Justas Janauskas: “I am a big believer in laser focus”

An interview with tech entrepreneur and Founding Patron of the Upė Foundation

We met with Justas Janauskas in Riga on December 10, on the very day when the newly launched Upė Foundation, of which he is the Founding Patron, announced the open call for its first project. “Upė begins its work with a series of Curatorial Fellowships with major institutions – Southbank Centre’s Hayward Gallery, Tallinn Art Hall, and Camden Art Centre – aimed at supporting the next generation of curators across the UK and the Baltic countries. The inaugural 18-month Curatorial Fellowship Programme is conceived as an exchange between London and Tallinn. The first two open calls include one position at Tallinn Art Hall for UK-based curators and another placement at the Hayward Gallery for curators from Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia,” the press release notes.

Prior to that, we met in Lithuania, in the Sariai eldership near the Belarusian border, where last August Lithuanian artist and writer Gabija Grušaitė presented her one-day project Ferma, curated by the Italian duo Francesco Urbano Ragazzi. Gabija is Justas’s wife, and it was she who introduced him – a successful young entrepreneur from the tech world – to the vast and multilayered realm of contemporary art. How this happened, and why this world proved so compelling for him – the co-founder of Europe’s leading resale marketplace Vinted, who continues to make successful investments in tech projects around the world – is what we talked about with Justas.

Southbank Centre’s Hayward Gallery. Photo: Southbank Centre

Justas also told me about another critically important figure behind Upė: London-based Lithuanian curator Adomas Narkevičius, who has also been appointed co-curator of the Latvian Pavilion at next year’s Venice Biennale. The pavilion will present Untamed Assembly: Backstage of Utopia, a project by Bruno Birmanis and MAREUNROL’S, an exhibition dedicated to the radical legacy of the Untamed Fashion Assembly. Within Upė, Adomas has taken on the role of founding director, following curatorial roles at Cell Project Space in London and the Rupert Centre for Art, Residencies and Education in Vilnius.

During our conversation, Justas spoke calmly, outlining his vision of Upė’s mission step by step, idea by idea, and emphasising the importance of supporting the Baltic art scene, which he sees as standing on the threshold of a significant transformation. What kind of transformation? Let’s give the floor to him.

Justas Janauskas and Adomas Narkevičius. Photo: Anne Tetzlaff

How did your interest in contemporary art become such an important part of your life?

I think it’s important to look at my background and where I come from. When I was ten, I discovered computers and started spending almost all my time programming and learning to code. By the time I was fourteen, I had sold my software, a payroll calculation application, to a local company; they then employed me to develop it further while I was still at school. I was extremely busy. At university I was studying and working at the same time. At twenty-four, while having a full-time job and doing PhD studies (which I quit later), I co‑founded Vinted. Once again, I was completely immersed in work for the next nine years.

In 2017, I stepped back from Vinted’s operations and suddenly became, in a good way, jobless. Overnight, I had all the time in the world again. It was a huge shock. For the first time in my life, I was able to ask myself really fundamental questions: why am I here, what am I doing, what is the purpose of my life, and why do I do the things I do? My identity had been entirely tied to being a Vinted co‑founder and CEO, and suddenly that was gone. I had to rebuild myself.

I tried engaging with many different things, including art. At first, it was quite simple and even banal: visiting art fairs, exhibitions and galleries. This came largely through my wife, who is an artist and has always been involved in the art world. Gabija introduced me to contemporary art, and I started going from one event to another. I didn’t understand many things, but the experience was very positive. Over time, I noticed that I was engaging more and more, and that art was becoming a meaningful part of my life. It became a way for me to engage with those deeper questions about meaning. I began meeting people from the art world – people I had never encountered before. My entire social circle had previously been almost exclusively from tech. I didn’t have artist friends; they simply didn’t exist in my world.

Gabija Grušaitė. Ferma. Installation view. Photo: Jonas Balsevicius

Are people in the art scene very different from those in the tech world?

Very-very different. As I started making new friends in the art world, I found it a really good experience. Gradually, I also began supporting some art projects – for example, Sun & Sea (Marina) (2019) by Lina Lapelytė, Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė and Vaiva Grainytė, presented at the Lithuanian Pavilion of the 58th Venice Biennale or Robertas Narkus at the Venice Biennale 2022. I supported exhibitions, residencies, books, films and music projects, but in a rather sporadic way. Looking back, I think that was the right way to begin. I felt that these people were doing something meaningful, and I was in a position to support them a little – so why not?

At the same time, I began collecting art, very slowly and almost without noticing. I bought one small piece, then another, then a third… And suddenly I realised that it’s a collection. In the last years, however, the number of requests for support increased so much that I began to feel overwhelmed. I understood that if you want to make a real impact, you need to concentrate yourself, you need focus. You can scatter light everywhere, or you can concentrate it into a laser and then with a laser you can cut things. I am a big believer in laser focus, which also comes from my previous career in tech. It’s one of the most important drivers of success when you truly focus on the right things. The difficult part in tech is not just focusing, but choosing what to focus on. If you choose correctly and focus, you achieve results. The same question then came to me: “What should my focus be? Why am I collecting? Why am I doing what I’m doing?”

