Curating a poem

An interview with the new director of CAC Vilnius, Valentinas Klimašauskas

Valentinas Klimašauskas is a curator and writer well known throughout the Baltic states. His attentive, caring, and poetic vision, as well as his ability to craft ideas and construct communication, have long made him one of the most recognised and sought-after curators on the region’s art scenes. Just a few days ago, he gave a short lecture at the National Gallery in Prague, where he was introduced as an art practitioner who “innovatively interweaves curating and writing – curating texts and ‘writing’ exhibition projects. His work explores how texts create and reshape institutional frameworks, how curators can work with meaning across different media, and what kinds of reading strategies contemporary art requires today.”

Trevor Paglen, “Behold These Glorious Times!”, 2017. Single-channel video, colour, stereo sound (10 min). Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery, New York. “Bells and Cannons”, Contemporary Art Centre, 2025. Photographer: Andrej Vasilenko

In his 2017 interview with Arterritory, when he was invited to work as programme director of the Riga art centre Kim?, Valentinas recalled: “I remember being six and asking my mom to let me make my own display of various aromatic soaps that she collected. I recall spending hours arranging different packages on shelves, realising how many possibilities I had. Since then, that feeling of recognising your own limits, as well as the endlessness of the inside and outside worlds, has been both intoxicating and sickening.” Over time, also the scale of this “display” has grown considerably – now stretching across a few thousand square metres. Since 2025 he has been leading CAC Vilnius as its director, an institution of great importance not only for Lithuania but for the entire Baltic region. Established in 1992 by the Lithuanian Ministry of Culture, the CAC later replaced the Arts Exhibition Palace and took over its building on Vokiečių Street 2 in Vilnius. The main venue of the CAC reopened in mid-2024 following a major renovation that began in 2021. In spring 2024, the CAC also expanded its activities by opening a new branch in the Antakalnis district of Vilnius – the Sapieha Palace – where contemporary art is exhibited in dialogue with the historic building and its architectural ambience.

How does the new director of CAC Vilnius see the present and the future of the institution? How can the practices of writing and curating intersect and enrich one another? What challenges does our time pose, and how do artists respond to them? These were the questions we discussed with Valentinas on the very days he was flying to Prague and returning to Vilnius, uncertain whether his flight would even land at his home airport, which had been temporarily closed several times due to balloons carrying contraband crossing the Lithuanian border from Belarus.

Tobias Zielony, “How to Make a Fire Without Smoke”, 2025. HD video, colour, sound (21 min 9 sec). Courtesy the artist. In the background - Henrike Naumann, “Breathe”, 2023. Coat rack, two stools, textiles, ceramics, ears of corn, chain gloves and shirt, monitor and video, dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist. “Bells and Cannons”, Contemporary Art Centre, 2025. Photographer: Andrej Vasilenko

I assume that CAC Vilnius has long become an important part of your life. What are your first memories associated with this place and this institution?

I have a few old and odd memories – but I'm not sure about their chronology.

I remember hitchhiking from Kaunas, where I studied, to visit CAC exhibitions around the turn of the millennium. The exhibitions by young artists mesmerised me. In one, I saw a radiating beauty in blue, sleeping. Nearby, there was a sculptural prism emitting the smell of coins that people had thrown into some fountain in Palanga – for luck. In another exhibition, you could see the performance of a naked woman inside a huge amniotic sac filled with honey. In yet another, there was a young artist’s retrospective that deconstructed the oeuvre of Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis – who at the time was considered the only Lithuanian artistic genius.

At the CAC café, some other emerging hyperactive artist took a potato pancake from my plate with his smoky hand and looked provocatively into my eyes while eating it – and drank my beer.

Maybe not in that order, and some memories of exhibitions by Donatas Jankauskas – Duonis, Eglė Rakauskaitė, and Darius Žiūra – just to name a few – are not exact, but it was at the CAC that I first realised that visual arts could represent reality and imagination in complex, poetic, punk, contradictory, brutal – and at the same time – beautiful ways.

You worked at CAC as a curator for 10 years (2003–2010). What was your most challenging experience during this time? What did you learn then about the nature of curating?

The scene is constantly changing thus every time you think you have learned something new about art most probably already is old news. This is also how Pierre Bourdieu is defining the cultural field in general – the cultural field is in permanent rivalry for symbolic capital. However, I believe the beauty of more successful curatorial projects lay in curating the moments that unite us, many of us.

