Each painting is a kind of equation

An interview with French conceptual artist Bernar Venet on the occasion of the exhibition of his paintings at the Museum Riga Bourse

A Corten Steel bar lies horizontally on the floor; above it is a minimalist inscription in French: The Line Instrument. The Trace of the Line as a Tangible Memory of the Pictorial Gesture. / La Ligne Instrument / La trace de la Ligne comme mémoire tangible du geste pictural. A white wall augments the space with an inexplicably sacred dimension...as if it has already experienced what has not yet happened. In April 2023, I was waiting for the start of Bernar Venet’s performance – along with about a hundred other people, i.e., as many as, at that particular moment, could fit into the lobby of the Perrotin gallery in the Marais district of Paris.

Is it possible to to put an equal sign between the radicalism of an idea and its sacredness? Dressed in all black except for white gloves, Venet grasped the line (or more precisely, a large steel bar suspended by a cable on one end), covered it with paint, and then with a strength that was at once elegant and light, swung it along the white wall. This action left on the wall an imprint of paint, gesture and its intensity...and at the same time, a space for unpredictability – for a dynamism to occur between the line and the material, between form and force, between the rational and the natural, and between the strictness of a line and the arbitrary flow of paint. In this case, the line embodied both roles – subject and instrument.

I didn’t note the precise length of the performance, but it definitely went on for more than an hour. Two impressive imprints/paintings were left on the wall of the Perrotin gallery, and at the end of the performance, the steel bar was returned to its original position on the floor. “Pushing the limits of art is my only goal,” said Venet. To not get stuck in that which exists...to go beyond what has already been – the approved, the accepted...to expand the cultural space and that, which is human. To experiment – every day and without cease.

And that is precisely what he did that afternoon – physically, mentally, artistically, humanly; redefining boundaries, again and again...between performance, sculpture and painting. Throughout the performance, Venet’s face was never without a smile indicating that he was intrigued, fully immersed, and enjoying the process. It was the same smile I saw on his face in October 2019, when his monumental environmental object – the 250-ton, 60-meter-high Arc Majeur – was unveiled at kilometer 99 of the E411 motorway in Belgium, between Luxembourg and Namur. It still holds the record for the tallest work of environmental art in a public space...his great dream, which took exactly 35 years from the moment the idea was conceived to its realisation. “Arc Majeur is an extraordinary achievement in the field of art,” Bernar said at the time, stressing that the arch was a collaborative project between the artist and engineers and specialists in various technologies.

Three Indeterminate Lines. 1994. Rolled steel. 273x300x430 cm. Exhibition view: Champs de Mars, Paris, France, 1994. Photo: Archives Bernar Venet

The line – its mathematical and physical manifestations – has been a central element in Bernar Venet’s work since 1976. He has always been intrigued by its challenges – curves, angles, straight lines, arches – which, depending on their various configurations, can embody order, chaos, transformation, collapse, unpredictability…

The performance at the Perrotin gallery was part of his solo exhibition, which was shown simultaneously in all four of the gallery’s locations – a first for the Perrotin gallery in terms of an exhibition by a single artist. In connection with this event, Venet’s La Parabole de l’Histoire was also put on display in the Place Vendôme.

Bernar Venet is one of those artists for whom one could say that ambition and scale are natural endowments and come to him very organically. He is tall and exudes a charisma that is positively infectious, just like his energy. At the time of this interview he was 83, but these two digits could just as easily swap places – their objectivity and subjectivity have equal relevance.

Shortly before his birthday, Venet opened an exhibition at the Marciana National Library in Venice during the 60th Venice Biennale. It was entitled Bernar Venet – 1961...Looking Forward. In 1961 he was only 19 years old, and at that time he began to experiment with simple materials that were new for their time, and which would later become the hallmarks of his creative exploration: tar and cardboard. His now iconic Tar Paintings, Cardboard Reliefs, and two other installations were now being exhibited in Venice. In the sumptuous interior of the Library – alongside paintings by Tintoretto, Titian and Veronese – Venet’s works embodied an absolute quintessence of modernity without losing a shred of their original radicalism...once again, leading one to ponder the relativity of the concept of time in the context of the radicality of ideas. His first solo exhibition in Venice took place in 1978, during the 39th Venice Biennale, whereas in the autumn of 2024, a retrospective of his work – a tribute to 65 years of his career – opened in Beijing.

“I have a theory about working in art. There should be a heroic aspect in the process of creation. The first is, of course, the radicality of the idea. If you think of Malevich, it was extremely heroic of him to imagine, in the 1910s and 1930s, doing something that was totally impossible for people to understand. And, in a sense, quite impossible for the artist himself to comprehend, too. Because you don’t know where you are going when you do something like this. You have no idea if people are going to follow you and one day understand if what you are doing is important and will be appreciated in the future. So, that’s one thing – the radicality of the idea. The second is when you do art that shows that you have invested yourself completely and put all your energy into it. You do art because this is what you are supposed to do. And you do it,” Bernar told me in an interview in 2016. Our conversation took place at his foundation in Limeuil, a town in the South of France that is also the hub of his experiments, research and thinking. In 2024 the foundation celebrated its tenth anniversary. Bernar marked it with a performance during which he “pushed” 20 gigantic, vertically arranged steel arches, each weighing about one ton, with his bare hands. They collapsed in a breathtaking dance between chaos and balance, almost metaphysically resurrecting themselves by creating a new, previously non-existent combination – a possibility trapped within chaos.

The idea for an exhibition of Bernar Venet’s work in Riga sparked in 2017, when the Latvian National Museum of Art presented Jewellery by Artists: From Picasso to Koons, an exhibition of jewellery created by Venet’s wife, Diane Venet. Bernar was present at the opening, after which he remarked, “I was so impressed by the space, and I am honoured to have been invited to present my paintings to the Latvian public.” The exhibition at the Riga Bourse Art Museum features 28 paintings by Bernar Venet, each of which embodies the possibility of a completely new point of view.

Exhibition view: “Bernar Venet, The Conceptual Years 1966–1976” / Musée d’Art moderne et d’Art contemporain (MAMAC), Nice, France. 2018–2019. Photo: François Fernandez

“You never set out thinking, I’m going to do the most abstract thing that anyone has ever made. No, you don’t think like this. You just live the adventure. It’s like you’re on a boat, and suddenly you see an island where nobody has ever been before. You cannot say what this island is going to be. You go there, you walk on it, you discover things. And then you can say this is what I discovered. It’s the same in art – you cannot say I’m going to work on this or that concept. You just experience, experience. You experience things, things that are typical to your nature, and then one day you can look back and say this is what I did. And then you see the relationship between all the work you did.

5Y (Minus). 2001. 56x76 cm

What I’m going to say now, I realised it only five years ago. Ever since Malevich, Kandinsky and others, we know what abstract art is. We know what it looks like, and we also know all of its possible variations. They’ve all copied themselves in countless ways – in larger and smaller formats and so on. But here I’m presenting a painting (because it’s on a canvas) with a mathematical text that can sometimes be read. And it’s true that this painting doesn’t look like an abstract painting at all. And still, when the text is a mathematical text, I’m definitely presenting a painting with the highest level of abstraction that a work of art can present. Because what can be more abstract? Color can always mean something. Blue can mean the sky, green can mean nature, and so on. But these paintings have absolutely no relationship with the real world. So, it’s totally, totally abstract,” Bernar said in our conversation back then; the following is its continuation.

