Of People and Things of the Frontier

An interview with Lithuanian writer and artist Gabija Grušaitė about her project Ferma which took place on 7-th of August in the eldership of Sariai

We leave the Vilnius Contemporary Art Centre in several buses, facing about an hour’s journey ahead. We move ever closer to the Belarusian border, and eventually arrive at the small settlement of Sariai. “We’re now just two kilometres from the border,” says Justas Janauskas, a quietly dressed, calm young man of about thirty, wearing glasses. Justas is one of the leading figures of Lithuania’s generation of digital entrepreneurs; he is the co-founder of Vinted, a successful online marketplace. He is also the partner and supporter of Lithuanian artist Gabija Grušaitė’s projects and shares her ideas.

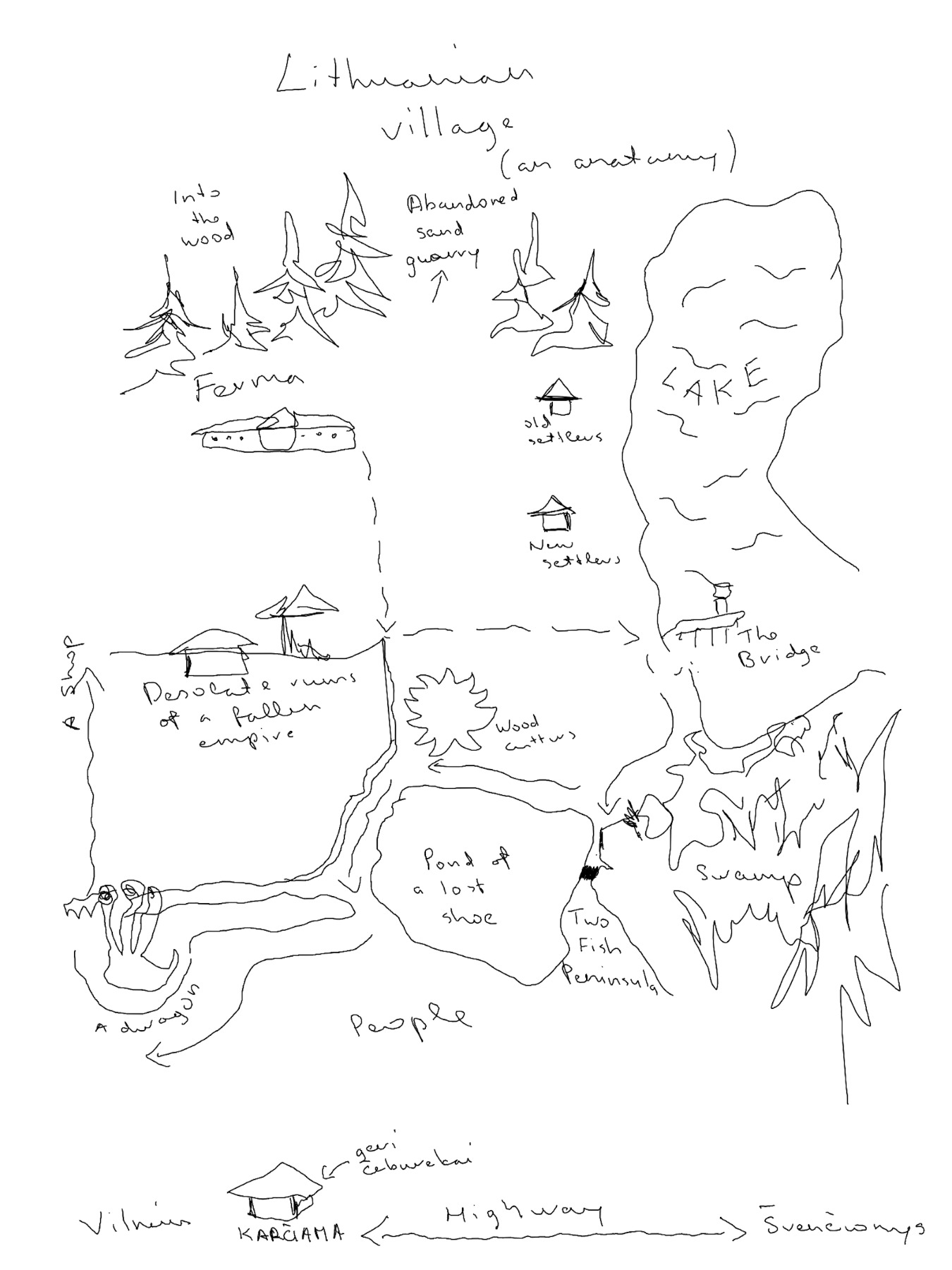

Gabija Grusaite. Sariai Map

Gabija first became known in Lithuania, and more recently beyond its borders, primarily as a writer and the author of three novels. In recent years, however, she has returned to her artistic roots and is now realising herself as a visual artist — though in her visual projects, text still plays a central role. Gabija comes from an artistic family: her father is the well-known Lithuanian sculptor Marius Grušas, and her grandfather was a painter who began with colour abstractions but later shifted towards realistic portraiture.

Ferma. Installation view. Photo: Jonas Balsevicius

It is important to talk about her family because, on these several buses, we — the artists, curators, and art critics from the Baltics, Finland, Poland, and beyond, invited to this project — are also travelling into the very heart of Gabija’s family history. Sariai is the place where she spent every summer as a child. When we arrive at the farm building (in the collective farm era, an entire herd of cows was kept here), we first enter a small room with bare concrete walls. There is nothing on them — only on the floor Gabija Grušaitė has drawn a kind of map-diagram of her world back then and how she perceived it. Here, we are greeted by two Italians from the curatorial duo Francesco Urbano Ragazzi, who assisted Gabija with this project. They had previously worked extensively and fruitfully with Jonas Mekas and his legacy — from publishing books to organising exhibitions. They say little, and simply invite us to embark on a journey into the “world of the frontier.”