That led me to the idea of an art foundation with a clear mission as a structure to achieve the focus. But then more questions followed: what kind of foundation, what mission should it support, what projects should it be involved in, and, most importantly, why? How is that relevant to me personally, and how should a bigger group of people benefit from it? I looked at different models and realised that I didn’t want to start another object‑focused foundation, one which collects objects or builds buildings. While they are all necessary, important and very needed, I still think there are already too many objects in the world. In a way, I was transferring parts of the Vinted model into the foundation. Vinted was always about recycling what already exists and providing a platform to connect people in ways which were not possible before. Could we circulate differently what we already have in the art field, and create new connections and experiences that were not possible before?

Geography was another question. Should it be focused on my own country? Or something broader? Eventually, I realised it had to be about connection again – something larger than a single country, but still authentic. The Baltic region felt right, especially when combined with efforts to build bridges with major global art centres.

This resonates deeply with my own life. I come from the Baltics, I live in Italy, I spend a lot of time in London, and I travel constantly. It’s also very similar to the story of Vinted: a company rooted in the Baltics but operating globally. I felt that the similar approach, probably, could work in contemporary art.

Last autumn, I met Adomas Narkevičius, my partner at the foundation, in Paris. That meeting was crucial. I knew I couldn’t do this alone; I needed someone deeply connected to the art world. Our visions aligned perfectly, it was a perfect match, and by December we had articulated the mission clearly: to create new cultural exchanges between the Baltic region and major as well as newly emerging global art centres. We decided to start small, following the idea of a ‘minimum viable product’, MVP, coming from the tech world. We chose London as a starting point, since both of us have strong connections there.

And we focused on curators at the beginning of their careers, because artists from the Baltic states already have relatively more opportunities for residencies and exhibitions. Curators, by contrast, have far fewer. We saw this as a real opportunity to make an impact. The open call launches today, on 10 December, which is very exciting. That’s how my journey into contemporary art led to the Upė Foundation.

Camden Art Centre. Photo: courtesy of Camden Art Centre

Which art institutions from the Baltics and London are involved?

One curator from the Baltics will work at the Hayward Gallery, and one curator from the UK will work at Tallinn Art Hall. Reciprocity is very important to us; this has to be a two‑way street. This first round involves one exchange, and in the spring we will launch a second round with two more participants in partnership with Camden Art Centre. We want to learn from this experience and then decide on the most effective next steps.

The architectural competition for the main building of the Estonian Art Hall was won in 2022 by KUU Architects and Pink. Image: Kuu Architects and Pink

Why exactly Tallinn Art Hall from all the Baltic art institutions?

We spoke with several institutions across the Baltic states, and in this case there was a real sense of serendipity. Tallinn Art Hall is finishing the renovation of its building and opening a new multifunctional space, suitable for exhibitions, music and other activities. They were looking for young, dynamic divers who could run that space and curate the programme. So that was the first thing they really needed – something like what we were offering. In return, they were able to provide a very cool space and a very appealing position for that person. That was an obvious perfect match again.

What’s important about these fellowships is that they are long‑term – up to eighteen months, not just a couple of weeks or months. We want people to build real, lasting relationships. A curator from the Baltics will spend eighteen months in the UK, deeply engaging with the local scene, and vice versa. These connections won’t disappear when the fellowship ends; we expect new projects to emerge from them. It’s also important that this experience counts as real professional work. Eighteen months is long enough to be a significant entry on a CV, and participants will be paid proper market salaries.

Beyond this, we are working on other initiatives. One is bringing a Baltic artist to a major UK institution for the solo exhibition – something that would not happen without our support. I can’t name the institution or the artist yet, but it will be a significant moment.

We’re also organising a joint Baltic party at the opening of the Venice Biennale on 6 May. It will be a nice palazzo, great location, a bit of an elegant, but not over‑polished event – something that keeps the Baltic spirit, that wild energy, while elevating the experience.

What do you think Baltic artists and curators can bring to the global art scene?

The Baltic region went through a very specific historical transition – from the Soviet period through the post‑Soviet era, including the turbulent 1990s. This has created a unique artistic sensibility, marked by experimentation, energy and a certain wildness. That hunger and willingness to take risks is something I think is highly valued in places like the UK.

At the same time, UK institutions are very strong in terms of methodology and organisational culture, and there is a lot the Baltic institutions can learn from that. It’s a mutual exchange.

When you say ‘wildness’, what exactly do you mean?

I mean an energy – a willingness to push boundaries, to experiment, and not to be constrained by conventions.

