Roaming through worlds and playing games

Impressions from the exhibition WORLDBUILDING: Gaming and Art in the Digital Age, a milestone project of the JULIA STOSCHEK COLLECTION, which concludes on February 4th.

To be honest, I've always been somewhat critical of the gaming industry and games in general as a form of entertainment and exploration. I remember back in the mid-2000s when I was working part-time at an advertising agency, I was constantly amazed at how my colleagues closed their work files at six o’clock on Friday evenings and the whole team began to eagerly "battle" each other online. At that moment, I wanted to stay away as far as possible from computers. Perhaps I'm still a person shaped by the pre-gaming era of books and etcetera. In any case, games are a reality for a social group of several billion people (almost three billion interacted with them in some way in 2021). And this is the sphere that contemporary artists are closely observing—both as a format and as a theme.

While I may not be much of a gamer myself, I do have experience mimicking the gaming format. In 2005, along with animator Edmunds Jansons and programmer Janis Muižnieks, we created the game "I'm Text" which was essentially a shooter where you had to shoot with letters, and with success, the player would receive a poetic text line by line—a sort of attempt to create a "universal poem". The text could shoot back (with office buttons), and if hit, you would lose the last line. This game now only survives in exe format, and Google perceives it as a virus in my email. But the maze game, invented by New York-based artist Victor Timofeev, can be played right now at his Riga exhibition at Gallery 427—it's a virtual version of the gallery space itself, which you have to navigate while some mysterious entities hinder you. You sit in the gallery and play a game in which you move through the gallery as if it were a parallel space, a world that "mirrors" reality but presents it differently, as a setting.

Installation view, WORLDBUILDING, JSF Düsseldorf. Photo: Simon Vogel, Cologne

And that's probably the main feature of games—the ability for interactive engagement with a narrative that fundamentally differs from your life, even if it uses some of its motifs. It's worldbuilding as an industry. And it's precisely this word that stands first in the title of the huge exhibition that concludes this weekend in Dusseldorf after a year and a half of display. WORLDBUILDING: Gaming and Art in the Digital Age — curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist, marks the 15th anniversary of the JULIA STOSCHEK COLLECTION.

In 2014, works from this collection were also exhibited in Riga at the High Performance exhibition at Riga Art Space. This collection is primarily focused on preserving the most interesting works of new media and time-based art. It includes about a thousand pieces of art created starting from the 1960s. For 15 years, the collection has had its own home—a large building in Dusseldorf (the Julia Stoschek Foundation also has an exhibition space in Berlin).

Gabriel Massan, THIRD WORLD: THE BOTTOM DIMENSION, 2022–ongoing, 4K video, color, no sound, loop; video game, infinite duration, color, no sound. Installation view, WORLDBUILDING, JSF Düsseldorf. Photo: Simon Vogel, Cologne

When Hans Ulrich Obrist was offered to conduct an "anniversary project" with works from the collection, he chose a theme that seemed most promising to him: "In the digital age, video games have become one of the most important cultural forms of our time, shaping not only our leisure time but also our sense of identity and community. This exhibition brings together a wide range of artists, especially young, relatively unknown artists who are exploring the creative possibilities of gaming”. The exhibition became a true research field for Obrist, with the composition of the presented works constantly changing and evolving. In fact, a parallel exhibition under the same title, but with a different selection of works, opened last summer in France at the Pompidou-Metz.

"Traditionally, video games were created by a small and insular group of people coming from the world of engineering, who produced games with a very limited perspective. This is now changing rapidly, with many more people having access to the tools for making games. Artists are increasingly developing the technical ability to invent, design, and distribute their own games on all continents to create virtual worlds of diversity and inclusion, contributing strongly to a plurality of voices and different perspectives," writes Obrist in his curatorial introduction.

Installation view, WORLDBUILDING, JSC Düsseldorf. Photo: Simon Vogel, Cologne

The exhibition is spread across two floors of the building, with glass partitions and doors between halls and rooms reflecting and multiplying monitors and projections. This creates a sense of permeability for all of these worlds. They are indeed very different—from a modest monitor and an Atari game console on which an art-hacker version of Space Invaders by American Cory Arcangel is reproduced, to a whole room with interactive projection, additional screens, and an installation called She Keeps Me Damn Alive (2021) by Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley. Interestingly, both of these works reveal and modify the shooter-specific nature in different ways. In 2004, Arcangel came up with the idea of revealing the code of Space Invaders, a game created by Atari in the late 1970s. When he came up with this, both the console and the game were essentially a thing of the past. The essence of the game was to fight with space invaders attacking you; Arcangel removed all the invaders except one— the one that inherited the entire arsenal and all the abilities of its fallen comrades. It became impossible to defeat him. A game in which winning is impossible loses its meaning, and the player sooner or later "lays down their arms".

