time and context.

Zane: I think the word “interpretation” is what we agreed upon, so we have this formulation for the work that is in the exhibition – these are photos by Zenta Dzividzinska, taken on a specific date and year, fifty or so years back, as interpreted by Sophie Thun in 2021.

Sophie: I took the term from music, because there is a work and then it gets interpreted.

Zane: Just to add, we almost have an entire female team – from the women in this conversation to the exhibition production led by Elīna Drāke and assisted by Elīna Kaire. We had great technicians-art handlers, who are men – led by Andris Maračkovskis, but other than that, I think this new gender proportion, in a way, counterbalances what Zenta experienced in the 60s and 70s.

Alise: What I remember from what she would say about the 60s was that she was part of this photo club that was the only institution where photography was explored, and how masculine it was – with just a couple of women in the middle of this very “manly” form of expression. As Zane says, now it has shifted and turned around.

Sophie: It’s nice how it’s a very multi-person show. That’s what’s super about it – it’s very much about multiplicity and allyship. Zane also used to work with Zenta Dzividzinska, so you also go way back, as does Alise. There are all of these kinships. And also thanks to Zane having a photographic practice herself, she sees and understands links and possibilities.

Ieva: Līga and Sophie, how do you work together on a daily basis?

Līga: We can’t be here at the same time.

Ieva: Yes, Līga, I thought what you told me before was really beautiful – in order to work, you need a light environment, whereas Sophie needs the dark.

Sophie: We have to meet for beer!

Līga: Yes, luckily, there’s also WhatsApp and we can keep in touch all the time. We share what we are doing and we are all amazed with what is in the archive. There are these Zenta’s prints that we already know and associate with her work and style. And then there are these new insights. For example, the first series that Sophie started to print is very important. She started with Zenta’s self-portraits – we can see her performing in front of the camera. We can see her gaze, we can see her being seen.

Sophie: It was because I wanted to create a very strong presence of Zenta in the space.

Līga: And you printed all of them.

Sophie: Yes, of course, none of us know – maybe Alise could guess – which of these works Zenta considered art and which ones not, because we just have these negatives. So, at the start, my approach was just to print, and from these self portraits I printed the entire two rolls. This was the first week – it was just this random process of picking stuff out of boxes, and then Līga would start with the archiving three days later. I don’t speak Latvian, so Līga always sends me information about what things mean. Zenta was pretty good at archiving herself – there are notes on all the negatives. We have a four-person chat with Zane, Līga, Alise, and me, and we share information, and Alise tells us who the people in the images are.

Līga: The first series had this very beautiful and ironic note to it that said: “Me as a photographer when I didn’t get into the academy.” In others, we sense which negatives she considered successful – you can see her thought process. For example, you can see marks like “this is good”, or ironic notes, like, “making big art”.

Sophie: Yes, neither Līga or I know her, but she sounds like someone with a very good sense of humour.

“I Don’t Remember a Thing: Entering the Elusive Estate of ZDZ” at Kim? CAC. Exhibition view. Photo: Kristīne Madjare

Ieva: Alise, you have this lovely article about Zenta on the MoMA blog, and you refer to her as a “para-feminist”. Can you say a few words about what that means.

Alise: That’s also a problem, because when you write for a US audience, there is an expectation that you will label the artist and put every artist in a very specific box. Of course, when you talk about any woman’s artistic practice, and especially about Zenta’s practice, there is this question of how it is related to the ideas of feminism.

But the situation was completely different in the Soviet Union at the time. The 60s was the time for feminism in the US and some Western European countries, but in the Soviet Union that absolutely wasn’t the case. It wouldn’t be correct to say that her practice was “feminist”, because those were not the ideas and the concepts that she would work with – it was not in the air, it was not around, people didn’t talk about things like that. It was just a different cultural context. There are scholars who write about “proto-feminists” or “para-feminists” who were working in the spirit of feminist ideas, but not self-consciously moulded in that way. So, that was my attempt to give the reader what they expect, because they would definitely ask – Oh, we see a woman’s work and there are naked bodies, so what about feminism? And how is it related to it?

It still needs thinking and theorising, and trying to understand how we can talk about our artists to audiences that are used to this linear chronology in which feminism appears at this time, but in our lived experience, it’s different.

Zane: It’s not just in the 60s and 70s. To give an example, at Kim? we are now working towards a project with the artist Ieva Kraule-Kūna, whose solo exhibition will centre around her personal memories of growing up in 1990s Riga, how this period has impacted her and her peers, and how its “wild” imprint may still continue to impact us. While researching and thinking about the 80s and 90s and how female artists in Latvia positioned themselves, theorist Jana Kukaine brought to our attention the term “latent feminism”, which, similarly to the term “para-feminist”, could be applied to describe the motives and modes of working by those women artists. Meaning, being either “unconsciously” or “unwillingly” feminist.

Alise: Regarding the terminology, we really have to work towards understanding how to talk about this work. Because, of course, from what I remember from conversations with Zenta about her work in the 60s, she was very well aware that she’s alone or almost alone as a woman in this man-dominated space, and she was very well aware of what images of women were expected and accepted in that environment. Her practice was going in the opposite direction also consciously, but we couldn’t say that it was the same as with the artists working in the US strictly within the discourse of feminism.

Zane: From this angle it’s really interesting in relation to what you, Sophie, said about the artist Zenta, in the 60s and the 70s, paving the way for the work that you can do. Also, the attitude that Zenta had – even though she may have had a good sense of humour and an opinionated mind, she may have not been so openly ready to conform or align herself to the likeness of a photographer, of an artist. While for Sophie, this is not even a question.

