Warsaw Is Growing

‒ as is the number of art galleries taking part in the annual Warsaw Gallery Weekend

Every year at the time when September meets October, Warsaw brims with people and events. Recent weeks saw the extremely successful launch of the Hotel Warszawa Art Fair: held in mid-September, it showed art objects from 20 Warsaw galleries in assorted rooms and spaces at this hotel with a stormy and rich history. Erected in the 1930s, this 16-storey building, the tallest one in Poland at the time, was almost completely destroyed during the war, with only the steel carcass and some elements from the lower floors remaining intact. It was then rebuilt in the 1950s and served as a Warsaw landmark hotel between 1954 and 2002. It remained closed until late in 2018, when, thanks to its new owners, investments and reconstruction, it reclaimed its spot in the list of the most elegant hotels in Warsaw. The idea of holding an art fair in a hotel is not novel, to mention just the New York Gramercy International Art Fair of 1994; however, its Polish incarnation turned out to be a success and very much in demand: the first day’s event was for VIPs only, but on days two and three, when the door was open to everybody, there was a sizeable queue forming outside the entrance. In all, over the three days of Hotel Warszawa Art Fair’s run it gathered 3000 visitors and resulted in successful sales.

At the exhibition Baustelle by Zuzanna Czebatul at the Import Export Gallery. Zuzanna’s photographs are hung on guard railings used to fence off buildings under reconstruction. Interestingly, the building housing the gallery is indeed currently undergoing reconstruction and the gallery space is the only part of it that can be accessed. Photo: Bartosz Górka

Generally speaking, despite the endless warnings of crisis and inflation, interest in art collecting is on the rise in Poland, and prices are increasing ‒ particularly for paintings by young Polish artists, I was told by the well-known Warsaw collector Piotr Bazylko, who opened his own art gallery Import Export with his business partner a year ago. While his gallery was among the participants of the ‘hotel fair’, Bazylko believes that Polish collectors, especially those who belong to the so-called ‘new wave’, should now make the next step, namely, move toward increasing interest in the international scene. It would make sense then to invite some international galleries to next year’s event at Hotel Warszawa. In any case, it is obvious that the Polish art market is growing fast; many critics and gallerists are talking about a proper boom in this area; some are even afraid of a market overheat.