The most challenging experience is being underpaid – the cultural workers were drastically underpaid then as they are now. I’m still thinking how this insecurity changes us in unexpected ways – how we became more risking, mad, burnt out, productive, competitive, but also emphatic, sensitive, funny, etc. However, as the scene is constantly changing it feeds in fresh blood and talent and it seems that there is abundance of it in Vilnius and beyond.

“Bells and Cannons”, exhibition view. Contemporary Art Centre, 2025. Curators: Virginija Januškevičiūtė and Valentinas Klimašauskas, architect: Gabrielė Černiavskaja. Photographer: Andrej Vasilenko

You also have a writing background – or rather, writing is a very important practice for you as well. You’ve published several books: Polygon (Six Chairs Books, 2018), B (Torpedo Press, 2014), and Alphavilnius (Kitos knygos, 2008). Are these works prose or poetry? And how does your experience as a writer influence your curatorial work? Do you form exhibitions as a kind of reading process for the viewer?

My last book is titled “Telebodies. Bleeding Subtitles for Postrobotic Scenes” (Mousse Publishing, 2024). It was promoted as a strange hybrid of Teletubbies and Videodrome in the age of algorithms. It also functioned as a practice–based fine–arts doctoral thesis at the Vilnius Academy of Arts.

The other is Polygon (Six Chairs Books, 2018). I forgot its plot now, but according to its translator Erika Lastovskytė, it “follows a foreign investigator, a character of thousand faces and identities, who arrives in Vilnius on April Fool’s Day with just twenty–four hours to decode a cryptic password: a violet city gate. What follows is a kaleidoscopic journey through the city’s landmarks accompanied by a local poet and a retired interrogator –encountering plane spotters and Vilnius mademoiselles; discussing art, philosophy and literature; exploring CIA Black Sites, memory palaces and urban portals.”

My first English book was “B and/or an Exhibition Guide in Search of its Exhibition” (Torpedo Press, 2014). In it I was using imaginary or language-based artworks and artefacts by various, including, fictional artists to stage situations for written exhibitions that might be set or located in someone’s head, Palaeolithic Chauvet cave, a collage of footnotes, floating in memory or the outer Solar system with Voyager 1, to mention a few.

At that time I was curating texts and writing shows. While being interested in speculative economies of language, I was trying to link concepts & readers into language-based performative systems. Generally, when I curate I start from a curatorial text, thus text, language come first.

Now, I believe that we are all writers, artists and curators, thus, if you know what you are doing, there is no fundamental difference between writing or curating an exhibition, an institution or a poem, just to give random examples.

Curating a poem… what could it be?

Asking different artists to propose a letter, word, title, sentence, metaphor, algorithm, rhythmics, methodologies of performing it, and so on – this could work as curating a poem, I think.

Fedir Tetianych, “Sketch for the Design Project of Kyiv Planetarium”, 1980s. Cardboard, watercolor, gouache, 61,5 × 84 cm. Courtesy the artist’s family. “Bells and Cannons”, Contemporary Art Centre, 2025. Photographer: Andrej Vasilenko

You worked for several years as the programme director at Kim? starting in 2017, which means you’re well acquainted with the Latvian art scene. Recently, I interviewed curator and art critic Krist Gruijthuijsen, and he said: ‘Compared to the other Baltic countries, Latvia feels quite different – more closed off, in many ways. Of course, there are reasons for this, but it affects how artists view the world. From my perspective, Latvian artists tend to have a more introverted way of looking at things’. Do you think he’s right in some ways?

The most internationally successful and interesting artists in Baltic countries are the ones who studied and/or lived abroad and are critical of local art understanding and structures. Maybe it's about uniting hybrid knowledge that they receive while working in different scenes. Contemporary art is international – if someone is just local in terms of themes and discourse, most probably they are not exactly contemporary artists. In that sense, Latvian artists like Viktor Timofeev or Evita Vasilejeva are definitely not introverts – they are open to various discourses, media, methodologies.

In my understanding, Latvian art scene is more decorative and I see it as a result or influence of longstanding tradition of arts being sponsored, funded by private entities, collectors. In Estonia and Lithuania we have strong public institutions thus the scenes can raise fundamental questions about art. Artists here don't necessarily need to get the grace of some business people, for example, who think about art in terms of commercial value or how it would look in their real estate, which in Latvia most probably is also influenced by the amazing local Art Nouveau.

That’s interesting! Because I get the impression from Art Vilnius that Lithuania has more collectors – especially mid–level ones. Maybe not even collectors in the full sense of the word, but people who are interested in coexisting with art in their own space. And just yesterday, at a public discussion about the artist’s place in society, participants were lamenting the weakness of the art market in Latvia. There are a few big collectors, but the mid–level is almost missing.

