News from Poland

The 11th edition of Warsaw Gallery Weekend and other Polish art world news

Warsaw was lovely on the first weekend of October: the morning sun chased away swathes of fog between high-rises surrounding the iconic silhouette of the Palace of Culture. After a breakfast and coffee, groups of Varsovians and visitors of the city took to the streets, armed with little red booklets featuring a map of venues hosting the Warsaw Gallery Weekend (WGW) ‒ an umbrella event covering new exhibitions at 31 art galleries. The project has been taking place in the Polish capital for 11 years running; not even the pandemic has managed to thwart it: the 10th ‒ anniversary ‒ edition was successfully held in September 2020. The idea behind the project is concentrating the artistic resources, drawing the attention of collectors and the general public to Polish artists and international guests of the local art galleries. And yet it would not be correct to say that every single gallery operating in the city had been squeezed into the programme of the WGW project: not at all; a clear-eyed aesthetic-driven process of selection had taken place, leaving outside a considerable number of galleries dealing in purely commercial art. In 2019, the rejected galleries made a point of holding their own alternative ‘gallery parade’ that coincided with WGW; however, judging by the fact that no similar event took place in 2021, the plan must have not been worth the trouble.

Włodzimierz Jan Zakrzewski.

Warwick. 1996. From Olszewski Gallery exposition

WGW, on the other hand, is a traditionally successful event. In a conversation at the WGW closing afterparty, Katarzyna Piskorz, the artistic director of the HOS Gallery that had by the time sold almost everything on view at the current solo exhibition by the young Polish artist Konrad Żukowski (with the exception of a couple of conceptual objects), lamented the fact that interest from art collectors ‒ impressively strong during these October days ‒ sadly was, she said, nothing like that during the rest of the year. The three days of WGW are filled with hype and excitement that feeds the Polish contemporary art scene, which, under the current circumstances, is directly dependent first and foremost on the level of activity of private galleries and art collectors.

Fragment of the exposition by Jadwiga Sawicka at the gallery BWA Warszawa. Photo: Sergej Timofejev

Because, after all, during these years of right-wing political dominance in Poland, institutional support has been reduced to nearly non-existent. The art institutions themselves have been under relentless pressure from the powers-that-be and subject to constant attempts to replace art professionals holding leading posts with placemen. Which is exactly what happened not so long ago at Zamek Ujazdowski, one of the largest state-owned art centres in Warsaw, where the new director was unceremoniously appointed without any competition last year. This year, under his patronage an exhibition called Political Art was unveiled in late August to loud protests from antifascist and LGBT communities as well as Warsaw’s Jewish organisations. An international show, the exhibition brought together a motley crew under its wing, from artists protesting against violation of human rights in Iran or Hong Kong to the ultra-right, the likes of Dan Park, who was arrested in his native Sweden for staging an art action that saw him place swastikas and boxes with Zyklon B signs (the brand name of gas used in mass murders of Jewish people during the Holocaust) in front of a Jewish community centre in Malmö. This ‘one size fits all’ approach presents the ultra-right as the same kind of victims as, say, the Hong Kong students or Iranian feminists ‒ a manipulative gesture that is frequently employed in populist practice. And yet the momentum of everything achieved under the tenure of the previous directors of the centre still make it possible to open exhibitions like Everyday Forms of Resistance – the result of several years of collaboration between Polish and Palestinian artists, an amazingly human and communication-driven statement on the extremely complicated situation in the Middle East. Significantly, a plaque at the entrance to the show informs that the participating artists do not wish to have anything to do with the ‘directorial’ exhibition taking place at the same time and in the same building.