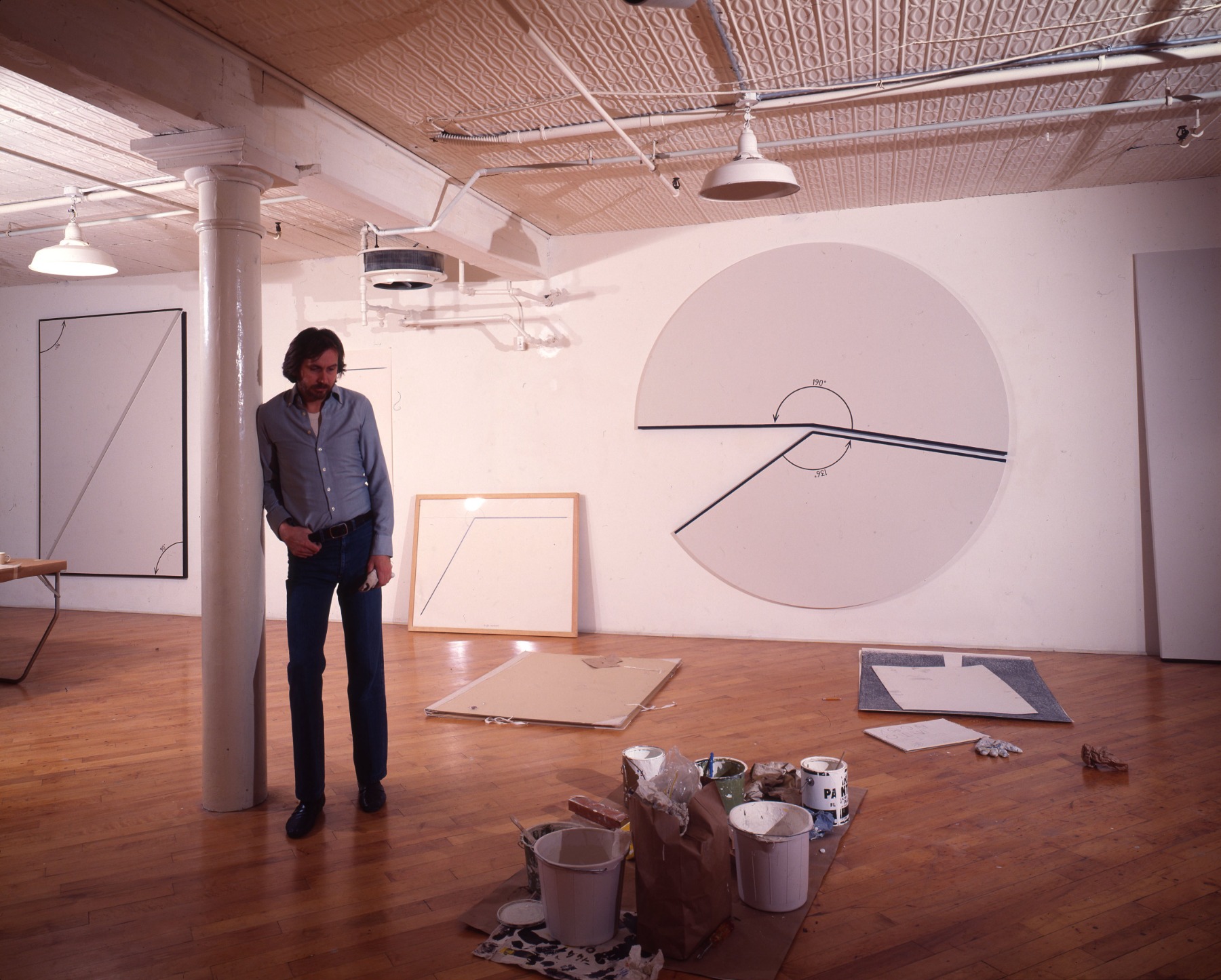

The artist in his studio on

West Broadway, New York, NY, USA. 1976. Photo: Archives Bernar Venet

In your career of more than 60 years, have you come to understand what creation is?

For me, the creative process is driven by curiosity, continual questioning, and a permanent desire to discover other unexplored areas. My entire body of work is made of pauses, new beginnings, experiments that draw on delving into the past. That is perhaps what allows me to continually broaden a gestation into an endless questioning. So much remains to be created. I am convinced that art as we once lived it and live it today is only a stage in knowing and sharpening our sensitivity. Let’s accept that the parameters that define what art is nowadays will have nothing to do with those that will become the norm tomorrow. It is our chance, for it will be proof that art, as a field of knowledge, will always keep that precious possibility of being able to renew itself indefinitely.

The artist’s studio in New York. 2002. Photo: Archives Bernar Venet

The distance between a work of art and mathematical equations or diagrams with theoretical applications seems vast, but something changes when painting brings mathematical language into the field of art. What does this shift do to mathematics, and what does it do to art?

The language of mathematics, with its equations and symbols, had no place in art before I introduced them in my work.

The role of artists, by which I mean those who can and want to push beyond previously-accepted limits, is to introduce new concepts and new representations in their work.

For example, in the fourteenth century it would have been inconceivable for an artist to paint a landscape or a still life. Similarly, would it have been conceivable, during that century, to take a very simple geometric shape such as square or a triangle, and present it as an artwork, as Malevich dared do in 1914?

The whole of Western art history, since the first representation of religious and mythological scenes, is testament to a constant evolution in terms of what subjects have been considered suitable.