Although sometimes they overlap, public and private institutions see value differently. Public institutions are more important for the scene than collectors – they normally invest into the richness of the scene, into its ecology, meaning and its future. While collectors are hunting trophies or connections to the most important, emerging, valued figures, exchanging their monetary capital into symbolic capital. The best for the scene is when public and private goals unite for larger good, like building public museums and collections – in times of permanent crisis it’s much more functional to work together.

Anna Engelhardt, Mark Cinkevich, Terror Element, 2025. Single-channel video (25 min), television, camera, speakers, briefcase, explosive detection spray, laboratory tables, dimensions variable. Courtesy the artists. “Bells and Cannons”, Contemporary Art Centre, 2025. Photographer: Andrej Vasilenko

What role do you think CAC Vilnius plays in the ecosystem of the Lithuanian art scene and culture, and what would you like to change in its mission?

The role of the CAC has been changing since it was established by Kęstutis Kuizinas in 1992. At the time, contemporary art had a function to modernise the scene and post-Soviet society, emancipate it, and bring some sort of (neo)liberalism which was part of the whole package. It also surprised and shocked audiences aesthetically, technologically, and politically. This is not the case anymore. Now, as we already are full members of the EU, NATO and richer world, our audiences travel and experience art and culture regionally or even globally. Our societies deal with other crises and ask again what functions contemporary or other art may have in the times of AI disinformation, social media populism, climate change and wars of optic cable drones, just to mention a few issues.

In this heavily polarised world, and considering our rather insecure region – which is quite possibly at risk of being occupied or divided again, and which is repeatedly attacked by populist, anti‑Western, and undemocratic parties – I would suggest that institutions should be part of the process of counterbalancing this insecurity and disinformation, uniting and consolidating audiences, and sparking hope. I would like the CAC to be a generous space for authentic artistic visions, one that stimulates audiences and creates room for growth for artists, curators, and the whole scene. It’s not going to be easy to achieve it.