Zuzanna Hertzberg. ש (Szin). 2021. At Biuro Wystaw

Małgorzata Mirga-Tas. Out of Egypt. 2021. At Biuro Wystaw

It was while we were wandering around the ‘Palestinian exhibition’ with Dorian Batycka, an art critic from Canada, and curator Inga Lāce when the news reached us that the Polish pavilion at the next Venice Biennale will be curated by Joanna Warsza (co-curator of the ongoing Survival Kit 12 in Riga). As before, the Polish participation at the Venice Biennale is commissioned by a panel that is still not dominated by right-wingers ‒ but then again, it is anyone’s guess where we will be at in two years. Joanna with co-curator of the project Wojciech Szymański will present Małgorzata Mirga-Tas’ show Re-Enchanting the World (since RIBOCA2, our audience is quite familiar with the term ‘re-enchantment’). The project ‘is proposing a new narrative about the constant migration of images and mutual influences between Roma, Polish and European cultures’. One of Małgorzata’s signature works, Out of Egypt, was shown as part of the WGW programme at the exhibition that ran at Biuro Wystaw art space (operated by Polish Modern Art Foundation). It is a colourful patchwork piece, one of a series of stylistically similar works re-interpreting early 17th-century etchings dedicated to stories from the life of Roma people ‒ recreating the scenes with the help of objects and fabrics used or worn by members of her community. The actual exhibition at Biuro, entitled Asymmetry, features works by artists who interpret the subject of identity in the widest possible sense ‒ rooted in the current situation and the existing traditions of Romani, Belarusian, Jewish and Ukrainian cultures.

Alla Savoshevich. Pose. Position. Way. 2019. Photo: Sergej Timofejev

Incidentally, another work from the exhibition ‒ Pose. Position. Way – was the recipient of the prestigious WGW special prize traditionally awarded by the ING Foundation (the award ceremony was held at the citadel of contemporary Polish art, the Zachęta National Art Gallery). It was an object and a video by the young Belarussian artist Ala Savashevich (1989), whose work is always rich in content and metaphors: a pair of high-heel shoes where the heels are actually Soviet stars, piercing the feet in white stockings on every step with their sharp top points. In her interview for the salive.live project she describes her work in the following way: ‘I was thinking about a collection of impractical shoes, the type that doesn’t really suit us or feel comfortable, but we still have to wear. (…) As an artist, I want to draw attention to the issue of objectification in general, and that of women in particular. And the symbolic Soviet star, biting into the heel of a leg dressed in a snow-white stocking, is about what is left of the past and is still with me.’

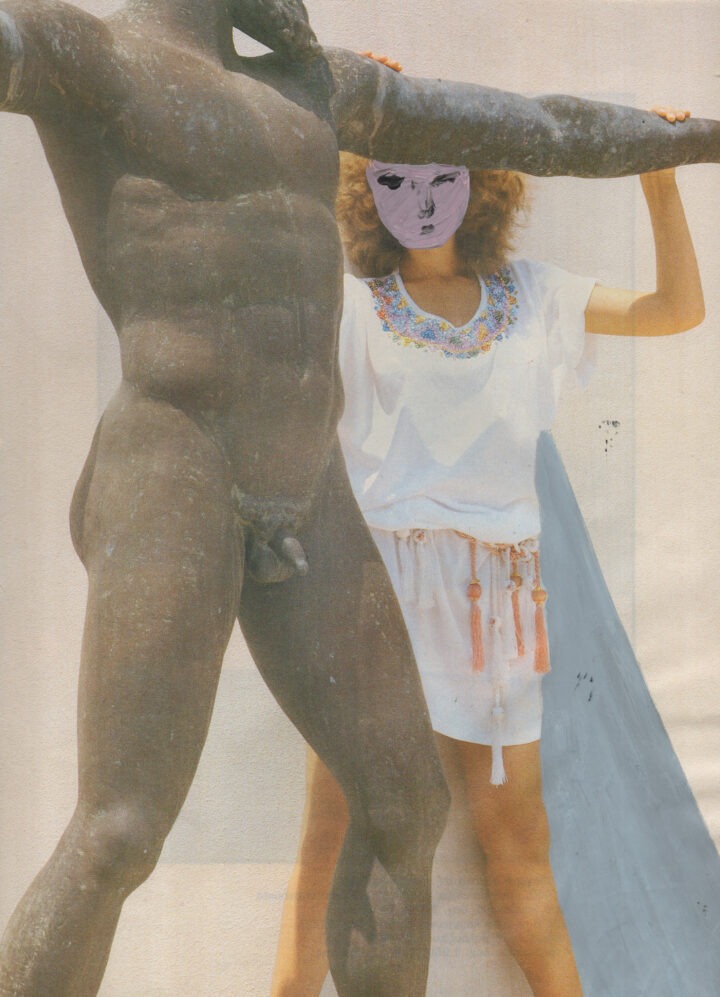

Irini Karayannopoulou.

