On the trajectory from idealism to realism and back again

Q&A with curators Alaina Claire Feldman and Zane Onckule about the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre Festival “EDEN: Coming of Age”

“Eden: Coming of Age” (July 7–August 3) is not only the title of the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre's festival, but also a symbolic inquiry into the notion of coming of age – for the institution, for the artists, and for the audience alike. Having reached the age of sixteen, Kim? reflects on its journey so far while also exploring what it means today to be young, to remain within “the process”, to make mistakes, and to learn anew.

In this conversation, curators Alaina Claire Feldman and Zane Onckule address questions of: institutional maturity and the experimental spirit characteristic of adolescence; the role of education; the impact of space on content; and the creative process as a form of self-education. Their international experience, mutual trust, and shared curatorial vision allow the festival to be not only a moment of celebration, but also a conceptual statement for the future – navigating between idealism and reality as well as between institutional responsibility and independent, critical thought.

How do you see the idea of “sweet sixteen” in the context of an art institution? Is it a sign of maturity, or is it still a time for experimenting?

Zane Onckule: While the age of sixteen (sweet or not) is believed to be a testing ground – the pre-adult threshold for a person still at a tender age – for an art institution, it is already a sign of resilience, mindfulness in one's actions, and duty towards one’s community. In an art context, things don't just happen on their own – there’s a whole operation in place. We can, of course, draw parallels to a family institution where parents or guardians ideally guide and take care of their teen. Kim? was born on the background of the global financial crisis and following the uncertainty of the late aughts. Arguably, not much has changed or improved – perhaps even the opposite has happened. And yet, by learning, doing, failing and succeeding, we have managed to build an infrastructure that both reacts to and works around shortcomings and limitations, and celebrates the richness of cultural activities from the region. As we embark on new ambitious projects (the institution’s new future venue, an art fair…) that do imply maturity and a clear direction, we do promise to hold onto the pleasures (and at times, adorable confusion) of youthfully charged experimentation. Be sure that we will jump upon the chance whenever there is room for more rambunctious maneuvers.