Curatorial duo Francesco Urbano Ragazzi intruducing the exhibition with artist Gabija Grušaitė

And then we step into the vast space of the former farm, which covers 1,500 square meters. Almost everyone’s lips involuntarily form an unrestrained “wow!” The entire space is filled with objects arranged in several “storeys” — tools, metal scraps and constructions, fragments of various materials, wheels, machinery. Between these piles, laid out like a network of narrow “streets,” you can actually walk. Then, around the next turn, a tractor comes into view, parked here forever. A little further on, there is an old Soviet car, its surface thickly covered with clumps of compacted dust, the same dust coating its Soviet-era license plate: “50-18 лиу.” If you walk further, you’ll come upon a dark blue Ford from the 1980s, also dusted over, this one with a Lithuanian plate. Between all this are fragments or sketches of sculptures, paintings, drawings, award cups from art competitions, and stacks of empty frames. It feels like a kind of museum of everything — one that welcomes within its walls all traces of human material activity without distinction, with the same all-embracing curiosity.

Ferma. Installation view. Photo: Jonas Balsevicius

“This space is simply every Eastern European dad’s dream,” my colleague, the Polish journalist Emilia, tells me. And indeed — this space, a grand workshop and warehouse rolled into one, truly encompasses the world of Gabija’s father, Marius Grušas, the creator of one of the most famous artworks adorning a courtyard in Old Vilnius — “Medeinė: a sculpture depicting a woman who, with graceful composure, sits on the back of a bear. She is the Lithuanian goddess of forests and hunting. Making her way through the streets of Vilnius’ Old Town, she reminds the city that it was once a forest, and still is. Everything is a forest. Even Marius Grušas’ fortress. And this fortress, like the forest, cannot be owned. No one possesses it, because everyone is possessed. The master of this fortress is a subject of an empire that no longer exists, or of the fear that an empire might return to take everything away,” write Francesco Urbano Ragazzi in their curatorial foreword.