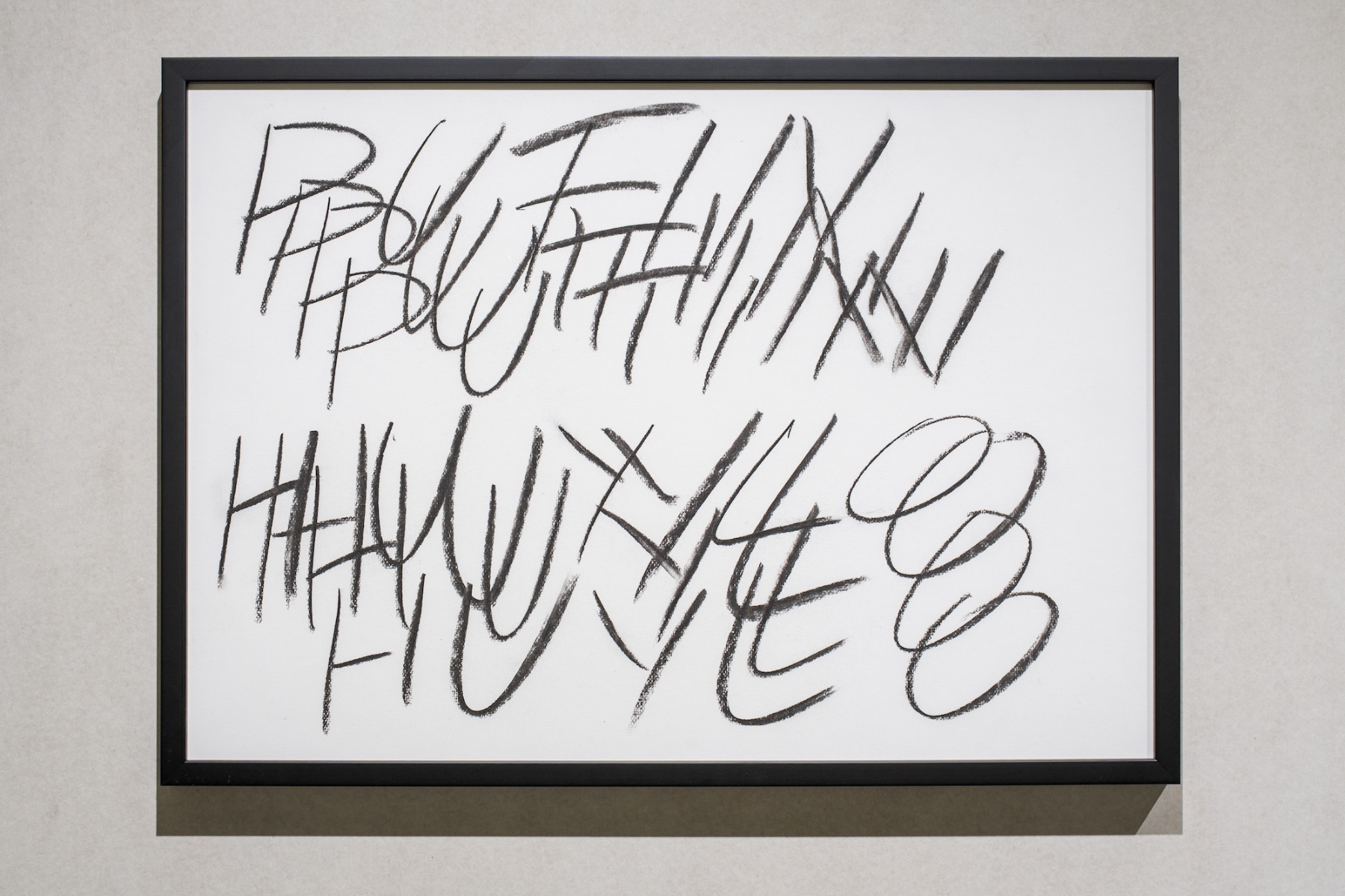

Nikita Kadan, “Putin Huilo No. 1”, 2022. Charcoal on paper, 42 × 60 cm, from the series ‘Repeating Speech’. Courtesy of the artist and Voloshyn Gallery, Kyiv. “Bells and Cannons”, Contemporary Art Centre, 2025. Photographer: Andrej Vasilenko

This year I spoke with the Lithuanian artist and writer Gabija Grušaitė, who presented her work Ferma, which is closely connected to the subject of the frontier. In her video, a narrator’s voice says: “Only as the war of my generation draws closer and the sound of drones enters the nightmares can I finally understand what it means to come from the frontier, a place where social tectonic plates move first… I move as a stork, but frontier is printed in the blood. It is not safe here. But we still grow. Animals, plants, people of the frontier.” As I understand it, this is also a significant theme for CAC. Last year there was the large international exhibition “Borders are Nocturnal Animals,” and this year there is another international group exhibition, “Bells and Cannons”(open until March 1), which “presents different strategies used by contemporary artists in the face of militarisation.” Do these exhibitions intersect with each other in some way?

The exhibitions do intersect and overlap, as they both address political, ecological, and other themes in the context of various wars. Borders are Nocturnal Animals took a more poetic approach and was heavily based on the Kadist collection – the curators Neringa Bumblienė and Émilie Villez created a new and very elegant version of it after it was shown at the Palais de Tokyo during the Lithuanian Season in France.

The shows also have some obvious differences. Bells and Cannons primarily explores the complex relations between art and war through hybrid themes, territories, and (infra)structures. What is considered art one day (bells) could be used as a weapon the next (cannons).

I am writing this answer on a plane in the middle of a balloon crisis in Lithuania and I am not sure whether my plane will get permission to land due to safety concerns. Cigarette smugglers keep sending balloons with cigarettes and SIM cards that emit GPS signals when the wind is favourable; these are later tracked and retrieved in Lithuania. The question is – is this a form of hybrid warfare against Lithuania, or just small‑ to medium‑scale tobacco‑mafia operations? Some politicians claim the former, while others deny it. It certainly sows panic and chaos, and also makes Vilnius and Lithuania appear untrustworthy.

Accordingly, coming back to the exhibition, quite many artworks in the exhibition question both civil and military usage of image making, technologies, infrastructure, and other realms, be it AI, pipe from Siberia to Germany or an art exhibition.

Philipp Goll, Oleksiy Radynski, Hito Steyerl, “Leak”, 2024. Pipeline structure, 5-channel video (21 min), sound. Courtesy the artist, Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York and Esther Schipper, Berlin/Paris/Seoul. “Bells and Cannons”, Contemporary Art Centre, 2025. Photographer: Andrej Vasilenko

But do you see or feel this ‘frontier’ mindset in the Lithuanian or other Baltic art scenes? Or is it not yet fully recognised by artists and reflected in their work?

Sometimes, yes. It is rather rare that artists are genuinely interested in – and successful at – depicting objective and concrete geopolitical realities in their practices; a specific mindset is required for that.