Cory Arcangel, Space Invader, 2004, video game, infinite duration, color, sound, hacked Space Invader Cartridge, Atari 2600 video game system, artist software (coded by Alexander Galloway), dimension variable. Installation view, WORLDBUILDING, JSF Düsseldorf. Photo: Simon Vogel, Cologne

In part, this resonates with the meanings of Brathwaite-Shirley's work—here, you can physically pick up a golden gun. It is from this gun that you begin to shoot at mysterious dark objects and figures in the space of a huge three-meter projection in front of you—in this game, you defend Black Trans people against white supremacy's spirit. But no matter how desperately and accurately you shoot, in the end, a message appears stating that you were not good enough, your wards suffered because of you, and you must leave the game. This work seems to push you to constantly question your actions. How much do you control your golden gun, and how much does your golden gun control you? "The game uses the interactions of those who play it to recenter their understanding of responsibility; challenging them to see if their sense of when to act and when not to act is sustainable for black trans people".

Theo Triantafyllidis, Pastoral, 2019, video game, infinite duration, color, sound. Installation view, WORLDBUILDING, JSF Düsseldorf. Photo: Alwin Lay

In primitive gamer terminology, games are divided into shooters and exploration or adventure games—and there are plenty of the latter, including those using VR. One of the most appealing is Theo Triantafyllidis' game and installation Pastoral (2019). Seated on real pieces of compressed straw and using a game controller, players control the body of the central character, a hyper-bodied, hybrid-gendered Orc character wearing a bikini. In most games and social media terminology, orcs are monstrous and aggressive enemies whom users of World of Warcraft, for example, fight against. "But Triantafyllidis’s Orc is nearly nude, brushing its way through the rustling waist-high hayfield in a bikini, positioned to explore and search the bucolic and bountiful field," writes Mary Flanagan in the exhibition catalog.

Ian Cheng, BOB (Bag of Beliefs), 2018–2019, artificial lifeform, infinite duration, color, sound, dimensions variable. Installation view, WORLDBUILDING, JSF Düsseldorf. Photo: Alwin Lay

Can we be an orc in a bikini in an endless deserted field of rye in our real lives? Hardly. The curatorial introduction to the exhibition quotes C. Thi Nguyen's book Games: Agency as Art, in which he writes that games, particularly video games, are a distinct type of art that "let us experience forms of agency we might not have discovered on our own". For example, becoming the owners and caretakers of a digital entity named "BOB (Bag of Beliefs)" by artist Ian Cheng—a fire-red, hydra-headed, cactus-like thing. This creature moves around its digital home, interacting with objects that come its way as it tries to understand its own needs and how to fulfill them. BOB is close to what cybernetics calls "autopoietic", meaning self-reproducing. With its snake-like body constantly changing and branching, BOB navigates through the flow of impulses and surprises that life offers, attempting to adapt. "Yes, BOB is a piece of software, a real-time simulated lifeform displayed in a gallery like a twenty-first-century zoo animal—subject to our harassment, indifferent to our love," writes Travis Diehl about this piece. Visitors can download an app allowing them to feed BOB from anywhere in the world or... throw bombs at it, which, upon exploding, once again scatters BOB into pieces.

Ian Cheng, BOB (Bag of Beliefs), 2018–2019, artificial lifeform, infinite duration, color, sound, dimensions variable. Video still. Courtesy of the artist, Gladstone Gallery, New York/Brussels/Seoul/Los Angeles and Pilar Corrias, London.

In general, there are numerous opportunities to enter and explore various realms here with VR helmets of different shapes and models, on monitors using controllers, and in the gamefilm space—an interesting development based on the art group Keiken's concept. The Life Game (2021) is an interactive film series. "The film follows ME, a protagonist who finds themselves lost, lonely, and surrounded by self-centered technologies. The series unravels their whirlwind relationship with their digital twin MI, as they fall deep into a boundless Metaverse." Here, the heroine is plagued by numerous unresolved issues, and the player-viewer can't really help her in any special way, just "counting" her problems with the cursor and moving on to the next level or scene.