Ferma. Installation view. Photo: Jonas Balsevicius

At both ends of this vast workshop-warehouse, screens are installed, projecting Gabija’s video work — the same farm, her father engrossed in his work, the surrounding landscape, all filmed in winter with snow blanketing the ground. There is a sense of cold and a certain crystalline clarity, characteristic of winter and the white-grey, white-brown palette. Gabija’s voice translates this sensation into words. She speaks of how she once hated this place, felt constrained by it, and longed to escape. "Only as the war of my generation draws closer and the sound of drones enters the nightmares can I finally understand what it means to come from the frontier, a place where social tectonic plates move first… I move as a stork, but frontier is printed in the blood. It is not safe here. But we still grow. Animals, plants, people of the frontier."

This is the feeling, the state of mind that all of us living in the Baltic countries seem to reflect upon. It’s as if we live on the edge, building defensive ramparts out of our lives, surrounding ourselves with fortresses of family hearths and walls of happy moments. How fragile — or, conversely, insurmountable — are they? I believe this is partly what Gabija’s project seeks to tell us. Open to the public in the best FLUXUS tradition for just one day, it nevertheless holds the potential to continue into the future. It speaks of this strange place, erected in honour of the idea of the socialist farm, which now, in capitalist times, is filled with memory and material traces like a capsule sent into the vast night of time.

This is what I wanted to talk about with Gabija Grušaitė, a slender, graceful woman with a voice capable of gently and confidently “putting everything in order.” But we actually began our conversation with completely different topics.

Gabija Grusaite, Ferma [still]. Courtesy of the artist

I have to say that I’m a poet myself, but I also work with a collective of multimedia artists. In a way, I’m migrating from one medium to another. That’s why I find your development in both the literary field and the visual arts so interesting. As I understand it, though, visual arts were actually your first area of interest.

Yes, I went to the Čiurlionis School of Art — a very academic training school where, you know, you draw the plaster casts of heads and study the fundamentals. A lot of Lithuanian artists, like Augustus Serapinas and Emilija Škarnulytė, went to the same school, which is how we know each other. It’s also the school my father and mother graduated from.

I really wanted to make art from a very early age, but within the school environment, I wasn’t really accepted. I would often get remarks from teachers saying I wasn’t very talented, simply because I wasn’t interested in the realistic representation of objects. I think even then, I was already more drawn to cinematic storytelling and feelings. So, in that environment, I felt quite discouraged.

And when I graduated from school, I was young and hot-headed. So I thought, “Screw art, I’m going to be a writer.”(Both laugh.) I was 18 — the age for exactly those kinds of decisions. I think I still wanted to make art, but at the time I didn’t have the language to express what was inside me, and I couldn’t find people who could help me understand it.

So literature seemed easier for me, in a way, because I could work alone — I had much more control than I did in art. In art you need to collaborate, you need to present it, you need a space. But with a book, you can work alone for many years until it’s ready for someone to read. And then it becomes a different process entirely.

Photo: Vismante Ruzgaite

So it’s about having full control.

I think I needed that control at that point in my life, so I decided not to pursue an art education. Instead, I went to study anthropology at Goldsmiths. Looking back, it was a rather childish move — I thought, “OK, I want to write books, and to do that I don’t want to study literature, because that would just mean studying what other people have written, which won’t help me all.” Anthropology, on the other hand, promised a method for observing people and understanding contemporary culture. From that point on, I became interested in the “contemporary” — in what’s happening now, in trying to understand it.

So I went to Goldsmiths and studied anthropology and media, and I think that really shaped the way I engage with the world. Then I wrote my first book (Neišsipildyma, published in 2010 — author’s note) quite young — I was 22 when it was published, but I wrote it when I was 19 or 20. I think that book defined my relationship with literature for a long time. I was really obsessed with learning how to control the narrative and create worlds that people could enter. At some point, I realized that I conduct very extensive research for each of my three novels — it usually takes me about seven years.

I gathered a lot of material — visual research, scientific studies — for “The Mycelium Dream” (published in Lithuania in 2023, both English and Latvian translations are on their way to the audience — author’s note). I did extensive work on epigenetics and neuroscience, and I really felt the need to communicate those ideas as well.