Woman with statute #2. 2021. From the exhibition organized by the Polana Institute

A couple of international projects were also presented by art institutions like Polana Institute (an exhibition by a group of female artists, She ‒ Classicità) and Instytut Fotografii Fort (a show dedicated to cross-dressing and similarly themed home movies entitled You’re Gone Incognita), while Monopol Gallery showed photographic experiments by an artist from ‘a country that no longer exists’, the former resident of GDR Gabriele Stötzer, and Galeria Dawid Radziszewski ‒ paintings by the Japanese artist Yu Nishimura. Sadly, no projects from the Baltic countries. The rest of the galleries mostly showed Polish artists of different generations and different weight categories on the art market. At the same time, some of the exhibitions could actually be considered as trips to places outside the Republic of Poland, involving deep immersion into the local realities. Among them was the Dust exhibition by Karolina Breguła, who had productively spent the time of her residency in Taiwan, creating a number of videos, objects and even a book about the Taiwanese who refuse to leave their houses that are scheduled for demolition. It was a very well-thought-out and warm exhibition where every detail works to create a narrative and take you to the life and circumstances of people who actually are so far from you. Even the TV sets with the videos were mounted on special consoles reminiscent of bars on ground-floor windows and the structure of this type of houses in general. The show was housed in the local_30 gallery, traditionally working with multi-media projects while mostly representing female artists.