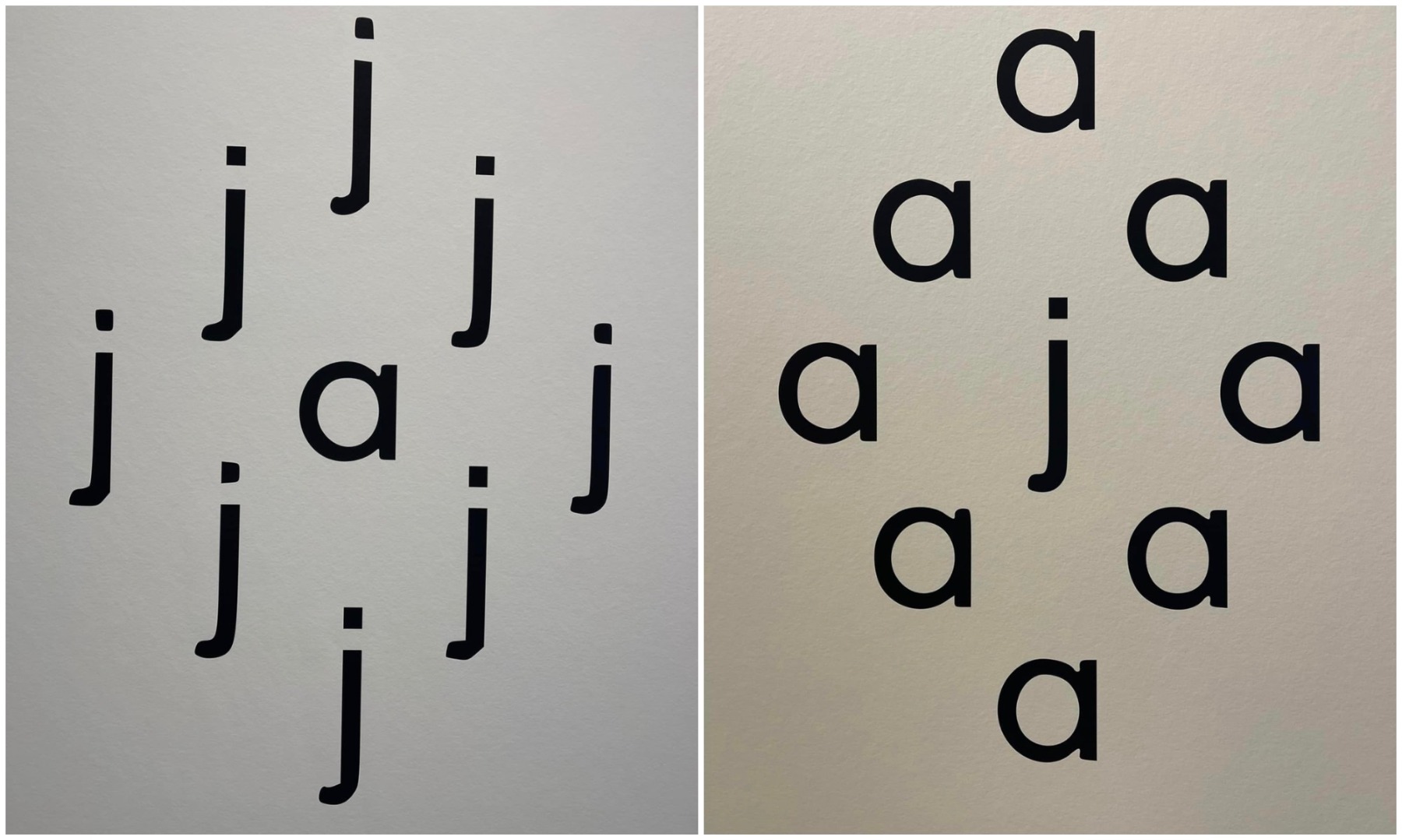

Stanisław Dróżdż. I, 1998. Fragment of the artist’s solo show at Esta Gallery

On 30 September, the Szum Magazine published a large survey on the subject; it features, among others, the following opinion expressed by the independent curator Kuba Szreder: ‘On the eastern outskirts of Western Europe galleries are still frequently run like informal collectives, enthusiast circles, family business or non-government organizations. Commercial motivation intertwines with socially engaged activity or attempts to build an art infrastructure and provide artists with resources of which, as we know, there is a shortage in Poland. It is hardly surprising that talented artists and curators are hungry for commercial success: a mirage of comfort trumps hopelessness of artistic poverty.’ Meanwhile, other respondents claim that what is taking place is not a boom of any kind at all; rather, it is a perfectly natural acceleration of development following a two-year period when growth was slowed down by the pandemic. Gunia Nowik from the Gunia Nowik Gallery, one of the co-founders of the Hotel Warszawa Art Fair, is among those advocating this view.