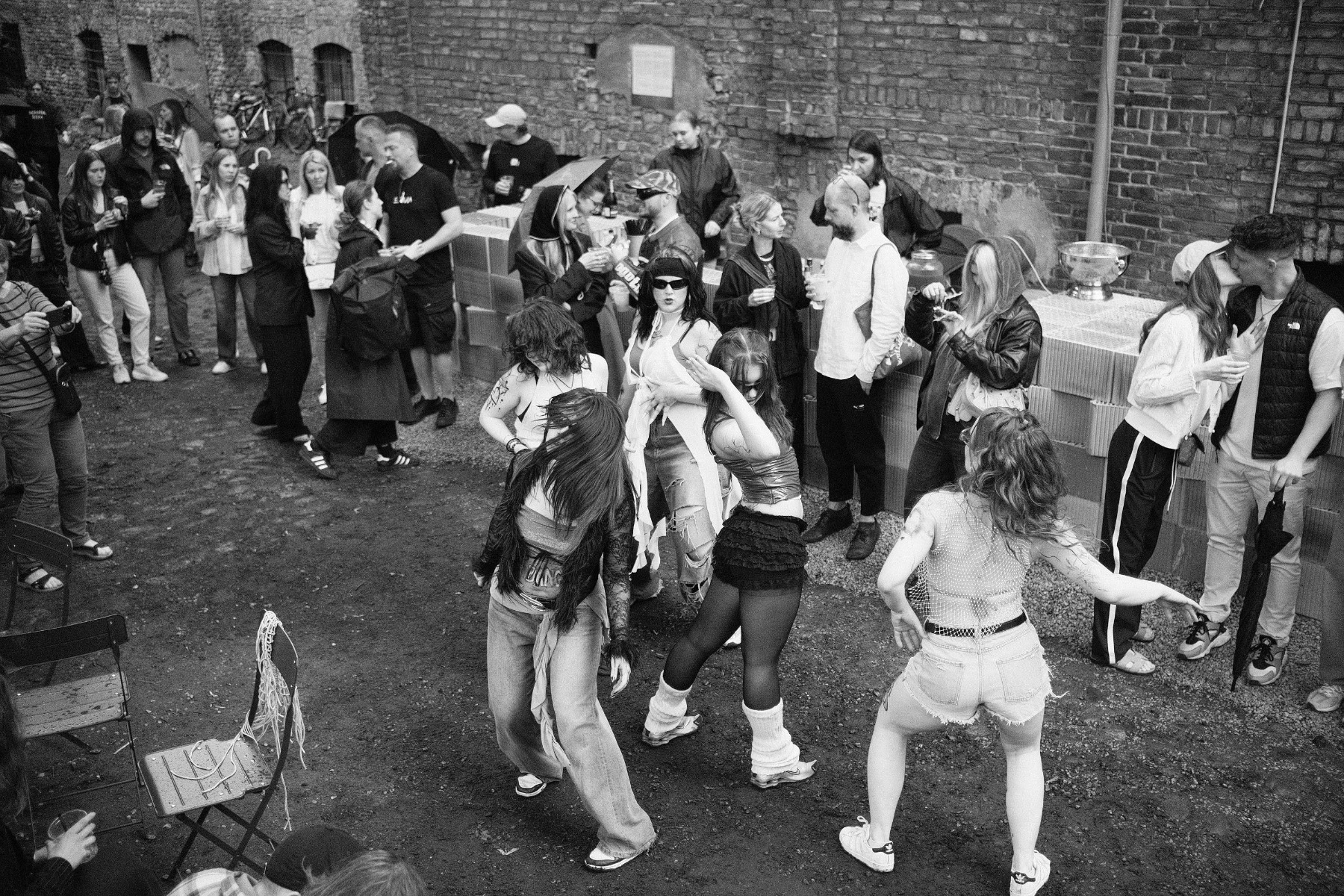

Opening event of the festival “Eden: Coming of Age”. Photos: Ģirts Raģelis

Alaina Claire Feldman: Why do we always assume turning sixteen is a sweet affair? In this project, we present the notion of sweetness as something to satirize and question. Turning sixteen is full of growing pains. It's awkward, frustrating, full of doubt, and can feel like you’re stuck in a liminal place between childhood and adulthood. Sixteen is also liberating when one starts to understand oneself as an individual with a certain amount of autonomy. You experience your body changing, you try on new styles, or start a new hobby to see if it vibes with the internal idealization you have of yourself. For sure, it's a time of experimentation, but it's a process that gets you on the road to a more confident sense of self.

How is the process of growing up reflected in the structure and content of the festival – from idealism to a more realistic view of the world?

ZO: There are various dimensions here. Perhaps less visibly to an outsider’s eye, it has to do with the practicalities and logistics involved in making an exhibition, an event of such a nature...or any other kind, really. Art takes time, attention and resources, and requires a whole lot of money. Working around these constraints can be challenging at first, but it actually presents an opportunity to learn and get the unexpected out of such negotiations with the pragmatic. The festival is set in a very peculiar space (a historic and unrenovated end-of-the-19th-century yeast factory that once housed several educational institutions, but most recently, has stood empty for nearly a decade) that, at this present moment, conveys more future promise than it can practically offer. Imagination and patience were our tactics here. Significantly, the participating artists and their works – both new commissions and earlier work – showcase their own unique relationship and dynamics that go into the creative process and thinking as we mature, develop our creative practices, and simply age. Going through the exhibition, we shall pick up themes addressing contemporary digital alienation, askew perceptions of reality, notes on education, and romance and drama – as well as the general joy and doubts that are prevalent in everyday life. It should come as no surprise that none of the participants are actually sixteen years old; instead, the exhibition gathers a wide swathe of generational artists in their late 20s up to their mid-70s, which, in turn, evokes the notion of longing...a certain sentiment of the past. The festival’s trajectory of idealism to realism and then back again is also addressed in the exhibition's title, which has two versions, one each in Latvian and English – “Sweet Sixteen” and “Coming of Age”, respectively. They convey slightly different tonalities, yet both feed into our attempts to hold onto idealism while being largely attuned to reality.