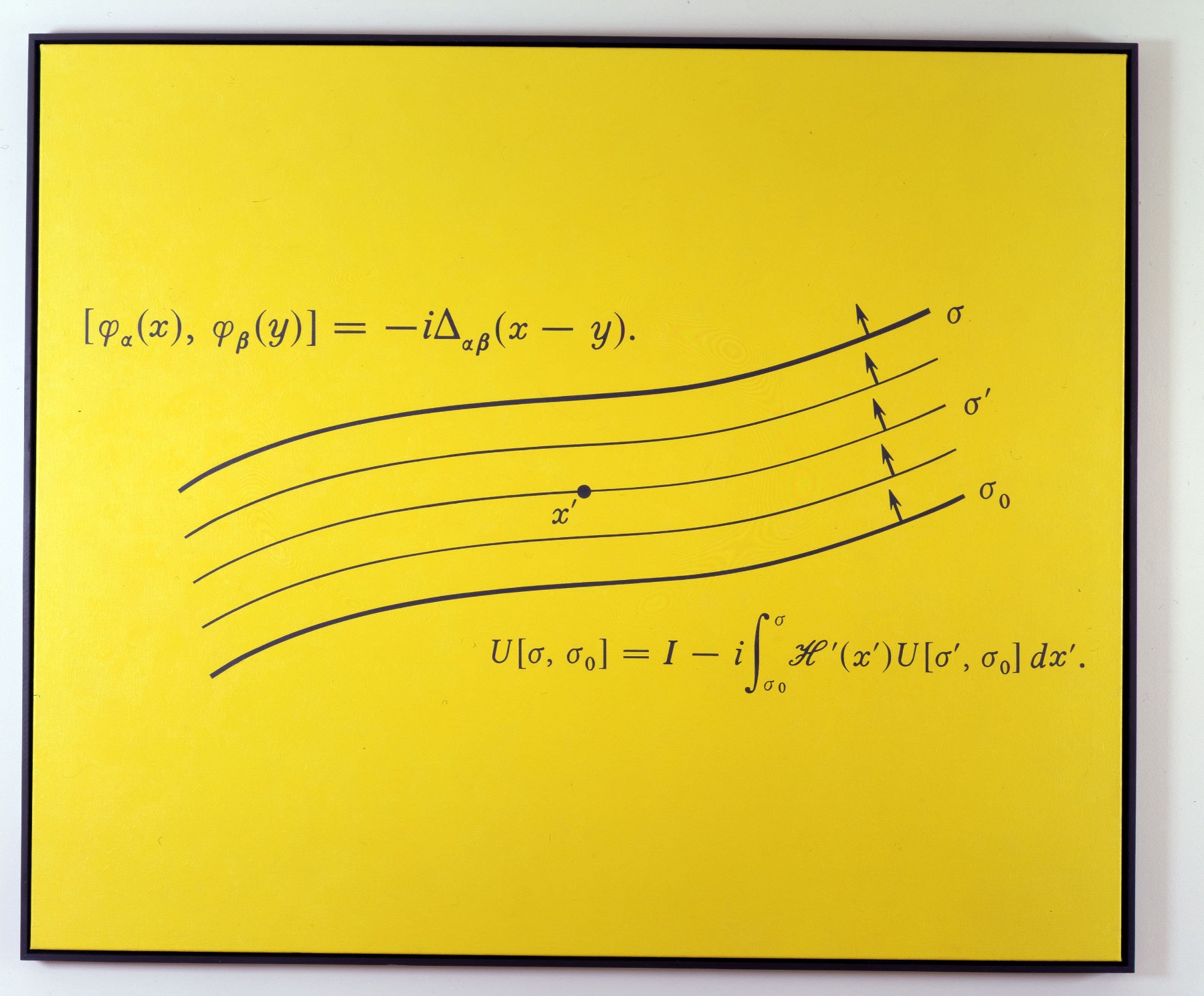

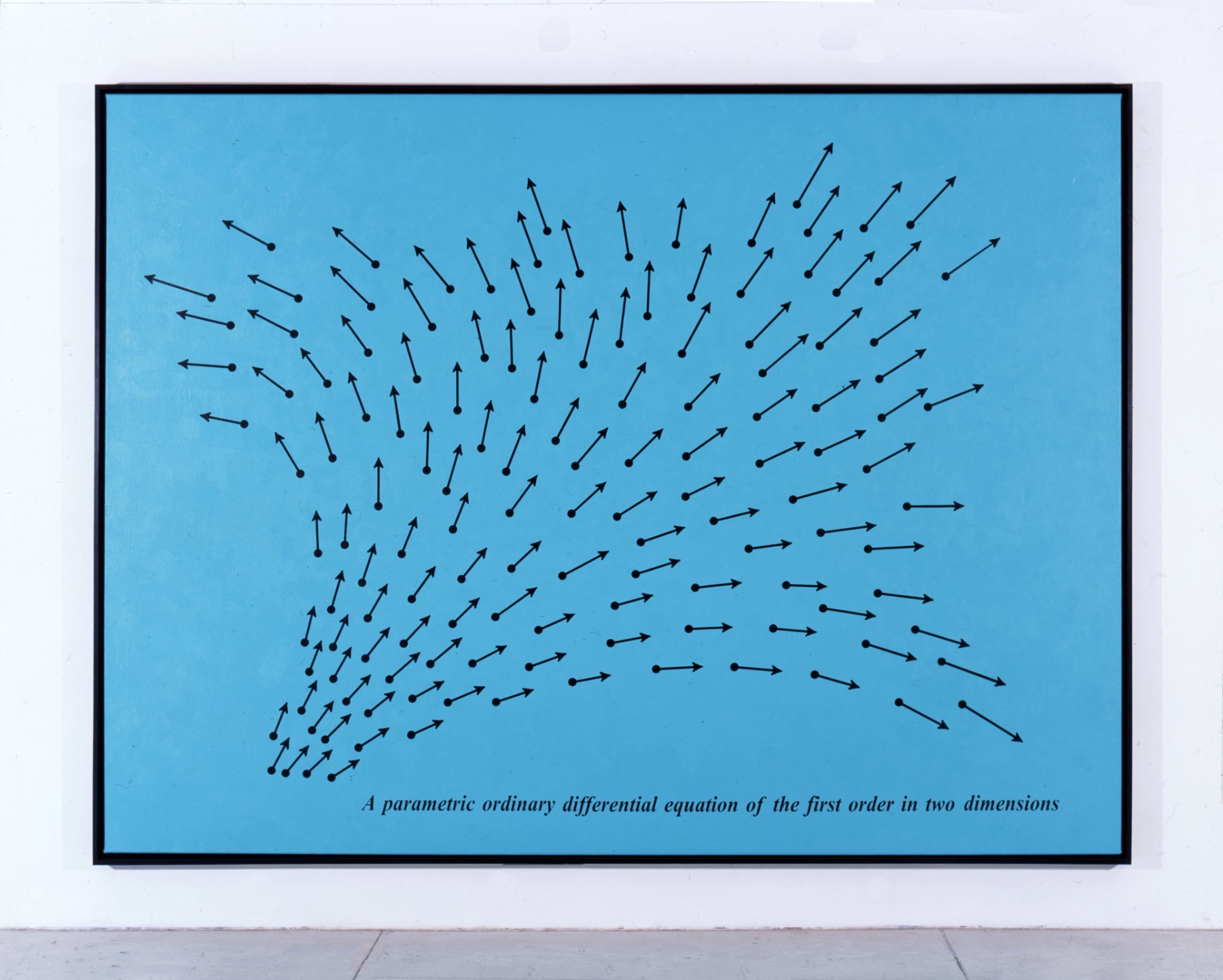

In 1966, when I made my first paintings representing mathematical diagrams, my aim was nothing less than a radical renovation of the visual vocabulary. My paintings were no longer figurative or abstract. In this way, I could present pieces that semiotics defines as monosemic, in other words, with only one level of interpretation. That was a major paradigm shift and the start of my whole Conceptual period which lasted from 1966 to the end of 1970.