Sophie: And, also, that she was really working as an artist, and she wasn’t interested in photography for photography – this very technical and proper approach of making proper images. I think it’s also a link that Zane and I talked about, as Zenta did a lot of experiments in the darkroom with solarisation and photograms. And it’s really great to see that she wasn’t trying to make pleasing work, but that she was making art, which of course is a tough choice because it often results in less visibility.

Alise: Yes, that’s where it ends, in the boxes in the storage, in the darkness. I think that’s very precise what you say about “pleasing images”, because that is what is expected from photographers, especially in the context of Latvia. You make something that is nice to look at – beautiful images and nicely printed. And the content is also, like Sophie says – pleasing. For Zenta, that was never the goal; she was more interested in, as I understand it, something that results in an image that is interesting for herself as an image, but that is not necessarily a pleasing one.

Sophie: It’s kind of radical to remove oneself in this way.

Zane: Yes, it’s interesting what you say about removing oneself. I think that in her practice, she takes different directions in her series. From the nudes – either herself (albeit, very seldom) or her close female artist-friends in the studio, to the very documentary-style images of the countryside. All of them are equally interesting and captivating, and there may be no thread or link between the various series, but they all feel very fresh to me.

Ieva: And, so, what is the future of the archive? We’ve been talking a lot about this exhibition being very performative, and that the pictures are also performative, and the act of people being here is very performative, but what are you planning to do with the archive and the images later on?

Zane: Speaking from Kim? as an organiser – we have a great photo documentation of the exhibition by the photographer Ansis Starks, including the process in the darkroom with Sophie as well as the growing display. Next, we will start sending them out to the media, focusing on various international contemporary magazines and online sites. A good review is always really appreciated, but due to the state of art criticism in Latvia, and the limited financial resources to fly international reviewers and critics to Riga, we may not end up receiving one. So there is a definite interest in at least securing an online presence of this project via installation photos. In terms of the archive, Alise, as the person who owns it, may elaborate more, but I know there is talk about donating the archive to a certain cultural research institution in Latvia, as well as Līga continuing her research and archiving work with it.

Alise: Yes, it would be ideal that this part of the archive would be housed in a professional cultural institution that has the materials and circumstances to keep it, and to continue the research. Yes, Līga is also interested in continuing working with it.

Līga: Definitely. I mean, two months to work with such a huge archive is not enough time to systematise it – I can only start to understand what is in there, what was Zenta’s thought process organising her work and what will be my next strategies. It is important to be respectful towards her system. There’s a lot of work to do. And considering the archive’s past and future, you can think of it through the concept of trajectories. The biography of the archive changes throughout the years. Starting in the 60s and 70s, when the photographs were made, and then put away and forgotten. And then resurfacing in the 90s as the perceptions of photography started to change; and then around 2010, when the National Museum of Art started to take an interest in collecting photography, they included Zenta’s work in the history of Latvian photography. And then through the years there is Alise’s work in making Zenta’s photographs visible internationally; and now Zane’s interest and Sophie’s work open new interpretations and hidden gems. There are so many more possible trajectories from now on, and possible storylines that can come out of this archive content-wise and in relation to the history of photography.

Sophie: I also find it interesting that Līga, in the context of this exhibition, is performing archiving. It’s this additional layer. It’s not only archiving, but she’s also performing.

Zane: This “elusive archive”, as Alise called it in the article, becomes less elusive and more “tamed” in the most positive way as, with the help of Līga and Sophie, it gets more revealed, layer by layer and negative by negative. There’s also Sophie’s imprint, where the new work will end up in another circulation in her context. Zenta’s work will undeniably become more known and, maybe for some people, kind of hard to pinpoint, which is also the reason for this exhibition – to break up these molecules into a system.

Ieva: For me, what is interesting in this show is not only the concrete context of Zenta’s work, but also the way you’re thinking about archives and preservation. I think that usually, if you would ask someone whether this or that archive should be preserved, they would say yes. But, then there are all of these questions – how do you do it, how do you store it, who gets access, and how can it be used and seen? What Sophie already said before – if this were the property of an institution, you wouldn’t have access to it. How do you find this balance between preserving the material and also having it be active and existing in the world – so that it doesn’t die because it’s so removed from people? Here we see a different perspective on how an archive could be used – not only by giving it life, but also in terms of preservation, as there is someone who is going through the negatives and someone who is making them visible.

Zane: It's all thanks to the trust, agreement, and genuine interest from all involved parties. Also, there’s no forced agenda to monetise on this in any possible way.

Sophie: It’s also thanks to the owner of the archive, Alise, who allows us to have access and who and takes care of it because it does require a lot of maintenance. Thanks to Alise, this archive even exists, because it must be assembled and put it into boxes, stored it in a safe place which which has to be rented, then transported over here, etc. It’s very much about generosity, generations, and maintenance work, which also Zenta did a lot of. Archiving is also the same, so, Līga, your job is really keeping the memories safe and sound.

Līga: I also love how this exhibition is educational. If we go back to what you said in the beginning – that people throw out their archives and they just perish, and if we think of an exhibition as an educational way to show people how to treat photographic objects, then maybe there will be more archives that will resurface. Hopefully. You never know what’s in the attic.

Ieva: Alise, what would be the perfect future for this archive, from your perspective?

Alise: I like what Līga mentioned about the possible trajectories and being able to keep it open. I like the idea of multiple futures.

From left: Alise Tīfentāle, Līga Goldberga, Sophie Thun, and Zane Onckule. Photo: Kristīne Madjare