And of course, language is an amazing tool — you can do so much with it. But there’s also a part of it that can be limited in a way. With this project, with Ferma, I’m trying to communicate something beyond words. From my perspective, it’s not about doing either literature or visual arts as separate things. It’s more that I’m interested in certain topics of research, and the final result might be a book, a film, or an object — but it all comes from the same realm of exploration.

But as far as I know, you’ve also had experience curating at a gallery in Penang, Malaysia.

I would say my role was really multifaceted because I was also the director, and a lot of my time went into fundraising. We didn’t receive any funding from the state, as the Malaysian art funding structure is almost non-existent. So, I spent a lot of time fundraising, and honestly, I didn’t have as much time to focus on curating as I would have liked. After a while, I realized that maybe this wasn’t my true calling. But I’m glad I did it. I’m grateful for the experience — starting an art institution from scratch was an amazing journey.

Does this independent art space Hin Bus Depot still exist?

Yes, it’s still operating, and we maintain a relationship. Whenever I have the opportunity, I try to visit once a year to see friends. Penang remains a really important place in my life. The direction of the space is quite different from when I was there, but they continue to run a very interesting program, mostly for Malaysian and Southeast Asian artists. I’m really happy for them.

So, why Malaysia? Was it basically because it was ‘as far away as possible’?

I think so, yeah. Of course, I wasn’t very conscious of it at the time, but I think I wanted to escape certain things. Intuitively, I knew I was limited by my own ideas. And when I graduated from Goldsmiths, Lehman Brothers collapsed, and there were no jobs whatsoever for recent graduates.

At that time, I had just published my first book, so I had very little money and needed to make it last. The plan was to go to Bangkok and start writing my second book. I know how that sounds — kind of naive — but that was me at 22. I actually went to Penang just for a weekend because I had some friends from London who were originally from Malaysia, and I really liked the place. There was something very appealing about it, especially since it used to be a British colonial island, similar to how Singapore and Hong Kong function. So, it's very different from the mainland Malaysia.

I was really fascinated. What happened was that I came for two days, but I ended up staying a week, then two weeks, then a month. Next thing — I had some projects: I used to do copywriting for a local cultural festival there. Next thing — I had dogs, a house, everything. So in a way, it wasn’t a planned decision to live in Penang — it just clicked. I found friends easily and felt really safe and accepted in the community, even though most of the time I was the only white girl. I think Penang allowed me to see myself differently and reflect on a lot of belief systems I had embedded in me from growing up Lithuanian.

In Lithuania, one of the survival mechanisms and ways of defending against trauma is perfectionism. It’s so deeply ingrained in me that only when I stepped into the Malaysian community did I begin to realise that it’s not the norm — it’s a distinctly Baltic thing. Perhaps in Latvia it’s similar: this idea of not allowing yourself to make mistakes as a survival strategy. Then I looked at my friends, all high achievers working crazy hours. Being in the Malaysian context made me see that this is a cultural pattern. For a while, I couldn’t fully grasp it, but having that distance from Lithuania completely changed the way I see my own culture and the Baltic region as a whole.

When my second book (Stasys Šaltoka: vienerei metai published in Lithuania in 2017 and translated as Cold East and published in English in 2018) came out, I think it was a study on Lithuanian identity and the dreams of escaping. But I wanted to write a book about dissociation without ever using the word “association.” It was a very difficult task to create a character who doesn’t allow himself to reflect on things. That’s what fascinated me about Lithuanian identity — the kind of surface tension where everything feels like it’s about to burst, but hasn’t yet. You sense the tension, but you don’t quite know what kind it is. I was really interested in that. And I think Cold East encapsulates my Malaysian experiences and how they transformed me completely as a person.

It seems that if Penang was ‘as far as possible,’ then Sariai is ‘as close as possible’ to your origins.