However, good artists generally tend to reveal or challenge frontiers – of time, style, personality, gender, ethnicity, culture, and so on. It should also be noted that art and artists need to challenge their own instrumentalisation, as they can easily become tools of propaganda. Autonomy is important even at the frontiers – perhaps even more so than anywhere else. To quote Jacques Rancière: “The function of art is not to be a direct tool for political propaganda, but to challenge our perceptions and create new possibilities for understanding the world and society.”

‘Borders are Nocturnal Animals / Sienos yra naktiniai gyvūnai’ exhibition view. Contemporary Art Centre (CAC) Vilnius, 2025. Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

‘Borders are Nocturnal Animals / Sienos yra naktiniai gyvūnai’ exhibition view. Contemporary Art Centre (CAC) Vilnius, 2025. Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

What do you find the most interesting and impressive tendencies in the global art scene? Which of these would you like to bring into the Vilnius CAC?

At this moment, I am primarily interested in the region. I believe that what happens now will define who we will become in the future, perhaps for generations to come. I am referring to protests against undemocratic populism, Russian imperialism and the war in Ukraine, and seemingly secret deals between the US and Russia concerning the borders and future of Central and Eastern Europe.

Nevertheless, I would like to begin the new CAC programme with an international group exhibition that responds to the context of intensifying social fragmentation and polarisation. It would be a predominantly figurative art exhibition, exploring various strategies for developing a relationship with the other, with the aim of creating long‑lasting or temporary connections and/or communities. The exhibition would seek to establish new relationships between historical and contemporary, local and international artists of different generations, their practices and scenes, reflecting the richness of personal and collective stories and subjectivities – ecological, postcolonial, intergenerational, hybrid, queer, and so on.

And in the second half of the year we plan solo exhibitions by Lina Lapelytė and Agnieszka Polska, artists who have powerful and extinguished practices and who, in my opinion, are between artists who define what is contemporary art of the current decade in the region.

Credit: "Breaking the Joints", exhibition view, Sapieha Palace, 2025. Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

Are you also responsible for the new CAC art centre at the Sapieha Palace, which is housed in a historic and very impressive building? What kinds of exhibitions are planned to be held there?

Sapieha Palace has its own curatorial team. I’d like to quote its Head of the Art Programme Edgaras Gerasimovičius:

“Although contemporary art plays a central role here, it’s important to note that – unlike at the CAC – it forms a distinct part of the broader programme, alongside initiatives managed by other departments. Alongside the exhibitions, the palace hosts classical and contemporary music concerts, a lively educational programme, and various activities related to both tangible and intangible heritage. Each year, the curators organise two to three short–term solo exhibitions. In 2026, the programme will open with a solo show by Lithuanian artist Tata Frenkel. The programme also includes what is called the major exhibition – a large group show running from April until the end of the year, built around a central theme. Next year’s edition will explore how digital technologies shape intergenerational relationships. Every year, SR also organises a symposium that brings together researchers and artists from different fields. Next year, the focus will be on storytelling and explore a range of directions – from speculative storytelling and feminist listening to questions around the archive, witnessing, and what happens to narrative in our postdigital world. And finally, they also run a Moving Image programme, often accompanied by conversations with the participating artists. That’s what we can share for now, but do keep an eye on SR – they will be announcing the full programme in more detail later this year.”

Do you see AI as just an interesting new tool for artists, or as a new player that will change the rules of the art scene?

Depending on how you define the AI, its concept and imagery has been part of art already for a long time. I’d say that we already live in postrobotic or postalgorithmic times – we already don't notice its influence, it's already an integral part of our lives. Think of how texts are being edited, including this one, think of how still or moving images are being made – by using pattern recognition software and chips that are using AI – and even painters are heavily influenced by AI inspired imagination. So far the rules are the same – AI is still a tool however, it's a tool that not necessarily is being owned and controlled by the artist. And this is why we see a big change – artists are fighting back to get back control of imagination and their artistic instruments, which already might be too late. It's not an accident that quite many young artists returned to a brush and canvas – neoliberal, corporate, ideological, opaque side of AI is not that sexy anymore.

Photo by Tautvydas Stukas

These times are quite sad and exhausting in themselves. Where do you find inspiration for your work, for new projects, for this endless ‘burning’?

I'm not exactly a burner, I'm more of a long distance runner. Maybe in responsibility to friends, family, employees, predecessors? It's just one of the dark pages in the book about permanent human struggle which has many darker pages. We should write it with dignity and inspiration. No one expects from us less.