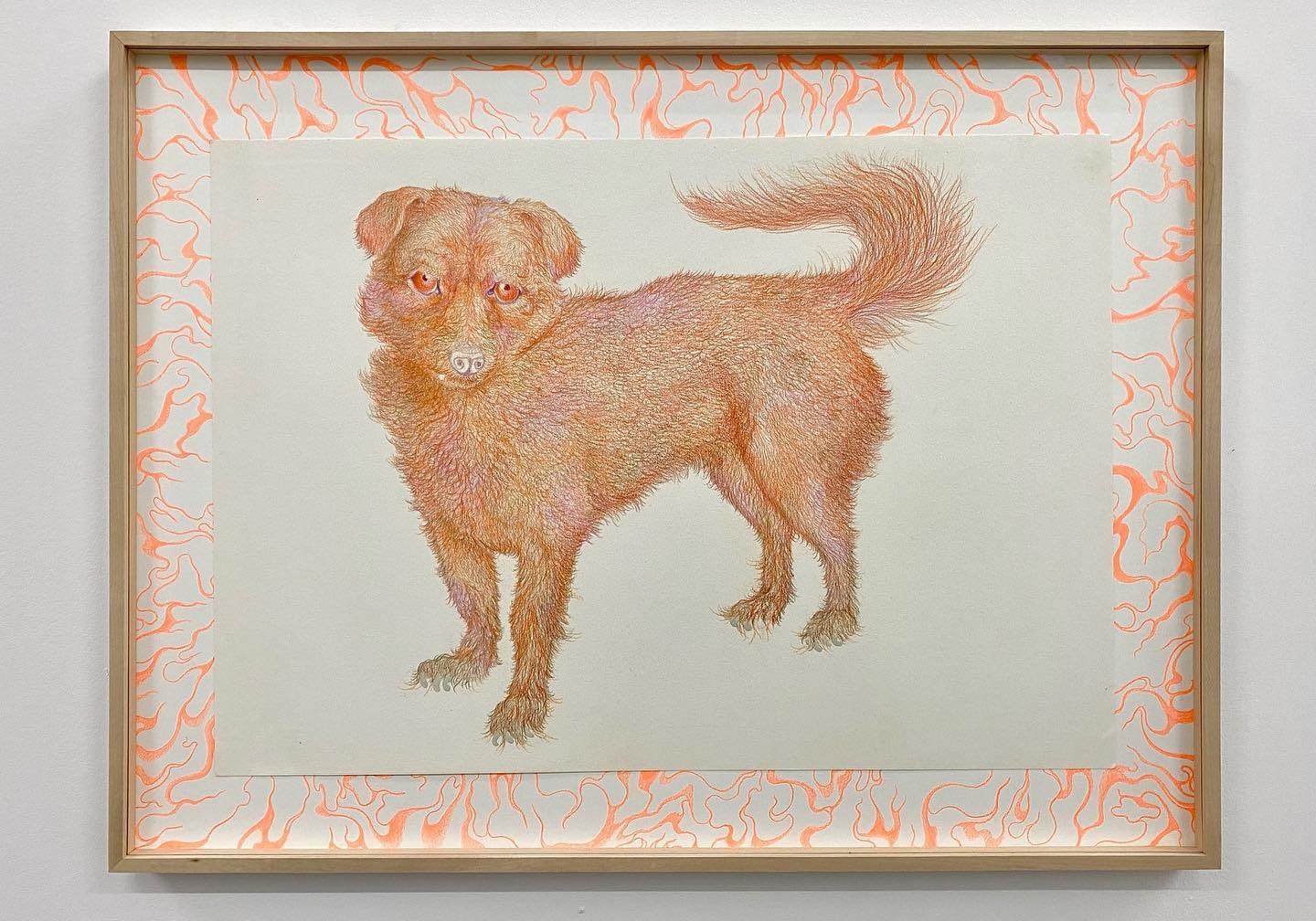

Masha Silchenko. Winged Vase, 2021. From the artist’s show at the Import Export Gallery

In any case, collectors are still very much focusing on local artists. Although there is, of course, interest in artists from Ukraine; for example, a show by the Paris-based Odessa-born artist Masha Silchenko just finished its run at the selfsame Import Export Gallery. In early September, a campaign called ‘Druh Druha’ took place in several Warsaw art galleries: six exhibitions representing artists from Ukraine opened at the time (while Import Export extended the run of Silchenko’s solo show). Although you don’t see Ukrainian flags everywhere you go in the city these days, it is very likely simply because help and support for Ukrainians has by now become a normal everyday thing. As I was told by Joanna Mytkowska, director of the Warsaw Museum of Modern Art, the population of the city grew by 17 % after 24 February 2022. And Warsaw is dealing quite well with the adaptation process of the newcomers: the sound of Ukrainian or Russian with a Ukrainian accent in the streets is now a familiar feature of daily life in the Polish capital.