My father bought the farm when I was little. Essentially, I lived in Vilnius, but my summers were always spent there. It was a source of conflict between me and my father because, as a teenager, I wasn’t fascinated by that place at all. I think there was an element of shame — the vastness, the overwhelming feeling, and the emotions the place communicates. Only now, as an adult, do I realize that my father was creating something special. I think that space was almost like his practice — a large-scale sculpture he was shaping.

But being there as a child was really intense. I was trying to protect myself from that intensity, kind of like putting up a shield. Only now, as an adult, do I have enough emotional distance to explore that space and try to understand my father. Before, I was even judging him. I found myself making excuses for him or trying to change him — typical family dynamics.

Once I stepped aside from those feelings and judgments, I was able to see it with completely new eyes — and that’s when it happened. This film was created during my first year at the Royal College. I was really interested in the Baltic frontier identity. And I realised that if I wanted to really dig deep into that topic, I had to start with myself. What makes me the way I am? And the answer was the farm, my father, and our relationship.

But I also wanted to keep that line that it’s not really autobiographical — it’s more of a departure point for a broader, more universal human experience. In a way, I think almost everyone in families has a hoarder, one way or another.

But also these childhood experiences — and the way they shape us — raise the fundamental question: what are we inheriting from the land and from our culture? So that that brought me to the farm and also the post-soviet heritage.

Marius Grušas, Gabija's father, talks with visitors. Photo: Vismante Ruzgaite

But was this farm accumulating these things and emotions layer by layer, or was it already quite full of them from the start?

You know, even from the start it was intense. I don’t really have memories of it myself, but my dad said the most intense moment was when the cows started to die. Before, he only had that small annex of the building he was renting, while the main area still had the cows. Then, with independence, there was suddenly no infrastructure to care for the cows anymore, so they all died. I think that from the very beginning, the space carried a huge emotional charge.

And from the beginning, it wasn’t like it is now, because he kept bringing in new things. But it was already starting to become this huge place with a vast space, and he kept changing it over time. He reorganises, he rearranges, he moves things. It's like a very ongoing, involved process.

Ferma. Installation view. Photo: Jonas Balsevicius

It’s also interesting that part of this space is occupied by belongings of your grandfather, who was a painter. This heritage feels completely different — more subtle and refined. Some small sculptures, some books, some drawings.

It’s multi-generational, which I think makes it even more complex in a way. I was very close with my grandfather before he passed away. He was an incredibly charismatic man and did many projects that truly inspired me.

For example, up until the year he died, he was conducting art classes for prison inmates—those who were basically serving life sentences. He did this for many years as one of his meaningful activities. Nowadays, many people might join a project for just two weeks or so, but he showed real consistency and commitment. He was genuinely there, offering non-judgmental support to these people for many years. In many ways, he was really ahead of his time. There was always a very deep connection between us because my grandfather was the only family member who read my books and commented on them at length. He would say things like, “This is a very good idea,” or “This I don’t like.” So we had those conversations, and now when I see all his life’s work stored there, it brings a lot of healing for me as well. Sometimes I feel like I’d like to take it away and store it properly, but that would require a conversation with my dad — and at the moment, I’m not ready for that.

So yeah, it's there's — like a very different layers of family. Family as interhuman complexity. It’s about how our lives are connected to objects, how we leave things behind after we pass away, how we attach meaning to them, and how we accumulate objects in an attempt to hold on to time in one place and not let go. So in a sense, Ferma is really engaging with objects in a deep way — showing how they can become extensions of the human body and psyche.

Ferma. Installation view. Photo: Jonas Balsevicius

In your video work, which we saw at Ferma, you return to this place in winter — with snow and cold. Why not summer?

There’s a lot of beauty in winter. It’s a time when everything is dormant, waiting for spring to blossom. For me, winter is the best season for reflection. Summer, perhaps, is the time for action and experience, while winter — with its low, quiet energy — lets you see things more clearly. For instance, you can see the landscape in its bare form, while in summer it’s hidden beneath leaves. I felt that winter was actually the best time to experience the farm as it truly is, without any external charm.

And since I was also interested in the landscape, I included the surroundings of the farm. I chose winter as…

Almost black-and-white setup…

Exactly. It's very simple. I think with summer it could have been more romantic, and I didn't want that idyllic kind of connotation.