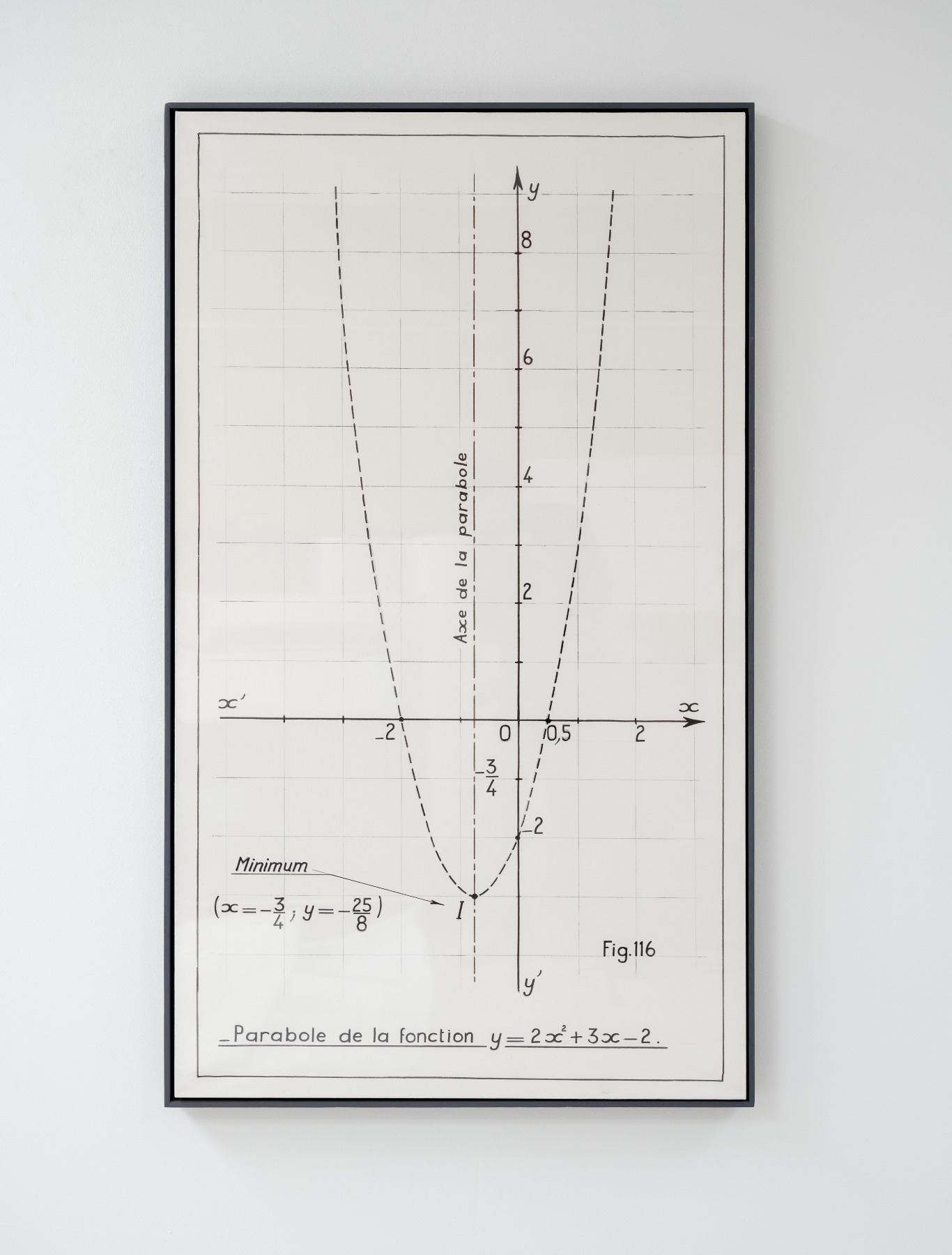

Parabole de la fonction

y=2x2 + 3x-2. 1966. Acrylic on canvas. 171x100.5 cm

When speaking of your work, you often use the word “monosemic,” which, in a way, embodies the essence of purity – a moment of singular meaning – without assigning any additional interpretation to the canvases that present mathematical diagrams and the abstract language of formal logic. What attracts you to pure science as a subject for art?

I use mathematics without being a mathematician. I don’t necessarily have to understand all the symbols that constitute the mathematical universe in order to make use of this discipline.

For me, the important thing is to have some understanding of what math is. You don’t have to be an expert. Take, for instance, Cézanne, who painted trees, plants and flowers. Was he an expert in botany? And Malevich, who painted angles and squares, was he a geometrician? Does an artist who paints nudes have to be an anatomist? We have to understand that, over time, religions, societies and scientific fields have become subjects for art that have allowed art to move forward.

My work mainly consisted, through the use of language and mathematical diagrams, in implementing a new system of symbols considered monosemic, which means purely self-referential. I wanted to widen the field of what I thought was redundant art by introducing disciplines usually considered to be outside the realm of art (stock markets and meteorology, for instance), by presenting their precise, objective and rational character. This is a non-expressive approach to art. The exploration of this approach in various media (performance, poetry, sound, television, etc.) enabled me to criticize the notion of style as early as 1967. Only the content needed to be taken into account, not the stylistic aspect and artist’s personal touch.

We can differentiate three categories of visual messages: so-called “polysemic” figurative messages; abstract images called “pansemic”; and those that belong to the domain of precise, logical diagrams called “monosemic”. The first two categories are defined by the multiplicity of meanings – “pansemic” figures are open to an infinite number of interpretations. What makes “monosemy” unique is that there is only one possible interpretation. So when I first turned to mathematical diagrams in 1966, I positioned myself outside of the usual fields of art. This is the unique significance of the rupture that arose from my semiotic reflections.

Square gold painting

with diagonal numbers. 2010. Acrylic on canvas. 200x200 cm

By turning mathematical equations into art forms, are you, in a way, adding an aesthetic dimension to them? Or quite opposite – by using mathematics as an art form you are bringing us to the purest essence of art and life – which is mathematical? What are words, letters, and mathematical symbols for you? Are they raw materials that you experiment with, providing the viewer with unlimited possibilities?

If I choose mathematical symbols, it is for rather clear reasons, which are directly linked to purely artistic questions, since these bear on the problem of the identity of a work of art and its specificity. It is well known that in the 1960s I developed a body of work termed “conceptual”, which used language and mathematical figures. In a certain way I am returning to that now, but with different ambitions. You ask me the reason for this choice; I would say, because it involves a radically new language in art, a system of signs which offer unexplored formal and conceptual structures, which have been repressed until now. The novelty and unknown dimension which I must face up to make me think I am moving towards a terrain that is richer in potential than those that are now overly familiar to me, namely representation and abstraction.

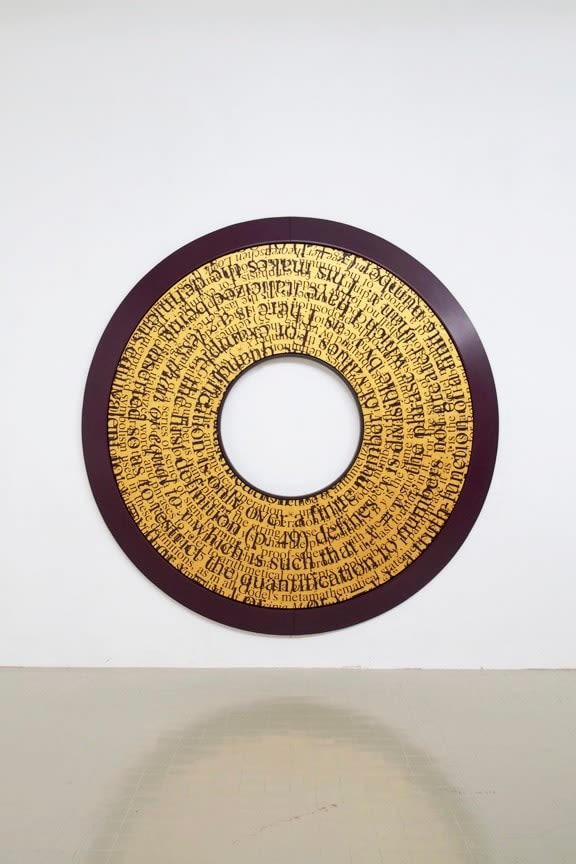

Gold Round with “Quantification”. 2012. Acrylic on canvas. Dia.: 243 cm

The world of mathematics interests me, since I find in it an original language, that of the symbols and formal structures which characterise a succession of equations. It involves a visual statement very different from all those that have been previously used, and by adopting this potentially rich language, I am currently attempting to develop a body of work that finds its own identity.

Our reactions when we face the symbols and visual representations of mathematics are highly subjective. To see them as beautiful, one needs to have a fairly pronounced taste for a cold non-expressive aesthetic. Again, one must adapt oneself to these new statements. Their formal interest is not obvious straightaway. We are so conditioned by the approach we once had towards them when we were studying at school that it is difficult for us to appreciate their aesthetic value when we rediscover them in a space allotted to art.

It’s true that there is a mathematical beauty, which is akin to the beauty of poetry. It comes from the immediate simplicity, from the purity of a formula reduced to four symbols that are perfectly articulated, as in Einstein’s E=mc2, and through which one of the fundamental laws of the universe is encapsulated. In my work, I am considerably fascinated by the richness of content and the economy of means of the equations I choose. I’m often inclined to think that each painting is a kind of equation, that it can be considered a masterpiece when it achieves the perfect synthesis between the idea and a formal solution, when there is no flaw in the direct relation sustained between the pictorial and the concept. But in fact, and I repeat, what interests me here is to open up as much as possible the artistic field to new, visually original statements.

Now, within this language, why do I choose this figure rather than another?

Let’s say I am drawn by what creates the greatest difference from what I am accustomed to. I don’t choose, for example, figures which resemble, if only slightly, geometrical paintings we have seen in the past. What interests me is their radical newness, their difference, and, of course, the conceptual consequences that necessarily arise from them.