In our last year’s review of art life in Poland we wrote about the increasing pressure on it by the right-wing political forces in power. The Polish Ministry of Culture replaced several directors of major art institutions; it happened, for instance, at the well-known Zamek Ujazdowski art centre, but the latest ‘reversal of polarity’ of this kind was performed at the Zachęta National Gallery of Art, an iconic Polish art museum, where Hanna Wróblewska, who had headed it since 2010, was fired from her post. It is this state-run art institution that holds project competitions for the Polish pavilion at the Venice Biennale and afterwards sees through the realization of the winning project. It means that the Polish representative at the next Venice Biennale will be selected by a panel espousing completely different political views. On the other hand, things may yet change quite radically: next autumn will see Poland elect a new parliament, and polls currently seem to indicate that the opposition to the ruling Law and Justice party is growing stronger. In any case, at a time when the state decreases its support for contemporary art, galleries and private initiative play an increasingly significant role in this regard.

A work by Tomasz Kręcicki at the Stereo Gallery

Therefore, let us get back to this year’s events in Warsaw. If Hotel Warszawa Art Fair showed ‘art as part of interior decor’, fitting it into spaces that are not directly intended for displaying works of art, a ‘parade of galleries’ in a much more familiar setting, their usual spaces, commenced in late September in keeping with an old annual tradition ‒ the 12th edition of the Warsaw Gallery Weekend (WGW). Opening on 29 September, it featured new exhibitions at 33 (!) Warsaw art galleries, all of them associated with the contemporary art scene with good reason (the city is also home to quite a number of art spaces that specialise in works of a more commercial and decorative nature).

A work by Arobal at his exhibition ‘Feelers’, Galeria Szydlowski

What seemed striking after visiting a large part of WGW shows was the predominance of the medium of painting ‒ a somewhat ‘outrageous’ type of painting and yet, in a way... a tiny bit too predictably outrageous. There were considerably fewer sculptures (although it was ‘a sculpture garden’ that the Raster Gallery presented in their yard) and fewer yet video works; in regard of the latter, the one that made a particular impact was the animated video projection on a semi-transparent curtain at Galeria Szydlowski ‒ a human figure changing its outlines like a magnificently blossoming plant in fast motion. It was part of the exhibition by artist and illustrator

Bartek Kociemba who goes by the alias Arobal; the show, however, again was dominated by drawings ‒ masterfully done and amusing. ‘In the exhibition animal, floral and erotic motives are presented in a form of installation, where drawings are not individual phenomena but the roles played to visualize his art philosophy, where visible and invisible are equal,’ it says on the website of the gallery.

In an attempt to stir up interest in video as an art medium, WGW had put together a special video art programme shown at Kino Amondo; furthermore, this year’s Central European Art and Collector’s Summit, a panel discussion regularly held during WGW, was dedicated to collecting video works. After all, some fifteen years or so ago it was video art by the likes of Katarzyna Kozyra that used to shape the international reputation of Polish art.

Visitors in front of a work by Katarzyna Korzeniecka at Gunia Nowik Gallery. Photo: Bartosz Górka

Another significant constant in this year’s edition of WGW was interest in the subject of nature and in natural materials and approaches. The above-mentioned Gunia Nowik Gallery presented two shows, both interacting with this subject matter in various forms and formats. First, Katarzyna Korzeniecka, a Polish artist with Georgian roots working in the techniques of ebru (paper marbling) and marquetry, was represented with an exhibition entitled ‘Thea’, a reference to the protoplanet Thea (or Theia) that once collided with Earth (a product of this collision is a giant piece of debris known to us as the Moon). The alchemy of floating coloured inks in water onto which huge sheets of paper are then laid (that’s what ebru is), creating layers upon layers by repeating the procedure again and again (the paper is first left to dry and then submerged into water with a different colour), results in truly cosmic landscapes. Equally impressive are Korzeniecka’s cosmic-themed works created from tiny fragments of wood (the craft of inlay is the foundation of the technique of marquetry); moreover, these pieces belong to completely different types of trees from different countries and even continents. Yes, these are also ‘flat’ pieces fit for hanging on your wall, and yet there is some sort of natural power to them that elevates human modernism to a completely new meta-level ‒ a ‘theia-level’ perhaps.