Keiken, PLAYER OF COSMIC REALMS, 2022, interactive installation, infinite duration, color, sound, dimensions variable. Consisting of: Keiken, The Life Game, 2021, multiscreen game, infinite duration, color, sound; Keiken, Bet(a) Bodies, 2021–2022, wearable haptic womb, digital audio, 9′12″, sound, silicone, LED light, mini computer, haptics, amp. Installation view, WORLDBUILDING, JSF Düsseldorf. Photo: Alwin Lay, Cologne

In another Keiken work also presented to visitors at the exhibition in Dusseldorf, "the audience is invited to put on the wearable haptic womb. Once they plug in the headphones and womb, visitors can experience the sound, frequencies, and vibrations of different animals that all communicate through ultrasound. These animals are bats, dolphins, whales, tarsiers, moths, frogs, rats, katydids, and oil birds." In other words, we are invited to feel something, to experience something, to connect with some new part of ourselves.

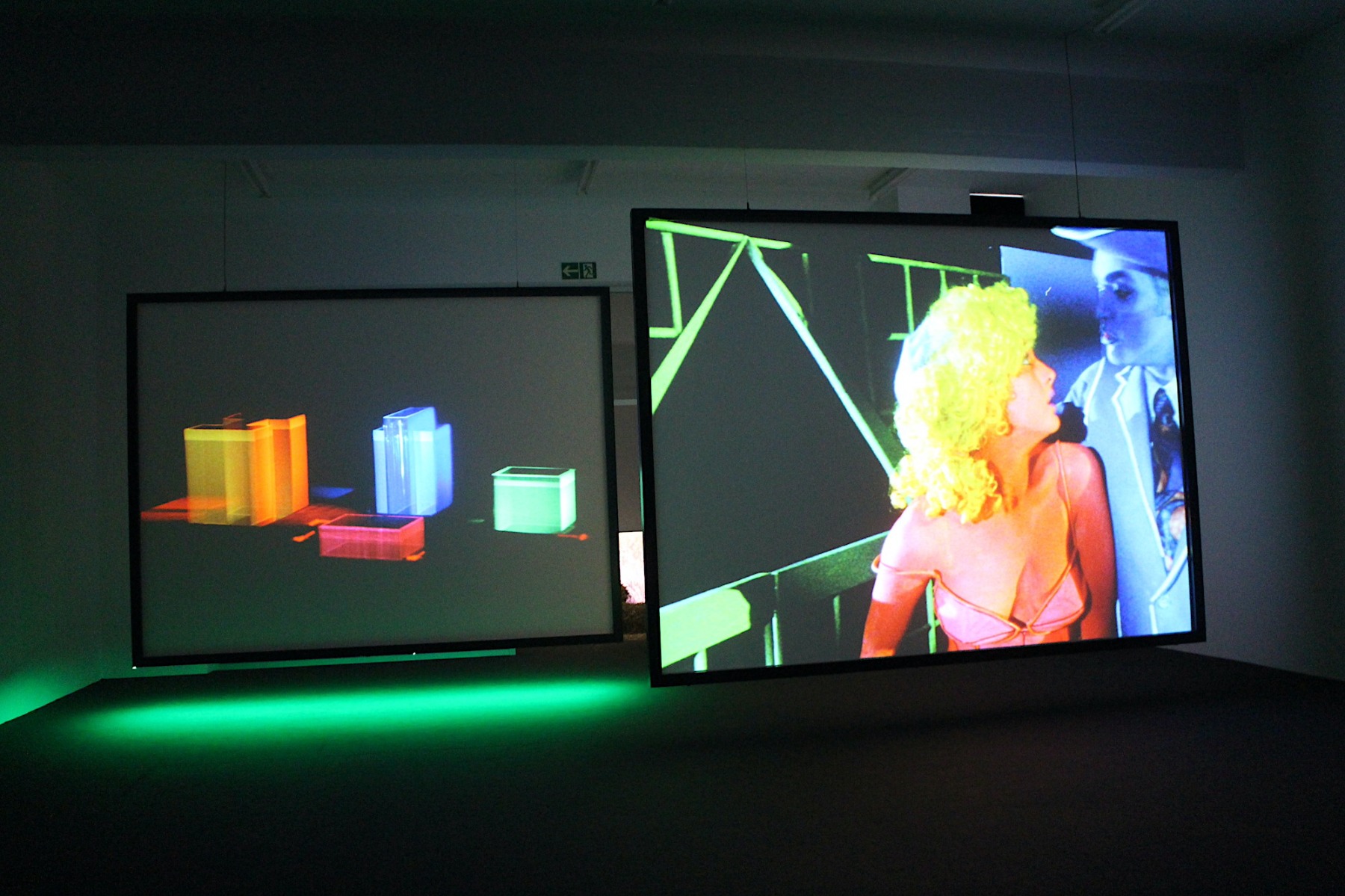

To what extent do such journeys enrich us? Probably as much as we are open to new experiences and as much as we are interested in "other dimensions". But there is always a question – what are we willing to go through to play such games? In this sense, one of the most memorable works to me was not a game at all but a two-channel film installation by Ericka Beckman titled Hiatus (1999/2015), which unfolds the scenario of just such a virtual journey. The entire aesthetics of the event are infused with 90s cyber fantasies, allowing us to view it as a wonderful example of retro-futurism mixed with surrealist cinematic techniques.

Ericka Beckman, Hiatus, 1999/2015, two-channel film installation, 16mm film transferred to HD video, 22′, color, sound. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Sergej Timofejev

"When cyber-punk protagonist Wanda loads a floppy disk onto her computer and slips into a wired-up black suit, she transports herself into virtual space where the game is on. We see the setting change from her office to a Tetris-like black box; we see her growing 'programs' by tilling a garden… until an electrical storm threatens her crop and power supply, bringing with it Wang—'Player 33, from Houston'—who lays claim to her land. In the film Hiatus, the virtual reality game world serves as a perfect playing field where Beckman pits the 'user,' instinctive Wanda, against another player, the militaristic Wang." At one point, Wang even commits real harassment against the main character and doesn't take her seriously at all. Charming and extremely brave, Wanda finally gets the opportunity to take revenge after long searches through very strange places