Unease at its Best

Gallery Weekend Warsaw 2020

Jurriaan Benschop

Considering the corona context, expectations for the 10th edition of Warsaw Gallery Weekend (1/10 – 4/10/2020) were modest. Dinners and events were cut and the program reduced to what it was initially about: having exhibitions throughout Warsaw in (temporary) gallery spaces. And then, a lot of people did actually show up and occasionally even had to queue to keep the amount of visitors safe, says Kasia Sagatowska of Jednostka gallery. She is showing photographs by Weronika Gęsicka that picture American suburbia underneath the neat and smiling surfaces. The artist found her motifs through stock photos by, for example, looking for keywords such as “holiday” or “homes”. Then, while processing the results, she creates distortions or introduces ambivalence into the motif. In odd ways she makes the photos look more realistic – in the sense of adding a healthy portion of absurdity or ugliness to them. Cliffhanger is one out of a few exhibitions in Warsaw that combines formal strength and beauty with a sense of unease. What could fit the current times better than that?

Weronika Gęsicka at Jednostka, Untitled #4 Cocoon

The sculptures of Krystian Truth Czaplicki are as weird as they are well made. In the huge space of Piktogram (formerly used by the School and Pedagogical Publishing House), there are three figures with beards looking down onto the viewers. They are not necessarily men (or not just men), with their smooth plastic bodies and arms consisting of colorful product labels. The artist did not want to give any explanation about the works, or speak about his motifs. He just provided a typed sheet at the entrance of the show, with some dialogue from the film The Matrix Revolutions. A sampling of some of the lines: “Do you believe you're fighting for something? For more than your survival? Can you tell me what it is? Do you even know? Is it freedom or truth? Perhaps peace? Could it be for love?”

Krystian Truth Czaplicki, exhibition "Amateur Threesome" at Piktogram

These questions set the tone and give some hints as to what the sculptures could mean. To me they are fascinating even before the question comes up if I like them or not. The material authority in the work is convincing, which supports their ambivalence in terms of gender and mental state.

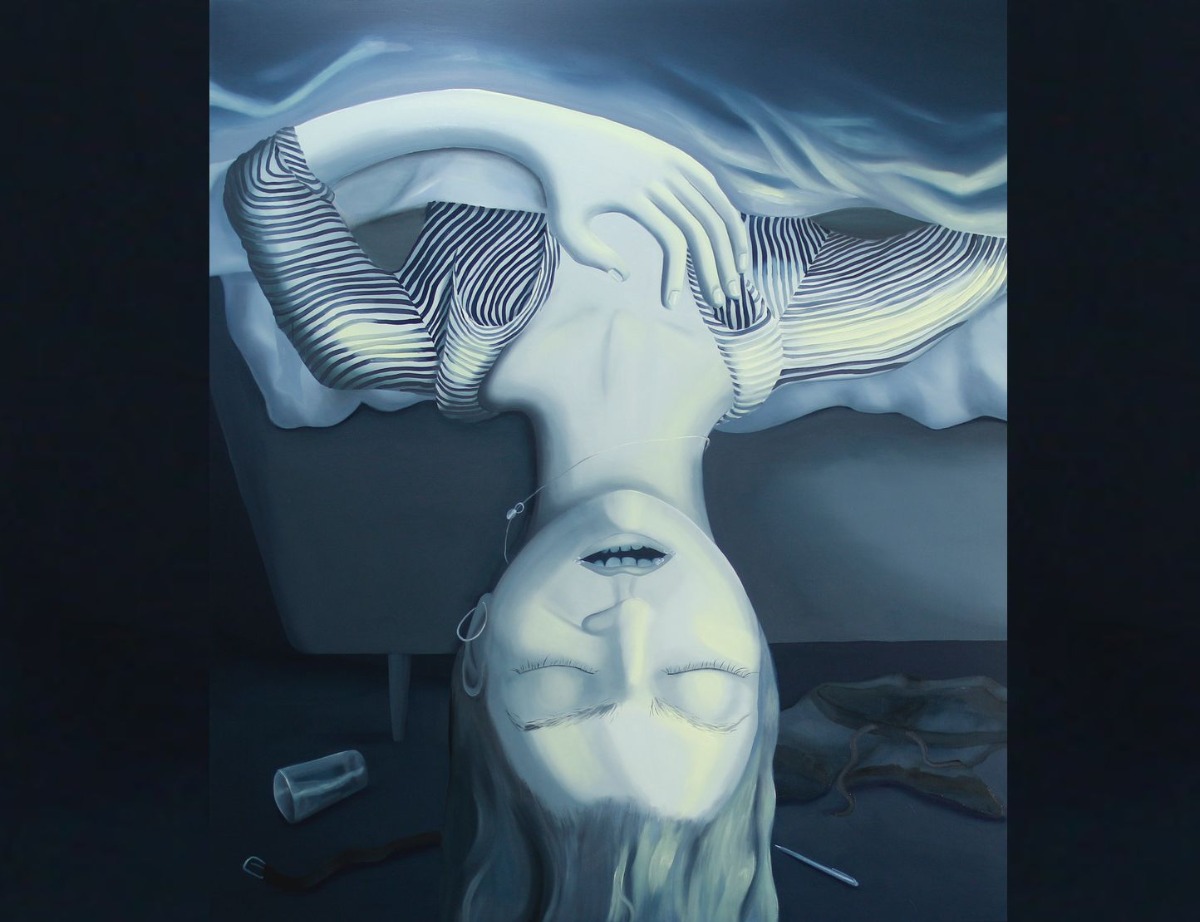

Karolina Jablonska at Raster, self portrait sleeping, 160x135 cm, ooil on canvas, 2020