Fragment of the exhibition by Nicolas Grospierre at the Museum of the Earth

The other project of this gallery was a show by the French-born photographer Nicolas Grospierre, who resides in Poland (we published an extensive interview with him back in 2016). He is interested in the structure and patterns of minerals ‒ agates, and he presented his exhibition ‘Lapis Mundi’ at the Warsaw Museum of the Earth. The question is, however, whether the real agates from the museum’s collection Nicolas had incorporated in his show are not more fascinating than his own masterful photo collages interpreting the visuality of the minerals ‒ a tough call.

Works by Norbert Delman at the Iluzjon Cinema. Photo: Olga Sivel

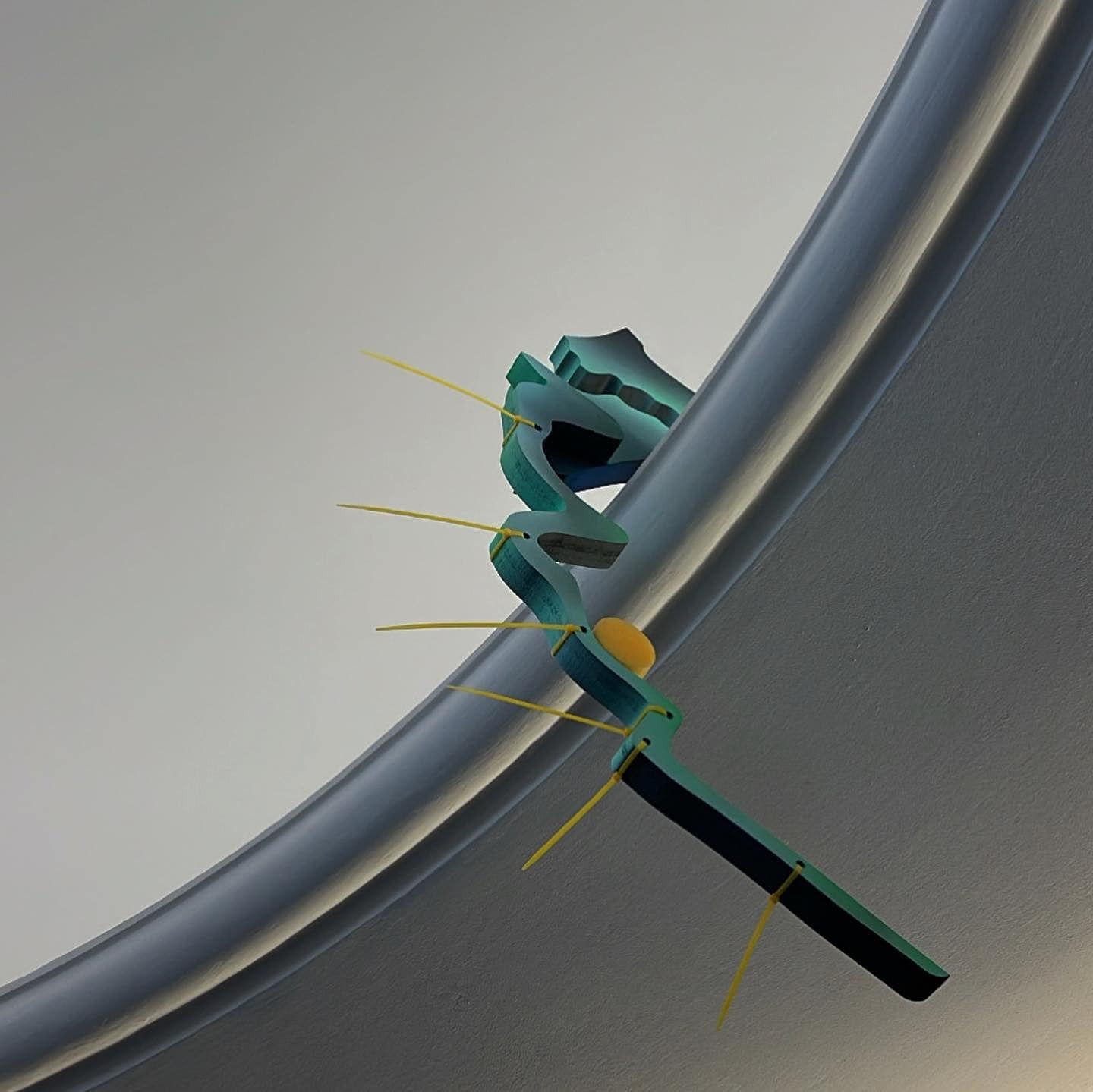

One of the creations by Norbert Delman has crawled up to the ceiling of the Iluzjon Cinema. Photo: Olga Sivel