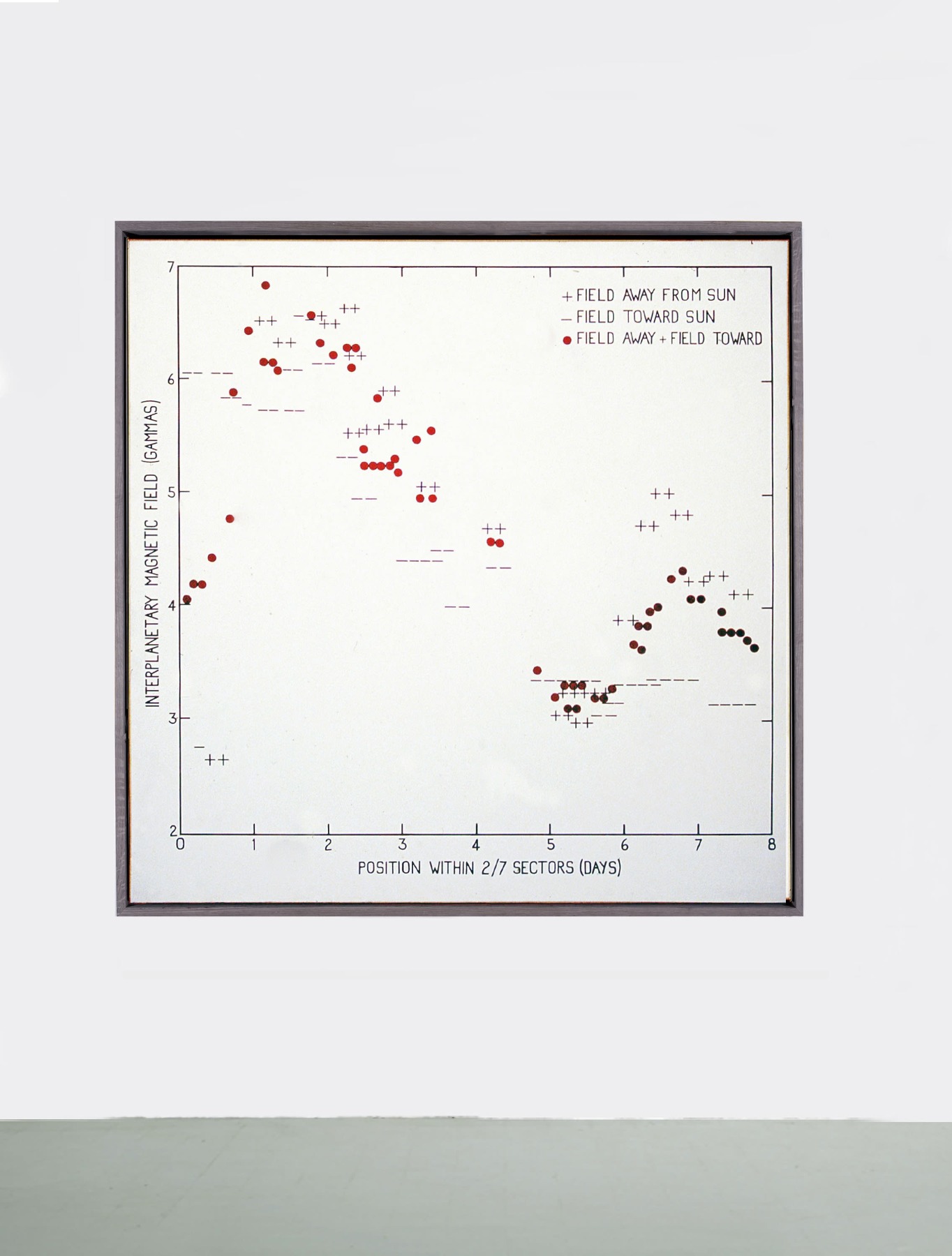

Magnetic Storms

and Associated Phenomena. 1967. Acrylic on canvas. 180x180 cm. Photo: Jerome Cavaliere

You have created works devoted to the so-called incompleteness theorems of the Austrian logician Kurt Gödel, whom you describe as “the most intelligent and most abstract mind that ever existed on earth.” His two theorems were the first to explore the limitations of formal systems, stating that in any reasonable mathematical system, there will always be true statements that cannot be proven. There are so many things we cannot prove, only experience. What is the role of experience in your work?

I fear I can’t offer any satisfying answers to your questions because you see in me perhaps a scientist or a philosopher of science. But I can tell you this, that clearly, I chose an artistic path where the rational predominates. That is a reaction in me to the abuses of Expressionism when it was enough for an artist to do whatever fantasy crossed their mind in order to pretend they were making art.

What interests me in what I am currently doing is the degree of abstraction of the symbols and equations that are presented, a degree of abstraction that has nothing to do with what is understood when one speaks of abstract painting or sculpture.

To reduce the world to mathematical formulae or even – why not? – a single formula, that was the ambition of Stephen Hawking and has been of other leading physicists. It is in itself a fascinating objective. In scientific terms, it would be a colossal advance, but is it conceivable? And how long would it be before it was deemed incomplete, if not false? We know all too well the limits of all those grand theories which have subsequently been shown to retain their validity in a certain context while losing it in a wider one. It is important to understand the limits of everything that we are given to think. As far back as 1930, the mathematician Kurt Gödel sowed the seeds of doubt within the scientific community by rigorously demonstrating that from logical sequence to logical sequence, reason inevitably led to disaster, since sooner or later it would end up deducing two completely contradictory theorems. Such as stating, for example, that the same object is simultaneously wholly black and wholly white. If science now accepts that its knowledge is relative, the first lesson that can be drawn from this, in relation to what concerns us as artists, is that we must recognise the relativity and limits of our ideas, their restricted and temporal nature. We must understand that ideas most opposed to our own belong to the domain of the possible. The history of contemporary art should be seen as a place of numerous lines of development, a firework display of divergent directions.

We know there is nothing we have a total understanding of. Taking upon yourself the aim of knowing everything about a particular subject or phenomenon is a utopia, an unrealisable goal. My fascination with these equations and figures, whose mathematical meaning I do not grasp, derives partly from the fact that they are already so loaded with meaning in their own context. Aren’t they the outcome of the most complex abstract reasoning that the human mind is currently capable of? Is it necessary to point out that it is not a matter for me of performing elementary scientism? It is not my intention to glorify science and to substitute its discoveries for the biblical themes or religious scenes that provided inspiration to artists for so long. With Matisse, it is not hard to conclude that the choice of his subjects was merely a pretext for painting. This does not prevent them from having maintained a false account of the origins or history of humanity. It is important to avoid falling into that kind of ideological trap.