Karolina Breguła, at the Dust exhibition. Photo: Sergej Timofejev

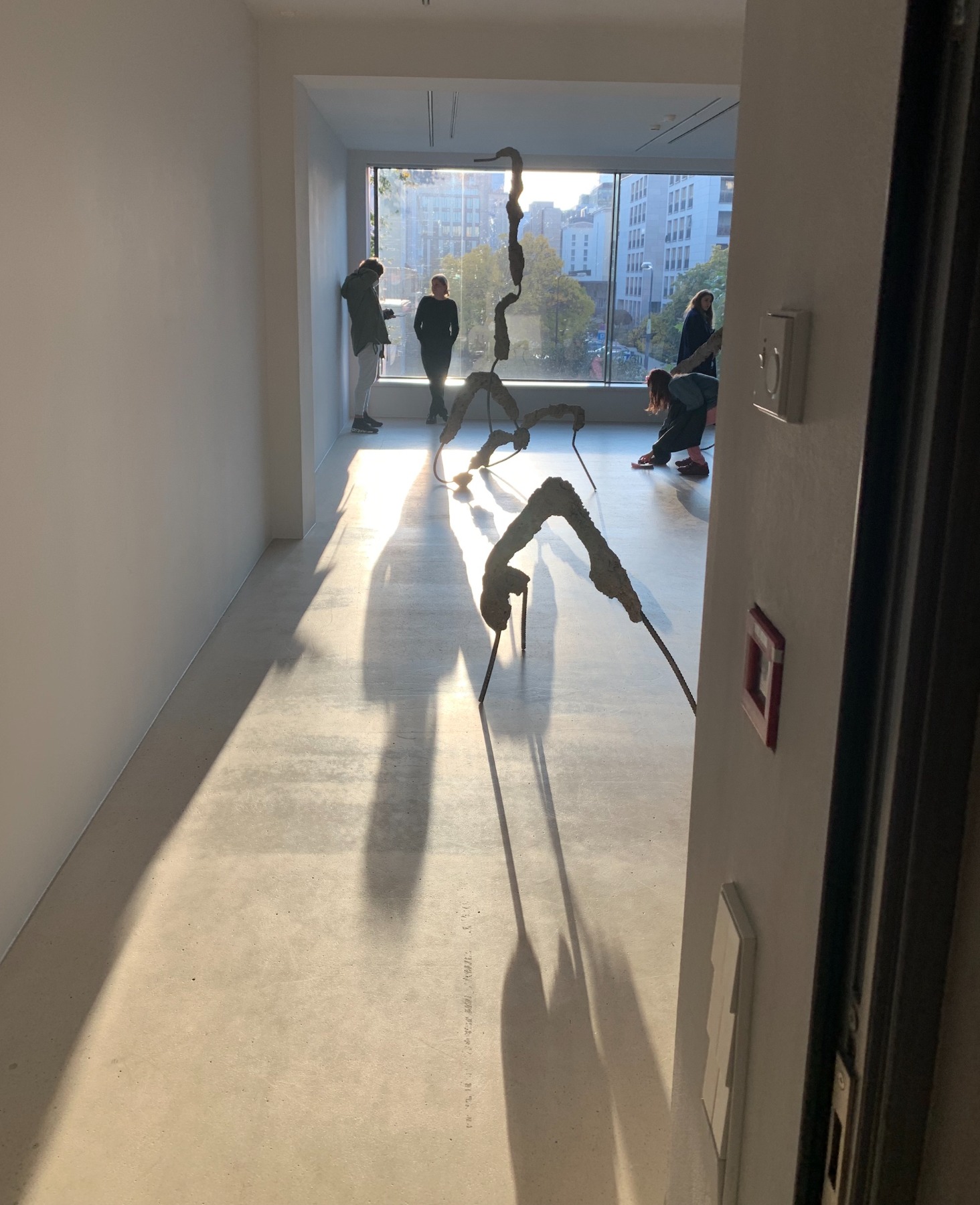

Works by Monika Sosnowska / Fundacija Galerii Foksal. Photo: Sergej Timofejev

But what did two old-timers of the Warsaw gallery scene, Fundacija Galerii Foksal and Raster, show? At the former, Monika Sosnowska had set up something like a zoo of weird twisted creatures made of concrete on top of iron reinforcement rods (interest in architecture and its materials is quite traditional for Sosnowska) and Piotr Janas showed his paintings ‒ half-figures, half-shapes, some kind of bits and pieces suspended in the white milk of the background.