There’s also another layer to Ferma — the layer of the frontier. As Justas mentioned when we were driving here, the Belarusian border is actually only two or three kilometres away.

It's quite close, yes.

What do people who live here think about it?

Well, I know what my father thinks about it, and I know there is a sort of tension. For example, even if you go to pick mushrooms in the woods, you have to be careful. You don’t want to wander into certain areas where the border is too close, because they might think you’re a smuggler or something. There’s this very practical awareness of it.

But then I was thinking about the frontier — for me, it’s not a physical place. It’s more a kind of uncertainty that exists within the psyche. I notice this ‘frontier identity’ also in bigger cities, among people who have just arrived and haven’t yet built their networks. The way I see it, the frontier is like a tear in the social fabric. In the Baltic region, and perhaps in Finland as well, the close proximity to ongoing political tensions — and the possibility or even the imagination of aggression — also tears at society in a certain way. That fear also activates various survival mechanisms that are epigenetically embedded in our region.

For example, we had perfectly nice neighbours who seemed so decent. But when the tension began around 2023, they suddenly became very different people — suspicious, almost hostile. If someone left a car outside, they would aggressively insist that it be removed. Fear can unlock certain sides of people you never knew existed.

So, going back to that idea of the frontier — for me, frontier identity is that tear which allows both healing to take place and survival mechanisms to surface, where you can actually observe them. When I think about Israel and Palestine, I also see it as a certain kind of frontier — something that exists in other places too. I'm not tied to Baltics specifically, I see it more as an analysis of a condition that emerges in many contexts. Once, I did a project at the Mexican–US border, and it carried that same particular feeling — the way social and cultural fabrics are disrupted, and new cultural forms emerge in their place. Penang has a lot of that energy as well.

I’m just really interested in this — it’s a very anthropological way of looking at things: if you break something, what will emerge in that place, how things will form. It’s interesting to watch right now. There’s so much fear. I don’t know much about the Latvian context, but here fear dominates the public conversation. It’s about creating fortresses, denial, and all these different survival strategies.

Ferma. Installation view. Photo: Jonas Balsevicius

Fortress is also a subject in your work. But what kind of fortress is it? Is it a fortress where memories and fragile things are kept?

I’ve been reading a lot about the psychology and mechanics of hoarding, and one interesting thing I found is that, in a sense, hoarding is a defence mechanism against trauma — it’s a trauma response. Of course, there are varying degrees of it, but one of the key mechanisms is the inability to let go of anything.

So when you think about a fortress where time stops, and you’re defending yourself from emotional pain and the pain of loss by holding onto everything — by not allowing new life to come in because you’re so tied to the past and the present — it’s almost like creating a barrier between yourself and life through these objects.

It’s also interesting that in Chinese culture and Feng Shui, there are many teachings about hoarding and energy. For example, if someone has recently become single, it’s advised to clear out all the clutter, because the idea is that clutter blocks new things from entering your life.

I think there’s a lot of truth to that. When you think about the farm, it preserves so many things over time. When you enter, I really physically experience this sensation that time stops in that place. I also see it as a quest for immortality — you’re not letting go of anything, collecting your entire life as one huge whole. So, in a way, it’s a fortress against time, against emotional pain, and against change. There are many layers to it.

Gabija Grusaite, Ferma [still]. Courtesy of the artist

But there’s also something about the scale of human personality. In our everyday lives, we’re quite limited by our physical spaces, so we tend to keep our personalities fairly minimalistic. Here, though, it’s possible to see the size a personality could actually take.

Do you think all of us would be capable of filling a place like this?

Hmm, that's an interesting question!

My father is special because… I was talking to a friend yesterday, and she said everything is so photogenic because it’s not random how things are arranged. At least for me, it’s very beautiful the way he stacks all these piles. They look really eye-catching from many different angles.