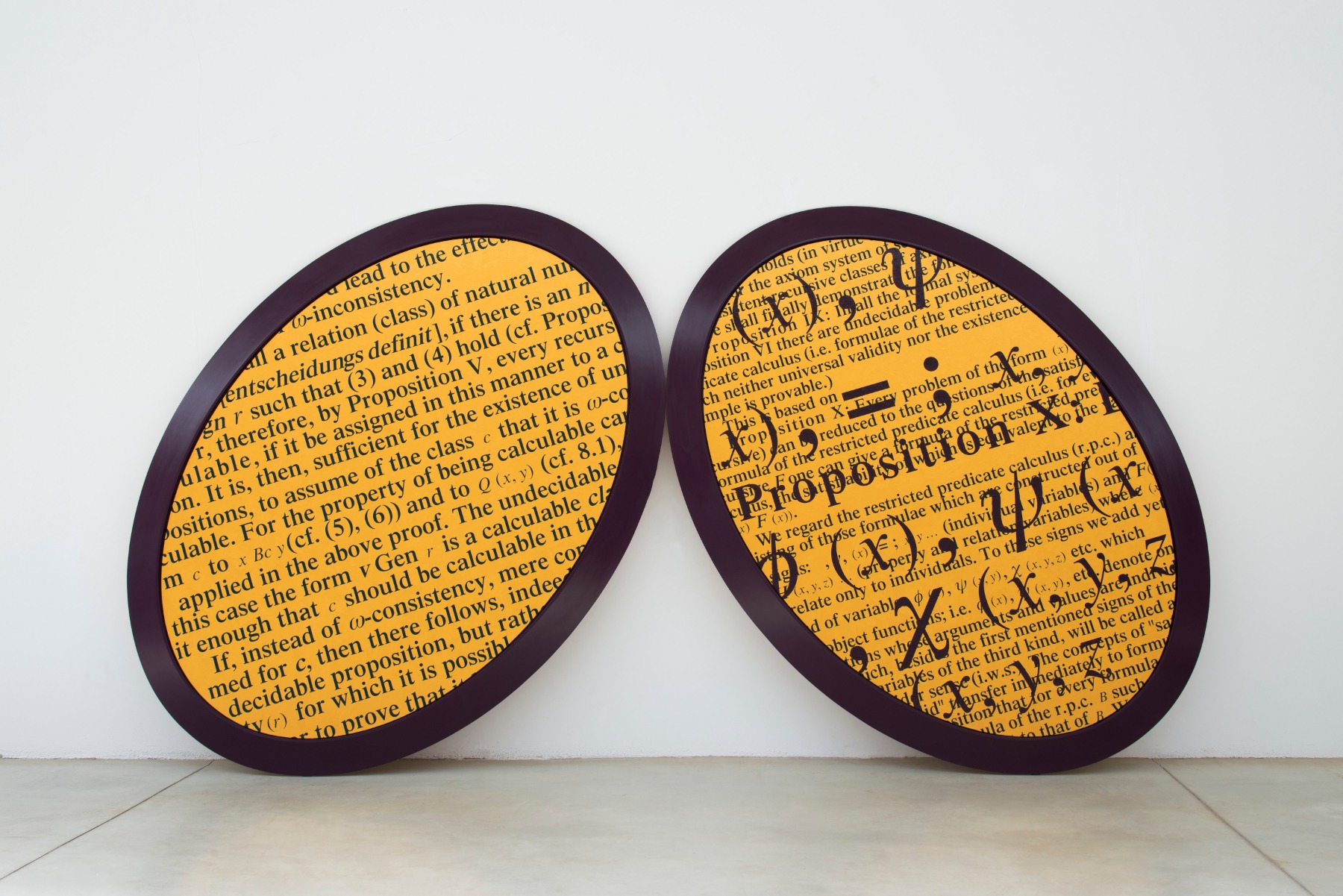

Two Gold Ovals with “Proposition X”. 2014. Acrylic on canvas. 243x438 cm. Photo: Jerome Cavaliere

There was a period in your life when you organized a series of performative readings by professors of philosophy and mathematicians. Can we say that your work reminds us of the importance of reuniting the exact and human sciences?

The theme of saturation has always interested me. When I was very young, I read a book by Abraham Moles on information theory, which developed that theme of saturation. He defended the idea that an excess of simultaneous information kills information. Noise theory lay at the heart of the subject he was exploring. I was thinking about this concept of saturation and how it might be taken into account in making art. In 1968, at the Judson Church Theater in New York, I put together a performance that featured three scientists giving at the same time three extremely specialized lectures at the blackboard. Later, I applied the saturation principle to literature, sound compositions, poetry, photography, video, and more recently my paintings.

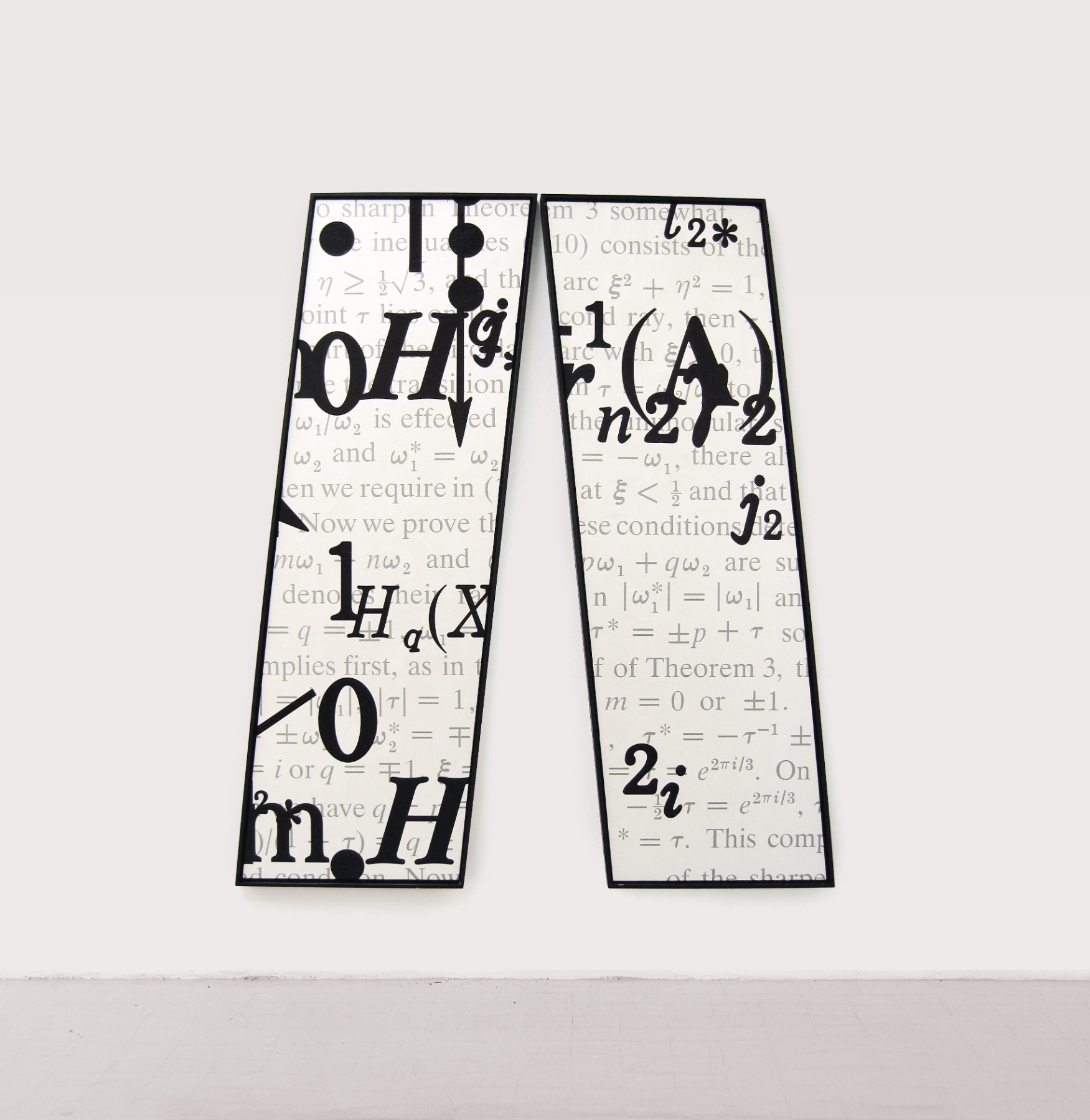

Pearl Saturation with 2 H and (A). 2009. Acrylic on canvas. 215x184 cm

What is your relationship with color? Your paintings often feature colored backgrounds. How do you approach color in your work?

The paintings from “Diffeomorphism” series captivate the viewer’s gaze, twisting it, throwing them into a labyrinth where one becomes lost in the text, seemingly without beginning or end. What kind of space do your paintings, which twist and curve two-dimensional space, inhabit?

Recently, since about 2000, I’ve gone back to this kind of work [my mathematical paintings] in drawing from scientific books. In this literature I found a great wealth of formal iconography that, for me, considerably enriched the known visual field.

This led to a further broadening out in my practice, this time much freer and less theoretical, what I call the Saturations, which are also on view in my show at the Riga Bourse. Working on gold or copper or other backgrounds, I very freely mix all kinds of equations and mathematical symbols to make pieces that are totally impossible to read. Instead, they are “texts meant to be seen.”