Throughout the gallery weekend I find some shows that appear urgent, and this seems to be because the artist worked with persistence and precision around “an issue”. Gallery Rodriguez even made “persistence” the thematic focus of a group show presenting contributions in diverse media. It makes one curious to see more works of the individual participants and about the Poznan-based gallery’s program. It is probably not so easy for an artist in these times of spreading Covid and manipulating politicians in Poland and other countries to strike a chord that feels right and that matters. Among the few painters that succeed in that effort is Karolina Jablonska, who is showing a series of recent works at Raster along with the photographic works of Sophie Thun. Jablonska took herself and her domestic situations as her model, and we see a figure having to deal with (maybe too) much self-reflection. “It is not so much about me or showing a self-portrait, but more about the feeling of a generation,” the 29-year-old Krakow-based painter says. She finds herself rather isolated in lockdown times, refraining from traveling and having at home this window to the world called the Internet, which brings all kinds of contradicting information and connections. The paintings show how such a mix may feel. They are special in the reduced and pale light, and balance between a self-ironic appearance and a melancholic one.

Often in galleries you find a leaflet that explains to the viewer what the artist meant and how the works should be understood. As often as not, these texts are far-fetched, trying to prove too hard the significance of the works on view in the context of current times. For this reason I appreciated Czaplicki’s refusal to accommodate us with a direct explanation. Instead he offered a mental detour. He recalled the story about the moment that the American painter Philip Guston showed figurative works for the first time, in 1971, breaking away from abstraction. Quite a number of people were shocked and judgmental about that, as they believed he was breaking away from the “purity of means”, which was considered holy in high modernist times. Yet fellow painter Willem de Kooning came up to embrace him and congratulated him. He said: “You know, Philip, what your real subject is? It’s freedom!”

Agata Bogacka at Pola Magnetyczne exhibition "Demonstration of Pictures" / WGW2020. Photo: Bartosz Gorka

At Pola Magnetyzcne gallery, Agata Bogacka is presenting a series of paintings titled Demonstration of Pictures that show color formations on raw canvas. The color planes intersect and overlap each other, creating friction between depth and proximity. Some of the paintings have a landscape feeling, even though nothing is confirmed in the sense of depiction. The paintings appear pretty sparse, yet well considered, charged, and sometimes gloomy. The artist stresses that she wants to leave out concrete defined meaning. Yet she also wants to point to the fact that current developments in Poland (say: life) are all part of the mix, and pouring into her paintings. She enforces this with some video material that shows footage of demonstrations. In front a painting called Equality Dream, the artist and one of the gallery owners elaborated on the precarious situation for the LGBT movement in Poland, which is ‘deconstructed and subsequently reconstructed’ in this painting. Here the story rather kills the work and turns it into a political illustration. This seems unnecessary as the paintings themselves don’t need much words to hold up. In fact, their quality recedes in a kind of reluctance to be explicit about things. The titles of the paintings, such as Negotiations and Divided View, seem more appropriate as they remain abstract like the works themselves.

Monika Sosnowska at Zacheta, Warsaw

The good thing about a gallery weekend is that between the exhibitions you absorb views and impressions of the city, which adds meaning and gives context to the experience of the art. In Warsaw, especially in the center, which is where a lot of the galleries are located, the architecture is both impressive and oppressive; the city seems like a jungle in terms of styles, and Babylonic in its vertical ambitions. Even as a tall man, I feel small between the corporate buildings and the highways crossing the city, speeding up the pace of life. Warsaw is a city where you can’t escape to think about what it means to be modern and how this notion changed through different stages of governing – from state-planned to the current freestyle capitalism. In the present city political arena, there really isn’t any planning going on concerning buildings and construction, says Monika Sosonowska, who is holding her first institutional show in Poland at the Zacheta Museum. In her early works, Sosnowska looked into the different faces of modernism through following the demolition of architecture in her own city. In later work she broadened the question and focused on the roots of modernism, including in other countries such as Russia, and more recently, Bangladesh. The show at Zacheta gives an impression of the scope of her interest, which starts with observing architectural elements, and then translates this into sculptural thinking. Some of her works were made by creating material fatigue on purpose, stretching or bending steel until it cannot take any more pressure.

Joanna Piotrowska at Zacheta, Warsaw

Another show in Zacheta that draws one’s attention is by Polish artist Joanna Piotrowska. Her work in photography and film shows the human body in uncomfortable and awkward poses, or performing repeated gestures and building up tension through that. Piotrowska’s and Soswowka’s shows are unrelated but have been presented on the same floor, and there appears to be an interesting symmetry between them. While Sosnowksa’s sculptures can make us look at steel objects as if they have human characteristics, Piotrowska seems to offer us insight into the architecture of the body. Through a grammar of gestures, we learn how body language is connected to intimacy, power, and manipulation. Both oeuvres are the result of a persistent focus on certain visual languages and experimenting with that. The urgency of these works springs from their friction and discontent in combination with precision in their technical execution.