There’s also a particular smell to this place — the feeling of time standing still and its scent. You know, the dust, the faint metallic smell in a way. I think it’s a very biotic space, at least for me. Whenever I go there, it really captures my mind and makes me start thinking about life and death. It’s impossible to be there and not reflect on these things. Somehow, the space evokes a deep response.

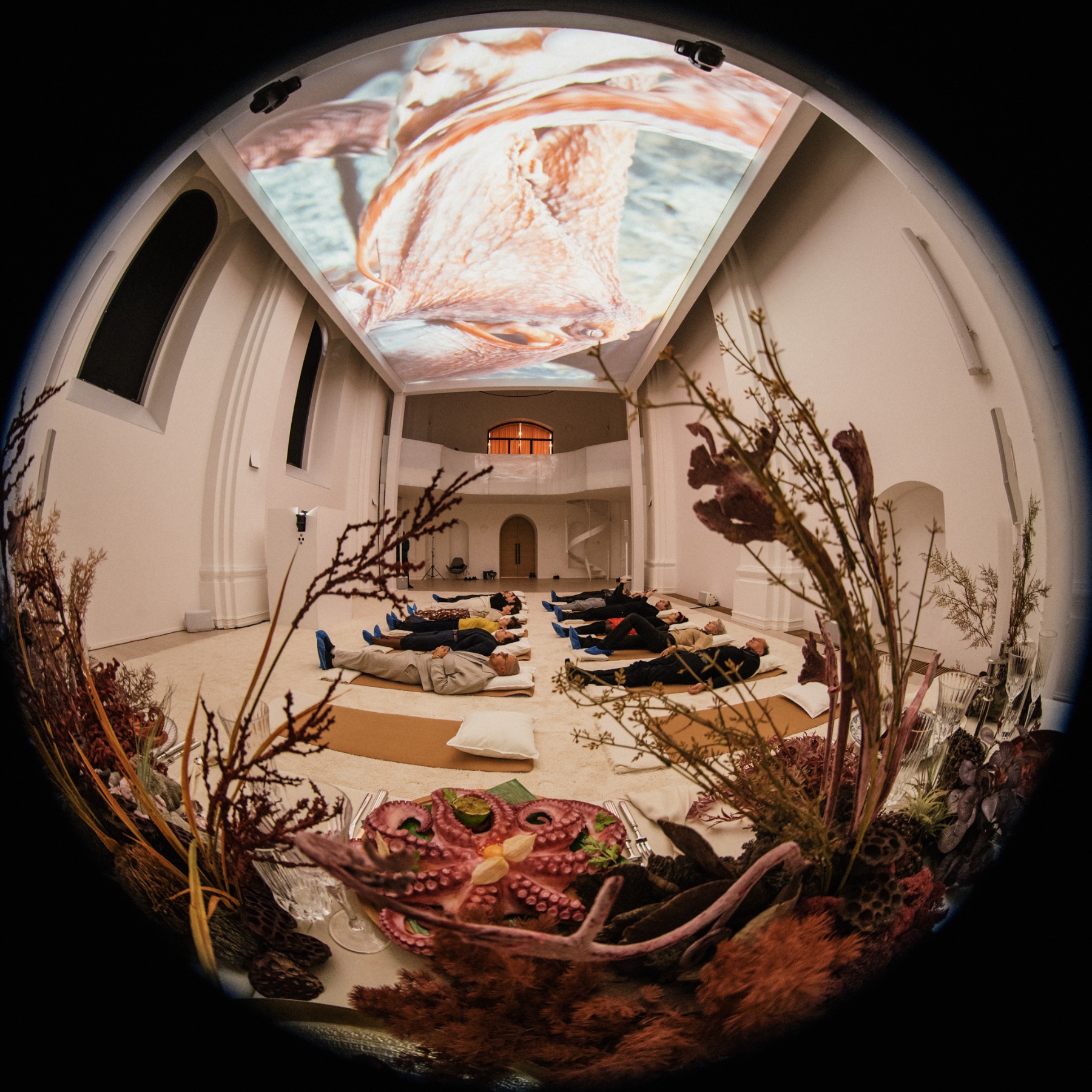

Date with an Octopus (2024) is an interdisciplinary audiovisual installation that expands the universe of the novel Fungal Dream by Gabija Grušaitė. Visitors are not only observers, but also participants. In the first part, the audience is invited to lie down, make themselves comfortable, relax and explore their body and consciousness. The blurred boundary between the inner human world and the external world is explored in relation to the Pacific octopus, which is both a concrete physical object/subject as it is a symbol and a fantasy