ACF: And we have had teenagers and young folks joining us and participating – from Kim? gallery volunteers to Art Academy students who have built a very cool outdoor bar and seating area in the courtyard. It's been wonderful getting to know them, working with them, and getting their feedback.

Do you think an art institution needs to keep some “teen spirit” to stay alive – as in being unpredictable, sensitive, and open to experiments?

ZO: Certainly. While of course the “teen spirit” of Generation Alpha is nothing close to that of ours growing up in the 90s, we still do perceive it through a prism of rebellion and acting out against the confines of reality. Used wisely, it offers an invaluable, almost self-therapeutic tool that acts as a filter and blocks out things that, in the long run, would eventually prove to be insignificant, if not damaging. Being in sync with the world and its processes, sharing your curiosity with others, and never ceasing to question and doubt should be in every art institution's code of conduct manual.

ACF: One thing that is so special about Kim? is its autonomy. It doesn’t sell tickets, the exhibitions don’t have to cater to a populist agenda, and it supports many different kinds of artists – and so it can challenge the status quo. Kim? has been doing an amazing job with presenting artists from different generations and geographies who think critically and model new ways of approaching culture, form and politics. As curators, we are old ladies now, but I think we still “smell like teen spirit”.

ZO: It’s fitting to add that an art institution is not an abstract entity; it is made up of people who are part of the team or join it for their particular case. Our festival is surrounded by a group of young individuals – mediators and assistants – whose enthusiasm and curiosity greatly contribute to our stance against the growing disbelief of the coming future.

Can this year’s festival be seen as a kind of self-reflection for Kim? – also in terms of space, as the institution is moving to a new home on Hanzas iela?

ZO: Yes, in a way it does. Making analogies – our new building, which is a far cry from the more conventional white-cube setting, could be considered as a teenager’s new and larger bedroom as they move away from their childhood home. A testing ground and platform away from controlling parents, where one can express oneself in a somewhat new – yet at the same time, mindful – way.

How do you deal with the tension between a high level of professionalism in the art field and the wish to keep on asking open, maybe even naïve, questions?

ACF: I always start with the artists. What do they want to do, and how can I help them best communicate it to different people with different experiences and educations? My background is working in museums that are embedded in universities, places where my audience is made up of both very established international scholars and teenagers who are living away from home for the first time. Being able to communicate art to both professionals and nonprofessionals is a question of accessibility.

ZO: I would add it’s all relative, especially since I am interested in friction, commonalities and dissimilarities between various contexts where such “high levels of professionalism” are present. Undeniably, Riga and, say, New York, are at opposite ends of the spectrum in regards to institutional organization and funding schemes, but also regarding access to resources and the general discourse and discussions across art scenes. What may appear as high professionalism in one place could be a target to contest against in another place, and vice versa. In Riga, I feel art institutions are in a more horizontal (communication) level with artists, and their institutional power manifests way differently than in the much more smoother machine-engines of the larger institutions found across the mainstream West. All in all, the very tension between the high, the low, and everything in between is what drives us forward.

Why is education such an important part of this festival? How is it connected to the building’s past as a place of learning?

ACF: Our focus on education here is literally reflective of the site-specific history of the building as a former school and college, but also in terms of how being sixteen and coming of age often takes place within the context of schooling. We increasingly lose our innocence the more we are educated. The location where education is taking place, what’s being taught, and who's doing the teaching all have huge implications for the kind of thinking and ideologies we subscribe to. In the US, we see the government trying to consolidate power through eradicating the Department of Education and suing colleges in order to eliminate them. At this critical time, Zane and I were drawn to artists who challenge the way we think in order to evaluate the world around us. For example, Aura Rosenberg’s photographs challenge questions of power between parents and children, between the established artist and the amateur.

ZO: Education and lifelong learning was something that we were keen to explore and display. The exhibition also houses the product of an actual learning process, for example, the workshop by Art Academy interior design students, which has resulted in an open-air public stage/bar now set in our adjacent courtyard, “The Garden of Eden”. And yet, our exhibition is not intended to be a certain all-encompassing survey of the state of education or learning. Instead of being didactic, through artist interventions we aim to evoke more indirect reflections on the state of learning, knowledge accumulation, and your own interaction with that, even if it has more to do with the opposite, namely, “unlearning”.