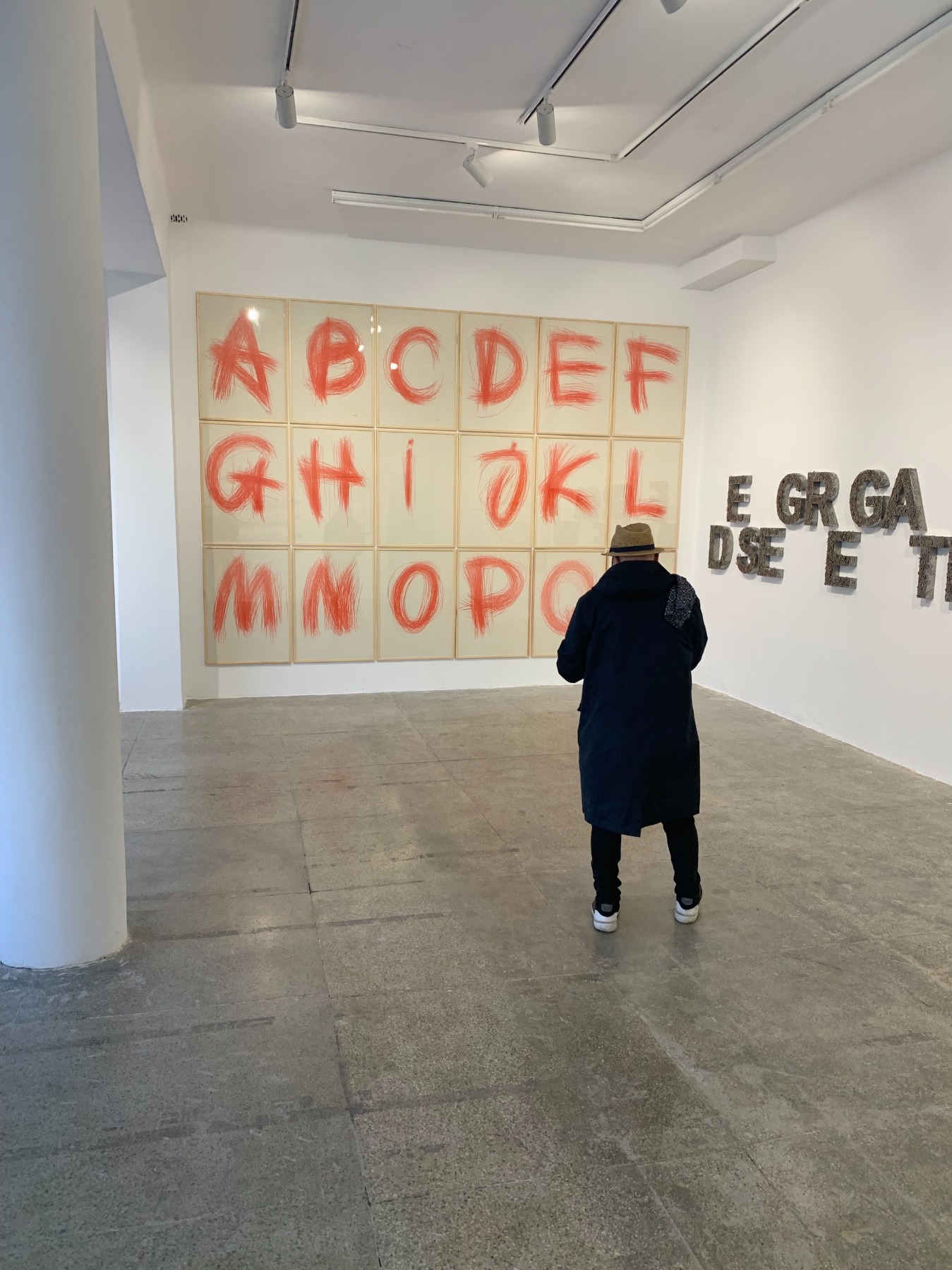

Exhibition of works by Marcin Maciejowski at the gallery Raster. Photo: Sergej Timofejev

Raster, on the other hand, remained faithful to the familiar social- critical context and presented an exhibition of works by Marcin Maciejowski, an excellent painter who ironically and convincingly captures reality of various kinds, be it curator Ewa Tatar’s Instagram page or a scene of a formal meeting of Polish culture officials. Moreover, the painting is often supplemented with text, a kind of commentary on the image that nevertheless also adds a sense of critical detachment to the picture (a shout-out to the comic culture and the oeuvre of Roy Lichtenstein).

Works by Tomasz Kulka at the gallery Propaganda. Photo: Sergej Timofejev

Another art gallery with a long and successful history ‒ Propaganda, one of the original organisers of the first WGW editions ‒ has left its familiar space and given up permanent exhibitions in favour of site-specific projects realised in various locations. This time around, they had chosen the Warsaw Museum of Pharmacy (founded and named in honour of Antonina Leśniewska, the first female pharmacist in Warsaw) to present Tomasz Kulka’s show Fruit from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, where the artist used the plants he had gathered to create his own homunculi under glass covers ‒ exhibited back-to-back with a series of traditional egg tempera paintings on gilded boards, multi-figurative scenes somewhat reminiscent of altar pictures by Bosch except here paradise (or the paradise garden) is spared the proximity of hell. People simply wither lie flowers and fall to the ground like petals or buds, becoming an illustration to the eternal circle of nature. The curator of the gallery (and active contributor to the organisational process of WGW) Jacek Sosnowski believes that Tomasz Kulka’s goal was creating works that transmit a certain aura while not signifying anything specific despite their obvious formal symbolism. And yet they clearly work, he says ‒ guiding the viewer toward reflections on the subject of the actual medium of painting.