Last year at the Art Vilnius I also saw your work Date with an Octopus. And now I've seen your new work. Both works are very visual, but the text takes quite meaningful place. Is it maybe a new form of literature?

That's what I would like to think as well, I am very driven to experiment with spoken words.

I try to expand what the language can do in relationship to other mediums and other formats. And I was also interested in this bodily experience of both Date with an Octopus and Ferma. They also have this very physical experience to it, which I'm interested to explore. But yes, I think it's expanding literature and sort of blurring the boundaries of where visual art and literature merges into each other.

And I don't want to go too much into one or the other territory, I prefer kind of keep the tension between the two. And I think in the future, text will continue to be an important part of what I do.

It's kind of 3D literature?

Yeah, it's a good. I'll use that. It's a good way to describe it.

Ferma. Installation view. Photo: Jonas Balsevicius

But but what I'll also loved in this work, in Ferma, was this feeling of life on the frontier. A life full of fears sometimes. But there is also some kind of hope. Something that maybe we can bring to the world from the position of frontier, but what it could be?

I am hopeful. I'm not a cynical writer. There was sometimes in Lithuanian context maybe a misunderstanding of what I do, but I am hopeful in a lot of ways that this pain and this facing the reality, not running away, not being in denial actually can make us much stronger. And I believe actually, at least for the Baltic region, it's what makes us interesting and able to communicate outside.

And I've recently read this book by Oliver Moody. It's called Baltic: The Future of Europe. He was asking a similar question, but more from a political perspective — like, what do the Baltics have to teach the world? It was also about the courage to stand up, even when it feels discouraging.

Yesterday, I spoke with my friend from Uzbekistan, and she mentioned that the Baltics have been a guiding force in understanding the post-colonial context in her country. I truly believe that the Baltics play an important role as a frontier — in how people experience challenges and, ultimately, overcome them.

Ferma. Installation view. Photo: Jonas Balsevicius

Perhaps this “frontier uncertainty,” which you mentioned in your video work, also gives us a deeper sense of the present moment.

I believe in that too — the feeling of being truly alive, not living in some imaginary tomorrow. With this work, I also wanted to encourage letting go of the past in the same way. It’s a delicate matter, because in Vilnius, sometimes sometimes letting go can become a denial — as if one is pretending it never happened.

I think for me it’s more an invitation to face the past and actively let it go — not just be like, “OK, it never happened.” So, I believe that living in the moment, without being confined by the past or the future, is a really powerful experience — a moment where a lot can happen when you’re fully present.

What is it like in Latvia?

I think – kind of the same. Let’s just live today and hope for tomorrow.

Yes, for us it's more like we should spend time with friends, we should not prioritise work. It even affected how Justas has scaled down his work to spend more time with friends, with family, to support me and pursue his hobbies. Because it's a feeling that life is precious.

Every year is precious and you don't want to waste just working 16-hour days, which he did for much of his life. So, I think in a way it also can be catalyst for change.

Photo: Vismante Ruzgaite

What do you think — could there be a Step 2 for Ferma?

I haven’t defined any concrete plans yet, but I’m interested in traveling with these objects. My father keeps joking that when he dies, the farm will be mine, and he asks what I’m going to do with it. In many ways, that’s very true — but I wonder, can I take my share earlier? What can I do with it now?

I'm considering for these objects to travel — to change context — and I'm interested in what kind of stories they will tell in these different contexts when they are removed from the frontier identity. Do they carry their own frontier identity with them? Or will I be destroying it? There are a lot of options and strategies. I'm just interested in exploring where this could potentially go.