A confident appearance was made by the Propaganda Gallery that has been constantly changing the venues for its projects in the recent years. The gallery had chosen the cosy rotunda of the Iluzjon Cinema for a show of works by the young Polish artist Norbert Delman, who uses painted sheets of MDF, plastic and plastic foam to develop some kind of life-affirming forms, not quite of this world, yet organic and unrestrainable. ‘They develop like plants doomed to grow in unfavourable conditions. Wanting the main stem, frail at the base, they rebound in lush lateral buds. They annex the surrounding space with their plastic vines.’

A fragment of exhibition Blind Spot by Ada Zielińska

Another project presented by Propaganda was the ‘Blind Spot’ exhibition by Ada Zielińska, who belongs to the thirty-somethings’ generation of Polish artists. This is how Ada describes her method: ‘In my works I am exploring the idea of destruction and documenting the catastrophe that surrounds me, confronting myself with material disintegration. This artistic practice serves me as a specific self-therapy, an attempt to control what is inevitably going to end. My fascination towards destruction constantly evolves.’ The artist is famous, for example, for her ‘Pyromaniac’s Manual Book’ series of photographs recording instances of car arson (the cars set on fire are not owned by other people, of course, and are parked in specially chosen places). No arson this time around; the show was housed in a small office/maintenance space on the first floor of a building opposite Zachęta. Visitors were greeted by a crash barrier, the kind usually lining highways at road bends (this one was placed on the floor, bent by a powerful blow) and a series of rear-view mirrors (19 of them) mounted on the walls and in the corners of the room. On each of the mirrors a sentence was engraved, contributed on Ada’s invitation by the English poet Sam Riviere: ‘Crossroads as destiny centres / Do not think about it / The night is going to end’ ‒ along these lines. Plus, a number of landscape photographs with distinctively crude materiality, covered in layers and layers of glue. I was told by the owner of the gallery Jacek Sosnowski that the project was an attempt to capture the moment when a sudden awareness of risk switches on a maximum state of ‘here and now’ inside us ‒ when we give up analysing with the help of lengthy constructions, when time stands still and the only thing we hear is the noise in our ears (there was a whole bunch of technical-purpose pipes right under the exhibition space ceiling, and they were indeed humming all the time).

Delegates’ Dance by Kamil I in the underground parking-place of Puro Hotel

Interestingly, a number of other projects that left an impression on me were also presented outside the white cubes of art galleries. For instance, the gallerist (very active on the Polish art scene ‒ owner of two galleries with names that translate respectively as Human Heart and Human Death) and artist (both galleries showed his own projects at WGW) who goes under the pseudonyms Kamil I and Kamil II presented one of his works in the underground parking-place of the Polish hotel Puro. (The laudable interest in contemporary art shown by Warsaw hotels is worthy of a special mention.) Under the name Kamil I he showed a Dance Macabre-style installation entitled ‘Delegate’s Dance’: a circle of people in suits with all kinds of badges (superpower flag pins etc.) on their lapels, dancing hand in hand with uniform shiny metal skeletons. It was quite interesting to view the object on what was the election day back in Latvia, while the hotel’s guests in their cars did their utmost to get in and out of the moderately-sized parking-place without hitting an object of this installation. ‘These are politicians forming a circle ‒ a circle that never changes. They focus on emotions, on inciting, not on actual problems and ways of solving them. Politics should be boring and deal with countless tiny solutions to huge problems,’ the author, Kamil I, told me.