Jakub Gliński in front of his work at the 'You Are Too Close' exhibition / Gunia Nowik Gallery. Photo: Sergej Timofejev

Fragment of Yakub Gliński’s You Are Too Close exhibition

The Gunia Nowik Gallery, opened this summer in Warsaw (we published an interview with the owner about the experience of creating a new project in the pandemic times), presented the works of the young yet quickly emerging Jakub Gliński, the new Varsovian Basquiat. Like Jean-Michel, Jakub is largely inspired by street art, graffiti, and images of pop culture, from emoticons to tattoos, arranging his vast aerograph canvases like incredibly subtly fine-tuned streams of consciousness where every element seems completely random at first glance but is actually irreplaceable within the resulting structure of the painting. Jakub painted some of the works in situ, right there at the gallery ‒ wiping off and layering, taking off and adding until he finally felt happy with the result. A grey-blue colour scheme, an intuitive and expressive approach: these are the key features of Gliński’s You Are Too Close exhibition. During the three days of WGW, all of the paintings from the show found their future owners among collectors and art institutions; however, they are still on view at the gallery through 20 November 2021.

Performance ''Fressen' presented by Katarzyna Kozyra. Photo: Sergej Timofejev

Gunia Nowik Gallery was also one of the organizers of the key performative project of the exhibition. Katarzyna Kozyra, who has gone down in the history of contemporary Polish art back in 1993 with her controversial Pyramid of Animals (a work that raised the question of the right to kill ‒ for the sake of eating or for the sake of art), presented a performance entitled Fressen, involving a huge number of participants and a huge amount of seafood and kitchen equipment. It was an amazing experience of overcoming normative boundaries and mental walls, an unrestrained feast in time of the Covid plague (to be fair, the pandemic situation in Poland, thank goodness, has lately been relatively improving). I had an opportunity to speak with Katarzyna Kozyra separately; the interview will be published on this portal in near future, so I will not go into details right now, except for the fact that one of the key elements in this performance was smell ‒ the smell of fresh fish, prawns, octopuses and eventually the aromas of frying and poaching the seafood with the help of numerous pans and pots.

Exhibition ''Night Tele Visions'. Works by a duo of artists – Małgorzata Pawlak and Mikołaj Kowalski – at the m² gallery

In this sense, Fressen resonated for me with the exhibition entitled Night Tele Visions by a duo of artists – Małgorzata Pawlak and Mikołaj Kowalski – at the m² gallery. Quite small yet two-storied, the gallery had lent its basement floor to a ghost forest ‒ painted, multiplied with mirrors and infused with the scent of pine-trees with the help of an extract prepared by the artists themselves. Alongside the paintings, the gallery space was scattered with tiny TV sets broadcasting nocturnal scenes that were transmitted to the screens not via ordinary video cables but with the help of antennae receiving the signal of a tiny suitcase-sized television station. This combination of analogue television with images of natural shapes worked perfectly, taking us to a space of conjecture, mist and pre-dawn haze. The artists say that they were inspired by their impressions from nocturnal walks in the city and its outskirts during the lockdown and their observations of urban wildlife.

Fragment of exposition at the Fundacja Profile

Work by Monika Falkus / gallery Szara

I viewed this exhibition on Friday night. The following morning saw Warsaw fabulously wrapped in thick fog; the city’s skyscrapers looked like the set of a sci-fi movie. However, soon enough the first rays of sunshine transformed this scene into a completely different story. Yes, Warsaw is an energetic, powerful and at the same time ‒ open and playful city. I looked at it from a 13th-floor room at Hotel NYX, from the 16th floor of a high-rise dating from the late Socialist era, from two bridges across the River Vistula and from the windows of multiple art galleries. I saw its trees, its people and the tables of its cafés. And the feeling that it is worth coming back to again and again never left me. Warsaw itself is the secret ingredient that makes any edition of WGW special. Including Edition #11.

Title image: Work by Xawery Wolski at gallery Leto