turn Wang into a computerized fish. Happy and satisfied, she returns home. "This optimism provides a striking contrast to our contemporary situation, where corporate interests threaten not only virtual space but dream space too." This work emanates a sense of incredible freshness, the freshness of the 90s and the belief in a happy ending to the game. Modern artistic developments on gaming themes are not so optimistic; at best, they are ambient and dreamy.

It's amusing how comprehensive the exhibition is, even including a parody of itself. At least, that was my first impression from the video recording on one of the monitors. A strange but endearing creature rushes into the art space with equally strange but adorable works and then dashes out of it. Then the action repeats. The story behind this is that for his first major solo exhibition in London, NEW FICTION, KAWS (which is how the world knows New York-born artist Brian Donnelly, b. 1974) presented new and recent works in both physical and augmented reality at the Serpentine Galleries from January 18 to February 27, 2022. A virtual recreation of the show was simultaneously launched in Fortnite (an online video game and game platform), allowing millions of players from all over the world to experience the exhibition from anywhere in a completely new way. This virtual sprint through the Serpentine is spinning on the screen at the WORLDBUILDING: Gaming and Art in the Digital Age exhibition. At that moment in 2022, everyone interested could attend the art exhibition through the game, and in the open art exhibition in Dusseldorf that has been running for a year and a half, we can also experience a multitude of games and worlds.

Lawrence Lek, Nepenthe Zone, 2022, open world video game, infinite duration, color, sound. Installation view, WORLDBUILDING, JSF Düsseldorf. Photo: Alwin Lay, Cologne

The introductory text to WORLDBUILDING, written by Hans Ulrich Obrist, concludes with the following: "The artists enable us to become immersed in a multitude of alternative realities spanning past, present, and future, and questioning the very nature of reality. As Philip K. Dick once said, 'Reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away’." And much like a good movie, this exhibition changes reality itself. When you step out of the Julia Stoschek Foundation building and back into the city, you can’t help but marvel at how well the graphics are drawn in this picture you see before you while you unconsciously try to guess what kind of gameplay is surrounding you now.

Title image: LaTurbo Avedon, Permanent Sunset, 2020–ongoing, video, 6′13″, color, sound. Video still. Courtesy of the artist