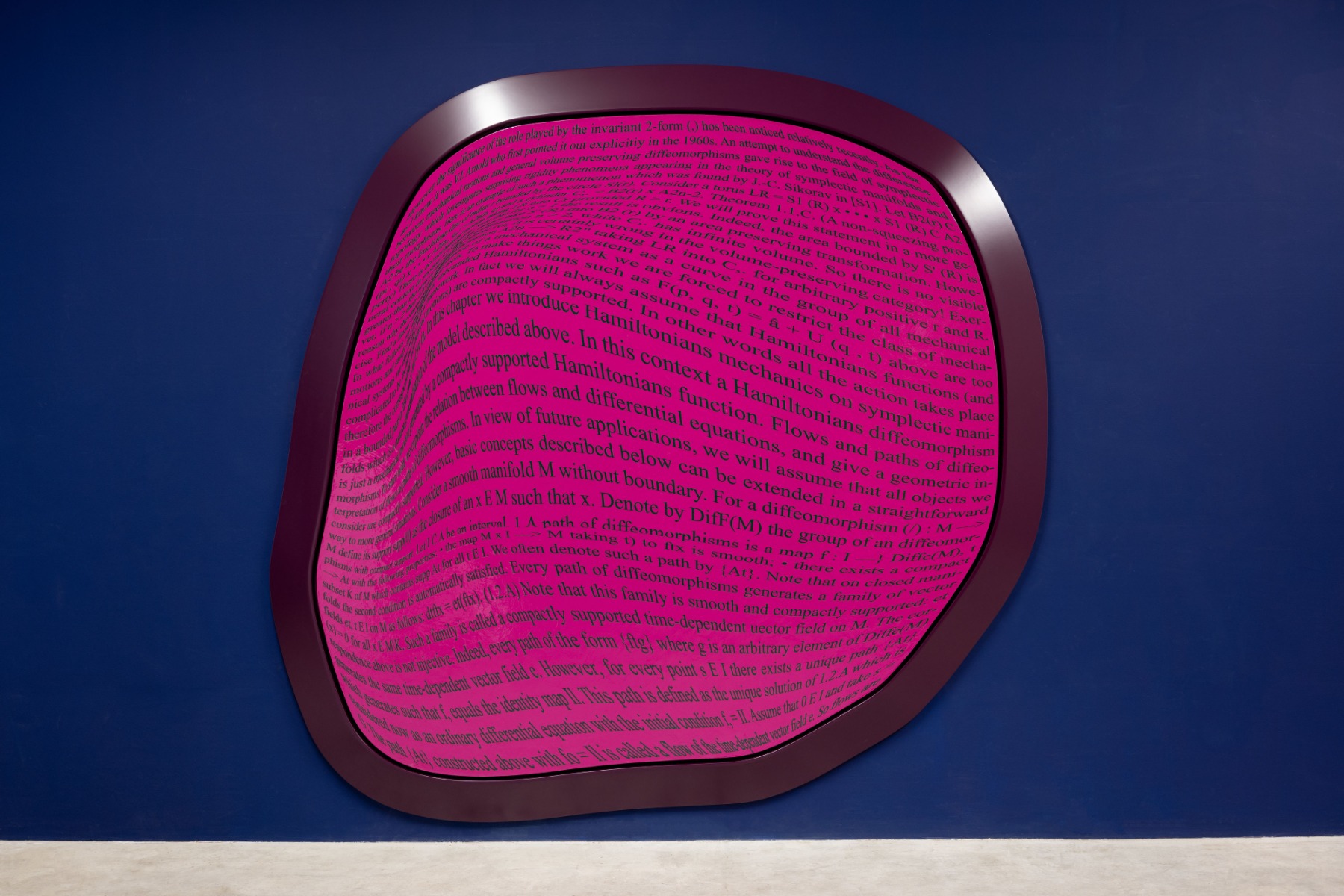

In another recent series, Diffeomorphisms, I digitally distort complex scientific texts to further disrupt their legibility and creating a sense of confusion that contrasts with the logic of the reproduced formulas.

Difféo Red 1. 2022. Acrylic on canvas. 247x236 cm

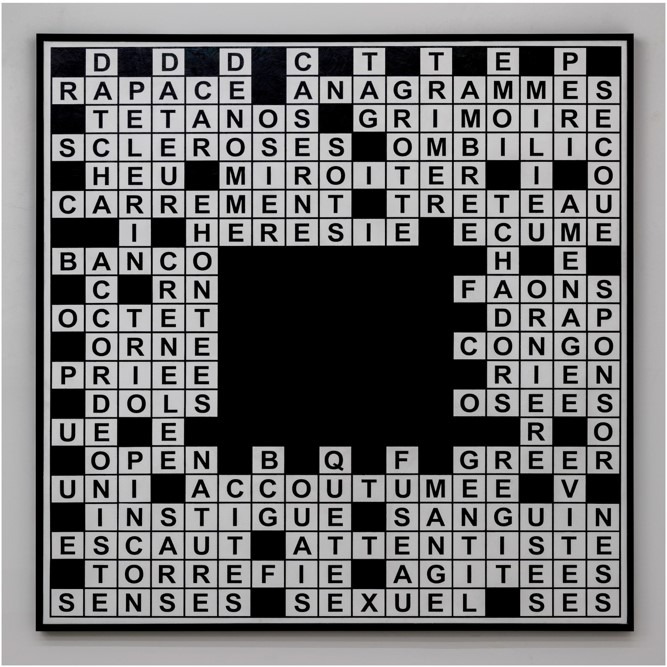

I know you have a painting that pays homage to Malevich’s famous Black Square. What does the black square symbolize for you?

Homage to Malevich’s

Black Square. 2018. Acrylic on canvas. 189x189 cm

One day I discovered this image in a magazine, and I immediately thought of Kasimir Malevich’s ‘Black Square on White Background’.

I asked myself the question, whether the author of this crossword or the original was aware of his actions. I decided, with a smile, to keep track of it, to make it my own, and to make it a tribute to this very serious giant, above even the greatest, of the 20th century.

Bernar Venet in his studio,

working on a Tar, Nice, France. 1963. Photo: Gilles Raysse

In the early days of your oeuvre, you exhibited a pile of coal, placing it directly on the gallery floor. What were you trying to convey with this gesture? Is it possible to find traces of this in your art today?

My taste at the time [1961] leaned to the color black and I was looking for an original solution to producing artworks that would be different from those by Soulages and artists who were working in an expressionist or lyrical vein. The use of tar and the idea of spills and runs seemed to me to be the direction to go in. That is how I came to produce my first Déchets [Scraps] pieces, which were done using old cardboard shipping boxes salvaged from trashcans on which I poured industrial oil paint. I also used tar, which I found at the village’s Highways Department, pouring it on sheets of paper; and to avoid any “controlled” composition, I would distribute it very spontaneously and vigorously using my feet. In this way I got formal arrangements that were totally unexpected.

Chance was the master of the game as well as the outcome.

On January 27, 1963, I wrote in my diary, “Black and black and black and black and black and black…” the start of a poetic text whose character, repetitive, monotone, and unlimited in time (it could go on for hours…), linked up with the monochrome reality of my “tar” paintings. The poem is also akin to the noncomposition of my Pile of Coal sculpture and seems to describe the black pages that repeat in my black book, all of them perfectly alike.

To turn to different disciplines to express myself seems natural to me and much more promising than limiting myself to only painting pictures. That was the moment I became aware of the idea of “equivalence” that has allowed me to develop my work from an original “conceptual matrix.” This principal has allowed me to considerably enrich the conceptual and formal dimension of my practice.