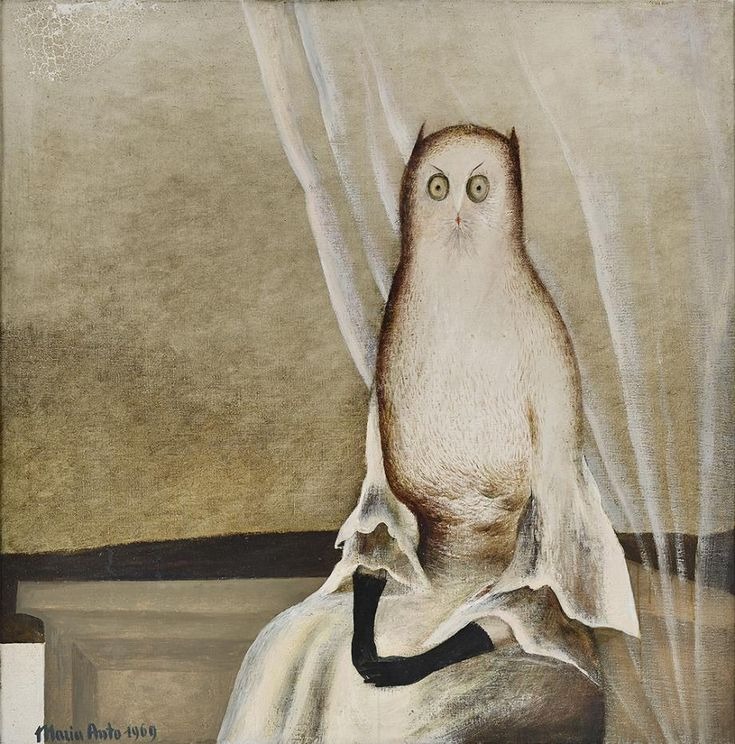

Maria Anto. ‘Owl’, 1969. Shown at the exhibition ‘The Owls Are Not What They Seem’

Another exhibition outside gallery walls was housed in the studio of the Polish artist Jan Możdżyński, and it was a tribute to the seminal Polish surrealist artist Maria Anto, mounted by the well-known Warsaw gallery Lokal_30. From the 1960s onwards, Maria Anto painted incredibly beautiful and mysterious owls; hence the reference in the title of the exhibition: ‘The Owls Are Not What They Seem’ ‒ a shout-out to the serial drama ‘Twin Peaks’, where this phrase was repeated on several occasions. One of the contributors was the daughter of Maria Anto, Zuzanna Janin; her installation consisting of authentic picture frames from Maria’s paintings (the museum holding these pictures decided to replace the frames with new ones and get rid of the old ones) is particularly good. The whole show was full of various incredible creatures, big and small, and of drawings, and the contributing artists (four of them) all have some type of connection with Maria Anto, either familial or purely circumstantial: for instance, somebody used to have their studio upstairs from the artist’s flat.

Object by Zuzanna Janin from the picture frames of Maria Anto’s paintings

While Jan Możdżyński’s studio was housing this exhibition, the host himself was taking part in a project entitled ‘Lovehammer’ at the Krupa Gallery with another young artist, Sebastian Sebulec. This pair of co-authors had decided to reimagine the popular ‘typically male’ pastime that is Warhammer, table-top battles between factions of a fictitious 41st-century universe with the help of miniature figures of warriors, monsters and military equipment. Curator of the exhibition Antoni Burzyński believes that ‘the artists use motifs and tropes characterising this type of entertainment, as well as inspiration from manga, fantasy and legends, to queer violence-based attitudes and turn the mechanics of battle into a love idiom’. To this end, they have created their own personal mini-universe, a game where the figures of the characters build relationships that are radically different from the ones in the war game ‘original’. ‘As advocates of love and equality, feminists, but also fans of battle games, Sebulec and Możdżyński propose to change the stereotypical, antagonistic perspective into a relationship based on care, love and affection. They want to play, but on their own terms, reflecting what they themselves believe in.’

Installation Distillates by Karolina Grzywnowicz at Jednostka Gallery

The subject of care and re-examination of ‘familiar things’ is also explored in the project that won the prestigious special award of ING Polish Art Foundation (a special prize and the main prize are awarded at every edition of WGW). It was the aromatic ‘Distillates’ by Karolina Grzywnowicz, dedicated to anticolonial revision of post-imperial landscapes, shown as part of the ‘Grounding’ exhibition at Jednostka Gallery. Grzywnowicz here focuses on scents, which, as we know, are the most permanent conveyers, transmitters of memory and experience. According to recent studies, scents not only trigger immediate flashbacks of traumatic experiences in people suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder but can also be used as a key element in therapy, helping develop mental resilience.