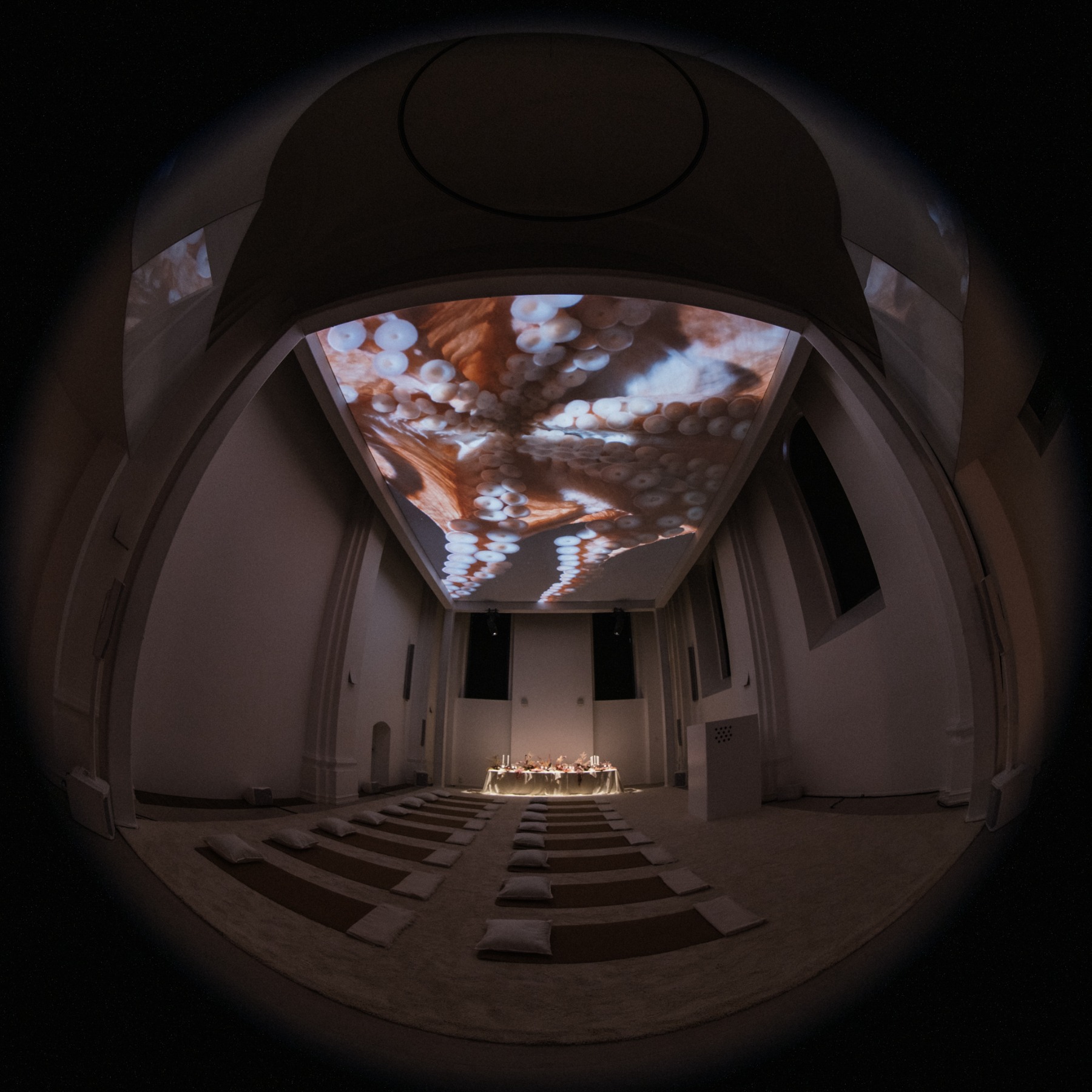

Gabija Grušaitė. Date with an Octopus. Installation view

What qualities do you personally value in art?

I’m particularly drawn to research‑based practices and works that are multi-layered, and ask important life questions. You encounter them once and think, ‘Okay.’ Then after some time you see those or other artworks from the same artists and you learn more about the context, your understanding grows. And then you have an encounter after some time again with that artist or their work and you understand again a little bit more. And it’s like layer upon layer – a kind of never-ending journey. It’s an ongoing process, almost like building a relationship with a person. I find that very meaningful.

Research‑based artists ask powerful questions and build their work around them. Often these are questions you would never have thought to ask yourself.

What are the future plans and missions of the Upė Foundation?

I believe that Baltic art is on the verge of something very important. Artists from the region are increasingly visible at major biennales and international exhibitions. In the near future, the Baltics could become a small but distinct and influential player on the global art stage, comparable to countries like Iceland, South Korea or Taiwan. We're not there, but we're definitely moving into that direction. And one of the missions behind Upė is to facilitate and accelerate this process.

Another is to support the writing of history. The story of contemporary art in the Baltic states has not yet been fully articulated or documented, and we want to support scholars and researchers in doing that. This is also a crucial part of building the future of the region’s art scene.