One of the most radical events happened one day when I left my studio temporarily because of the odor of tar that was poisoning me and went for a walk towards the Promenade des Anglais. While I was going along the sidewalk of Avenue Albert 1er, I discovered a site where roadwork had been done. There lay a pile of gravel mixed with tar. After the first shock of the tar spill discovered when I was in the army, this was my second important one. Whereas I had just left my studio whose walls were taken over by paintings covered in tar, that is, works in two dimensions, I discovered there on that sidewalk the exact equivalent but in three dimensions. In other words, what could have been considered a piece of sculpture. There are photos attesting to that moment, which I consider capital for a large part of all the works that followed. I am speaking mainly of everything having to do with the self-referential, horizontality, and chance.

The Pile of Coal follows up on that discovery. It corresponds to the principle embodied by that pile of gravel mixed with tar (the notion of pile, the color black, and malleability). I could then offer a piece of sculpture that obeyed new principles – including horizontality but especially the fact that it didn’t have a specific shape. That artwork became a concept and could be, by its definition, installed by anyone anywhere with different volumes and in several different places at one and the same time.

Related to: “Parametric Ordinary Differential Equation of the First Order in Two Dimensions”. 2000. Acrylic on canvas. 203.2x269.2 cm

‘Disorder,’ ‘chance,’ ‘entropy,’ and ‘tension’ are words often used to describe your work. What do these words or concepts mean to you?

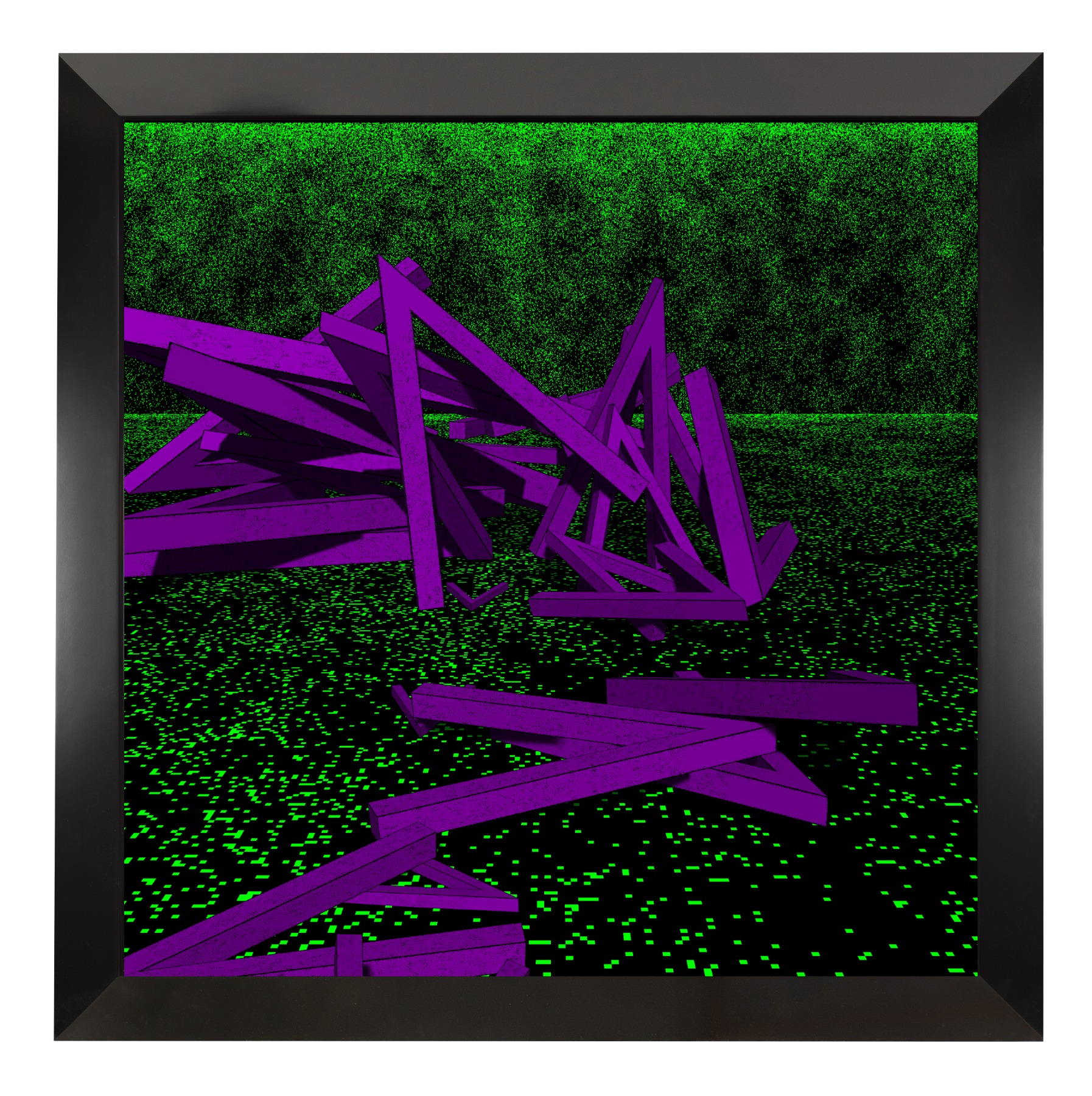

The idea of the mathematically undetermined first appeared in my work in 1979 in the form of a wood relief covered with graphite, which I referred to as an Indeterminate Line. It is a particularly representative piece in my sculptural work, and exemplifies a key moment, a pivotal moment, when I was able to free myself from the constraints of geometry.

These “Indeterminate Lines”, no longer regulated by the rules of geometry, immediately represented, for me, an opening full of formal and conceptual possibilities. Actually, concepts such as Disorder, Instability and Dispersion are derivatives of the “Indeterminate Line”. After that, this new orientation allowed me to introduce what I call “Accidents” and “Collapses,” which I now consider the most fecund and innovative direction in my sculptural production. These works have made it possible for me to put forward formal configurations arising from new practices, such as Incertitude, Entropy and the Unexpected, which became core concepts in my work.

For me this was an ideal solution to the problem of how abstract sculpture could be emancipated from traditional Constructivist composition or the serial forms of organization practiced by the Minimalist artists.

Exhibition view: Seoul Museum of Art (SOMA),

Seoul, South Korea. 2011. Photo: Jerome Cavaliere

Speaking of new fields of investigation, you mentioned that one of them is generative art. What fascinates you most about generative art? Is it the interplay of chance and unpredictability, and the infinite number of possibilities?

Approaching the pieces as visual sculpture based on complex computer coding, these works are digital paintings of images generated by an algorithm. These paintings were produced, framed, and hung in the gallery Perrotin’s space in Paris, and I did not participate in their making or even see the physical exhibition. In this project, the algorithm helped to create an infinity of formal possibilities and unexpected configurations that correspond conceptually to my latest large sculptures.

Generative Angles Painting – Purple 5. 2024. Acrylic on canvas with UV ink. 178.5x178.5 cm. Photo: Archives Bernar Venet

You have always been fascinated by what you do not understand. For many people, the notion that they do not understand something causes them to turn away from it. In your case, it is quite the opposite—lack of understanding becomes a limitless source of creativity. Is it important to you to understand?

Like a scientist whose only activity is research, I try to conceptualize unique ideas in the field of art, conceptions that seemed inconceivable until now.

***

Bernar Venet: Painting: From Rational to Virtual, 1966–2024, a retrospective of the works by the pioneering French Conceptual artist Bernar Venet, will be on view at the Art Museum Riga Bourse from January 25 to April 27, 2025.

The exhibition is supported by Bentley Riga, the University of Latvia, Dūrmuiža, COBALT Legal, Malvīne, the Investment and Tourism Agency of Riga, the Embassy of France, and the French Institute in Latvia.

Title image: Bernar Venet. Photo: Courtesy of the artist