The lecture titled “We Don’t Need No Education” and the Bootleg Library illustrate different ways of sharing knowledge. What do they say about learning in art today?

ACF: That’s a great question. While the lecture will be delivered in a traditional format, the Bootleg Library allows one to select and pirate their own learning adventure. But if someone wants to make a bootleg recording of the lecture, I’m all for that! The lecture will actually contradict the notion that we don’t need education. In “The Undercommons”, which we quote in our entry wall text, Stephano Harney and Fred Moten aren't suggesting we totally abandon our schools, but rather that we inhabit them differently, from a place of more equitable power. They suggest that we’re not all permanently naïve or in debt to someone/something. Instead, we build an active intellectual and cultural life with one another that comes from underneath what’s typically tolerated and expected.

How did you choose this group of artists taking into account that both you and they represent different countries, generations, and levels of experience?

ACF: Zane and I have known and worked together since 2011! She’s an incredible person to collaborate with. Because we’ve known and respected one another for so long, we had a good sense of what the other wanted for this project. We both wanted to bring a sense of humor and play into our work. We didn’t want to explore youth as something to be embarrassed by, or something nostalgic, but rather as something to continue to learn from. We presented artists to one another and talked about how the works might speak among themselves, how they could respond to the site, and how they would be understood in the local context of Riga.

ZO: I have admired Alaina’s curatorial practice for more than a decade now. I really enjoy the way she seamlessly blends rigorous academic research with, at times, a more guerrilla/DIY aesthetic and approach, be they related to curatorial decisions or the artists she chooses to work with. Her roster of artists is very diverse and not easily bracketed. We wanted to reflect that in this exhibition as well. Through inter-generational artists and both new and older works, we have ended up with a line-up that evokes a dialogue between the American and Latvian contexts, keeping in mind that a large part of the artists in the exhibition are in constant movement across different cultures and either live abroad or frequent other locations. We were also interested in cross-collaborations between the artists, and this is represented by artist duos/collectives that have either worked continuously together (GolfClayerman, Daniel Chew & Micaela Durand), or are premiering a new collaborative work (Ella Kruglyanskaya & Alan Reid).

Performance by Miho Hatori. Photos: Ģirts Raģelis

What role do you see for performance in today’s art institutions – is it a show, a ritual, a conversation with the audience, or something else?

ACF: During the opening we had an amazing performance by Miho Hatori (joined by Aleksandr Aleksandrov from Riga and John Miller from NYC) who performed “Salon Mondialité”. This is a piece she’s been working on for several years that appropriates the late-night talk show format in order to investigate political questions around building one's identity through a kind of creolization (as posed by the philosopher Edourard Glissant). Zane and I loved Miho’s collaborative highbrow (philosophy) and lowbrow (television) way of thinking through modern identity formation. Performance is a fantastic way to gather a group of people within the art institution and build relationships around a shared, time-based experience. We often see exhibitions done alone or in small groups, but it's through performance that we create an immediate collective awareness. To connect back to your earlier question of study and education, a performance in an art space allows us to get together because we want to learn something new through art, not because we’re getting graded or due to some other objective. Simply because all we want to do is learn something together.

Photo: Ģirts Raģelis

How do you see Kim? in the international art scene – are there other institutions of a similar age that inspire or reflect your path?

ACF: There’s nothing like Kim?.

ZO: Throughout the years, Kim? has been inspired by both established and widely respected institutions such as PS1 in New York, Chisenhale Gallery in London, and numerous others. We were, and still are, also looking at various lesser-known initiatives, be they artist collective-run spaces, independent magazines, or other kinds of creative manifestations. As we go on and continue “ageing”, we change our priorities and points of reference. Nevertheless, while our Pinterest board may gradually change, we do hold dearly to our visitors who, we hope, are continuously willing to embark on this journey with us together. It is as with staging “EDEN: Coming of Age” (or Sweet Sixteen), we whisper in your ear those famous lines from the early 1990s song sung by Latvian pop diva Olga Rajecka: “.. but will you still love me, will you come to me... when I’m no longer sixteen?.. no longer sixteen?”.