Karolina Grzywnowicz speaks about her project Distillates at Jednostka Gallery. Photo: Bartosz Górka

‘Landscape has long become an instrument of ideology and power,’ Paweł Mościcki wrote in his essay ‘Scents of Resistance’ dedicated to the exhibition, ‘or, to be more precise, a means of projecting and realizing imperial imagination. Each act of colonial appropriation robbed the conquered nations not only of their political and cultural independence but also their sensual experience, subjecting it to the diktat of the colonialists. The imperial robbery was not limited to natural resources, useful for the production and consumption of goods, but also included the objects and ways of seeing, hearing or sensing. [..] It was the ultimate theft of a whole world. [..] The intersection of the political and the intimate is the strongest in the domain of the senses, particularly the sense of smell, around which the project is centred. [..] That inspired Grzywnowicz to produce healing aromatic oils from plants used by the oppressors to cover their crimes. [..] This will help you remember that this violence should have been washed away and uprooted.’

Karol Radziszewski. Harnasie, 2022. From the exhibition ‘Myths’ at BWA Warszawa Gallery

The exhibition winning this year’s main prize awarded by ING Polish Art Foundation was Karol Radziszewski’s ‘Myths’, an interpretation of the subject of the historical narrative and its myths in a series of works dedicated to the artistic world and personal circumstances of the composer Karol Szymanowski, one of the most prominent Polish composers of the 20th century. Founded in 2011 and a regular contributor to WGW, the BWA Warszawa Gallery has posted this comment by the curator Michał Grzegorzek: ‘The artist reflects on the ways of discussing queer figures without reductive admiration. On the place of queer desire in normative stories. On the approaches to writing the myth of the past without a detriment to the future.’ It is truly impressive painting that explores the actual medium with genuine energy and vitality.

A work by Olga Dmowska at the Pola Magnetyczne Gallery exhibition. Photo: Bartosz Górka

Another significant feature of WGW is the conspicuous presence of art galleries opened in Poland by gallerists from other countries. This year, there were already three of them. The first one was a gallery with a solid reputation and well-known name, Pola Magnetyczne, run for many years now by a Frenchman with Polish roots Patryk Komorowski, who has relocated to Warsaw. They showed a very successful joint project by two artists, a French and a Polish one ‒ Cécile Bouffard and Olga Dmowska. The second example we should mention is the Rodríguez Gallery; founded in 2015 in Poznań by a Spaniard named Carlos Rodríguez, the gallery has been bringing its shows to the capital during WGW since 2019. Rodríguez showed the exquisite conceptual sculptures by Marlena Kudlicka.

A work by Marlena Kudlicka at the Rodríguez Gallery

The third art gallery joining the WGW programme this year was Bacalarte, opened recently by the Mexican-born Roberto Andrade. As its fifth exhibition since opening, the gallery presented a project entitled ‘WHIP’ ‒ an acronym for ‘women who are hot, intelligent and in their prime’. It is a show by two artists, Agata Zbylut and Iwona Demko, who both, according to the curator of the project Ines R. Artola, ‘perfectly fit into this category. Both born in ’74, with academic experience and over twenty years as artists, much of which has been used to explore and deepen feminist issues.’

Works by Agata Zbylut from the Power of Love series at Bacalarte Gallery

Object Clitoris of the Great Goddess by Iwona Demko at Bacalarte Gallery

It was from this gallery, located at the bottom edge of the WGW map, that I started my this year’s journey through art spaces and art worlds of Warsaw. It was exciting, edifying and diverse; I walked almost 50 thousand steps, made four trips on BOLT and saw a lot of things I feel keen to share. WGW is still a perfect opportunity to get to know the Polish art scene while also exploring Warsaw itself ‒ a growing city just starting to make an impact on the European art map. This is by far not the last we will hear about Warsaw.

Title image: Visitors in front of the entrance to Leto Gallery. Photo: Bartosz Górka